Published online Jul 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3855

Revised: April 23, 2007

Accepted: April 23, 2007

Published online: July 28, 2007

AIM: To clarify the relationship between the change of serum amylase level and post-ERCP pancreatitis.

METHODS: Between January 1999 and December 2002, 1291 ERCP-related procedures were performed. Serum amylase concentrations were measured before the procedure and 3, 6, and 24 h afterward. The frequency and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis and the relationship between these phenomena and the change in amylase level were estimated.

RESULTS: Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 47 patients (3.6%). Pancreatitis occurred in 1% of patients with normal amylase levels 3 h after ERCP, and in 1%, 5%, 20%, 31% and 39% of patients with amylase levels elevated 1-2 times, 2-3 times, 3-5 times, 5-10 times and over 10 times the upper normal limit at 3 h after ERCP, respectively (level < 2 times vs≥ 2 times, P < 0.001). Of the 143 patients with levels higher than the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by elevation at 6 h, pancreatitis occurred in 26%. In contrast, pancreatitis occurred in 9% of 45 patients with a level higher than two times the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by a decrease at 6 h (26% vs 9%, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Post-ERCP pancreatitis is frequently associated with an increase in serum amylase level greater than twice the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP with an elevation at 6 h. A decrease in amylase level at 6 h after ERCP suggests the unlikelihood of development of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

- Citation: Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Obana T. Relationship between post-ERCP pancreatitis and the change of serum amylase level after the procedure. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(28): 3855-3860

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i28/3855.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3855

Pancreatitis remains a major complication after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with a prevalence of 2%-9%[1-4]. Young age, female gender, difficulty in bile duct cannulation, pancreatic sphincterotomy, and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction have been found to be risk factors[1-3]. Although pancreatic stent placement and drug administration have been reported as being useful in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis, it is difficult to completely prevent this particular complication[5-16]. Serum amylase and lipase levels are regarded as useful markers for early diagnosis of pancreatitis[17-21]. However, detailed description of the change in serum amylase level after ERCP is lacking. Furthermore, the possibility of predicting the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis based on the pattern of change in serum amylase level has not been well clarified.

Patients who underwent ERCP-related procedures in Sendai City Medical Center, Japan between January 1999 and December 2002 were included in this study. Those who had previously undergone endoscopic sphincterotomy, papillary balloon dilatation or who had hyperamylasemia were excluded from the final analysis. After obtaining written informed consent, serum amylase concentrations were measured before the procedure and 3, 6, and 24 h afterward using a colorimetry method (H7250: Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan) or a dry chemistry method (Ortho VITROS 250: Johnson & Johnson Ltd., NY, USA). The reference range for the amylase was 54-168 IU/L. Clinical evaluations of symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, etc.) and physical finding (abdominal tenderness) were performed. The frequency and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis and the relationship between these phenomena and the change in serum amylase level were prospectively estimated. Pancreatic pain was defined as epigastric or back pain newly developed after the procedure. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sendai City Medical Center.

ERCP-related procedures were carried out in a standard fashion by using a side-viewing duodenoscope (JF200, 230, 240, TJF 200: Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Additional procedures, such as intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS), cytology of bile/pancreatic juice, transpapillary biopsy of the bile duct/pancreatic duct, endoscopic sphincterotomy, papillary balloon dilatation, pancreatic sphincterotomy and biliary duct stenting, were performed as necessary. An IDUS probe (XUM-G20-29R: Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) or a balloon catheter was inserted with guidewire assistance without sphincterotomy. All procedures were performed by operators with experience in more than 1000 cases or under the supervision of such experts.

Before endoscopic procedures, all patients were given a standard premedication consisting of intravenously administered pentazocine (7.5-15 mg) and diazepam (3-10 mg) or midazolam (3-10 mg), the dose depending on age and tolerance. Patients fasted for a minimum of 24 h with a drip infusion of 2 L after the procedure. They received protease inhibitor (nafamostat mesilate, 20 mg/d) infusion, which was started before the procedure, for 2 d and antibiotics (sulbactam/cefoperazone, 2 g/d) infusion for 3 d. No patients underwent pancreatic stent placement for prevention of pancreatitis.

A diagnosis of post-ERCP pancreatitis was made based on the presence of abdominal pain with an increase in serum amylase level greater than the upper normal limit at 24 h after the procedure. The severity of pancreatitis was classified according to Cotton’s criteria as: mild if additional hospitalization for 1-3 d was required; moderate if additional hospitalization for 4-10 d was required; and severe if hospitalization for more than 10 d was needed, as well as in cases of hemorrhagic pancreatitis, phlegmon, or pseudocyst[4].

Fisher’s exact probability test, Student’s t test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used for statistical analyses where appropriate. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using StatMate III (ATMS Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Between January 1999 and December 2002, 1291 ERCP-related procedures (839 for diagnostic purposes, 452 for therapeutic ones) were performed. Table 1 depicts the characteristics and diagnoses of the patients.

| Parameters | Results |

| No. of patients (n) | 1291 |

| Mean age (yr, range) | 64 (12-96) |

| Male:female | 738:553 |

| Pancreatic duct opacification | 875 (68%) |

| Difficult bile duct cannulation | 107 (8%) |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 266 (20) |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 270 (20%) |

| Biliary stent placement | 60 (112%) |

| Papillary balloon dilatation | 50 (3.8%) |

| Cytology of the bile/pancreatic juice | 53 (4.1%) |

| Biopsy of the bile/pancreatic duct | 78 (6.0%) |

| Gallbladder stone | 488 (38%) |

| Choledocholithiasis | 313 (24%) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 75 (6%) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 73 (6%) |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 63 (4%) |

| Ampullary cancer | 23 (2%) |

| Pancreaticobiliary maljunction | 20 (2%) |

Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 47 (3.6%) patients (mild, 25 cases; moderate, 20; and severe, 2). No procedure-related deaths occurred in any of the patients. The evaluated risk factors of pancreatitis are shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis showed one factor to be significant: biliary stent placement without sphincterotomy performed because of coagulopathy or severe illness. All the patients who developed mild or moderate post-ERCP pancreatitis improved with conservative therapy. One patient who developed pancreatitis after stent placement without sphincterotomy immediately improved after biliary sphincterotomy was performed the next day.

| Pancreatitis (+)(n = 47) | Pancreatitis (-)(n = 1244) | P | |

| Male:female | 31:16 | 707:537 | 0.21 |

| Pancreatic duct opacification | 37 (78%) | 838 (67%) | 0.10 |

| Difficult bile duct cannulation | 7 (14%) | 100 (8%) | 0.09 |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 13 (28%) | 253 (20%) | 0.22 |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 12 (26%) | 258 (20%) | 0.42 |

| Biliary stent placement | 10 (21%) | 150 (12%) | 0.06 |

| Biliary stent placement without sphx1 | 5 (10%) | 42 (3%) | 0.026 |

| Papillary balloon dilatation | 4 (8%) | 46 (4%) | 0.20 |

| Cytology of the bile/pancreatic juice | 4 (8%) | 49 (3.9%) | 0.12 |

| Biopsy of the bile/pancreatic duct | 2 (4%) | 76 (6%) | 0.60 |

| Gallbladder stone | 15 (32%) | 433 (34%) | 0.68 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 15 (32%) | 298 (24%) | 0.21 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 5 (10%) | 70 (6%) | 0.14 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 3 (6%) | 70 (6%) | 0.92 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 5 (10%) | 58 (4%) | 0.12 |

| Ampullary cancer | 0 | 23 (2%) | 0.70 |

| Pancreaticobiliary maljunction | 0 | 20 (2%) | 0.78 |

There were two patients who developed severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. One patient (61-year-old male) underwent pancreatography and IDUS of the bile duct without sphincterotomy in order to estimate pancreatolithiasis and hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Abdominal pain and high fever continued for 9 d after the procedure. CT demonstrated a pseudocyst 4 cm in diameter surrounding the pancreatic body. In the other patient (51-year-old female), cholangiography was attempted due to suspicion of choledocholithiasis. Multiple pancreatic duct opacifications were performed, but cannulation of the bile duct was unsuccessful. She complained of abdominal pain and had a high fever after the procedure, and CT showed a swollen pancreas and a fluid collection surrounding the pancreas. Both of those patients showed clinical improvement after intensive care without the need for surgical treatment.

Hyperamylasemia after the procedure was observed in 38% (490 patients). Of these patients, the onset of an increase in the level of amylase was seen in 83% (405 patients: group 1) at 3 h, in 10% (51 patients: group 2) at 6 h, and in 6.9% (34 patients: group 3) at 24 h after ERCP. Of the 47 patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis, 42 (89%) belonged to group 1, 3 (6%) to group 2, and 2 (4%) to group 3 (group 1 vs group 2 or 3, P < 0.05). The correlation between the change in amylase level and pancreatitis is shown in Table 3. The frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis was closely related to an increased degree of serum amylase level after the procedure. There was a significant difference in the frequency of pancreatitis between patients with an amylase level more than three times the upper normal limit at 3 h after ERCP and those with an amylase level less than three times the upper normal limit (21% vs 0.7%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in frequency of pancreatitis between patients with an amylase level more than five times the upper normal limit at 24 h after ERCP and those with an amylase level less than five times the upper normal limit (49% vs 0.5%, P < 0.001).

| Serum amylase values | Pancreatitis rate | ||||

| 3 h | 6 h | 24 h | |||

| > 10 times | 39% (12/31) | 21% b | 44% (26/59) | 59% (27/46) | 49% d |

| 5-10 times | 31% (14/45) | 18% (9/49) | 38% (14/37) | ||

| 3-5 times | 20% (10/49) | 8% (5/57) | 6% (3/47) | 0.5% d | |

| 2-3 times | 5% (3/63) | 5% (3/61) | 6% (3/49) | ||

| 1-2 times | 1% (3/217) | 0.7% b | 1% (2/196) | 0% (0/206) | |

| ≤normal | 1% (5/886) | 1% (2/869) | 0% (0/906) | ||

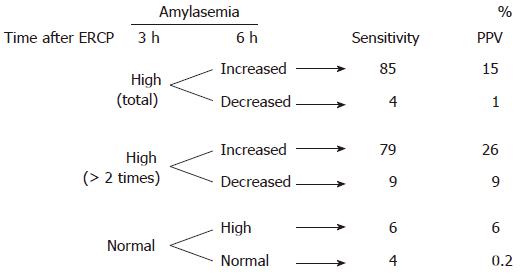

Of the 260 patients with an amylase level higher than normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by an increase at 6 h, 40 patients (15%) developed pancreatitis. On the contrary, pancreatitis occurred in only 2 (1.4%) out of 145 patients with an amylase level higher than normal at 3 h after ERCP followed by a decrease at 6 h (15% vs 1.4%, P < 0.001). Of the 143 patients with a serum amylase level higher than two times the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by an increase at 6 h, 37 patients (26%) developed pancreatitis. On the contrary, pancreatitis occurred in only 4 (9%) out of 45 patients with an amylase level higher than two times the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by a decrease at 6 h (26% vs 9%, P < 0.05).

Table 4 and Figure 1 show the sensitivity and positive predictive value of the serum amylase level and its change as predictive factors of post-ERCP pancreatitis. An increase in serum amylase level at 3 h after ERCP followed by elevation at 6 h had a sensitivity of 85% in predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis. On the other hand, a decrease in serum amylase level at 6 h had a positive predictive value of only 1%. An increase in serum amylase level more than two times the upper normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by elevation at 6 h had a positive predictive value of 26% for post-ERCP pancreatitis. An increase in serum amylase level more than three times the upper normal limit at 3 h after ERCP followed by elevation at 6 h had a positive predictive value of 32% in predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis.

| Time after ERCP | Amylase level | Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) |

| 3 h | > Upper normal limit | 89 | 10 |

| > 2 times | 83 | 21 | |

| > 3 times | 77 | 29 | |

| > 5 times | 55 | 34 | |

| > 10 times | 26 | 39 | |

| 6h | > Upper normal limit | 96 | 11 |

| > 2 times | 91 | 19 | |

| > 3 times | 85 | 24 | |

| > 5 times | 74 | 32 | |

| > 10 times | 55 | 44 |

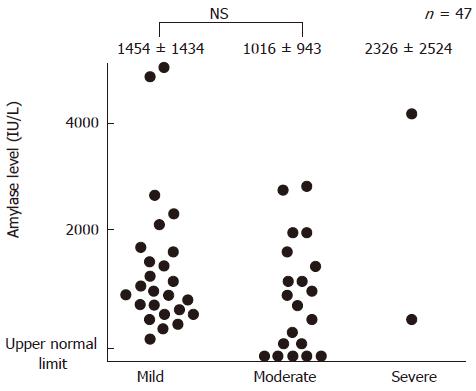

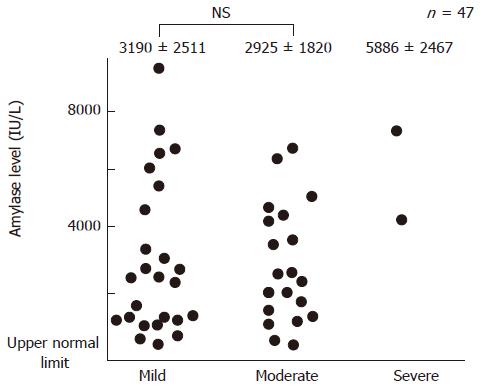

Of the 47 patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia at 3 h after ERCP was observed in 42 (89%) cases. Elevation of amylase level at 3 h after ERCP followed by an increase at 6 h occurred in 40 (85%) patients. The mean serum amylase levels at 3 h, 6 h, and 24 h after ERCP in the patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis were 1305 ± 1293 IU/L, 2731 ± 2349 IU/L, and 2364 ± 1746 IU/L, respectively. The correlation between the change in serum amylase level and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis is shown in Figures 2 and 3. There was no correlation between the two phenomena. The onset of pancreatic-type pain was observed at 0-3 h, 3-6 h, and 6-24 h in 14 (30%), 14 (30%), and 19 (40%) patients, respectively.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis remains the most common and feared complication of ERCP with an incidence ranging from 1.8% to 7.2%[1-4]. Several factors may be involved independently or in combination in the development of pancreatitis, such as mechanical injury from instru-mentation of the pancreatic duct, hydrostatic injury from over-injection, and chemical or allergic injury to contrast medium. Young age, female gender, difficulty in bile duct cannulation, pancreatic sphincterotomy, papillary balloon dilatation, prior ERCP-induced pancreatitis, and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction have been considered to be risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis[1-3,22,23]. In our study, biliary stent placement without sphincterotomy was recognized as a risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis by univariate analysis. A biliary stent placed without sphincterotomy may occlude the common channel or the pancreatic duct orifice, which may result in sphincter trauma or elevation of the pressure in the pancreatic ductal system followed by pancreatitis.

Although prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis has remained elusive for many years, various approaches have been proposed in the past two decades. Pancreatic stent placement and pharmacological treatment have been reported as being effective for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis[5-16]. The efficacy of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement has been established by several prospective randomized controlled trials[5-8]. Tarnasky et al[6] reported that pancreatic stent (5 Fr or 7 Fr in diameter, 2 cm or 2.5 cm in length) placement reduced the prevalence of post-ERCP pancreatitis from 26% to 7% in patients with pancreatic sphincter hypertension who had undergone biliary sphincterotomy. Fazel et al[7] reported that pancreatic stenting (5 Fr, 2 cm or 5 Fr nasopancreatic catheter) reduced the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis from 28% to 5% in patients at high risk of this compli-cation due to difficult cannulation, the performance of sphincter of Oddi manometry, and/or the performance of sphincterotomy. Thus far, indications for pancreatic stent placement remain controversial and unresolved.

Pharmacological prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis has been a debated question[9-16]. Administration of gabexate mesilate (1 g, bid) has been reported to be effective for preventing pancreatitis in a prospective randomized controlled trial involving 418 patients[9]; the incidence of pancreatitis was reduced 8-old in the treatment group as compared with the placebo group (2% vs 16%). The need for long-term administration was disadvantageous in terms of practical use in an outpatient setting and cost effectiveness. Another study demonstrated that a 6-h infusion of gabexate mesilate (500 mg) was of equivalent efficacy compared with a 12-h infusion (1 g)[10]. Administration of somatostatin has also been considered to be effective for preventing pancreatitis[11-14]. However, a recent study by Andriulli et al[15] showed no beneficial effect of gabexate mesilate (500 mg, qid) or somatostatin (750 μg, qid), compared with a placebo group, administered in high-risk patients. A major problem concerning pharmacological studies for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis is inclusion of unselected patients with a low risk of pancreatitis, thereby precluding adequate power to show a statistically significant difference in the outcome of the regimen. Another problem is that the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis in control groups is different in each study. Furthermore, the case population and/or the definition of post-ERCP pancreatitis have also been different in each trial.

Although several methods of preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis may be effective, it is impossible to completely prevent this particular complication[5-16]. Early recognition of pancreatic damage after the procedure is indispensable. Although clinical symptoms are reliable indicators of pancreatic inflammation, in a reported study, about 30% of the patients who developed post-ERCP pancreatitis showed no clinical signs at 2 h after the procedure[17]. Our data also demonstrated similar results. Utility of the measurement of serum amylase and lipase has been reported for early diagnosis of pancreatitis[17-21]. Since there are two types of serum amylase, i.e., the salivary-type and pancreas-type, the measurement of pancreatic-type amylase would be more reliable for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis. Unfortunately, the measurement of the subtype of amylase or other pancreatic enzyme was not available in our institution due budgetary limitations. Testoni et al[18] concluded that the level of serum amylase measured 4 h after endoscopic sphincterotomy was the most reliable predictor of post-ERCP pancreatitis, as more than two-thirds of cases of pancreatitis occurred among the patients whose 4-h amylase level was higher than five times the normal upper limit. Gottlieb et al[7] found that a 2-h serum amylase level of less than 276 U/L (normal: < 114 U/L) had a negative predictive value of 97% in predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis and proposed an algorithm for discharge management after ERCP that incorporated this finding. Many markers, however, have a high negative predictive value in their prediction because of low frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis. On the other hand, Testoni et al[24] indicated that pain at 24 h associated with amylase levels greater than 5 times the normal upper limit is the most reliable indicator of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Although serum amylase levels at 24 h after the procedure appear to be more sensitive than those at the 2 h or 3 h, late recognition is less meaningful since additional therapy for preventing pancreatitis should be started early. There have been many reports describing the sensitivity and specificity of serum amylase level for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis a certain point of time (e.g., 4 or 24 h after the procedure)[18-20,24]. However, there has been neither detailed description of the change in serum amylase level after ERCP nor discussion of the possibility that such change may be useful in predicting the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

We prospectively evaluated the relationship between the changes of serum amylase level and post-ERCP pancreatitis in a large series of patients. Our study, however, had several limitations. First, the consensus definition of post-ERCP pancreatitis[4] was not applied in this study. Second, the routine administration of protease inhibitor might have influenced the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis, although its level was similar to that of previously reported studies[1-4].

Despite these limitations, we consider our data to be useful in the prediction of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis was closely related to an increased degree of serum amylase level at 3 h after the procedure. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was found to be associated with an increase in serum amylase level more than two times the normal limit at 3 h after ERCP with elevation at 6 h. Therefore, when hyperamylasemia (higher than two times the normal upper limit) is observed at 3 h after ERCP, serum amylase concentration should be measured at 6 h after the procedure. A decrease in serum amylase level at 6 h after ERCP suggests the unlikelihood of development of post-ERCP pancreatitis. As delay in the start of treatment is occasionally fatal in the management of patients with pancreatitis, it would appear to be prudent to start treatment for post-ERCP pancreatitis based on such data.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 614] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, Wong RC, Ferrari AP, Montes H, Roston AD, Slivka A, Lichtenstein DR, Ruymann FW. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2038] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Smithline A, Silverman W, Rogers D, Nisi R, Wiersema M, Jamidar P, Hawes R, Lehman G. Effect of prophylactic main pancreatic duct stenting on the incidence of biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Obana T. The efficacy and safety of prophylactic pancreatic duct stent (Pit-stent) placement in patients at high-risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Dig Endosc. 2007;in press. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cavallini G, Tittobello A, Frulloni L, Masci E, Mariana A, Di Francesco V. Gabexate for the prevention of pancreatic damage related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gabexate in digestive endoscopy--Italian Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:919-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Masci E, Cavallini G, Mariani A, Frulloni L, Testoni PA, Curioni S, Tittobello A, Uomo G, Costamagna G, Zambelli S. Comparison of two dosing regimens of gabexate in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2182-2186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bordas JM, Toledo-Pimentel V, Llach J, Elena M, Mondelo F, Ginès A, Terés J. Effects of bolus somatostatin in preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic pancreatography: results of a randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poon RT, Yeung C, Lo CM, Yuen WK, Liu CL, Fan ST. Prophylactic effect of somatostatin on post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:593-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Poon RT, Yeung C, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Lo CM, Tang A, Fan ST. Intravenous bolus somatostatin after diagnostic cholangiopancreatography reduces the incidence of pancreatitis associated with therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52:1768-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arvanitidis D, Anagnostopoulos GK, Giannopoulos D, Pantes A, Agaritsi R, Margantinis G, Tsiakos S, Sakorafas G, Kostopoulos P. Can somatostatin prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Andriulli A, Solmi L, Loperfido S, Leo P, Festa V, Belmonte A, Spirito F, Silla M, Forte G, Terruzzi V. Prophylaxis of ERCP-related pancreatitis: a randomized, controlled trial of somatostatin and gabexate mesylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:713-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tsujino T, Komatsu Y, Isayama H, Hirano K, Sasahira N, Yamamoto N, Toda N, Ito Y, Nakai Y, Tada M. Ulinastatin for pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gottlieb K, Sherman S, Pezzi J, Esber E, Lehman GA. Early recognition of post-ERCP pancreatitis by clinical assessment and serum pancreatic enzymes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1553-1557. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Testoni PA, Caporuscio S, Bagnolo F, Lella F. Twenty-four-hour serum amylase predicting pancreatic reaction after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Testoni PA, Bagnolo F, Caporuscio S, Lella F. Serum amylase measured four hours after endoscopic sphincterotomy is a reliable predictor of postprocedure pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1235-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thomas PR, Sengupta S. Prediction of pancreatitis following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography by the 4-h post procedure amylase level. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:923-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Christoforidis E, Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, Tsalis K, Demetriades C, Betsis D. Post-ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia: patient-related and operative risk factors. Endoscopy. 2002;34:286-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fujita N, Maguchi H, Komatsu Y, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation for bile duct stones: A prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Testoni PA, Bagnolo F. Pain at 24 hours associated with amylase levels greater than 5 times the upper normal limit as the most reliable indicator of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |