Published online Jul 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3770

Revised: March 15, 2007

Accepted: March 21, 2007

Published online: July 21, 2007

Double common bile duct (DCBD) is a rare congenital anomaly in which two common bile ducts exist. One usually has normal drainage into the papilla duodeni major and the other usually named accessory common bile duct (ACBD) opens in different parts of upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum, ductus pancreaticus or septum). This anomaly is of great importance since it is often associated with biliary lithiasis, choledochal cyst, anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) and upper gastrointestinal tract malignancies. We recently recognized a rare case of DCBD associated with APBJ with lithiasis in better developed common bile duct. The opening site of ACBD was in the pancreatic duct. The anomaly was suspected by transabdominal ultrasonography and finally confirmed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction. According to the literature, the existence of DCBD with the opening of ACBD in the pancreatic duct is most frequently associated with APBJ and gallbladder carcinoma. In case of DCBD, the opening site of ACBD is of greatest clinical importance because of its close implications with concomitant pathology. The adequate diagnosis of this rare anomaly is significant since the operative complications may occur in cases with DCBD which is not recognized prior to surgical treatment.

- Citation: Djuranovic SP, Ugljesic MB, Mijalkovic NS, Korneti VA, Kovacevic NV, Alempijevic TM, Radulovic SV, Tomic DV, Spuran MM. Double common bile duct: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(27): 3770-3772

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i27/3770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3770

Double common bile duct (DCBD) is a rare congenital anomaly in which two common bile ducts exist. One usually has normal drainage into the duodenum and the other usually named accessory common bile duct (ACBD) opens in different parts of upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum, ductus pancreaticus or septum). Bile from different parts of the liver is drained through the ACBD. This anomaly is of great importance since it is often associated with lithiasis in the ectopic bile duct, choledochal cyst, anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) and upper gastrointestinal tract malignancies. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction is a congenital anomaly in which the pancreatic and biliary ducts are joined outside the duodenal wall forming a long common channel[1]. It is well known that APBJ is frequently associated with congenital choledochal cyst and cancer of the biliary system regardless of DCBD existence[2].

We recently recognized a rare case of DCBD associated with APBJ and lithiasis in better developed common bile duct.

A 65-year-old woman underwent cholecystectomy due to calculosis in 1980. In 1992 she had choledocholythiasis and underwent ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by the calculus extraction. After that she had no problems for several years and in 1998 she was referred again to the regional hospital and ERCP, additional sphincterotomy and calculus extraction were performed again.

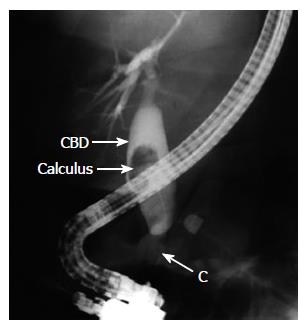

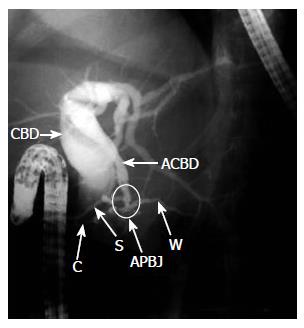

In November 2005, she was referred to our hospital because of pain in the right upper abdomen, accompanied by nausea, chills and mild fever for four weeks before admission. Her physical examination revealed only mild tenderness in the right upper abdomen. Routine laboratory analysis showed slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase, normal blood cell counts, normal renal and hepatic function and normal serum and urine amylase levels. Transabdominal ultrasonography disclosed the absence of the gallbladder due to previous cholecystectomy, the dilatation of the common bile duct of 16 mm and clearly visible choledocholithiais of 15 mm in its lumen. It is an interesting finding that, among the four parallel ducts, the most anterior was the presumed ductus choledochus, the second one probably ACBD, the third one hepatic artery and the last one the portal vein (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasonography demonstrated dilated ductus choledochus with calculus in its lumen and one bile duct without calculosis adjacent to the main duct. On ERCP, we saw two separate openings in the zone of the earlier sphincterotomized papilla duodeni major. After canulating the upper opening, the contrast medium was introduced into the dilated bile duct with big calculus in its lumen. We observed intrahepatic bile ducts of the right liver lobe, but could not fill the intrahepatic bile ducts of the left liver lobe (Figure 2). After that we canulated the lower opening on the papilla duodeni major, the contrast filled pancreatic duct, and the APBJ was revealed. We noticed that very close to the distal end of the pancreatic duct there was a communication with large bile duct and the contrast filled the previously missing part of the left liver lobe intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 3). We performed endoscopic sphincterotomy of the upper opening and extracted the calculus from the right common bile duct. No complications occurred after the procedure and the patient was without symptoms and laboratory abnormalities on the control examination six and twelve months later.

It seems that double common bile duct is a very rare anomaly in western world, since Teilum[3] identified only 24 cases in western literature until 1986. On the other hand, Yamashita reviewed Japanese literature from 1968 to 2002 and found 47 patients with this anomaly[4].

The origin of this rare anomaly could be related to a random subdivision of the hepatic diverticulum during the first week of embryogenesis[5]. The embryonic development of the liver, gallbladder system and biliary tree starts around the third week of gestation, when the primordial liver, designated as the hepatic diverticulum, is formed as an outgrowth of the endodermis in the distal part of the anterior intestine. As the hepatic diverticulum grows, its cells penetrate the mesenchyma of the ventral mesogastrium, dividing into a ventral and a dorsal bud. The primitive gallbladder is formed from the ventral bud (pars cystica). The dorsal bud (pars hepatica) divides in turn to the left and right liver lobe. As the liver and biliary tree develop inseparably, the stem of the hepatic primordium becomes the bile duct[6]. The definite lumen of the bile tree is developed by recanalisation of the epithelium. Another important feature of the bile duct development is rotation of the primitive duodenum along its longer axis, which brings the bile duct dorsal to the upper limb of duodenum. The development of double common bile duct can be ascribed to disturbances in recanalisation of the hepatic primordium[7].

If we define the ACBD as the channel of the aberrant common bile duct which did not open into the major duodenal papilla, it can open into various parts of the digestive tract, all portions of the duodenum (including the site just above the major duodenal papilla), pancreatic duct, or it can only be presented by a septum in the common bile duct. Goor and Ebert[8] made an effort to embriologically classify different types of DCBD according to the anatomic appearance of the anomaly. Saito et al[9] modified the classification based on Goor and Ebert’s morphological grouping which consisted of 4 different types of DCBD regardless of the site of the ACBD opening. On the other hand, the most important clinical feature of the DCBD seems to be the site of opening of the ACBD. Yamashita et al[4] highlighted the clinical importance of the opening site of the ACBD rather than its anatomic appearance. According to that gastric and biliary system cancer, APBJ, choledochal cysts and biliary lithiasis are the most serious complications of this condition. Gastric cancer is a possible complication usually found in patients with ACBD opening in the stomach, while gallbladder cancer and ampullary cancer usually occur in patients with ACBD openings in the second portion of the duodenum and pancreatic duct. Most of the cases of biliary system cancers are associated with APBJ. Approximately one third of the patients with DCBD have choledocholithiasis and 10% have choledochal cysts [4].

Our patient had the ACBD opening in the pancreatic duct. According to the literature, this opening site of the ACBD is most frequently associated with APBJ and gallbladder carcinoma. Our patient underwent cholecystectomy 25 years ago due to lithiasis but not to carcinoma. At the same time, she had APBJ and choledocholithiasis of the better developed common bile duct. We decided not to give surgical treatment due to patient’s age and general condition, but performed endoscopic sphincterotomy with successful stone extraction.

Treatment options of DCBD depend on the coexi-stence of APBJ and concomitant gastric or biliary system cancer. In cases without cancer, the resection of ACBD is recommended for surgical treatment. When APBJ is present, the separation of the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the gastrointestinal tract should also be performed to prevent cancer in the biliary system[10].

Precise preoperative recognition of this anomaly is rare but very important. Preoperative adequate diagnosis of biliary tree anomalies prevents surgeons from impairing the anomalous bile duct who discovered these anomalies at operation accidentally. Our case is interesting that transabdominal ultrasonography displayed a clinical suspicion of DCBD. Magnetic resonance cholangiography could also reveal the existence of this anomaly, especially when the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts were not clearly shown.[11] In such a situation careful surgical dissection should be performed followed by intraoperative cholangiography in order to avoid unnecessary injury of the bile duct.

Long-term results after treatment of DCBD depend mostly on concomitant cancer, because biliary system cancers have bad prognosis. APBJ will also influence the outcome because it is closely associated with biliary system cancer.

In conclusion, a case of DCBD associated with APBJ and choledocholithiasis was reported. In case of DCBD the opening site of ACBD is of greatest clinical importance because of its close implications with concomitant pathology. The adequate diagnosis of this rare anomaly is stressed since the possible operative complications may occur when DCBD is not recognized prior to surgical treatment.

We would thank Professor Paul Fockens, from Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, for his kind help with this work.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, Hanaoka H, Mizutani Y, Hachiya J. Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Surgery. 1998;123:391-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Komi N, Tamura T, Miyoshi Y, Kunitomo K, Udaka H, Takehara H. Nationwide survey of cases of choledochal cyst. Analysis of coexistent anomalies, complications and surgical treatment in 645 cases. Surg Gastroenterol. 1984;3:69-73. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Teilum D. Double common bile duct. Case report and review. Endoscopy. 1986;18:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamashita K, Oka Y, Urakami A, Iwamoto S, Tsunoda T, Eto T. Double common bile duct: a case report and a review of the Japanese literature. Surgery. 2002;131:676-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Knisely AS. Biliary tract malformations. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122A:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bennion RS, Thompson JE, Tompkins RK. Agenesis of the gallbladder without extrahepatic biliary atresia. Arch Surg. 1988;123:1257-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakamura K, Mitsubuchi H, Miyayama H, Yatsunami K, Ishimatsu J, Yamamoto T, Endo F. Complete absence of bile and pancreatic ducts in a newborn: a new entity of congenital anomaly in hepato-pancreatic development. J Hum Genet. 2003;48:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goor DA, Ebert PA. Anomalies of the biliary tree. Report of a repair of an accessory bile duct and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1972;104:302-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Saito N, Nakano A, Arase M, Hiraoka T. A case of duplication of the common bile duct with anomaly of the intrahepatic bile duct. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1988;89:1296-1301. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, Okada A, Katoh T, Kawaharada Y, Shimada H, Takamatsu H, Miyake H, Todani T. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:345-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Taourel P, Bret PM, Reinhold C, Barkun AN, Atri M. Anatomic variants of the biliary tree: diagnosis with MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1996;199:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |