Published online Jul 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3892

Revised: April 1, 2007

Accepted: April 4, 2007

Published online: July 28, 2007

Enteroenteric intussusception is a condition in which full-thickness bowel wall becomes telescoped into the lumen of distal bowel. In adults, there is usually an abnormality acting as a lead point, usually a Meckels' diverticulum, a hamartoma or a tumour. Duodeno-duodenal intussusception is exceptionally rare because the retroperitoneal situation fixes the duodenal wall. The aim of this report is to describe the first published case of this condition. A patient with duodeno-duodenal intussusception secondary to an ampullary lesion is reported. A 66 year-old lady presented with intermittent abdominal pain, weight loss and anaemia. Ultrasound scanning showed dilated bile and pancreatic ducts. CT scanning revealed intussusception involving the full-thickness duodenal wall. The lead point was an ampullary villous adenoma. Congenital partial (type II) malrotation was found at operation and this abnormality permitted excessive mobility of the duodenal wall such that intussusception was possible. This condition can be diagnosed using enhanced CT. Intussusception can be complicated by bowel obstruction, ischaemia or bleeding, and therefore the underlying cause should be treated as soon as possible.

- Citation: Gardner-Thorpe J, Hardwick R, Carroll N, Gibbs P, Jamieson N, Praseedom R. Adult duodenal intussusception associated with congenital malrotation. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(28): 3892-3894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i28/3892.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3892

Intussusception is a condition in which the full-thickness of the bowel wall is telescoped into distal bowel. In the adult population, small bowel intussusception is uncommon. The lead point is usually a Meckel’s diverticulum, a hamartoma or a benign or malignant tumour[1]. The duodenum assumes a fixed, retroperitoneal position during embryological intestinal rotation and intussusception of this organ into itself is therefore usually impossible[2]. Gastro-duodenal and distal-duodeno-jejunal intussusceptions have been reported but are rare[3-6]. Prolapse of ampullary lesions through the duodenum into the jejunum has also been reported[2,5]. The case described here was a true duodeno-duodenal intussusception which was only possible because of a partial congenital malrotation.

A 66 year-old lady presented with a one-year history of intermittent epigastric pain, weight loss, itching and lethargy. She had iron deficiency anaemia (Hb 9.8 g/dL, ferritin 7 μg/L). Her liver function tests (LFTs) were abnormal with an obstructive picture (bilirubin 9 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 950 U/L, ALT 134 U/L, albumin 29 g/L). Her past medical history included nephritis (aged 9), asthma (aged 43), pneumonia (aged 55), multiple admissions for chest infections, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (aged 61) and bronchiectasis (aged 63). She was taking omeprazole (20 mg) and inhaled ipratopium, salbutamol and beclomethasone.

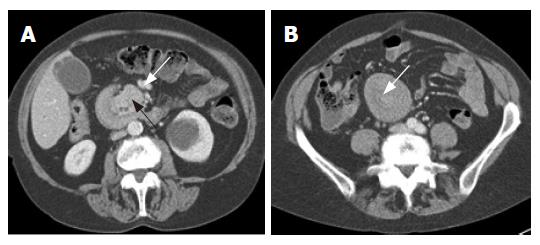

Abdominal ultrasonography showed intra- and extra-hepatic bile duct dilatation. Abdominal CT showed features of intussusception of the duodenum (“target sign”) and allowed identification of a large ampullary mass as the lead point (Figure 1A and B). Full-thickness duodenal wall intussusception was demonstrated by the low attenuation fat plane between the bowel walls[7]. The ampullary mass (black arrowhead) invaginated the duodenum. The common bile duct and main pancreatic duct were dilated. The superior mesenteric vein (Figure 1, white arrow) was anterior to the superior mesenteric artery at this level. Malrotation of the bowel was suggested by the position of the jejunal loops. The main pancreatic duct was dilated (6 mm) and the common bile duct measured 12 mm at its maximal diameter. The curvilinear areas of low attenuation between the bowel walls represent the fat outside the duodenal muscle wall (Figure 2, arrow). This is a key feature to distinguish intussusception from mucosal prolapse into distal bowel.

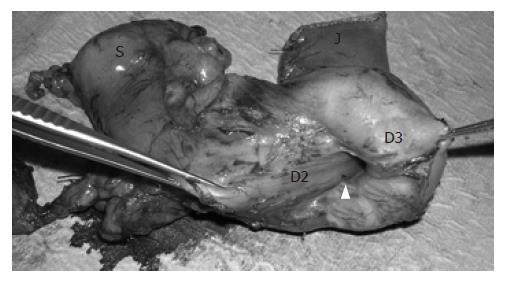

The mass was endoscopically biopsied and the histology was typical of adenoma. At laparotomy, the findings were of duodenoduodenal intussusception (Figure 2). The duodenal C-loop was abnormally configured and the duodenum course was entirely to the right of the superior mesenteric vessels. There was aplasia of the uncinate process. The duodenojejunal flexure was located on the right side of the midline. The cecum was normally positioned and there were no Ladd’s bands. The ileal mesentery was of normal length and fixation.

A pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure) was carried out (Figure 3). There were no significant vascular anomalies. She recovered without complications. Histology confirmed a 9 cm × 6 cm × 3 cm ampullary villous adenoma with foci of severe dysplasia but no malignancy. There was mild chronic pancreatitis of the pancreatic head.

The spectrum of congenital rotational abnormalities of the intestine includes non-rotation (typeI), duodenal malrotation (type II) and combined malrotation of the duodenum and cecum (type III)[8]. The abnormality in our case, classified as type II, is thought to result from arrest of rotation of the duodenal loop around the superior mesenteric vessels during return of the intestine into the abdomen in the tenth week of development[9]. The incidence of this abnormality in the general population is unknown, but many cases presenting late in life have had vague long-standing abdominal symptoms. It is unknown whether the reflux symptoms our patient experienced preceding identification of the ampullary mass may have been caused by the malrotation.

Congenital malrotation is often associated with abnormalities of fixation of the ileocecal mesentery, which can predispose to ileocolic intussusception. In one report, 40% of children with this type of intussusception had evidence of malrotation[10]. The case reported here was analogous in this respect because the duodenal loop was not completely fixed by peritoneum nor by the tunnel under the superior mesenteric vessels. The coincidence of the ampullary tumour and pre-existing duodenal malrotation was necessary to result in this full-thickness duodeno-duodenal intussusception.

There are several case reports in the literature that described tumours of the ampulla that were drawn through the duodenum into the jejunum. The tumours took with them the mucosal layer of the duodenum[2,5] and the resulting multilayered appearance on imaging can be difficult to distinguish from intussusception. This differential diagnosis is important because intussusception may carry a higher risk of complications of ischemic bowel, intraluminal bleeding and bowel obstruction compared to mucosal prolapse. Our case had obstruction to the bile and pancreatic ducts that caused abnormalities of the LFTs and chronic pancreatitis. This may have been caused by intermittent compression of these structures between the intussuscepting layers of bowel wall or by the mass effect of the ampullary tumour. For all these reasons, the presentation may be more acute and surgery may be considered more urgent if intussusception has occurred. Chalmers et al[2] have emphasized the value of visualization of a fat plane between bowel walls to diagnose intussusception. We suggest that intussusception should also be specifically considered if there is evidence of duodenal malrotations such as an abnormally configured C-loop or location of the duodeno-jejunal flexure to the right of the spine.

Duodeno-duodenal intussusception can occur if there is a malrotational abnormality of the duodenum and there is an ampullary lesion to act as the lead point. Intussusception is rare, but urgent surgery should be considered in this situation because of the risks of bowel infarction and obstruction.

S- Editor Zhu LH L-Editor Wang XL E- Editor Wang HF

| 1. | Meshikhes AW, Al-Momen SA, Al Talaq FT, Al-Jaroof AH. Adult intussusception caused by a lipoma in the small bowel: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35:161-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chalmers N, De Beaux AC, Garden OJ. Case report: prolapse of an ampullary tumour beyond the duodeno-jejunal flexure. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:141-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | White PG, Adams H, Sue-Ling HM, Webster DJ. Case report: gastroduodenal intussusception--an unusual cause of pancreatitis. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:357-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Uggowitzer M, Kugler C, Aschauer M, Hausegger K, Mischinger H, Klimpfinger M. Duodenojejunal intussusception with biliary obstruction and atrophy of the pancreas. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:240-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taams J, Huizinga WK, Somers SR. The wandering ampulla--duodenal-jejunal intussusception of a carcinoid tumour with displacement of the bile duct to the left iliac fossa. A case report. S Afr J Surg. 1992;30:153-155. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hwang CS, Chu CC, Chen KC, Chen A. Duodenojejunal intussusception secondary to hamartomatous polyps of duodenum surrounding the ampulla of Vater. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1073-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Merine D, Fishman EK, Jones B, Siegelman SS. Enteroenteric intussusception: CT findings in nine patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:1129-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stringer DA. Pediatric Gastrointestinal Imaging. Philadelphia: B.C. Decker, Inc 1989; 235-239. |

| 9. | Janik JS, Ein SH. Normal intestinal rotation with non-fixation: a cause of chronic abdominal pain. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:670-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brereton RJ, Taylor B, Hall CM. Intussusception and intestinal malrotation in infants: Waugh's syndrome. Br J Surg. 1986;73:55-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |