Published online May 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2852

Revised: March 15, 2007

Accepted: March 21, 2007

Published online: May 28, 2007

AIM: To study the activity of gemcitabine and cisplatin in a cohort of patients with inoperable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

METHODS: Chemotherapy-naive patients with pathologically proven cholangiocarcinoma, receiving treatment that consisted of gemcitabine at 1250 mg/m2 in a 30-min infusion on d 1 and 8, and cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 at every 21-d cycle, were retrospectively analyzed.

RESULTS: From June 2003 to December 2005, 42 patients were evaluated. Twelve patients (28%) had unresectable disease and 30 (72%) had metastatic disease. There were 28 males and 14 females with a median age of 51 years (range 33-67) and median ECOG PS of 1 (range 0-2). A total of 171 cycles were given with a median number of cycles of 4 (range 1-6). There were 0 CR, 9 PR, 11 SD and 13 PD (response rate 21%). Grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities were: anemia in 33%, neutropenia in 22% and thrombocytopenia in 5%. Non-hematologic toxicity was generally mild. No cases of febrile neutropenia or treatment-related death were noted. The median survival was 10.8 mo (range 8.4-13 mo) and progression free survival was 8.5 mo. One-year survival rate was 40%.

CONCLUSION: Our results indicate that the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin had consistent efficacy in patients with unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Charoentum C, Thongprasert S, Chewaskulyong B, Munprakan S. Experience with gemcitabine and cisplatin in the therapy of inoperable and metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(20): 2852-2854

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i20/2852.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2852

Cholangiocarcinoma once known as an endemic cancer in the northeastern part of Thailand is now an increasingly recognized common malignancy in the north of the country. It is one of the most difficult malignancies to diagnose and it presents late with unresectable disease. Consequently, an effective and well tolerated systemic therapy is urgently needed in the battle against this deadly disease. To date, chemotherapy has played a limited role because of its lack of activity and the overall toxicity of treatment in this high risk population. As with other gastrointestinal cancers, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) as a single agent or in combination is the most tested drug for this disease. The wide range of activity of a 5-FU based regimen had been reported to range from 0% to 30%[1-3]. Many studies included a heterogeneous group of patients, with tumors arising from different anatomic sites along the biliary tract such as gall bladder cancer, periampullary cancer and cholangiocarcinoma, which may have a different biology and sensitivity to chemotherapy. Different chemotherapeutic agents have been evaluated in small uncontrolled studies with generally poor results. Among the lists, the nucleoside analog gemcitabine seems to be the most promising new agent with consistent data supporting efficacy and tolerability in biliary tract cancer[4,5]. We previously reported a phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin combination in 40 patients (38 with cholangiocarcinoma, 1 with periampullary cancer and 1 with gall bladder cancer) which produced an overall response rate of 27.5% with a median survival of 36 wk[6]. This combination has been well tolerated with predictably mild hematologic toxicity. After the completion of that study in July 2002, we continued to treat cholangiocarcinoma patients at our institution with this regimen. We hereby report the results after treatment of gemcitabine and cisplatin combination in 42 chemo-naive cholangiocarcinoma patients.

The retrospective analysis included patients with histo-logically or cytologically proven unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, seen at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital. Eligibility, schema of chemotherapy, dose of medication and evaluation criteria were similar to previous reports and briefly outlined here.

Only patients with measurable disease and an ECOG performance status of 0-2 were included. All patients had to have adequate baseline organ functions, as stated in the following: absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 1500/μL, platelet count > 100 000/μL, total serum bilirubin of 5.0 mg/dL, serum AST/ALT < 2.5 above twice the institution's normal upper limit and creatinine of less than 1.5 mg/dL. Patients who received prior chemotherapy for unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma were not included in this analysis.

Patients received gemcitabine at 1250 mg/m2 by short 30-min infusion on d 1 and 8, and cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 by 1 to 2 h intravenous infusion on d 1 of every 3-wk interval for a maximum of 6 cycles. Patients were given pretreatment intravenous hydration of at least 1 L over 2 to 3 h. The patients also received mannitol diuresis and post treatment hydration. Appropriate antiemetic regimens (e.g. ondansetron and dexamethasone) were given before and after the administration of cisplatin.

The d 8 dose of gemcitabine was reduced by 20% if an ANC > 1000-1500/μL and platelets of > 50 000-100 000/μL were observed. If ANC and platelets were lower than the above, the d 8 dose of gemcitabine was omitted. The dose adjustment criteria also based on the worst toxicity observed during the previous course. The dose of gemcitabine was reduced by 20% for neutropenic fever or a sustained ANC of less than 500/μL or platelets less than 50 000/μL for more than 5 d. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was generally not used.

Treatment was repeated at every 3-wk interval for a maximum of 6 cycles and was discontinued when unacceptable toxicities occurred, disease progressed or patients had intermittent illness that prevented further administration of treatment.

Before each chemotherapy administration, the following assessments were performed and recorded: medical history with toxicity assessment, physical examination, body weight, and PS, complete blood count and differential, and serum chemistries. The patients were seen on d 1 and 8 of each treatment cycle by a physician in the outpatient clinic; toxicities were assessed at this time. Toxicities were graded according to the NCIC CTG Expanded Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. Tumor response was assessed according to the WHO criteria, with a CT scan or ultrasound evaluation of the indicator lesions after the second cycle of chemotherapy.

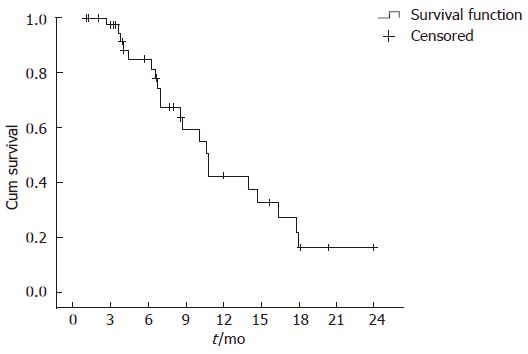

The patients were monitored and recorded for treatment-related toxicity, response and time to death. Those who received two or more cycles were evaluated for response, while those who received at least 1 cycle were evaluated for toxicity and survival. The purpose of this analysis was to determine whether the activity of this chemotherapy is reproducible in an expanded cohort of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. The primary endpoint of the analysis was the overall response rate (complete plus partial responses). A secondary objective was to document toxicity and survival. Overall survival was estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier.

From June 2003 to December 2005, 42 patients were evaluated retrospectively in the same institution. Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. There were 28 males (67%) and 14 females (33%). The median age was 51 years (range, 33 to 67) and the median ECOG performance status was 1 (range 0-2). Twelve patients (28%) had unresectable disease and 30 (72%) had metastatic disease. A total of 171 cycles of therapy were delivered and the median number of cycles was 4 (range 1-6). There were no complete responses, 9 patients (22%) achieved partial response, 11 patients (26%) had stable disease and the remaining 22 patients (52%) had PD disease progression. Severe toxicities are listed in Table 2. Grade 3 toxicities were observed in the following: anemia in 31%, neutropenia in 19% and thrombocytopenia in 5%. One patient (2%) had grade 4 neutropenia and the others had grade 4 anemia. Non-hematologic toxicity was generally mild including nausea, vomiting and fatigue. There was no episode of neutropenic fever or treatment-related death. The median time to progression was 8.5 mo and the median survival was 10.8 mo (range 8.4-13 mo) (Figure 1). One-year survival rate was 40%.

| Characteristics | No. of patients (n = 42) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Median | 51 |

| (range) | (33-67) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 14 (33%) |

| Male | 28 (67%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0-1 | 35 (83%) |

| 2 | 7 (17%) |

| Disease | |

| Unresectable | 12 (28%) |

| Metastatic disease | 30 (72%) |

| Toxicity | % |

| Anemia grade 3/4 | 31/2 |

| Neutropenia grade 3/4 | 19/2 |

| Thrombocytopenia grade 3/4 | 5/0 |

| Nephrotoxicity (Creatinine) grade≥2 | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting grade≥2 | 0 |

| Neuropathy grade≥2 | 0 |

| AST/ALT grade≥2 | 0 |

We report here one of the largest case series in cholan-giocarcinoma. The combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin achieved a response rate of 22% plus an additional disease stabilization rate of 26% giving an overall disease control rate of 48%. The median survival was 10.8 mo with a 1-year survival rate of 40% which were encouraging in the majority of patients with metastatic disease. These efficacy data compared favorably with our previous report and other trials using this gemcitabine and cisplatin combination, with slightly different doses and schedules[6-8]. However, grade 3 anemia occurred more frequently in this patient cohort. Anemia was not in the exclusion criteria for receiving or delaying the initiation of chemotherapy and about 28% of the patients already had grade 1 anemia at baseline. This could explain the high incidence of severe anemia during treatment in this analysis.

Single agent gemcitabine also demonstrated a response rate of 22% to 30% in previous reports with generally mild toxicity[4,5]. A randomized study comparing single agent gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin, similar to our regimen in the biliary cancer, is warranted and ongoing in the United Kingdom. The results of this large trial from a cooperative group will provide more definite conclusions on tolerability and efficacy between these regimens and potentially set a new reference regimen for this disease. Many new chemotherapy agents including oxaliplatin and capecitabine have also been tested in combination with gemcitabine and they were shown as well to be active regimens with a response rate ranging from 22% to 36% that make a reasonable comparative arm with the single agent gemcitabine[9,10]. Moreover, recent data suggest a therapeutic benefit of targeted agents with different mechanisms of action and toxicity such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) blockade, i.e. erlotinib, which warrants further study in combination with other existing active agents to take another step forward in treating this disease[11].

In conclusion, therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin as seen here has consistent activity and is a well tolerated therapeutic option for patients with unresectable and metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. Further study is warranted to determine the optimal dose and schedule. To clarify the survival advantage, a randomized study needs to be performed.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Falkson G, MacIntyre JM, Moertel CG. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience with chemotherapy for inoperable gallbladder and bile duct cancer. Cancer. 1984;54:965-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takada T, Kato H, Matsushiro T, Nimura Y, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T. Comparison of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and mitomycin C with 5-fluorouracil alone in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary carcinomas. Oncology. 1994;51:396-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choi CW, Choi IK, Seo JH, Kim BS, Kim JS, Kim CD, Um SH, Kim JS, Kim YH. Effects of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary tract adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:425-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kubicka S, Rudolph KL, Tietze MK, Lorenz M, Manns M. Phase II study of systemic gemcitabine chemotherapy for advanced unresectable hepatobiliary carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:783-789. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Penz M, Kornek GV, Raderer M, Ulrich-Pur H, Fiebiger W, Lenauer A, Depisch D, Krauss G, Schneeweiss B, Scheithauer W. Phase II trial of two-weekly gemcitabine in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Thongprasert S, Napapan S, Charoentum C, Moonprakan S. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in inoperable biliary tract carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:279-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park BK, Kim YJ, Park JY, Bang S, Park SW, Chung JB, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Song SY. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim ST, Park JO, Lee J, Lee KT, Lee JK, Choi SH, Heo JS, Park YS, Kang WK, Park K. A Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | André T, Tournigand C, Rosmorduc O, Provent S, Maindrault-Goebel F, Avenin D, Selle F, Paye F, Hannoun L, Houry S. Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma: a GERCOR study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1339-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cho JY, Paik YH, Chang YS, Lee SJ, Lee DK, Song SY, Chung JB, Park MS, Yu JS, Yoon DS. Capecitabine combined with gemcitabine (CapGem) as first-line treatment in patients with advanced/metastatic biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2753-2758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, Thomas J, Pitot HC, Kim G, Donehower RC, Fitch T, Picus J, Erlichman C. Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3069-3074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |