Published online May 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i19.2747

Revised: February 12, 2006

Accepted: March 1, 2007

Published online: May 21, 2007

AIM: To analyze the local and systemic complications of high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors.

METHODS: From Aug 2001 to Aug 2004, 17 patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors were enrolled in this study. Real-time sonography was taken, and vital signs, liver and kidney function, skin burns, local reactions, and systemic effects were observed and recored before, during, and after HIFU. CT and MRI were also taken before and after HIFU.

RESULTS: All 17 patients had skin burns and pain in the treatment region; the next common complication was neurapraxia of the stomach and intestines to variable degrees. The other local and systemic complications were relatively rare. Severe complications were present in two patients; one developed a superior mesenteric artery infarction resulting in necrosis of the entire small intestines, and the other one suffered from a perforation in terminal ileum due to HIFU treatment.

CONCLUSION: Although HIFU is a one of noninvasive treatments for the recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors, there are still some common and severe complications which need serious consideration.

- Citation: Li JJ, Xu GL, Gu MF, Luo GY, Rong Z, Wu PH, Xia JC. Complications of high intensity focused ultrasound in patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(19): 2747-2751

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i19/2747.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i19.2747

There are many recurrent and metastatic solid tumor cases seen clinically, many of which have characteristics of complicated changes in anatomy, chemo-agent resistance and radiation insensitivity. Patients with such tumors are not suitable for surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. With these three treatments precluded, the possible and available treatments must be local and non-invasive, with image precise monitoring, and real-time confirmation, and these options include laser[1], cryotherapy[2], photodynamicmic therapy[3,4], radioactive particle[5] and high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)[6].

HIFU is a new treatment for solid malignant tumors, which emerged in recent years[7,8]. This approach is based on the fact that ultrasound beams can be focused and transmitted through solid tissues within the body, resulting in some bioeffects which can destroy and coagulate in-depth tissue[9] by thermal effects and cavitation. HIFU coagulates target lesions through intake skin without surgical exposure or insertion of instruments. HIFU techniques for solid tumors treatment have been reported as noninvasive and conformal with real-time monitoring[10,11]. In animal experiments and clinical studies, it has been proven that HIFU can selectively target and destroy primary or metastatic lesions through intake skin, thereby treating tumors in the liver[10,12,13] or other solid organs such as kidney[14-16], bone[17], prostate[18-20], pancreas[21], etc.

Although HIFU treatment for recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors was generally thought to be noninvasive and safe, we observed some common and even severe complications in our practice, and the aim of this study was to analyze the local and systemic complications of HIFU in patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors.

From August 2001 to August 2004, a total of 17 patients (nine males, eight females, mean age 46.9 years, range from 21 to 65 years) with confirmed recurrent and/or metastatic tumor in their abdominal cavity underwent extracorporeal HIFU ablation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of our university. We received informed consent from each patient. With multiple disciplines consulting, these patients were defined as being not suitable for surgical resection, radiotherapy or chemotherapy. There were two cases of recurrent gastric carcinoma, three recurrent colon carcinoma, three recurrent neurofibroma, one recurrent neurofibrosarcoma, one recurrent neurilemoma, one recurrent right renal carcinoma, one recurrent carcinoma of right ureter, two recurrent and metastatic ovarian cancer, one abdominal metastasis of cervical carcinoma, and one mesentery liomyoma and liposarcoma. The maximal diameter of target tumor mass ranged from 3 cm to 16 cm. A total of 19 HIFU treatment sessions were executed, with two patients with recurrent neurofibroma and colon carcinoma respectively underwent two sessions of HIFU while the other 15 patients only underwent a single session.

The HIFU therapeutic system was designed by Chongqing Haifu Co. Ltd (Chongqing, China). Briefly, as detailed in an article[7], the ultrasound (US) beam was produced by 12.6 cm diameter piezoelectric ceramic transducer with a focal length of 126 or 135 mm. In the center of the transducer, there was a 3.5 MHz diagnostic US scanner (AU3, Esaote, Italy) used for guiding the target tissue. The transducer was mounted in a waterbag filled with degassed and distilled water. The acoustic pressure field was at focal peak intensities from 2000 to 5000 Wcm-2. The treatment time with focused ultrasound varied from 3120 s to 8950 s (median, 5379.3 s), depending on the tumor size, location, depth, blood supply, adjacent large vessels. Each pulse of HIFU lasted for 20-30 s, and the interval between two successive pulses was about 10 s.

HIFU treatment was performed under general anesthesia with the patients lying either in the supine position or prone position depending on the shortest distance from transducer to target volume, so that a pulsed focused US beam produced by the transducer arrived at the target by the shortest distance from intake skin[11]. The tumor mass was selected through the directional movement of the diagnostic scanner in the target region. The target volume included only part of the tumor and did not include any of healthy marginal tissue. The tumor lesion was divided into two dimensional cross slices by scanning with real-time US. Based on the images of each slice, the target region was selected and then damaged by ejecting pulse focused ultrasound beams. Through this partial coverage, complete targeting of the tumor volume was achieved slice by slice.

During HIFU treatment, the changes of the passage tissues of focused ultrasound including skin, hypodermis and other surrounding organs were monitored by real-time US and visual inspection. US was also used to monitor the surrounding or overlying tissues, such as gallbladder, right kidney, gastrointestinal tract, bladder, etc. The vital signs were continuously observed and electrocardiography was taken during HIFU treatment.

Immediately after HIFU treatment, we observed pain in the therapy area with variable levels. We also collected blood and urine samples for routine tests such as hepatic and renal functions. Three days after HIFU, we used US to check changes in adjacent organs, such as the exterior and interior hepatic bile duct, gallbladder, right kidney, and gastric-intestinal tract. One month after HIFU, patients underwent re-scanning by computerized tamography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate the therapeutic effects of HIFU as well as changes of adjacent tissues.

During HIFU treatment, no significant changes of vital signs or electrocardiography were shown in any of the 17 patients.

Changes of vital signs: three patients had a fever below 38°C, and hypertension was found in two patients.

Skin burns: All 17 patients had skin burns of varying degrees, most of which located on the skin directly in the pathway of ultrasound; however, a minority of skin burns (three cases) were located on the opposite side to the pathway of transmitting focused ultrasound. Eight cases had erythematous burns (first grade), eight cases displayed blister burns (second grade), and one patient with recurrent right renal carcinoma was found with deep burns (third grade).

Pain in the treatment region as classified by the international standard: two cases were painless, five cases felt mild pain (first grade) and did not need analgesia; nine patients reported moderate pain (second grade) and needed non-steroid analgesia to relieve the pain; and one patient with severe pain needed morphine.

Dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract: Mild enteroparalysis was found in 15 patients who recovered completely within 3 d.

Impairments of hepatic and renal function: After HIFU treatment, two cases were found with a slight elevation in glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) or glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) activity, both of which were below 80 units. One case was found with a slight elevation of creatinine in the blood serum.

Hematuria: Gross hematuria was found in 1 patient with abdominal metastasis of cervical carcinoma which was attributed to damage of the bladder. Another patients with recurrent carcinoma of the right ureter displayed erythrocytes (+++) in a urine sample 3 d after HIFU.

Impairment of peripheral nerves: skin numbness in the treatment region was found in five patients.

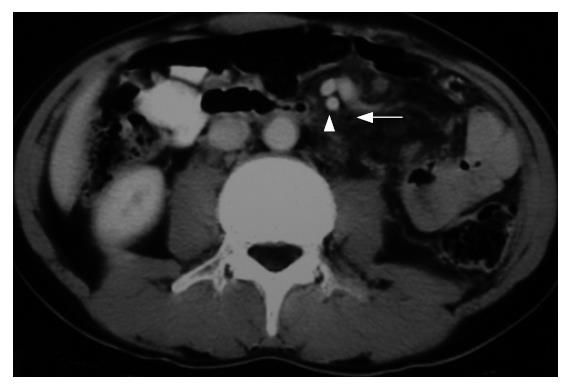

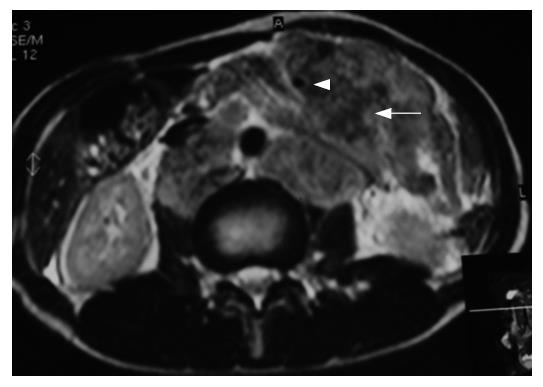

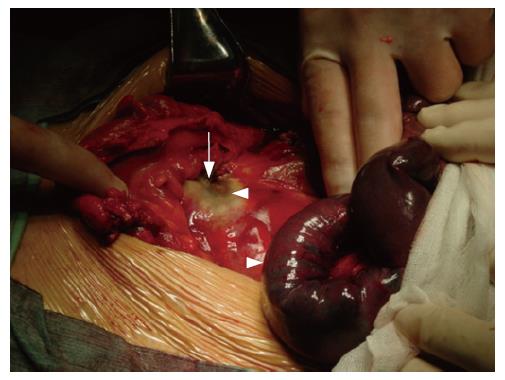

Superior mesentery arterial infarction: One day after HIFU, one male patient (43 years old) with recurrent colon carcinoma was found symptoms of ileus, including abdominal pain and distension tenderness, vomiting, rebound tenderness, and hypoactive bowel sounds. Significant increase in leukocyte and neutrophil granulocytes in a regular blood test was shown on d 3 and noncoagulative haematodes fluid was extracted during abdominal paracentesis. Furthermore, a white coagulative necrotic tumor zone and entire small intestinal ischemia necrosis due to superior mesentery arterial infarction was found in a sequentially emergent exploration of abdomen. Surgical resection of the entire small intestine resection was conducted and resulted in the need for total intravenous nutrition (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Perforation in terminal ileum: during HIFU, another male patient (58 years of age) with metastasis of a colon carcinoma in the abdominal cavity and wall showed a sudden hyperecho, from obvious attenuation in the posterior part of the target tumor and disappearance of the tumor boundary in real-time US. We stopped HIFU treatment immediately. Subsequently, the patient was found febrile with a body temperature continuously rising to a climax of 39.2°C one day after HIFU and had other symptoms typical of acute peritonitis. An emergent exploration was conducted and a diameter of 1.5 cm perforation in the terminal ileum was found.

As a local non-invasive treatment for solid tumor ablation, and with characteristics of directivity and focalization, HIFU can transfer energy to target tissues, resulting in ablation. The US wave is partially converted into heat, making the focal temperature rise to over 90°C[22]. This thermal effect induces tissue and vessel damage by coagulative necrosis. Because the temperature increases quickly and swiftly, it is almost totally transferred to the targeted tissue. Recently, there have been many clinical studies using HIFU for alleviation of solid tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, osteocarcinoma, etc[7,22]. HIFU has been thought to be a generally noninvasive and safe modality for solid tumors.

However, there is some inevitable heat diffusion out of the focal region which can damage the surrounding tissues. Cavitation can also cause destruction of targeted and surrounding tissue. Due to the negative part of the US, intracellular water may enter the gaseous phase, leading to the development of micro-bubbles. When these bubbles reach the size of resonance, they suddenly collapse and produce high-pressure shock waves, destroying adjacent tissue[23,24]. Furthermore, due to other bio-effects of focused ultrasound, such as heat deposition by reflection and deflection of scattered ultrasound radiation, there must be some complications in surrounding and overlying tissues. Also, because of differences in heat sensitivity, as well as energy deposition between these target and adjacent tissues or organs, there are different side effects or complications in different tissues or organs resulting from HIFU treatment.

Other local factors also contribute to complications of HIFU treatment for recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors. First, the reflection of ultrasound caused by ribs and other bones can deposit ultrasonic energy in skin and subcutaneous layers, resulting in skin burns, especially when targeting tumors in the upper abdomen and pelvic cavity by HIFU. Secondly, absorption of ultrasonic energy by HIFU can damage tissues in the pathway of HIFU, and hurt the adjacent tissues. Next, difference in acoustic impedance (e.g. between gastric-intestinal tract, target tumor and air) can result in different distribution of energy into tissues and cause damage to the tissue in the interface. Also, recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors often have been subjected to prior multiple treatments such as surgery which causes changes in anatomy; these tumors are large and anomalous, without definite boundaries. Gastrointestinal motility easily causes dislocation of the targeting volume during HIFU; US also has some limitations in real-time monitoring the temperature of the focal region and cavitation disturbs judgment about the ablation region and may result in too much ultrasonic energy being transferred to the target volume and surrounding tissues. These factors may result in more complications in patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors in our study than in other studies.

The following are the detailed complications according to different classification.

Thermal injury: this was the most common complication due to ultrasonic energy deposition in the pathway of ultrasound, including skin and subcutaneous burns, and muscle heat injury. Thermal injury caused by ultrasonic reflection: these complications usually happen in the interface between tissues with drastic acoustic impedance, which results in strong energy absorption. Therefore, these traumas are located in the interfaces either between air and skin, or between air and the gastrointestinal tract. The bladder and skin on the opposite side were also involved.

Trauma in adjacent tissues or organs: these complications include damage of right renal function, hematuria, enteroparalysis, etc. Impairments in thermal-sensitive tissue: nervous tissue hurt in HIFU presents as local numbness in skin.

Systemic reactions of thermotherapy owed to ultrasound: these include fever during and post HIFU treatment, elevation of blood creatinine, hypertension, etc.

In our study, skin burns were found in all 17 patients. These skin burns differed in intensity; those with first and second degree skin burns and soon recovered without special treatments. In contrast, one patient suffered from a deep skin burn (third grade) after HIFU, and needed immediate surgery for full-thickness resection and suture.

Other systemic and local complications were relatively rare, which were traumas of surrounding and overlying tissues or organs. The majority of patients usually needed no further special handling beyond accepted medical observation and symptomatic treatment.

Unfortunately, there were two severe complications including superior mesentery arterial infarction and perforation of the terminal ileum. In a retrospectively analysis, the former patient had a large tumor in the upper abdomen with an irregular boundary, and the superior mesentery artery (SMA) running out from the center of tumor as seen by CT and MRI before HIFU. A coagulatively necrotic and hardened target tumor induced by HIFU may decrease arterial compliance which results in lowering blood supply to the small intestine; edema in the peritumor tissues also aggravate the compression to the SMA and can cause infarction and necrosis of the entire small intestines. The latter patient with metastatic tumors in the abdominal cavity and wall had perforation in the terminal ileum due to HIFU treatment. The possible cause for this complication was that the target tumor was close to the terminal ileum which was full of fluid and little air, these may result in difficult discrimination between target tumor and ileum, and further causing imprecise positioning of real-time US during HIFU. These may have induced emission of the focused ultrasound into the ileac wall directly and resulted in a perforation.

Though HIFU is a noninvasive treatment for patients with recurrent and metastatic abdominal tumors, there are some common and severe complications. Sufficient preoperative imaging, partial coverage of the target tumor for evading gut trauma with HIFU, clinical investigations for changes of gut after HIFU, and even early exploratory laparotomy for acute abdomen symptoms are all needed in support of HIFU treatment.

The authors sincerely thank Professor Feng Wu, Professor Wen-zhi Chen and Professor Jian-zhong Zou from the 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University for their kindness and academic support.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Gambelunghe G, Fatone C, Ranchelli A, Fanelli C, Lucidi P, Cavaliere A, Avenia N, d'Ajello M, Santeusanio F, De Feo P. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of ultrasound-guided laser photocoagulation for treatment of benign thyroid nodules. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:RC23-RC26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Silverman SG, Tuncali K, Morrison PR. MR Imaging-guided percutaneous tumor ablation. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1100-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Harrod-Kim P. Tumor ablation with photodynamic therapy: introduction to mechanism and clinical applications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1441-1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Palumbo G. Photodynamic therapy and cancer: a brief sightseeing tour. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:131-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carey B, Swift S. The current role of imaging for prostate brachytherapy. Cancer Imaging. 2007;7:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kennedy JE, Ter Haar GR, Cranston D. High intensity focused ultrasound: surgery of the future. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:590-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 555] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu F, Wang ZB, Chen WZ, Wang W, Gui Y, Zhang M, Zheng G, Zhou Y, Xu G, Li M. Extracorporeal high intensity focused ultrasound ablation in the treatment of 1038 patients with solid carcinomas in China: an overview. Ultrason Sonochem. 2004;11:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang ZB, Wu F, Wang ZL, Zhang Z, Zou JZ, Liu C, Liu YG, Cheng G, Du YH, He ZC. Targeted damage effects of high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) on liver tissues of Guizhou Province miniswine. Ultrason Sonochem. 1997;4:181-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Burgess SE, Iwamoto T, Coleman DJ, Lizzi FL, Driller J, Rosado A. Histologic changes in porcine eyes treated with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987;19:133-138. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Yang R, Reilly CR, Rescorla FJ, Faught PR, Sanghvi NT, Fry FJ, Franklin TD, Lumeng L, Grosfeld JL. High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of experimental liver cancer. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1002-1009; discussion 1009 -1010;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | ter Haar G. High intensity ultrasound. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:77-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Prat F, Centarti M, Sibille A, Abou el Fadil FA, Henry L, Chapelon JY, Cathignol D. Extracorporeal high-intensity focused ultrasound for VX2 liver tumors in the rabbit. Hepatology. 1995;21:832-836. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chen L, Rivens I, ter Haar G, Riddler S, Hill CR, Bensted JP. Histological changes in rat liver tumours treated with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1993;19:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leslie TA, Kennedy JE. High-intensity focused ultrasound principles, current uses, and potential for the future. Ultrasound Q. 2006;22:263-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adams JB, Moore RG, Anderson JH, Strandberg JD, Marshall FF, Davoussi LR. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation of rabbit kidney tumors. J Endourol. 1996;10:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chapelon JY, Margonari J, Theillère Y, Gorry F, Vernier F, Blanc E, Gelet A. Effects of high-energy focused ultrasound on kidney tissue in the rat and the dog. Eur Urol. 1992;22:147-152. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Chen W, Wang Z, Wu F, Bai J, Zhu H, Zou J, Li K, Xie F, Wang Z. High intensity focused ultrasound alone for malignant solid tumors. Zhonghua ZhongLiu ZaZhi. 2002;24:278-281. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Foster RS, Bihrle R, Sanghvi NT, Fry FJ, Donohue JP. High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of prostatic disease. Eur Urol. 1993;23 Suppl 1:29-33. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kincaide LF, Sanghvi NT, Cummings O, Bihrle R, Foster RS, Zaitsev A, Phillips M, Syrus J, Hennige C. Noninvasive ultrasonic subtotal ablation of the prostate in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1225-1227. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chaussy C, Thüroff S. High-intensity focused ultrasound in prostate cancer: results after 3 years. Mol Urol. 2000;4:179-182. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Wu F, Wang ZB, Zhu H, Chen WZ, Zou JZ, Bai J, Li KQ, Jin CB, Xie FL, Su HB. Feasibility of US-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;236:1034-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu F, Wang ZB, Chen WZ, Zou JZ, Bai J, Zhu H, Li KQ, Jin CB, Xie FL, Su HB. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation combined with transcatheter arterial embolization. Radiology. 2005;235:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yu T, Fan X, Xiong S, Hu K, Wang Z. Microbubbles assist goat liver ablation by high intensity focused ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1557-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rabkin BA, Zderic V, Crum LA, Vaezy S. Biological and physical mechanisms of HIFU-induced hyperecho in ultrasound images. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1721-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |