INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic, autoimmune disease classically involving the skin, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and central nervous system. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is also an autoimmune disease causing inflammation of the liver. AIH is characterized by histological changes of interface hepatitis and plasma cell infiltration of the portal tracts, hypergammaglobulinemia, and autoantibodies. AIH reflects a complex interaction between triggering factors, autoantigens, genetic predisposition, and immunoregulatory mechanisms[1-7].

Although the liver is not a major target for damage in SLE, clinical and biochemical evidence of liver abnormalities are common. However, abnormality of liver function is not a diagnostic criterion of SLE. After careful exclusion of various etiologies of liver disease, the question remains as to whether to classify the patient as having a primary liver disease with associated autoimmune features or having liver disease as a manifestation of SLE. Whether AIH and SLE-associated hepatitis are two distinct entities remains unclear. Several clinical and histological features have been used to discriminate AIH from SLE, since complications and therapy are very different in the two conditions[1,7]. In this report, we present a patient with an overlap syndrome involving autoimmune hepatitis and SLE.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old girl was admitted in April 2002 with complaints of malaise, jaundice, polyarthralgia, abdominal distention, chest pain, and swelling of the metocarpophalangeal joints. The patient was noted to have jaundice three months prior to her presentation, but the jaundice had disappeared spontaneously. Family history was negative for rheumatic or inherited liver disease, including SLE and AIH. There was no consanguinity among the parents. On physical examination, the patient had the characteristic butterfly rash on the face, hepatomegaly (9 cm palpable below the right costal margin), splenomegaly (7.5 cm palpable below the left costal margin) and swollen metocarpophalangeal joints.

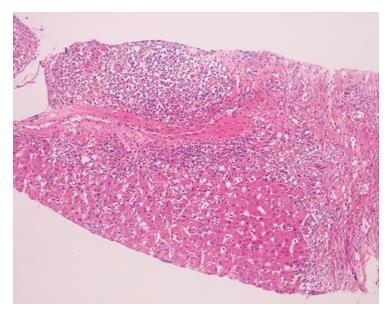

Complete blood count revealed hemoglobin of 100 g/L, white blood cell count 6000/mm3 and platelet count 409.000/mm3, a peripheral blood smear showed hemolysis with reticulocytosis. Microscopic examination of the urine revealed hematuria. Biochemical tests showed evidence of liver dysfunction. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 698 IU/L (N: 5-40 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1099 IU/L (N: 8-33 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 124 IU/L (N: 5-40 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 770 IU/L (N: 35-129 IU/L), total bilirubin 39 mg/L (N: 1-12 mg/L), conjugated bilirubin 35 mg/L (N: 0-3 mg/L), total proteins 96 g/L (N: 60-87 g/L), albumin 26 g/L (N: 32-48 g/L) and prothrombin time 17.6 s (N: 11-15 s). Serum creatinine, BUN and fibrinogen were normal. Wilson’s disease was ruled out because of normal serum ceruloplasmin, 24 h-urinary cooper levels and negative Kayser Fleischer ring. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated (117 mm/h and 100 mg/L respectively). Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia was detected. Serum immunoglobulin G and M levels were increased (3709 and 145 mg/dL respectively). Serological tests showed positive results for serum antibodies against nuclear antigen (ANA) and double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) (1/160 and 25 IU/mL respectively), and the serum levels of C3 and C4 were reduced. Tests for antiphospholipid antibody and anticardiolipin antibody were positive. Antibodies against smooth muscle (SMA) and liver/kidney microsomes (LKM) were negative. Viral serological tests including antibodies against hepatitis viruses A, B and C, Epstein Barr, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and hepatitis C virus RNA (by polymerase chain reaction) were negative. Abdominal ultrasonography and color Doppler ultrasonography revealed hepatosplenomegaly. The patient showed 7 of 11 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE which classified her as definite SLE[8]. Renal biopsy revealed class IIA kidney disease according to the WHO classification[9,10]. Liver biopsy showed chronic hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity characterized by portal infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells, interface hepatitis, confluent necrosis and areas of spotty necroses in the parenchyma. Portal fibrosis, portal-portal and portal-central fibrous bridging fibrous was noted. Histological activity score according to the Ishak modified Knodell system was 14, and the fibrosis stage was 4 (Figure 1)[11].

Figure 1 Liver biopsy revealed chronic hepatitis with severe activity, interface hepatitis, confluent necrosis and some spotty necroses within the parenchyma.

Portal fibrosis, portal-portal and portal-central fibrous bridging were also present (HE, x 100).

These findings suggested an overlap syndrome involving SLE and autoimmune hepatitis. The patient was started on treatment with oral prednisolone (Deltacortril) 2 mg/kg per day (60 mg/d) and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d. Because of steroid-related side effects and the ongoing high transaminase levels, azathioprine (AZA) was added (1 mg/kg per day), hydroxychloroquine was discontinued and prednisolone was gradually tapered. The hematuria disappeared but the serum transaminase levels (ALT: 1061 IU/L AST: 1150 IU/L) remained high after six months of therapy with prednisolone and AZA. At this stage, the dose of AZA was increased to 2 mg/kg per day and prednisolone was increased to 60 mg/d. Although clinical symptoms and laboratory findings of SLE improved, liver dysfunction persisted despite three years of treatment with corticosteroids (one course of pulse steroids) and high dose of AZA. The transaminase levels increased when the dose of steroid was reduced. Repeat liver biopsy after three years showed similar histological findings, with a mild increase in portal inflammation and interface hepatitis. The HAI score increased from 14 to 16, while the fibrosis stage remained unchanged as 4. AZA was replaced by mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg/d oraly (Cellcept® Roche), without any benefit.

DISCUSSION

The difference between the hepatic involvement in SLE and AIH has not been clearly defined due to similarities in the clinical and biochemical features. Liver involvement in patients with SLE is well documented but is considered rare. Certain factors have been implicated in the etiology of liver disease in SLE. However, the question remains whether to classify the patient as having a primary liver disease with associated autoimmune features or as having liver disease as a manifestation of SLE[1,12]. It has been suggested that patients with AIH may be at an increased risk of developing systemic connective tissue diseases. Conversely, patients with systemic connective tissue diseases may be at an increased risk of AIH[13]. Therefore, it is important to distinguish AIH from SLE, since complications and therapy are different in the two conditions. AIH may lead to end stage liver disease, while SLE may result in end stage renal disease.

The criteria for the diagnosis of AIH in adult patients have been established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG)[14]. The diagnosis requires the presence of characteristic laboratory and liver histology features and the exclusion of conditions that resemble AIH. Interface hepatitis is the hallmark of the syndrome and portal plasma cell infiltration is typical of the disorder[2]. The scoring system can also be used for children to support the diagnosis of AIH in the presence of interface hepatitis[15]. The criteria for the diagnosis of SLE have been proposed by the American College of Rheumatology[8].

Although AIH and SLE-associated hepatitis are considered as two different entities[16], both have features of an autoimmune disorder, such as the presence of polyarthralgia, hypergammaglobulinemia and positive tests for ANA, SMA, antiribonucleoprotein antibody, and anticardiolipin antibodies[17]. Therefore, reliance on serologic criteria alone may lead to diagnostic confusion. Fortunately, several histological and clinical features can differentiate AIH from SLE[16-18]. The presence of cirrhosis or periportal (interface) hepatitis, periportal piecemeal necrosis associated variably with lobular activity, and rosette formation of liver cells support the diagnosis of AIH, but do not exclude SLE. The presence of only lobular hepatitis is more compatible with SLE. In both “lupus hepatitis” (or “SLE hepatitis”) and treated AIH, the inflammatory infiltrate consists mainly of lymphocytes, whereas in untreated AIH, these cells are mixed with plasma cells. Our patient had chronic hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity characterized by focal necrosis of the hepatic cells, erosion of the lobular limiting plate, and periportal hepatitis, infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells, and presence of fibrosis in the portal areas. ANA was the only positive serological marker; its positivity is sufficient to diagnose AIH. Consequently, these findings strongly support the diagnosis of AIH[19]. The patient was evaluated for hereditary (Wilson’s disease, α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and genetic hemochromatosis), infectious (hepatitis A, B, C and CMV, EBV), and drug-induced liver injury, some of which may have autoimmune features[20-22]. When the scoring system for AIH was applied, patient had a score of 17, which is sufficient for a definite diagnosis of AIH[14].

Patients with SLE have a 25%-50% chance of developing abnormal liver tests in their lifetime. The frequency of liver dysfunction and the associated portal inflammation support the view that subclinical liver disease is a concomitant feature of SLE[23]. Histologically, the most common findings are fatty infiltration, and atrophy and necrosis of the central hepatic cells[24]. These abnormalities were not found in our patient.

Our patient met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE as well as the criteria for AIH[9,16,17,25]. She had the characteristic butterfly rash over the nasal bridge, polyarthralgia, arthritis, serositis, renal disorder, hematologic disorder, and was positive for antibodies against native DNA and nuclear antigen. She was started on prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine and achieved complete remission for her SLE but the liver disease failed to respond to the treatment.

We believe that our patient has the AIH-SLE overlap syndrome, a condition rarely seen in children[26]. In a previous report from our institute, we had described a young girl with features of AIH who developed full-blown SLE after 2 years of follow up[27]. The AIH-SLE overlap syndrome has been reported to respond rapidly to steroid therapy and the prognosis is generally good[28,29]. Atsumi T et al[31] reported that hepatic disease was not rare in SLE, and the liver function improved with steroid therapy in parallel with the stabilization of the other manifestations of SLE. In their study, liver histology revealed chronic hepatitis or steroid-induced steatosis, which were considered to be manifestations of SLE. However, our patient had features of chronic hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity, and the response to therapy was insufficient, as was confirmed by repeat biopsy of the liver.

Antiribosomal P antibody is reported to be a useful marker for differentiating SLE associated hepatitis from AIH. This antibody was found in 44% patients with SLE, but was absent in patients with AIH[31]. However, we did not carry out this test in our patient.

Corticosteroid therapy is effective in all forms of AIH and the combination of prednisone and AZA is preferred for purpose of steroid sparing. Relapse is common, and long-term low-dose prednisone or AZA therapy is the treatment of choice after a patient has had multiple relapses. Sustained remission is achievable, even after relapse and maintenance regimens need not be indefinite. Drugs such as mycophenolate mofetil cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and others promise more effective immunosuppression[32-34].

In conclusion, the AIH-SLE overlap syndrome, which has been reported rarely in adults, can also be seen in children. Children with liver dysfunction and SLE should be investigated for AIH as these two entities can occur together. Although previous studies have reported good response to immune suppression by steroids, we could not achieve complete remission in our patient.