INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous melanoma is a malignancy characterized by a high mortality rate. It can metastasize to all organs, although the gastrointestinal tract is an unusual metastatic localization. In 50% of cutaneous melanomas, in fact, metastases in the gastroenteric tract are diagnosed upon autopsy, and only in 5% of cases, they are diagnosed clinically[1,2]. Intestinal metastases of cutaneous melanomas are linked to a baleful prognosis, with a survival average of 6-10 mo after surgery[3,4].

Many studies have demonstrated that only surgery can lead to a control of chronic anemia related to intestinal melanoma bleeding and resolution of the episodes of intestinal sub-occlusion. Surgery on melanoma metastases moreover, can guarantee an increase of survival, in addition to an excellent improvement in quality of life[5-7]. Intestinal metastases represent the occurrence of an occult skin melanoma in only 3%-5% of cases, in which a spontaneous regression of the cutaneous lesion happens[8]. Intestinal metastasis bleeding is extremely rare[9,10].

In order to add more information about surgical presentation of intestinal occult melanoma herein we describe a case of a young woman affected by bloody jejunal metastasis of occult cutaneous melanoma, complicated by intestinal invagination-an extremely rare case in the adult population.

CASE REPORT

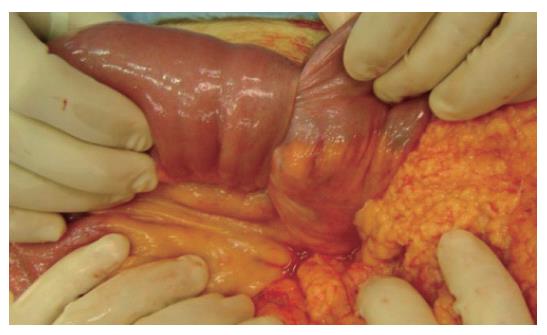

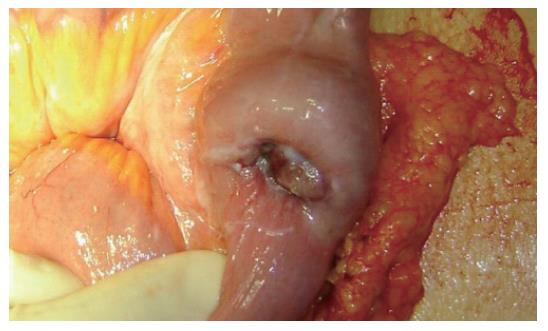

A 45-year old woman complained of continual nausea and biliary vomiting, associated with a weight loss of 5 kg. Due to localized abdominal pain, mainly in the right hypochondrium and episodes of hematemesis, the patient was admitted to our hospital. Blood tests revealed sideropenic anemia with 81 g/L haemoglobin, serum iron 100 pg/L, ferritin 23 μg/L, and fecal occult blood test (FOBT) positive in three fecal samples. A gastroscopy was performed, which showed the presence of gradeIesophagitis, moderate hiatal hernia and chronic erosive gastritis. The colonoscopy was incomplete due to the presence of colic stools. Abdominal ultrasonography highlighted a distension of the intestinal loops without signs of parenchymatous organ pathology. The patient therefore received an abdominal CT, which suggested the presence of a gastric distension with duodenum-jejunal distension and the presence of a jejunal loop with thickened walls. A second hyper-dense image inside the intestinal lumen, forming a target-shaped image was also present: typical feature of intestinal invagination (Figure 1). We therefore decided to proceed to urgent surgical operation after blood transfusion. During surgery, intra-peritoneal fluid was found and samples were removed for cytological testing. Invagination at the third jejunal loop (Figure 2) was evidenced. The presence of hypertrophic lymphatic tissue with intestinal mesenteric lymphoadenomegalia was also present. Manual resolution of the invagination was carried out. This procedure highlighted the presence of a hyperchromic ulcerated neoformation, with obvious signs of recent bleeding coming from the serosa (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Duodenum-jejunal distension and the presence of a jejunal loop with thickened walls, with a second hyper-dense image inside the same lumen, forming a target-shaped aspect characteristic of intestinal invagination.

Figure 2 Invagination at the third jejunal loop.

Figure 3 Presence of a hyperchromic ulcerated neoformation, with signs of recent bleeding of the serosa.

Thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity did not detect further replicative lesions. Resection of the third jejunal loop containing the neoformations and the whole underlying mesentery with its lymph nodes, was performed. The intestinal continuity was restored through a latero-lateral jejuno-jejunal anastomosis.

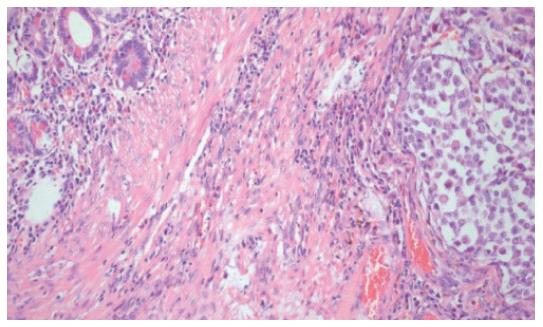

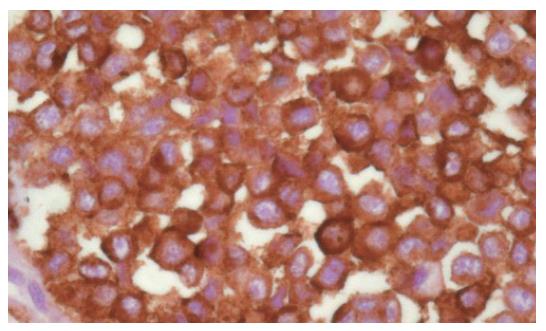

The post-operative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged after 10 postoperative days. The definitive histological examination showed the presence of an intestinal metastasis of cutaneous melanoma of unknown origin (Figures 4 and 5). The patient was then referred to an oncologic centre for the search of the primary melanoma localization. At three, six months and a year follow-up, the patient is alive and no signs of skin melanoma have been detected.

Figure 4 Ileal wall infiltrated with metastatic melanomatous cells with nuclear pseudoinclusions and nucleoli, in nest and trabecular arrangement (HE x 10).

Figure 5 Strong positivity at immunohistochemical assay for HMB45.

DISCUSSION

The peculiar rarity of this clinical case represents the principal reason for our interest. In spite of the clinical manifestation and the diagnostic-therapeutic approach adopted, this case presents many conditions that have been previously poorly documented in international literature.

Our patient presented a chronic anemia and repeated biliary vomiting that were related to the erosive gastritis and esophagitis identified by the gastroscopy, even if this did not necessarily exclude chronic bleeding from neoplastic lesions. The pre-operative CT scan of parajejunal lymphoadenomegalia prompted us to suspect the presence of a neoplastic lesion causing the jejunal invagination. Jejunal invagination in an adult, in fact, can cause 1%-3% of surgically treated intestinal occlusion but is mainly due to peritoneal adhesion or to the presence of intestinal anastomosis[11] and less frequently to a neoplasm. Melanoma intestinal metastasis is clinically diagnosed only in 3%-5% of cases, and is usually found to affect the stomach or the colon. Jejunal location is much less frequent[12] and, if present, does not show clinical signs till diagnosed at autopsy. A diagnosis based on the finding of metastatic lesions, without identification of the primary cutaneous source, as described in our report, is carried out in only 3% of melanomas. Even if the etiology of primary gastrointestinal melanomas remain undefined, some authors suggest that primary gastrointestinal melanomas are derived from melanoblastic cells of the neural crest which, migrating through the omphalomesenteric canal or APUD cells, reach the intestinal tract, undergoing neoplastic transformation[13]. Non-cutaneous melanomas represent a rare form of melanoma. In a review of 84 836 cases of melanoma, 91.2% were cutaneous, 5.2% ocular, 2.2% of unknown primary site and only 1.3% of gastrointestinal mucosa[14]. Melanomas that arise on mucosal surfaces appear to be more aggressive and are associated with worse prognosis than cutaneous melanomas. The poorer prognosis may be related to the delay in diagnosis, to their more aggressive behaviour, or to earlier dissemination because of the rich lymphatic and vascular supply of the gastrointestinal mucosa[15,16].

Our case shows that the presence of an early complication due to intestinal occlusion, through a sequential and appropriate instrumental diagnostic evaluation, gave us the opportunity to identify a rare melanotic lesion. Moreover, the right surgical approach has given us the opportunity to improve the length and quality of the life of this unlucky patient.

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF