Published online Jan 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i2.165

Revised: August 25, 2006

Accepted: October 5, 2006

Published online: January 14, 2007

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as a valuable tool in the evaluation of benign and malignant pancreatic diseases. The ability to obtain high quality images and perform fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has led EUS to become the diagnostic test of choice when evaluating the pancreas. This article will review the role of EUS in benign pancreatic diseases.

- Citation: Noh KW, Pungpapong S, Raimondo M. Role of endosonography in non-malignant pancreatic diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(2): 165-169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i2/165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i2.165

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was developed in part to better evaluate the pancreas. As the ultrasound probe lies in close proximity of the pancreas, high quality images can be obtained and FNA can be performed under ultrasound guidance. EUS is considered safer and less invasive than endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP). Thus, EUS is an important diagnostic test when evaluating the pancreas, especially in the setting of benign pancreatic diseases.

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis via EUS is based on parenchymal and ductal criteria on examination of the pancreas. The presence of 5 or more criteria is generally considered highly suggestive or diagnostic of chronic pancreatitis and the presence of 2 or less criteria generally rules out the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

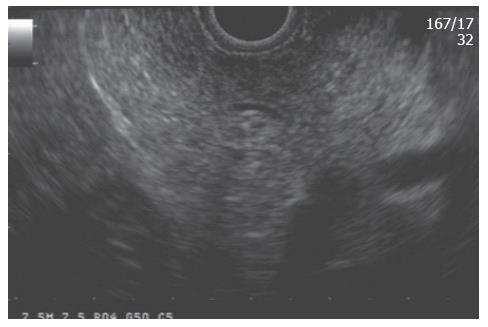

To make the EUS diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, one must understand the “normal” sonographic features of the pancreas. Several features were initially established by standard transabdominal ultrasound examinations of the pancreas. A “normal pancreas” was determined through studies such as that of Ikeda et al[1] who reported features of the pancreas in a large screening program in Japan. The pancreatic parenchyma in the absence of disease should appear homogeneous and have a “salt and pepper” appearance (Figure 1). The pancreatic duct should be seen as a smooth tubular structure coursing through the center of the pancreas. Side branches should not be visible.

The features of chronic pancreatitis can be divided into those that pertain to the parenchyma and the duct. These have been previously described by Lees[2,3] and Wiersema[4]. The parenchymal features include: hyperechogenic foci, hyperechogenic strands, lobulation, cysts, and calcifications; the ductal features include: main duct dilation, main duct irregularity, hyperechogenic main duct margins, and visible side branch ducts (Table 1).

| EUS criteria | Appearance | Histological correlate |

| Hyperechoic foci | Small distinct focus of bright echo | Focal fibrosis |

| Hyperechoic strands | Small string like bright echo | Bridging fibrosis |

| Lobularity | Rounded homogenous areas separated by hyperechoic strands | Fibrosis, glandular atrophy |

| Cyst | Abnormal anechoic round or oval structure | Cysts, pseudocyst |

| Calcification | Hyperechoic lesion with acoustic shadowing | Parenchymal calcification |

| Ductal dilation | > 3 mm in head, > 2 mm in body, > 1 mm in tail | Duct dilation |

| Side branch dilation | Small anechoic structure outside the main pancreatic duct | Side branch dilation |

| Duct irregularity | Coarse uneven outline of the duct | Focal dilation, narrowing |

| Hyperechoic duct margins | Hyperechoic margins of the main pancreatic duct | Periductal fibrosis |

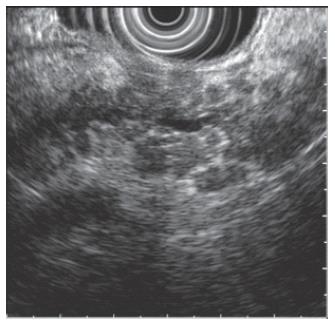

Hyperechogenic foci and strands are bright echoes or string-like structures that may correlate histologically with thickened fibrous deposits[5]. These findings can be seen in patients with a normal pancreas, especially in older individuals. When hyperechogenic strands form a distinct “lobule”, this is called lobulation (Figure 2). The pancreas thus appears inhomogeneous. This feature is more strongly associated with chronic pancreatitis as compared to hyperechogenic foci and strands alone. Calcifications of the pancreas are seen as hyperechoic or bright areas with acoustic shadowing. This feature is almost pathognomonic of chronic pancreatitis. Cysts are anechoic round or oval structures. Pancreatic cysts will be discussed further in the later sections of this article.

The size of a normal pancreatic duct is considered to be less than 3 mm in the head, 2 mm in the body and 1 mm in the tail of the pancreas. A larger duct is considered to be abnormal except in older patients when found as an isolated finding. An irregular duct correlates with focal dilation and narrowing of the main pancreatic duct. If a side branch is visible, this is considered a feature of chronic pancreatitis.

The threshold for EUS diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can be varied. A lower threshold such as greater than 3 criteria will produce a high sensitivity, but a low specificity. By contrast, using a higher threshold such as greater than 5 criteria will produce a low sensitivity and a high specificity. Thus, if the purpose of the examination is to exclude disease, a low threshold should be used. However, if the purpose is to establish the diagnosis chronic pancreatitis, a higher threshold should be used.

Another important fact is that not all factors are equal when diagnosing chronic pancreatitis. The features of lobulation and calcification are suggestive of chronic pancreatitis even in the absence of other criteria. As mentioned earlier, some features such as a dilated duct can be a “normal” finding in older individuals[1]. Currently, there is no accepted scoring system to take these factors into consideration.

Recent experimental evidence suggests the complementary role of increased levels of an inflammatory mediator such as the interleukin 8 (IL-8) in pancreatic juice and EUS to diagnose chronic pancreatitis[6]. In this study, the specificity of the combination of tests (both increased pancreatic juice levels of IL-8 and abnormal EUS) reached 100%. Until these data are confirmed in larger studies, clinical judgment must be used to make a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

The lack of a gold standard for diagnosis other than histology has pressed some investigators to explore the role of EUS-FNA in chronic pancreatitis. Hollerbach et al[7] performed EUS-FNA in 27 patients with different degrees of severity (as measured by ERP criteria). EUS was 97% sensitive but only 60% specific for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. The only advantage of EUS-FNA in this study was represented by an increased negative predictive value. Few patients developed self-limited abdominal pain after the procedure, but no major complications were observed.

More recently, DeWitt et al[8] published their experience with EUS-FNA using the trucut needle which provides a core biopsy of the pancreas for histology. The results were compared with EUS and ERP. The authors observed poor agreement between EUS and EUS with trucut biopsy and only fair agreement between ERP and EUS with trucut biopsy. Therefore, the results of these studies induce caution when considering EUS-FNA (including the trucut needle) to diagnose chronic pancreatitis.

Conversely, EUS with trucut biopsy may have a significant role when considering the diagnosis of autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Though the most characteristic endosonographic finding of this condition is diffuse pancreatic parenchyma enlargement (so-called sausage shape), there may be overlap with the non-autoimmune form of the disease or with cases of a pseudotumorous pancreatitis. Levy et al[9] reported their experience on 19 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. In 10 patients who had EUS-FNA, the material retrieved was not adequate for the cytopathologist to make the diagnosis. However, the combination of the trucut needle and the immunohistochemistry staining for IgG 4 allowed the Authors to reach the correct final diagnosis of chronic autoimmune pancreatitis in virtually all patients. The authors concluded that though the EUS with trucut helps to make the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis, this condition has still a low prevalence and a high suspicion of the disease with appropriate clinical presentation is necessary.

Improved imaging techniques and more frequent imaging of the abdomen has led to increased discovery of pancreatic cysts. These cysts pose a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge as the pathology ranges from benign pseudocysts to malignant cystic neoplasms. EUS plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of pancreatic cysts as allows for high quality images and the ability to perform fine needle aspiration.

Pseudocysts account for approximately 90% of pancreatic cystic lesions. Serous cystadenomas (SCA), mucinous cystadenomas (MCA) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) account for the majority of the remaining 10% of cysts. Pseudocysts and SCA have little or no malignant potential as opposed to MCA and IPMN which are potentially malignant or malignant. Thus, it is important to identify mucinous cystic lesions.

Pseudocysts are inflammatory fluid collections that arise in the setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis. These cysts are anechoic, thick walled structures. Septations are rare and regional inflammatory lymph nodes may be seen. Aspiration of cyst fluid will reveal dark, thin fluid containing inflammatory cells and high levels of amylase.

SCA are benign cystic lesions of the pancreas[10] with the exception of a few case reports[11-13]. They have a female predilection and are most commonly discovered in the 7th decade of life[10,14,15]. These cysts are generally microcystic, but solid and macrocystic variants have been described[16-19]. This leads to a honeycomb appearance in cross-section. Central or “sunburst” calcification is considered pathognomonic, but is found in less than 20% of cases[15,20]. Cytology obtained from EUS guided FNA of these cysts is often non-diagnostic[21]. However, when an adequate sample is obtained, this will reveal cuboidal cells without the presence of mucin.

MCA are generally macrocystic, composed of a small number of discrete compartments greater than 2 cm in size[15]. The septations are thick, irregular and occasionally a peripheral area of calcification is present[22]. It has a female predilection, mostly present in the body-tail region of the pancreas and occur most commonly in the 5th to 7th decade of life[15,20,23]. The presence of mural nodules is suggestive of invasive carcinoma. The cyst fluid of MCA is viscous and clear. Cytology will reveal mucin rich fluid with columnar mucinous cells[15].

The EUS appearance of IPMN includes segmental or diffuse dilation of the main pancreatic duct or multiple pancreatic cysts that arise from the branch ducts of the main pancreatic duct. There is an equal or slightly higher incidence of IPMNs among males than in females. The peak incidence is in the 6th and 7th decade of life[15,24]. Like MCA, the cyst fluid is viscous, clear and will contain mucinous epithelial cells[15].

Cyst fluid analysis of tumor markers has been studied to differentiate among benign and pre-malignant pancreatic cysts. In the Cooperative Pancreatic Cyst Study, the authors compared the findings of pancreatic cyst fluid of one hundred twelve patients obtained via EUS-FNA to surgical histology. EUS morphology, fluid cytology and cystic fluid tumor markers were evaluated. The results demonstrated that cyst fluid CEA levels (optimal cut-off 192 ng/mL) provided the greatest accuracy in differentiating mucinous versus non-mucinous pancreatic cysts. In addition, the accuracy of cyst fluid CEA was higher than that of EUS morphology, cyst fluid cytology or any combination of tests[25]. However, cyst fluid tumor marker values alone cannot definitively discriminate between mucinous and non-mucinous pancreatic cysts as there is overlap of CEA levels in these cysts[25,26].

Trucut biopsy of the pancreatic cyst wall has been investigated as a possible method of diagnosing pancreatic cysts. Levy et al[27] performed EUS guided trucut biopsies (EUS-TCB) in ten patients. In seven patients, a diagnosis was established and no complications were reported. Although promising, EUS-TCB can be difficult to perform in the head of the pancreas given the risk of puncturing surrounding vasculature. In addition, the curvature of the scope may not allow for effective firing of the biopsy needle.

The role of pancreatic cyst fluid molecular analysis in predicting the pathology of the pancreatic cysts has been investigated. Khalid et al[28] analyzed pancreatic cystic fluid obtained via EUS-FNA in thirty-six patients with confirmed surgical histology. The authors hypothesized that polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of DNA from whole or lysed cells shed into the cyst fluid may be predictive of cyst pathology. A high level of mutational damage would predict an underlying malignancy. In addition, as malignant cysts would have high cell turnover, cyst fluid DNA content may be higher in malignant cysts. Ten of the eleven malignant cysts carried multiple mutations as compared to no mutations in all ten benign cysts. The total amount of DNA in the malignant cysts was significantly higher than in the benign cysts.

Pain associated with chronic pancreatitis can be difficult to control[29]. Often narcotic pain medications are required, but these are associated with significant adverse effects including constipation, nausea, vomiting and dependence. As pancreatic pain is mainly transmitted through the celiac plexus, celiac plexus neurolysis or block has been employed to manage pain related to pancreatic cancer or chronic pancreatitis. Initially, this was performed surgically or percutaneously. EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis was introduced by Wiersema et al[30] which was found to be as effective as the surgical or percutaneous approaches for the management of pancreatic cancer related pain. This technique was applied to manage pain from chronic pancreatitis[31,32]. Gress et al[31] reported a series of ninety patients with chronic pancreatitis who underwent EUS-guided celiac plexus block using Bupivacaine and Triamcinolone. Fifty-five percent of patients reported a decrease in pain symptoms at 4 and 8 wk. A smaller percentage of patients experienced pain relief at 12 and 24 wk. The study was limited by a lack of a placebo arm which allows for potential bias. The use of celiac plexus block for the management of chronic pancreatitis pain remains uncertain and further studies are necessary.

Pancreatic pseudocysts may develop as sequela of acute or chronic pancreatitis. They can be asymptomatic and often resolve with time. However, when they become symptomatic or enlarge to greater than 6 cm in size, drainage is indicated. Traditionally, drainage of pseudocysts was performed surgically. However, percutaneous and endoscopic techniques have gained favor given the mortality and morbidity of surgery. The location of puncture for transgastric and transduodenal drainage of pseudocysts was determined by the bulge caused by the pseudocyst into the lumen. In the absence of a bulge, puncture of the cyst was a “blind” process increasing the risk of perforation and hemorrhage[33,34]. EUS allows for transgastric or transduodenal drainage of the pseudocyst under real time ultrasound guidance and thus minimizes the risk of complications. Various techniques have been described in the literature[34-42].

EUS is an essential tool in evaluating benign pancreatic diseases. Chronic pancreatitis and cystic lesions of the pancreas pose a diagnostic challenge. EUS carries an advantage over CT scans and endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis as it has the ability to detect parenchymal changes evident in early chronic pancreatitis. In the cases of pancreatic cysts, EUS allows for direct sampling of cyst fluid under ultrasound guidance to differentiate between cystic lesions of the pancreas. Overall, the ability to obtain important information regarding the pancreas through high quality images and FNA in a relatively safe manner is the main advantage of EUS.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Ikeda M, Sato T, Morozumi A, Fujino MA, Yoda Y, Ochiai M, Kobayashi K. Morphologic changes in the pancreas detected by screening ultrasonography in a mass survey, with special reference to main duct dilatation, cyst formation, and calcification. Pancreas. 1994;9:508-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lees WR. Endoscopic ultrasonography of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocysts. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1986;123:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lees WR, Vallon AG, Denyer ME, Vahl SP, Cotton PB. Prospective study of ultrasonography in chronic pancreatic disease. Br Med J. 1979;1:162-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wiersema MJ, Hawes RH, Lehman GA, Kochman ML, Sherman S, Kopecky KK. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with chronic abdominal pain of suspected pancreatic origin. Endoscopy. 1993;25:555-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sahai AV. EUS and chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S76-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pungpapong S, Noh KW, Al-Haddad M, Wallace MB, Woodward TA, Raimondo M. Combined pancreatic juice IL-8 concentration and EUS are highly predictive to diagnosis chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A-13. |

| 7. | Hollerbach S, Klamann A, Topalidis T, Schmiegel WH. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology for diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2001;33:824-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | DeWitt J, McGreevy K, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, Cummings O, Sherman S. EUS-guided Trucut biopsy of suspected nonfocal chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:76-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Levy MJ, Reddy RP, Wiersema MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Harewood GC, Pearson RK, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Yusuf TE. EUS-guided trucut biopsy in establishing autoimmune pancreatitis as the cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pyke CM, van Heerden JA, Colby TV, Sarr MG, Weaver AL. The spectrum of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Clinical, pathologic, and surgical aspects. Ann Surg. 1992;215:132-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abe H, Kubota K, Mori M, Miki K, Minagawa M, Noie T, Kimura W, Makuuchi M. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with invasive growth: benign or malignant? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1963-1966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujii H, Kubo S, Hirohashi K, Kinoshita H, Yamamoto T, Wakasa K. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with atypical cells. Case report. Int J Pancreatol. 1998;23:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ohta T, Nagakawa T, Itoh H, Fonseca L, Miyazaki I, Terada T. A case of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with focal malignant changes. Int J Pancreatol. 1993;14:283-289. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Fernández-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:1001-1016. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hashimoto M, Watanabe G, Miura Y, Matsuda M, Takeuchi K, Mori M. Macrocystic type of serous cystadenoma with a communication between the cyst and pancreatic duct. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:836-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lewandrowski K, Warshaw A, Compton C. Macrocystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: a morphologic variant differing from microcystic adenoma. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:871-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sperti C, Pasquali C, Perasole A, Liessi G, Pedrazzoli S. Macrocystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: clinicopathologic features in seven cases. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;28:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brugge WR. Evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions with EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:698-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432-443; discussion 444-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brugge WR. The role of EUS in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:S18-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Balci NC, Semelka RC. Radiologic features of cystic, endocrine and other pancreatic neoplasms. Eur J Radiol. 2001;38:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sarr MG, Carpenter HA, Prabhakar LP, Orchard TF, Hughes S, van Heerden JA, DiMagno EP. Clinical and pathologic correlation of 84 mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: can one reliably differentiate benign from malignant (or premalignant) neoplasms? Ann Surg. 2000;231:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kimura W, Sasahira N, Yoshikawa T, Muto T, Makuuchi M. Duct-ectatic type of mucin producing tumor of the pancreas--new concept of pancreatic neoplasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:692-709. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, del Castillo CF, Warshaw AL. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 901] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, Palazzo L, Amaris J, Soldan M, Giostra E, Spahr L, Hadengue A, Fabre M. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1516-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Reddy RP, Clain JE, Harewood GC, Kendrick ML, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Rajan E, Topazian MD. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided trucut biopsy of the cyst wall for diagnosing cystic pancreatic tumors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:974-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Khalid A, McGrath KM, Zahid M, Wilson M, Brody D, Swalsky P, Moser AJ, Lee KK, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC. The role of pancreatic cyst fluid molecular analysis in predicting cyst pathology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lankisch PG. Natural course of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wiersema MJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gress F, Schmitt C, Sherman S, Ciaccia D, Ikenberry S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block for managing abdominal pain associated with chronic pancreatitis: a prospective single center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gress F, Schmitt C, Sherman S, Ikenberry S, Lehman G. A prospective randomized comparison of endoscopic ultrasound- and computed tomography-guided celiac plexus block for managing chronic pancreatitis pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:900-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cremer M, Deviere J, Engelholm L. Endoscopic management of cysts and pseudocysts in chronic pancreatitis: long-term follow-up after 7 years of experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sahel J, Bastid C, Pellat B, Schurgers P, Sarles H. Endoscopic cystoduodenostomy of cysts of chronic calcifying pancreatitis: a report of 20 cases. Pancreas. 1987;2:447-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Soehendra N. Endoscopic pseudocyst drainage: a new instrument for simplified cystoenterostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gerolami R, Giovannini M, Laugier R. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts guided by endosonography. Endoscopy. 1997;29:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Giovannini M, Bernardini D, Seitz JF. Cystogastrotomy entirely performed under endosonography guidance for pancreatic pseudocyst: results in six patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:473-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Grimm H, Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. Endosonography-guided drainage of a pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:170-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Seifert H, Dietrich C, Schmitt T, Caspary W, Wehrmann T. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided one-step transmural drainage of cystic abdominal lesions with a large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2000;32:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Seifert H, Faust D, Schmitt T, Dietrich C, Caspary W, Wehrmann T. Transmural drainage of cystic peripancreatic lesions with a new large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1022-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided cystoduodenostomy with a therapeutic ultrasound endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:614-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |