Published online Jul 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3645

Revised: March 28, 2007

Accepted: April 18, 2007

Published online: July 14, 2007

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) of the alimentary tract often occurs in children or young adults, but may occur at any age. Symptoms are nonspecific and depend on the location of the tumor. The most often involved sites are small bowel mesentery especially the distal ileum, mesotransverse colon, or great omentum. Recurrence appears to be more frequent in the extrapulmonary lesion. Herein we demonstrate a 63-year-old male patient with mesenteric IMT, with an early recurrence after his first operation. We should be aware that if the tumor is larger than 8 cm, multinodular, omental, with ill-defined margin, with pathologically atypia, or ganglion-like cells, a close surveillence after primary surgery with image study might be necessary to detect the tumor recurrence early. Tumor recurrence may be asymptomatic, and it may act like a malignant tumor with a poor prognosis.

- Citation: Chen SS, Liu SI, Mok KT, Wang BW, Yeh MH, Chen YC, Chen IS. Mesenteric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in an elder patient with early recurrence: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(26): 3645-3648

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i26/3645.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3645

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT) are rare soft tissue tumors[1,2]. Apart from lung, the most frequently involved sites are mesentery and omentum[2]. In addition, nearly all of these extra-pulmonary IMTs occurred in children and young adults[1-5]. Here, we report a case of mesenteric IMT in an elder patient with early recurrence and it acted as a malignant tumor.

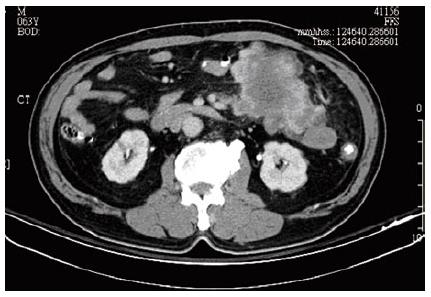

A 63-year-old patient was referred to Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital due to left lower quadrant abdominal cramping pain and a palpable mass lesion over left lower quadrant for one week. This fisherman felt a variable degree of abdominal cramping, especially after meal, for one week, in the absence of nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Physical examination revealed a palpable, non-tendered mass lesion, 10 cm in size, over left lower quadrant. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, and an 11-cm heterogeneous mesenteric mass lesion without bowel involvement but with central necrosis was found at left lower quadrant (Figure 1). No regional lymphoadenopathy was noted. Laboratory tests such as hemoglobin, hematocrit, total and differential counts of leukocytes, liver function (GOT, GPT), and renal function were within normal limits. Chest X-ray revealed no active lung lesion.

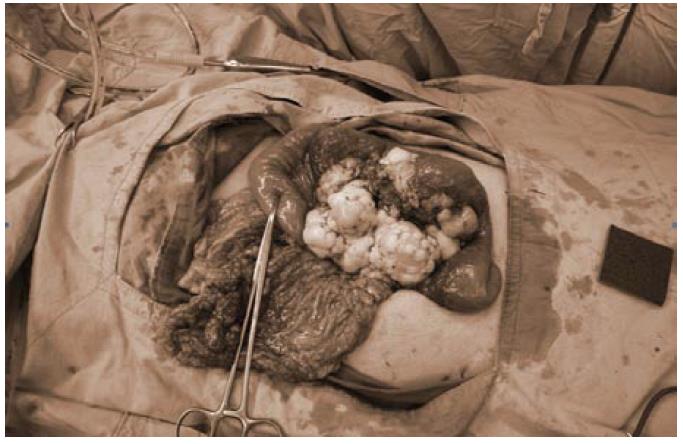

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. During operation, a tumor at the mesentery of proximal jejunum, 11 cm × 11 cm × 7 cm in size, was found with focal omentum involved (Figure 2). Segmental resection of jejunum and its mesentery was performed and the bowel was anatomized in end-to-end fashion. Another tumor nodule about 0.5 cm at the mesentery of distal ileum was also found and excised. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged 8 d after operation.

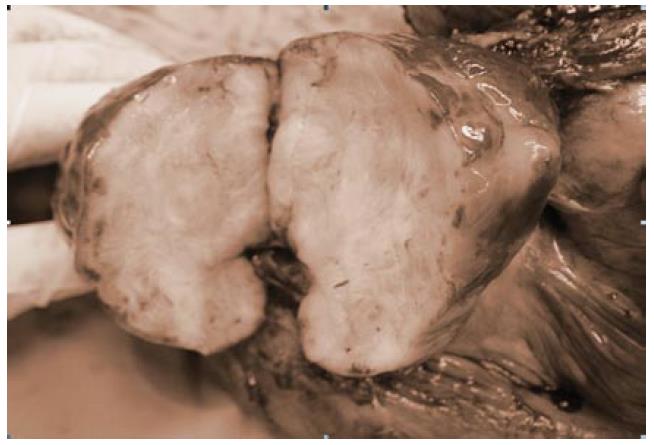

Unfortunately, tumor recurrence was noted 3 mo later during the scheduled follow-up. The patient did not felt uncomfortable, he lacked symptoms as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. Palpable mass lesion over mid-abdomen was noted. Abdominal CT revealed tumors with sizes of about 9.5 cm and 5.5 cm respectively over small bowel mesentery. The patient underwent a second exploratory laparotomy two weeks after diagnosis of tumor recurrence. The tumor, 19 cm × 17 cm × 10 cm in size, involved the mesentery of both the jejunum and ileum (Figure 3). Besides, the tumor invaded to bowel wall of small intestine and sigmoid colon. Dense adhesion of the tumor to other parts of the small bowel and transverse colon was also noted. The tumor was removed after massive resection of the jejunum, ileum, and a segment of sigmoid colon. The bowel was anatomized in end-to-end fashion. The remaining small bowel was about 120 cm in length. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged 9 d after the operation.

Grossly, the specimen of the first operation consisted of a resected jejunum and mesentery. The jejunum was 30 cm in length and 7 cm in circumference. There was a tumor located over jejunal subserosa and surrounding mesentery, 11 cm × 11 cm × 7 cm in size. The saggital cut section showed that the tumor was well-circumscribed, grayish white, and firm with foci of hemorrhage, necrosis, and cystic degeneration (Figure 4). The cut end was free of tumor cells.

The specimen of the second operation consisted of two segments of resected bowel and mesentery. The small intestines and sigmoid colon measured 90 cm and 7.5 cm in length, 4 cm and 5 cm in circumference, respectively. There was a tumor in the larger specimen over serosa and mesentery 19 cm × 17 cm × 10 cm in size and 9 cm from the intestinal cut margin. The cross section showed that the tumor was well-circumscribed, grayish white, and firm.

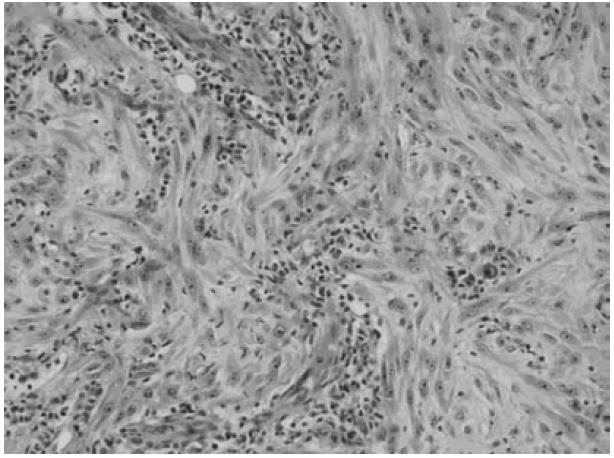

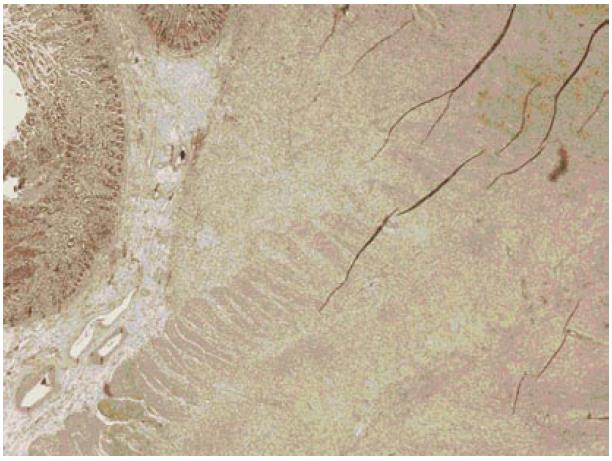

Microscopically, both tumors were composed of spindle-shaped myofibroblast cells, scanty giant cells, and many inflammatory cells embraced within collagen-abundant and thin-wall blood-abundant vessels stroma. Foci of necrosis were seen. Focal cells with mitoses area were also noted (Figures 5 and 6).

By performing immunohistochemistry, the spindle cells were shown to be positive for smooth muscle actin and HHF-35 and negative for CD34 and CD117(C-kit).

IMT was first described by Dr. Brunn in 1939[6]. Other terms that had been used to describe the same disease entity included atypical fibromyxoid tumor, plasma cell granuloma, pseudosarcomatous fibromyxoid tumor, postoperative spindle cell nodules, and inflammatory pseudo-tumors[2,3]. According to literature review, it was a rare soft tissue tumor. The most common affected organ reported was lung[7,8]. It was often asymptomatic and, with a solitary pulmonary nodule or mass detected on chest X ray and initially treated as lung cancer before the pathological diagnosis was confirmed. However, IMT can occur at any organ of the body. Among extrapulmonary IMTs, 43% were found arising from the mesentery and omentum[2,9]. Mesentery of small bowel, especially at distal ileum, transverse colon, and great omentum were the most common affected sites[1]. In the presented case, tumor seemed to arise from the mesentery of proximal jejunum. This tumor location appears to be rare[10]. The tumor did not invade to the jejunal wall in its first presentation, therefore intestinal obstruction or intussusception did not occur.

IMTs were seldom diagnosed before operation[1]. Clinical presentation of intra-abdominal IMT depended on its location and growth pattern. In general, the most common initial symptoms and signs are palpable mass, abdominal pain, weight loss, or fever. Laboratory abnormalities are present in a minority of patients and include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anemia, thrombocytosis, or hypergammaglobulinemia, which often resolve after resection[11-14]. Occasionally, IMT presented with symptoms like acute abdomen[10]. Our case presented clinically with an abdominal mass and cramping pain. The imaging finding of the tumor was not specific and it was often diagnosed, preoperatively, as other intra-abdominal tumors, such as sarcoma, lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, GIST, desmoid tumor, or carcinoid tumor[1,3]. Because most of the IMTs had extensive central necrosis[5], it is important to include IMT in the differential diagnosis of any mesenteric mass that contained large, irregular areas of necrosis.

In addition, MR findings of IMTs that occur at a variety of extrapulmonary sites had been reported. On MRI, intraabdominal myofibroblastic tumors usually exhibit an intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and a heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images[4]. On T1-weighted images after Gd-PTA, intraabdominal IMT shows a variable enhancement pattern depending on the relative amount of fibrous tissue and cellular material[4]. Thus, it might be considered to add MRI for further differential diagnosis of mesenteric mass containing large, irregular areas of necrosis.

In most instances diagnosis is possible after histopathologic examination. Spindled myofibroblasts, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells are the most frequent cellular components of IMT. Tumors composed of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts pose significant challenges in differential diagnosis because of their morphological overlap with IMT. This group includes fibrous histiocytoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, nodular fasciitis, and other pseudosarcomas as fibromatosis, myofibroblastoma, congenital-infantile fibrosarcoma, or conventional fibrosarcoma[15]. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma are characterized by marked cytological and nuclear pleomorphism, often with bizarre tumor giant cells, admixed with spindle cells, and often rounded histiocyte-like cells in varying proportions[2]. By means of immunohistochemistry, malignant fibrous histiocytoma lack cytoplasmic reactivity for vimentin and smooth muscle actin[2]. Based on the pathological patterns, extra-pulmonary IMT are histologically categorized into three types[1,5]: (1) resemble granulation tissue, nodular fasciitis; (2) resemble fibromatosis, fibrous histocytoma, smooth muscle neoplasm; (3) resemble a scar or desmoid fibromatosis. Performing immunohistochemical staining, most IMTs show cytoplasmic reactivity for vimentin and smooth muscle actin[2]. In the patient described here, the tumor was categorized to belong to the first type. Diagnosis was repeatedly confirmed by more than two pathologists in two different teaching hospitals.

In contrast to malignant fibrous histiocytoma in gross appearance, IMT showed a circumscribed or multinodular firm, white, or tan mass with a whorled flesh or myxoid cut surface. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma showed well circumscribed, expansive masses which may appear pseudocapsulated, and cut surface is variable and may include pale fibrous or fleshy areas[2].

In most reported cases, a solitary lesion was found for pulmonary or extrapulmonary IMT. However, multiple nodules might be occasionally present. The size reported ranged from 1 cm to 17 cm[3]. In comparison, most extrapulmonary IMTs, especially those of the mesenteric type, were larger in size[3]. Recurrence were documented in 18% to 40% of reported cases and appeared to occur more frequently in extrapulmonary IMTs, which were often larger than 8 cm and locally invasive in primary tumor[3,16]. In the report of Coffin and Fletcher, the recurrent rate was estimated about 25%[2]. They also pointed out that IMTs of intraabdominal, mensenteric, omental, or retroperitoneal origin and with multinodular or ill-defined gross appearance correlated with a propensity for more aggressive clinical behavior in the form of local recurrence or persistence of an incompletely resected mass[3]. In our case, the tumor was large (11 cm), multinodular, and located at mesentery. As mentioned before, the tumor recurred 3 mo after primary resection and had a clinical behavior more like malignant tumor. Therefore, a close follow-up protocol including abdominal CT scan, sonography, chest x ray, and some laboratory tests such as ESR, gammaglobulin, or Hb, might be important for patients with tumors of large size, multinodularity, an ill defined margin, or mesenteric origin.

The treatment was straightforward; resection remains to be the best method of choice. Some other treatments such as adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy have been tried in the past[3]. Unfortunately, all of these adjuvant treatments of IMT were proved to have no or only little benefit for the patient[14].

Some had pointed that IMT of the mesentery of small bowel has a very uncommon benign process[1,3]. However, Moli et al[17] found that a variety of biologic behaviors ranged from the frequently benign lesion to more aggressive variants could be seen in retroperitoneal IMTs. There is increasing cytogenetic evidence that IMT is neoplasm with actually malignant potential, as demonstrated by the presence of clonality in a few cases[18]. It is increasingly recognized that this tumor is potentially locally aggressive and capable of distant metastasis with substantial morbidity and mortality. Although most specialists believed that the prognosis couldn't be reliably predicted on the basis of the typical pathological features[3], in the report of Jerry et al, the presence of atypia and ganglion-like cells are described to be associated with recurrence or malignant transformation[19]. In the patient described here, it was estimated that, from the last OPD follow-up to the second operation, tumor size doubled in two weeks. It actually acted as a malignant tumor, however, from the basis of our secondary pathologic examinations, the tumor did not transform to a malignant lesion resembling histiocytic sarcoma. The two pathologic reports of our case were consistent in many parameters, the tumor showed a high degree cellularity and cytological atypia with ganglion-like cells. On the other hand, we must admit that some tiny or occult nodules could be possibly missed by naked eyes during first exploratory laparotomy. It might explain its early recurrence and rapid growth in our case.

In summary, intra-abdominal IMTs are clinically and radiologically difficult to differentiate from other intra-abdominal malignant tumors. In an elderly patient with an abdominal mass, it is reasonable to consider the possibility of IMT if other diagnoses are excluded. MRI might provide useful information for diagnosis pre-operatively. Since IMTs of the alimentary tract have a high potential of local recurrence, and treatments are not effective[5,14], aggressive en-bloc resection of the tumors remains the best choice of treatment for patients with IMTs. Furthermore, in case that the tumor is larger than 8 cm, multinodular, originated from omentum, ill-defined in margin, or presented with pathologically atypia, ganglion-like cells, a close follow-up after primary surgery might be necessary for an early detection of a recurrent tumor.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Mihm S E- Editor Wang HF

| 1. | Bonnet JP, Basset T, Dijoux D. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children: report of an appendiceal case and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1311-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Coffin CM, Fletcher JA. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone; Vol 2 Fibroblastic/ Myofibroblastic tumors. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 91-93. |

| 3. | Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1030] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ko SW, Shin SS, Jeong YY. Mesenteric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor mimicking a necrotized malignant mass in an adult: case report with MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Apa H, Diniz G, Saritas T, Aktas S, Ortac R, Karaca I, Karkiran A, Vergin C. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: review of the literature by means of a case report. Turkish J Cancer. 2002;32:28-31. |

| 6. | Brunn H. Two interesting benign lung tumors of contradictory histopathology. J Thorac Surg. 1939;9:119-131. |

| 7. | Bahadori M, Liebow AA. Plasma cell granulomas of the lung. Cancer. 1973;31:191-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pettinato G, Manivel JC, De Rosa N, Dehner LP. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (plasma cell granuloma). Clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:538-546. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Khoddami M, Sanae S, Nikkhoo B. Rectal and appendiceal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9:277-281. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Heim D, Ruchti C, Negri M. Acute abdomen caused by a perforated inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the jejunum. Int Surg. 2006;91:63-67. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Donner LR, Trompler RA, White RR. Progression of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor) of soft tissue into sarcoma after several recurrences. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1095-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stringer MD, Ramani P, Yeung CK, Capps SN, Kiely EM, Spitz L. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours in children. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1357-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Souid AK, Ziemba MC, Dubansky AS, Mazur M, Oliphant M, Thomas FD, Ratner M, Sadowitz PD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children. Cancer. 1993;72:2042-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanders BM, West KW, Gingalewski C, Engum S, Davis M, Grosfeld JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the alimentary tract: clinical and surgical experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Coffin CM, Dehner LP, Meis-Kindblom JM. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, inflammatory fibrosarcoma, and related lesions: an historical review with differential diagnostic considerations. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:102-110. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Dao AH, Hodges KB. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the pelvis: case report with review of recent developments. Am Surg. 1998;64:1188-1191. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Mali VP, Tan HC, Loh D, Prabhakaran K. Inflammatory tumour of the retroperitoneum--a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:632-635. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:85-101. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hussong JW, Brown M, Perkins SL, Dehner LP, Coffin CM. Comparison of DNA ploidy, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings with clinical outcome in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:279-286. [PubMed] |