Published online Jul 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3649

Revised: March 18, 2007

Accepted: April 7, 2007

Published online: July 14, 2007

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction that is characterized by a thick grayish-white fibrotic membrane encasing the small bowel. SEP can be classified as idiopathic, also known as abdominal cocoon, or secondary. It is difficult to make a definite pre-operative diagnosis. We experienced five cases of abdominal cocoon, and the case files were reviewed retrospectively for the clinical presentation, operative findings and outcome. All the patients presented with acute, subacute and chronic intestinal obstruction. Computed tomography (CT) showed characteristic findings of small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle in four cases. Four cases had an uneventful post-operative period, one case received second adhesiolysis due to persistent ileus. The imaging techniques may facilitate pre-operative diagnosis. Surgery is important in the management of SEP.

- Citation: Xu P, Chen LH, Li YM. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon): A report of 5 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(26): 3649-3651

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i26/3649.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3649

The sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction, which is characterized by the encasement of the small bowel by a fibrocollagenic cocoon like sac[1,2]. It was first observed by Owtschinnikow in 1907 and was called peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata[2]. SEP can be classified as idiopathic or secondary. The idiopathic form is also known as abdominal cocoon[1], the etiology of this entity has remained relatively unknown.

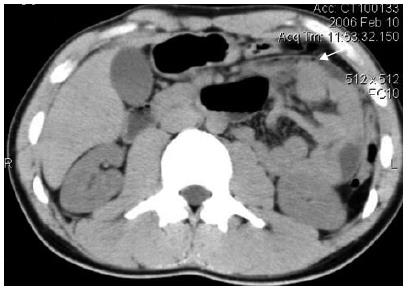

Five patients who presented to our hospital over a period of 4 years (2002-2006) with acute, subacute and chronic intestinal obstruction, were diagnosed as having abdominal cocoon on laparotomy and histopathology. The case files of these patients were reviewed retrospectively for the clinical presentation, operative findings and outcome. The average age of the patients was 37.6 years (range, 21-49 years), with 3 male and 2 female, and with no previous histories of abdominal operation, peritonitis or prolonged drug intake. All the patients presented with recurrent episodes (range, 1-6) of intestinal obstruction, i.e. colicky abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, abdominal distension and constipation, over a duration of 2 wk to 10 years prior to attending the hospital emergency. Plain abdominal X-ray showed few to multiple air-fluid levels centrally located, without free intraperitoneal gas. Contrast-enhanced abdomen computed tomography (CT) showed characteristic findings of small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle in 4 cases (Figure 1). Endoscopy of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract and biopsies from the duodenum and colon provided normal findings.

Exploratory laparotomy was performed as there was no resolution of symptoms on conservative treatment. Intraoperatively, a fibrous capsule approximately 2-10 mm thick covering abdominal viscera was revealed, in which small bowel loops were encased, with the presence of interloop adhesions. The stomach and part of colon were covered in 2 cases. The greater omentum appeared hypoplastic in 2 cases, and mesenteric vessel malformation was demonstrated in 1 case. At surgery, the covering membrane in addition to dense interbowel adhesions was freed in order to relieve the obstruction. Partial jejunectomy and jejunoileostomy were performed in 1 case due to severe interbowel adhesions and extreme jejunal dilatation which considered as nonviable.

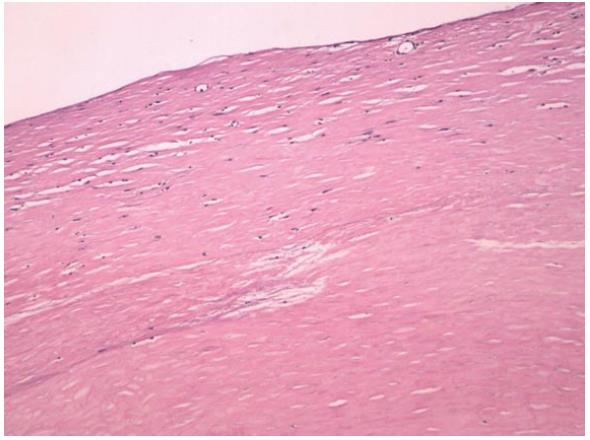

The histological examination of the membranous tissue shows proliferation of fibroconnective tissue with non-specific chronic inflammatory reaction (Figure 2). Diagnosis of idiopathic SEP was established based on the intraoperative findings and by ruling-out any other conditions explaining the patient's pathology.

Four cases had an uneventful post-operative period and passed stool spontaneously four to five days after operation, and were discharged from the hospital on the 10th-14th post-operative day, no recurrence has been described on follow-up till now. Only one patient received second adhesiolysis due to persistent ileus on d 45 after first operation, symptoms resolved four days after the second operation, and the patient is well on follow-up.

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare condition of unknown etiology in clinic. It is characterized by a thick grayish-white fibrotic membrane, partially or totally encasing the small bowel[1,2]. The fibrocollagenic cocoon can extend to involve other organs like the large intestine, liver and stomach. Clinically, it presents with recurrent episodes of acute, subacute or chronic small bowel obstruction, weight loss, nausea and anorexia, and at times with a palpable abdominal mass, but some patients may be asymptomatic[12].

SEP can be classified as idiopathic or secondary. The secondary form of SEP has been reported in association with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis[3,4]. Other rare causes include abdominal tuberculosis[5,6], Beta-blocker practolol intake[7], ventriculoperitoneal and peritoneovenous shunts[8,9], orthotopic liver transplantation[10] and recurrent peritonitis, all of which were absent in our patients. The idiopathic form also known as abdominal cocoon has been classically described in young adolescent females from the tropical and subtropical countries. The etiology of this entity has remained relatively unknown. To explain the etiology, a number of hypotheses have been proposed. These include retrograde menstruation with a superimposed viral infection[1], retrograde peritonitis and cell-mediated immunological tissue damage incited by gynecological infection[11]. However, since this condition has also been seen to affect males, premenopausal females and children, there seems to be little support for these theories[2,12,13]. Further hypotheses are therefore needed to explain the cause of idiopathic SEP. Since abdominal cocoon is often accompanied by other embryologic abnormalities such as greater omentum hypoplasia, and developmental abnormality may be an probable etiology[14,15]. In our study, in addition to greater omentum hypoplasia in 2 cases, mesenteric vessel malformation was demonstrated in one case. To elucidate the precise etiology of idiopathic SEP, further studies of cases are necessary.

Although it is difficult to make a definite pre-operative diagnosis, most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy, and a better awareness of this entity and the imaging techniques may facilitate pre-operatively diagnosis[16]. Ultrasonography may show a thick-walled mass containing bowel loops, loculated ascites and fibrous adhesions[4]. Barium small bowel series showed the ileal loops clumped together within a sac, giving a cauliflower-like appearance on sequential films[17]. In our study, we successfully diagnosed abdominal cocoon in two of these cases by a combination of abdominal CT and clinical presentations. The characteristic findings of CT include that small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen, encased by a soft-tissue density mantle which can not be contrast enhanced, and interbowel ascites was demonstrated in some cases.

Management of SEP is debated[18]. But most authors agreed that surgical treatment is required. At surgery, in addition to careful dissection and excision of the covering membrane, dense interbowel adhesions also need to be freed for complete recovery[19,20]. In order to avoid complications of postoperative intestinal leakage and short-intestine syndrome, resection of the bowel is indicated only if it is nonviable. No surgical treatment is required in asymptomatic SEP[21]. Surgical complications were reported including intra-abdominal infections, enterocutaneous fistula and perforated bowel[22]. In the present patients, beside repeated adhesiolysis was required in one case, no recurrence and complication were described in post-operative follow-up.

In summary, SEP is rare, and it is difficult to make a definite pre-operative diagnosis. But clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent episodes of small intestinal obstruction combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other plausible etiologies. Surgery is important in the management of SEP. Careful dissection and excision of the thick sac with the release of the small intestine leads to complete recovery.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sahoo SP, Gangopadhyay AN, Gupta DK, Gopal SC, Sharma SP, Dash RN. Abdominal cocoon in children: a report of four cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:987-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Afthentopoulos IE, Passadakis P, Oreopoulos DG, Bargman J. Sclerosing peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients: one center's experience and review of the literature. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1998;5:157-167. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Holland P. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin Radiol. 1990;41:19-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kaushik R, Punia RP, Mohan H, Attri AK. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon--a report of 6 cases and review of the Literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lalloo S, Krishna D, Maharajh J. Case report: abdominal cocoon associated with tuberculous pelvic inflammatory disease. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eltringham WK, Espiner HJ, Windsor CW, Griffiths DA, Davies JD, Baddeley H, Read AE, Blunt RJ. Sclerosing peritonitis due to practolol: a report on 9 cases and their surgical management. Br J Surg. 1977;64:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cudazzo E, Lucchini A, Puviani PP, Dondi D, Binacchi S, Bianchi M, Franzini M. Sclerosing peritonitis. A complication of LeVeen peritoneovenous shunt. Minerva Chir. 1999;54:809-812. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Stanley MM, Reyes CV, Greenlee HB, Nemchausky B, Reinhardt GF. Peritoneal fibrosis in cirrhotics treated with peritoneovenous shunting for ascites. An autopsy study with clinical correlations. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:571-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maguire D, Srinivasan P, O'Grady J, Rela M, Heaton ND. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 2001;182:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Narayanan R, Bhargava BN, Kabra SG, Sangal BC. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. Lancet. 1989;2:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yoon YW, Chung JP, Park HJ, Cho HG, Chon CY, Park IS, Kim KW, Lee HD. A case of abdominal cocoon. J Korean Med Sci. 1995;10:220-225. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wig JD, Goenka MK, Nagi B, Vaiphei K. Abdominal cocoon in a male: rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16:31-33. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Devay AO, Gomceli I, Korukluoglu B, Kusdemir A. An unusual and difficult diagnosis of intestinal obstruction: The abdominal cocoon. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tu JF, Huang XF, Zhu GB, Liao Y, Jiang FZ. Comprehensive analysis of 203 cases with abdominal cocoon. Zhonghua WeiChang WaiKe ZaZhi. 2006;9:133-135. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Nakamoto H. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis--a clinician's approach to diagnosis and medical treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 4:S30-S38. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Navani S, Shah P, Pandya S, Doctor N. Abdominal cocoon--the cauliflower sign on barium small bowel series. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1995;14:19. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Carcano G, Rovera F, Boni L, Dionigi G, Uccella L, Dionigi R. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case report. Chir Ital. 2003;55:605-608. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Serafimidis C, Katsarolis I, Vernadakis S, Rallis G, Giannopoulos G, Legakis N, Peros G. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon). BMC Surg. 2006;6:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang JF, Li N, Li JS. Diagnosis and treatment of abdominal cocoon. Zhonghua WaiKe ZaZhi. 2005;43:561-563. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Célicout B, Levard H, Hay J, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Pelissier E. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: early and late results of surgical management in 32 cases. French Associations for Surgical Research. Dig Surg. 1998;15:697-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Masuda C, Fujii Y, Kamiya T, Miyamoto M, Nakahara K, Hattori S, Ohshita H, Yokoyama T, Yoshida H, Tsutsumi Y. Idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis in a man. Intern Med. 1993;32:552-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |