Published online Jun 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3101

Revised: January 25, 2007

Accepted: January 31, 2007

Published online: June 14, 2007

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility, clinical effect and predicting factors for favorable outcome of treatment with anal plugs in fecal incontinence and retrograde colonic irrigation (RCI) in patients with fecal incontinence or constipation.

METHODS: Patients who received treatment with an anal plug or RCI between 1980 and 2005 were investigated with a questionnaire.

RESULTS: Of the 201 patients (93 adults, 108 children), 101 (50%) responded. Adults: anal plugs (8), five stopped immediately, one stopped after 20 mo and two used it for 12-15 mo. RCI (40, 28 fecal incontinence, 12 constipation), 63% are still using it (mean 8.5 years), 88% was satisfied. Younger adults (< 40 years) were more satisfied with RCI (94 % vs 65%, P = 0.05). Children: anal plugs (7), 5 used it on demand for an average of 2.5 years with satisfactory results, one stopped immediately and one after 5 years. RCI (26 fecal incontinence, 22 constipation), 90% are still using it (mean time 6.8 years) and felt satisfied. Children tend to be more satisfied (P = 0.001). Besides age, no predictive factors for success were found. There was no difference in the outcome between patients with fecal incontinence or constipation.

CONCLUSION: RCI is more often applied than anal plugs and is helpful in patients with fecal incontinence or constipation, especially for younger patients. Anal plugs can be used incidentally for fecal incontinence, especially in children.

- Citation: Cazemier M, Felt-Bersma RJ, Mulder CJ. Anal plugs and retrograde colonic irrigation are helpful in fecal incontinence or constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(22): 3101-3105

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i22/3101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3101

Fecal incontinence is a devastating complaint from patients and affects their quality of life. The prevalence of fecal incontinence is estimated to be around 5% in the general population, being higher in women than in men and up to 40% in nursing homes[1,2].

The first step in treatment of all forms of fecal incontinence is to regulate defecation with a fiber enriched diet, fiber supplementation and physiotherapy or biofeedback of the pelvic floor. When this fails, a sphincter repair is performed in patients with sphincter defect. Surgical treatments such as gracilis plasty, sacral neuromodulation (SNS), artificial sphincter or eventually a stoma are other options[3]. However, these techniques are not always successful, carry a substantial morbidity and are not generally available. Especially in non-Western countries, surgical options are very scarce. Another possibility is the use of an anal plug. This is a device consisting of compressed foam in cone shape used to close off the anus. Some patients reach continence but pelvic floor function is needed to support the plug. A recent Cochrane review showed some effects of a short-term usage, but little is known about long-term possibilities[4]. Although no research has been done in non-Western countries, they are used frequently and available even on market.

An alternative is retrograde colonic irrigation (RCI). RCI in the morning can diminish the chance of unwanted fecal loss during the day. The patient installs a rectal tube connected with a bag with 0.5-1 liter warm tap water and let this pour in, while sitting on a toilet. This “super-enema” will reach higher than the rectum and cleans the left hemicolon. A recent study about RCI reports a success rate of 41%[5].

Chronic idiopathic constipation is a common complaint in adults with a frequency of around 2%-7% in the general population, increasing up to 20% in nursery homes[6,7]. In children, a frequency of 17% has been reported[8]. Management of chronic constipation includes increasing fluid and dietary fiber intake, laxatives and increasing physical activity. Physiotherapy or biofeedback is the next step in both patients with or without slow transit or anismus[9,10].

In patients with constipation, RCI is also used to clean the bowel. One study reported an effective rate of 65%[5].

Although there are indications in the literature and clinical experience about the improvement of defecation disorders with RCI and the anal plugs, little is known about the long-term outcome.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the feasibility, effectiveness and predicting factors for a favorable long-term outcome with the use of an anal plug or RCI for fecal incontinence and constipation.

The database of the enterostomal therapists were searched for patients with fecal incontinence or constipation who received treatment with an anal plug or retrograde colonic irrigation (RCI) between 1980 and 2005. Fecal incontinence was defined according to the Vaizey criteria[11] and all patients scored higher than 12. Constipation was defined according to the Rome II criteria[12]. None of the patients responded to medical treatment or biofeedback.

Firstly, the general practitioner was approached for permission to contact the patients. The patients or their parents (in children, age < 18 years) were asked to answer questions in a questionnaire about their defecation problems (incontinence or constipation), urologic problems, medication, surgical procedures, the actual treatment used, frequency of use of anal plugs or RCI, the effect of the treatment for their complaints and quality of life (scale 1-5: 1 excellent and 5 very poor, and 1-3 satisfactory), and side effects of the treatment or procedure.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU University Medical Center.

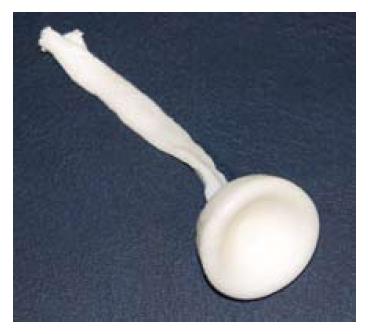

The Conveen® anal plug (Figures 1 and 2) was used (Coloplast, Amersfoort, The Netherlands). This is a disposable ( for single use) polyethylene plug. It consists of compressed foam in a conus shape, with a removal cord at one side. It is introduced in the anus with the cord hanging out. After introduction, the plug will extend within 30 s to its maximum size, thus closing off the anus. Proper instruction about introduction and removal (after 12 h or before defecation) of the plug was given. Costs of one plug are approximately €4.

For RCI, most patients used the Iryflex® (Braun Medical BV, Oss, The Netherlands) and occasionally the hand RCI from Braun or Coloplast (Figure 3). Patients were instructed about the proper use of the system. The Iryflex® pump with a reservoir was filled with hand warm tap water, the connecting tubes were prefilled with water to avoid air insufflation, and the cone was inserted. Then the pump was activated at a preset speed.

The hand system device consisted of an irrigation bag, a tube and a cone tip. The irrigation bag was hung at shoulder height and filled with 500-1000 mL of hand warm tap water. The tube was prefilled with water to avoid air insufflation. Then the lubricated cone was inserted and irrigation started. The speed is manually regulated by a clamp. The procedure was performed before or two hours after breakfast preferably. The patient was instructed to wait for the urge to defecate before removing the cone. Next evacuation of the fluid and feces could take place.

The Iryflex® pump and the tubes were replaced every six mo. The hand systems should also be replaced every 6 mo.

All patients had one visit for instruction and a second one when necessary. In addition, there was an open access for telephone consultation. Written instruction was also provided.

Results were described as medians and range. Differences among groups were assessed with a Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test when appropriate. P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

From a total of 201 patients, 101 (50%) questionaires were obtained (Table 1). Sixteen cases refused the general practioners and 84 patients did not respond. The database showed no differences between responders and non-responders in underlying disorders, age or sex.

| Anal plugs | RCI | Total | ||||

| n | Response | n | Response | n | Response | |

| Adults | 14 | 8 (57) | 79 | 40 (51) | 93 | 46 (49) |

| Children (< 18 yr) | 16 | 7 (44) | 92 | 48 (52) | 108 | 55 (51) |

| Total | 30 | 15 (50) | 171 | 88 (51) | 201 | 101 (50) |

Anal plugs: Of the 14 patients with fecal incontinence who were prescribed an anal plug, 8 patients including 6 women (median age 57 years, range 37-77) returned the questionnaire. The causes of fecal incontinence were multiple sclerosis (5), dystrophia myotonica (1), haemangioblastoma (1) and idiopathic (1). Five patients had urological problems. Four patients complained of an impact on their social life. Of the 8 patients, 5 patients stopped using the plug immediately, one patient stopped after 20 mo and two patients used the anal plugs for 12-15 mo and are still using it satisfactorily. Patients used the plug generally on demand. Major side effects of the anal plugs were displacement of the plug and leakage during diarrhea.

Retrograde colonic irrigation: Of the 79 patients including 32 women, 40 (median age 42 years, range 19-90) returned the questionnaire. There were 28 patients with fecal incontinence and 12 patients with constipation. Their demographics are shown in Table 2. No significant difference was found between patients with fecal in-continence or constipation.

| Fecal incontinence | Constipation | P | |

| Total | 28 | 12 | |

| Age (yr) | 42 | 46 | |

| Female /male | 23/5 | 9/3 | |

| Urological problems | 15 (54) | 6 (50) | |

| Gynaecological problems | 3 (11) | 3 (25) | |

| Neurological disease | 11 (39) | 3 (25) | |

| - Spinal bifida | 4 | 2 | |

| - Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 1 | |

| - Spinal injury | 3 | 0 | |

| Anal atresia | 2 | 0 | |

| Impact complaints social life | 16 (64) | 8 (67) | |

| Actual using RCI | 20 (71) | 5 (42) | 0.09 |

| Therapy satisfaction all patients | 23 (82) | 6 (50) | 0.056 |

| Therapy satisfaction among actual users | 19 (95) | 3 (60) | 0.7 |

Twenty-five patients (63%) are still using the irrigation (Table 2). The mean time of using RCI was 8.5 (range 2.5-18) years. Of the 25 patients, 8 (32%) irrigated daily, 9 (36%) 3 times a week and 8 (32%) twice or less a week. Overall, 29 patients (73%) were satisfied with the therapy. From the 25 actual users, 22 (88%) were satisfied about the therapy. There was a tendency of more actual use and satisfaction among patients with fecal incontinence, but this was not statistically significant (Table 2). Younger adults (< 40 years) were more satisfied with RCI, 94% vs 65% (P = 0.05).

Major side effects were abdominal cramps (37.5%) and the cumbersome procedure (30%) which is time consuming and difficult to take outside home. The patients who discontinued were less satisfied about the therapy (43% vs 88%, P < 0.003) and (85% > 40 vs 32% > 40, P < 0.005). Of the 25 patients who used RCI, 17 (68%) were < 40 years of age. Gender did not influence the discontinuation of the therapy. The major reason for discontinuation was the side effects.

Anal plugs: Of the16 patients with fecal incontinence using an anal plug, 7 patients including 3 females (median age 10 years, range 7-16) returned the questionnaire. The causes of fecal incontinence of the respondents were spina bifida (6) and anal atresia (1). All underwent surgical procedure(s) and 6 had urological problems. Five patients reported an impact on their social life.

Five patients felt satisfied, and used the plug generally only on demand once a week before swimming or social events. Two patients stopped using the plug immediately and after five years. The others used the tampon for an average of 2.5 years. A major side effect was displacement of the plug.

Retrograde colonic irrigation: Of the 92 patients, 48 and/or their parents including 22 females (median age 12 years, range 4-19) returned the questionnaire. There were 26 patients with fecal incontinence and 22 with constipation. Their diagnoses were spina bifida (29), anorectal malformation (7), Hirschsprungs disease (4), idiopathic constipation (5) and miscellaneous disorders (3). No difference between patients with fecal incontinence or constipation was found in demographics (Table 3).

| Fecal incontinence | Constipation | |

| Total | 26 | 22 |

| Age (yr) | 11 | 13 |

| Female /male | 14/12 | 12/10 |

| Urological problems | 22 (85) | 17 (77) |

| Any surgery | 25 (96) | 19 (86) |

| Neurological disease | 11 (96) | 3 (25) |

| - Spina bifida | 19 | 10 |

| - Hirsschprungs disease | 1 | 3 |

| - Anorectal malformation | 4 | 3 |

| - Idiopathic constipation | 0 | 5 |

| - Miscellaneous disorders | 2 | 1 |

| Impact complaints social life | 15 (58) | 14 (64) |

| Actual using RCI | 23 (88) | 20 (91) |

| Therapy satisfaction all patients | 24 (92) | 21 (88) |

| Therapy satisfaction among actual users | 23 (100) | 20 (100) |

Among all patients, 44 (90%) underwent surgical procedures and 39 (81%) had urological problems. Twenty-nine (60%) of the patients complained that the use of the rectal cleansing device had an impact on their social life.

Forty-three (90%) continued the RCI on a regular basis and were satisfied about the therapy. The mean time of using RCI was 6.8 years. A few patients complained that the device was difficult to take outside home, that the insertion piece was too big and sometimes an adjustable toilet seat was needed. No difference was found in the therapeutic outcome in patients with fecal incontinence and constipation.

When compared with adults, children tend to be more satisfied (P = 0.001). No other factors were found that predicted a successful treatment.

This study shows the long-term benefit of anal plugs in selected patients with fecal incontinence and RCI for patients with fecal incontinence or constipation, both in children and adults. The small number of patients lies in a major limitation. The response of 50% is due to the fact that some general practitioners were not permitted to approach the patients and the time span was 25 years. In spite of this, some conclusions can be made.

Our study found that anal plugs are not often prescribed. Five of the 8 (62%) adults and 2 of the 7 (14%) children stopped their use immediately due to local irritation and displacement. The seven patients who continued generally used it once a week during social events, the children mainly during swimming. The term of use however, is not very long, the longest being 5 years. Children seem to more appreciate the plug, possibly due to their swimming lessons.

Little information is found in the literature about the use of anal plugs[4,13-18]. A Cochrane review from 2005[4] looking at randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials only found four studies, from which only two were published[13,14]. In all published anal plug studies, the evaluation was only made during the study and lasted not more than 2-3 wk. Early dropout varied between 20%-65% and was less in children[13]. Continence was achieved in about 80%-90% in those who continued the therapy. The maximum time of having the plug in place was 12 h[15,18]. Size of the plug did not seem to matter much[13]. Only patients with anal atresia sometimes needed smaller plugs[14]. A study in children comparing two different types of plugs showed that plug loss was less and overall satisfaction was greater with poly-urethane plugs than poly-vinyl alcohol plugs[14].

Major side effects in all the studies are local irritation, leakage and plug loss. These local side effects prevent its daily use. No predicting factors for a successful outcome were reported in any of the studies. Our study is the first evaluating the long- term use of anal plugs and shows that in selected patients intermittent use up to 5 years is possible and especially in children is worthwhile trying.

RCI was applied in much more patients, and continuation and satisfaction were much higher, both in adults (65% and 88%) and children (90% and 100%). The average time of use was 8.5 years, ranging from 2.5 years to 18 years in adults. This indicates that RCI should be considered in patients with fecal incontinence or evacuation disorders, even when taking the response rate of the questionnaire into account. Children coped especially well with the procedure and were more pleased with the results. Besides younger age, no predictive factors were found for a successful treatment. In adults RCI was tend to be more successful in patients with fecal incontinence than in patients with constipation. The time consuming procedure and irrigation related problems are the major side effects and are often the reason for discontinuation.

A Dutch group[5] evaluated 169 (60%) of 267 patients who were offered RCI. The overall continuation was 45%. The dropout was higher in patients with fecal incontinence or soiling. Patients with evacuation disorders continued all, although not all were satisfied. The time consuming caused the discontinuation of the procedure. The median frequency of RCI was once daily. The average observation period was 4.5 years with a maximum of 13 years.

Two other groups[19-23] reported their results with RCI. A Japanese group[19] introduced RCI first successfully in 10 patients with evacuation after a lower anterior resection with defecation problems. A Danish group reported in 25 adults and 10 children, a 42% improvement in patients with fecal incontinence and 8% in patients with constipation[20]. In 21 neurological patients of the same group, these figures were 73% for fecal incontinence and 40% with constipation, respectively[21]. The lower efficacy of RCI in constipated patients was thought to be due to an overstretched, less sensitive bowel wall[22].

Irrigation requires a lot of self-motivation and con-sumes valuable time. Good instruction and feedback are mandatory. The exact mechanism behind RCI is not known. The effect of water is obviously partly due to a wash-out effect. In addition, a large amount of water generates mass movements[24].

Another cleansing treatment is antegrade colonic irrigation through an appendicostoma, a tapered ileum or a continent colonic conduit as an alternative for patients with defecation disorders[25-27]. Although results have been reported to be better, RCI requires no surgical intervention and has minimal side effects.

Although the response rate of 50% was not very high and responses in children represent in younger children also the impression from the parents, it shows that some patients do benefit from the therapy and it is worthwhile trying. Unlike surgical procedures, both anal plugs and RCI cause no harm. However, motivation does play an important role. Side effects and the cumbersome procedure with RCI are the main drawbacks with these therapies. In many European countries, these therapies have found their way and are accepted. Prospective studies including evaluation of anorectal function[28] might help predict favorable outcome and to focus on subgroups for these therapies.

In conclusion, although the response in our study was limited, these data do give an insight in the long-term use of anal plugs and RCI in patients with fecal incontinence and chronic constipation both in adults and children. This is the longest observation period ever reported.

Anal plugs are not often prescribed and few patients will continue their use. Generally they are used on demand during social events. Children seem to be more pleased with the therapy. The longest period of use reported was 5 years. Local side effects limited its use.

RCI is more often applied, continued longer and can be helpful in many, especially younger patients. Continuation varies between 63%-90% with a satisfaction of around 90%. The longest reported use was 18 years. The abdominal cramps and cumbersome procedure are a major drawback.

Patients should at least be offered a try-out with these two therapies to improve their complaints and quality of life. These treatments can be helpful, especially in non-Western countries where unfortunately less (surgical) options are available.

We are grateful to AMG Laan, EM Ekkerman, PM van Keizerswaard and SHM van den Ancker for assisting with the database and information about the treatment. We also appreciate the data management of the questionnaire by the medical students AF Amani and E Askarizadeh.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Damon H, Guye O, Seigneurin A, Long F, Sonko A, Faucheron JL, Grandjean JP, Mellier G, Valancogne G, Fayard MO. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults and impact on quality-of-life. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Melville JL, Fan MY, Newton K, Fenner D. Fecal incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2071-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Belyaev O, Müller C, Uhl W. Neosphincter surgery for fecal incontinence: a critical and unbiased review of the relevant literature. Surg Today. 2006;36:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Deutekom M, Dobben A. Plugs for containing faecal incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD005086. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gosselink MP, Darby M, Zimmerman DD, Smits AA, van Kessel I, Hop WC, Briel JW, Schouten WR. Long-term follow-up of retrograde colonic irrigation for defaecation disturbances. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Drossman DA. Idiopathic constipation: definition, epidemiology and behavioral aspects. Constipation. Petersfield (United Kingdom): Wrighton Biomedical Publishing Ltd 1994; 3-10. |

| 7. | Talley NJ. Definitions, epidemiology, and impact of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4 Suppl 2:S3-S10. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Iacono G, Merolla R, D'Amico D, Bonci E, Cavataio F, Di Prima L, Scalici C, Indinnimeo L, Averna MR, Carroccio A. Gastrointestinal symptoms in infancy: a population-based prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:432-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fernández-Fraga X, Azpiroz F, Casaus M, Aparici A, Malagelada JR. Responses of anal constipation to biofeedback treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 963] [Cited by in RCA: 973] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43-II47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Norton C, Kamm MA. Anal plug for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pfrommer W, Holschneider AM, Löffler N, Schauff B, Ure BM. A new polyurethane anal plug in the treatment of incontinence after anal atresia repair. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10:186-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sánchez Martín R, Barrientos Fernndez G, Arrojo Vila F, Vázquez Estévez JJ. [The anal plug in the treatment of fecal incontinence in myelomeningocele patients: results of the first clinical trial]. An Esp Pediatr. 1999;51:489-492. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Alstad B, Sahlin Y, Myrvold HE. [Anal plug in fecal incontinence]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1999;119:365-366. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Christiansen J, Roed-Petersen K. Clinical assessment of the anal continence plug. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:740-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mortensen N, Humphreys MS. The anal continence plug: a disposable device for patients with anorectal incontinence. Lancet. 1991;338:295-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Iwama T, Imajo M, Yaegashi K, Mishima Y. Self washout method for defecational complaints following low anterior rectal resection. Jpn J Surg. 1989;19:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Krogh K, Kvitzau B, Jørgensen TM, Laurberg S. [Treatment of anal incontinence and constipation with transanal irrigation]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999;161:253-256. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Christensen P, Olsen N, Krogh K, Bacher T, Laurberg S. Scintigraphic assessment of retrograde colonic washout in fecal incontinence and constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Christensen P, Kvitzau B, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic colorectal dysfunction - use of new antegrade and retrograde colonic wash-out methods. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:255-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Briel JW, Schouten WR, Vlot EA, Smits S, van Kessel I. Clinical value of colonic irrigation in patients with continence disturbances. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:802-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gattuso JM, Kamm MA, Myers C, Saunders B, Roy A. Effect of different infusion regimens on colonic motility and efficacy of colostomy irrigation. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1459-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Malone PS, Ransley PG, Kiely EM. Preliminary report: the antegrade continence enema. Lancet. 1990;336:1217-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krogh K, Laurberg S. Malone antegrade continence enema for faecal incontinence and constipation in adults. Br J Surg. 1998;85:974-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Williams NS, Hughes SF, Stuchfield B. Continent colonic conduit for rectal evacuation in severe constipation. Lancet. 1994;343:1321-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Felt-Bersma RJ. Endoanal ultrasound in perianal fistulas and abscesses. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:537-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |