Published online May 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2427

Revised: December 28, 2006

Accepted: February 12, 2007

Published online: May 7, 2007

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In man, the pathobiological changes associated with HCV infection have been attributed to both the immune system and direct viral cytopathic effects. Until now, the lack of simple culture systems to infect and propagate the virus has hampered progress in understanding the viral life cycle and pathogenesis of HCV infection, including the molecular mechanisms implicated in HCV-induced HCC. This clearly demonstrates the need to develop small animal models for the study of HCV-associated pathogenesis. This review describes and discusses the development of new HCV animal models to study viral infection and investigate the direct effects of viral protein expression on liver disease.

- Citation: Kremsdorf D, Brezillon N. New animal models for hepatitis C viral infection and pathogenesis studies. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(17): 2427-2435

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i17/2427.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2427

Despite the fact that infectious diseases account for at least one-third of all deaths worldwide, our capacity to study both their pathophysiology and host immune responses in man is often limited by the lack of simple laboratory models of infection. During the past decade, laboratory animals have been used as models of human diseases. In particular, transgenic mice models have been helpful to the understanding of the molecular basis of human diseases. The story of hepatitis C virus (HCV) started in the 1970s with the emergence of patients suffering from hepatitis syndrome which was not associated to hepatitis A or B infection (HAV or HBV). This new agent was named NANBH, for non-A non-B hepatitis[1]. In 1978, Alter et al[2] demonstrated that the inoculation of NANBH human sera in chimpanzees induced liver disease, and in 1989 Choo et al[3] identified a third viral agent for hepatitis by cloning a non-simian cDNA from the serum of a NANBH-infected chimpanzee. HCV infection leads to liver cirrhosis in up to 35% of cases and hepatocellular carcinoma develops in 2%-7% of cirrhotic patients per year. It is now accepted that the pathobiological changes induced by HCV infection are due to both the immune response and the direct viral cytopathic effects of the virus. As described by other authors in this issue, there is no prophylactic vaccine against HCV at present, and the therapeutic options are mainly limited by a lack of effective long-term treatment. Like other human hepatitis viruses, HCV needs fully functional human hepatocytes for its development. The discovery of anti-infectious agents and immune defense mechanisms has to date been severely restricted by the ethical and practical constraints of access to receptive cells. Due to the nearly strict human tropism of HCV, only man and higher primates such as chimpanzees have until recently been receptive to HCV infection and development. The purpose of this review is to focus on new HCV animal models independent of the chimpanzee, which will enable the study of viral infection and the direct effects of viral protein expression on liver disease.

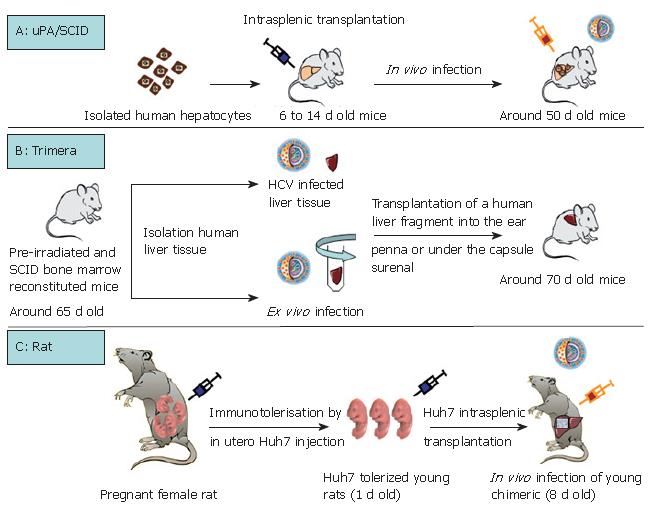

As summarized in Table 1, except for the chimpanzee, the only non-human primate permissive to HCV infection is the marmoset. Tupaia, a member of the Tree shrew genus is equally infected by HCV. The capacity for GBV-B, a hepatotrope virus of the flaviviridae family, to infect tamarins and marmosets has been used as a tool to better characterize HCV virus replication and to test HCV antiviral drugs[4-6]. However, none of these models is perfect, particularly because of their inability to produce numerous animals in a short time (long gestation periods) and their high breeding costs. Rodents are certainly the most appropriate model for all biological studies. Their short gestation period (around 20 d for mice and rats), their small size and their low cost are particularly advantageous. Three interesting models for HCV infection: the immunotolerized rat model, the Trimera mouse model and the uPA/SCID model, are being developed (Table 2, Figure 1).

| Virus | Animal tested | Infection | Original reference | |

| HCV | Non human primates | Chimpanzee | Yes | Alter et al[2] 1978 |

| Marmoset | Yes | Feinstone et al[71] 1981 | ||

| Cottontop tamarin | No | Garson et al[72] 1997 | ||

| Cynomoglus monkey | No | |||

| Rhesus monkey | No | |||

| Green monkey | No | |||

| Japanese monkey | No | Abe et al[73] 1993 | ||

| Doguera baboon | No | |||

| Chacma baboon | No | Sithebe et al[74] 2002 | ||

| Scandentia | Tupaia | Yes | Xie et al[75] 1998 | |

| Rodents | uPA/SCID mice | Yes | Mercer et al[26] 2001 | |

| Trimera mice | Yes | Galun et al[10] 1995 | ||

| Rat | Yes | Wu et al[8] 2005 | ||

| Woodchuck | No | Abe et al[73] 1993 | ||

| Rodent models | Humanization | Viremia | Duration of viral infection | Comments | Publications |

| uPA/SCID mice | Human hepatocyte transplantation | 1 × 104 to 8 × 107 copies/mL | Up to 9 mo with maximum viremia as from one month | High viremia | |

| Variability of primary human hepatocytes | Mercer et al[26] 2001 | ||||

| Meuleman et al[22] 2005 | |||||

| Immunosuppressed mice | Kneteman et al[29] 2006 | ||||

| Trimera mice | Xenograft of human liver tissue | Around 7 × 104 copies/mL | Around one month with peak viremia at 18 d | Low viremia | |

| Variability of human liver tissues | Ilan et al[12] 2002 | ||||

| Immunosuppressed mice | Eren et al[11] 2006 | ||||

| Rat | Immunotolerization and transplantation of a human hepatoma cell line | 1-2 × 104 copies/mL | Minimum 4 mo with peak viremia at 3 mo | Low viremia | |

| Transplantation of a hepatoma cell line | Wu et al[8] 2005 | ||||

| Immunocompetent rat |

Interestingly, Wu et al took account of the fact that the rat immune system does not develop until 15-17 d of gestation. They immunotolerized rat embryos to allow the transplantation and maintenance of a human hepatoma cell line (Huh7)[7] which could be infected with HCV[8] (Table 2, Figure 1C). Briefly, fetal rats are tolerized by an intraperitoneal injection of Huh7 cells into pregnant females at the 17th d of gestation. Twenty-four hours after birth, the rats are intrasplenically transplanted with the same hepatoma cell line which will represent around 6% of total hepatocytes after 14 d of development. Nearly 30% of the transplanted human hepatocytes are positive for HCV core protein after inoculation with HCV (genotype 1) positive human serum (Figure 1C). This new animal model is promising but validation remains necessary, for example by using this model to confirm the antiviral effects of drugs used for anti-HCV therapy in humans.

The Trimera mouse model involves the development of a chimeric mouse with a different source of tissue[9,10]. BNX (beige/nude/X-linked immunodeficient) mice are preconditioned by total body irradiation and reconstituted with SCID mouse bone marrow. These mice tolerate the transplantation of HCV-infected liver fragments from patients with HCV RNA-positive sera, as well as the transplantation of an ex vivo HCV-infected liver fragment[10-12]. The liver fragment is transplanted into the ear pinna or under the kidney capsule. In this way, the transplant can be maintained for several weeks and HCV messengers were detected in the serum for up to one month (Table 2, Figure 1B)[10-12]. The model has been validated as a tool for the testing of antiviral components. During a first set of experiments, an inhibitor of the internal ribosomal entry site and an anti-HCV monoclonal antibody were demonstrated to act as potential HCV inhibitors[12]. Recently, the same team produced and characterized two monoclonal antibodies directed against HCV envelope protein E2. Following in vitro validation of the ability of these antibodies to immunoprecipitate HCV particles, they confirmed an inhibitory effect on HCV infection[11]. Indeed, in the HCV-Trimera model, both monoclonal E2 antibodies were shown to be capable of inhibiting the ex vivo HCV infection of human liver fragments (reduction of resultant viremia from 3 × 104 to 3 × 103 copies/mL). A reduction in viremia (3.1 × 104 to 5 × 103 copies/mL) was also demonstrated when these antibodies were used to treat HCV-trimera mice[11]. In conclusion, this mouse model appears to be well-suited to evaluating the inhibitory capacity of drugs, as had previously been shown with monoclonal antibodies directed against HBV[13,14]. Nevertheless, we should not forget that this approach involves the use of heterotopic and xenogenic grafts, so that we can never be entirely sure of the physiological relevance of observations.

Historically, urokinase plasminogen uPA transgenic mice were described in 1990 by Heckel et al[15]. The same team then demonstrated the ability of a small number of "normal" hepatocytes to repopulate ad-integrum the liver of transgenic uPA mice[16]. Indeed, the overexpression of uPA protein in hepatocytes is cytotoxic, giving rise to a continuous liver regeneration process. Under these condi-tions, hepatocytes which lose the transgene by somatic reversion, as well as healthy transplanted hepatocytes, have a strong survival advantage over resident cells[16,17]. Based on this advantage, uPA transgenic mice were back-crossed on an immunodeficient background (SCID or Rag2 mice) to obtain a mouse model which tolerated the xenotransplantation of human, woodchuck and tupaia hepatocytes[17-22]. Optimum liver repopulation requires the intrasplenic transplantation, within one or two weeks of birth, of high quality hepatocytes into mice which are homozygous for both the SCID trait and uPA transgene (Table 2, Figure 1A). The morphological and biochemical characterization of chimeric mice revealed satisfactory hepatic architecture and fusion of the mouse and human structures, indicating a physiological integration of trans-planted cells[20,22]. The functionality of transplanted hepa-tocytes was attested by their susceptibility to infection with human hepatotropic pathogens such as Plasmodium falciparum[23], hepatitis B virus[22,24,25] and hepatitis C virus[22,26-28]. It was subsequently shown that this HCV-in-fected humanized mouse could be used to demonstrate the antiviral activity of two compounds which had already been shown to be effective during clinical trials: the ad-ministration in mice of IFNα2b and an anti protease agent (BILN-2061) significantly reduced HCV viremia[29]. Furthermore, it was shown that the antiviral effect was dependent on the viral genotype but appeared to be in-dependent of the provenance of human hepatocytes. Interestingly, another team confirmed the antiviral effect of BILN-2061, but they also encountered cardiotoxic adverse effects with this compound (unpublished data, ISVHLD 2006 congress, Vanwolleghem et al). The uPA/SCID model is therefore appropriate for testing new anti-viral molecules by evaluating their efficacy and toxicity.

It is clear that the immune response to viral infection plays a major role in the outcome of liver disease. By taking advantage of the absence of adaptive immune response in the chimeric uPA/SCID mouse model, Walters et al[30] were able to investigate the role of the innate antiviral immune response to HCV infection. The purpose of their study was to distinguish virus-induced gene expression changes from adaptive HCV-specific immune-mediated effects. Globally, in the uPA/SCID mouse model, HCV infection activates the transcription of interferon-stimulated genes which are in particular implicated in establishing the innate immune response, and thus active in the inhibition of HCV replication. As previously shown in HCV-infected patients and HCV transgenic mice, these authors confirmed in the uPA/SCID mouse model the relationship between a severe HCV infection and lipid metabolism perturbation, suggesting that liver disease may not be mediated exclusively by an HCV-specific adaptive immune response. Thus, the innate immune response may play a fundamental role in limiting the viral HCV RNA copy number and can thus slow the progression of infection.

In summary, the recent development of small animal models for experimental HCV infection has opened new perspectives for the evaluation of novel therapeutic and/or prophylactic compounds against HCV. Indeed, these three rodent models are really promising, although relatively complicated to use, but they present the un-questionable advantage of being much less expensive and easier to maintain and breed than primates. The rat model may be the most accessible, notably because of the immunocompetent nature of the animals and the larger number of reproducible infected animals that could be obtained in theory using hepatocyte cell line transplantation. The two mice models are more physiologically relevant, in that they are based on the transplantation of human tissue or primary hepatocytes. The model most closely related physiologically to humans is certainly the uPA/SCID mouse. Indeed, even if this model is developed in an immunotolerant setting, humanized liver may contain around 75% of human hepatocytes as compared to just 6% of hepatoma cells in the rat (Table 2). Furthermore, viremia clearly lasts longer and at higher levels in uPA/SCID mice than in other models (Table 2). Under these conditions, the uPA/SCID mouse model appears to be the most relevant to building a bridge between in vitro research and clinical trials.

HCV TRANSGENIC MOUSE MODELS

An increasing body of evidence suggests a direct in-volvement of HCV in cellular metabolic disturbances. As described in this report, conditional expression of the HCV genome in transgenic mice has enabled study of the direct effect of HCV on hepatocytes, and investigation of the molecular pathways of HCV associated with liver injury. This has generated data crucial to our understanding of several aspects of HCV pathogenesis. As reported in Table 3, and despite some contradictory results, the development of HCV transgenic mouse models has enabled evaluation of the different, direct cytopathic effects of HCV protein and their correlation with the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C.

| Viral protein | Original reference of the transgenic mouse | Mouse strain | Promoter | Comments | References |

| Core | Moriya et al[42] 1997 | C57BL/6 | HBV | Steatosis | Moriya et al[40] 1998 |

| HCC | Moriya et al[42] 1997 | ||||

| Oxidative stress | Moriya et al[41] 2001 | ||||

| Increased concentration of monounsaturated fatty acids | Moriya et al[37] 2001 | ||||

| Inhibition of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein activity and VLDL secretion. | Perlemuter et al[38] 2002 | ||||

| Alcohol and core protein increase lipid peroxidation | Perlemuter et al[39] 2003 | ||||

| Alteration of intrahepatic cytokine expression and AP-1 activation | Tsutsumi et al[45] 2002 | ||||

| Interaction with retinoid X receptor alpha | Tsutsumi et al[43] 2002 | ||||

| Cooperation with ethanol activation of MAPK | Tsutsumi et al[44] 2003 | ||||

| Insulin resistance | Shintani et al[34] 2004 | ||||

| Koike et al[33] 2006 | |||||

| Modulation of interferon pathway (Inhibition of SOCS-1 expression) | Miyoshi et al[47] 2005 | ||||

| ER stress, apoptosis | Benali-Furet et al[78] 2005 | ||||

| Core | Honda et al[52] 2000 | C57BL/6 | HBV | Modulated sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis | Honda et al[52] 2000 |

| Insulin resistance via down-regulation hepatic IRS1 and 2 | Kawaguchi et al[35] 2004 | ||||

| Constitutive activation of STAT3, implication in HCC | Yoshida et al[46] 2002 | ||||

| Core | Pasquinelli et al[50] 1997 | C57BL/6 | Major urinary protein | No liver disease | Pasquinelli et al[50] 1997 |

| Core (Korean wt and mutants) | Wang et al[79] 2004 | C57BL/6J | HBV | Cell dysplasia for S99Q core mutant | Wang et al[79] 2004 |

| Core (in T cell) | Soguero et al[53] 2002 | C57BL/6 | CD2 | Increased Fas-mediated apoptosis and liver infiltration of peripheral T cells | Soguero et al[53] 2002 |

| Double Tg core X TCR | Cruise et al[55] 2005 | C57BL/6 × DO11.10 (H-2d) | Increased Fas ligand expression of CD4+ T cells associated with liver inflammation | Cruise et al[55] 2005 | |

| Role of CXCR3 ligands via Fas induction, during the inflammatory response | Cruise et al[54] 2006 | ||||

| Core | Ishikawa et al[48] 2003 | C57BL/6N | serum amyloid | Malignant lymphoma and Hepatocellular adenoma in old mice | Ishikawa et al[48] 2003 |

| Core | Kato et al[49] 2003 | C57BL/6 | serum amyloid P | Adenoma and HCC development in transgenic mice following repeated CCl4 administrations. | Kato et al[49] 2003 |

| Core Core-E1-E2 | Kamegaya et al[51] 2005 | FVB × C57BL/6 | Albumin | After DEN treatment, core-E1-E2 mice develop tumors with a larger size than core mice (diminution of apoptotic index) | Kamegaya et al[51] 2005 |

| Core-E1-E2-p7 | Lerat et al[62] 2002 | C57BL/6 | Albumin | Steatosis | Lerat et al[62] 2002 |

| HCC (rare) | |||||

| Sensitivity to oxidative stress | Okuda et al[80] 2002 | ||||

| Core-E1-E2-p7 | Korenaga et al[81] 2005 | C57BL/6J | Albumin | Increase in ROS production by mitochondrial electron transport complex I | Korenaga et al[81] 2005 |

| Core-E1-E2 | Kawamura et al[82] 1997 | FVB | Albumin or major urinary protein | No liver disease | Kawamura et al[82] 1997 |

| Core-E1-E2 | Honda et al[56] 1999 | C57BL/6 | H2-Kd | Sensitivity to anti-fas administration | Honda et al[56] 1999 |

| Core-E1-E2 | Naas et al[57] 2005 | C57BL/6 | CMV | Steatosis. | Naas et al[57] 2005 |

| Acceleration of liver and lymphoid tumor development | |||||

| Core-E1-E2-NS2 | Wakita et al[59] 1998 | Balb/C | Cre/Lox system (CAG promoter) | Hepatitis injury associated with HCV-specific CTL response | Wakita et al[59] 1998 Wakita et al[58] 2000 |

| Suppression of Fas-mediated cell death | Machida et al[83] 2001 | ||||

| HCV-specific CD8+ CTLs specifically induce liver injury | Takaku et al[62] 2003 | ||||

| E1-E2 | Koike et al[63] 1995 | CD1 | HBV | No liver disease | Koike et al[63] 1995 |

| Expression in salivary glands | |||||

| Exocrinopathy resembling Sjogren syndrome | Koike et al[84] 1997 | ||||

| E2 | Pasquinelli et al[50] 1997 | C57BL/6 | Albumin | No liver disease | Pasquinelli et al[50] 1997 |

| NS3-NS4A | Frelin et al[64] 2006 | C57BL/6 | Major urinary protein | No liver disease. | Frelin et al[64] 2006 |

| Alteration of hepatic immune cell subsets. | |||||

| Reduced sensitivity to TNF alpha mediated liver disease. | |||||

| NS5 | Majumder et al[65] 2002 | FVB | ApoE | No liver disease | Majumder et al[65] 2002 |

| Protection against TNF alpha mediated liver disease (inhibition of NF-kappaB activation) | Majumder et al[66] 2003 | ||||

| Full polyprotein | Alonzi et al[60] 2004 | C57BL/6 | Alpha1 antitrypsin | Steatosis | Alonzi et al[60] 2004 |

| Blindenbacher et al[67] 2003 | T cell infiltrate | ||||

| Inhibition of IFN alpha-induced signaling | Blindenbacher et al[67] 2003 | ||||

| Increased expression of protein phosphatase 2A | Duong et al[68] 2004 | ||||

| Full polyprotein | Lerat et al[62] 2002 | C57BL/6 | Albumin | Hepatic steatosis, HCC | Lerat et al[62] 2002 |

| Impairment of intrahepatic immune response (absence of elimination of adenovirus-infected hepatocytes) | Disson et al[85] 2004 | ||||

| Down-regulation of pro-apoptotic CIDE-B protein in adenovirus-infected transgenic mice | Erdtmann et al[86] 2003 | ||||

| Iron overload induces increase the risk of HCC (mitochondrial injury) | Furutani et al[87] 2006 |

Recently, a correlation between HCV infection and both diabetes and insulin resistance was suggested, indicating that they might be metabolic diseases associated with viral infection[31,32]; this could be a critical factor in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C. Transgenic mouse models have demonstrated a link between HCV core protein expression and elevated serum insulin levels, associated with a minor elevation of plasmatic glucose but without the development of diabetes[33,34]. Furthermore, the administration of insulin resulted in higher glycemia when compared to values in non-transgenic mice, indicating the presence of an insulin resistance phenotype in core transgenic mice[33,34]. This insulin resistance may be due to down-regulation in the expression of insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 (IRS1 and 2), probably via an up-regulation of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3)[35]. One possible mechanism is that HCV core-induced SOCS3 promotes the proteosomal degradation of IRS1 and IRS2 through ubiquitination[35]. These results therefore provide direct experimental evidence for a role of HCV core protein in the development of insulin resistance mechanisms in HCV-infected patients.

Hepatic steatosis, which involves an accumulation of intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, is a common histological feature which is observed in more than 50% of chronic hepatitis C carriers[36]. Both host and viral factors have been demonstrated to play an important role in its development. By accelerating the development of fibrosis, steatosis may contribute to the progression of liver disease and the development of HCC. Consistent with the implication of viral protein in steatosis, it has been reported that the core protein of HCV targets microsomal triglyce-ride transfer protein activity, modifies hepatic VLDL assembly and secretion and increases the concentration of monosaturated fatty acids[37,38]. Furthermore, alcohol consumption in core transgenic mice has been shown to increase hepatic lipid peroxidation and hepatic TNF alpha and TGF beta expression[39]. This may participate in activating fibrogenesis and hence the development of HCC observed in HCV patients who abuse alcohol.

Epidemiological evidence favors a direct role for HCV in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Despite some contradictory results, transgenic mouse models have demonstrated the implication of core protein expression in HCC development. Moriya et al[40-42] showed that core protein expression in mice led to steatosis, oxidative stress and ultimately HCC in aging mice. RXR alpha is activated by cellular retinol binding protein II (CRBP II) in the liver of core-expressing transgenic mice[43]; sug-gesting that the modulation of RXR alpha-controlled gene expression via its interaction with core protein could contribute to liver pathogenesis. Alterations to other signaling pathways via activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), activator protein-1 (AP-1), MAPK and the suppression of SOCS-1 expression may equally contribute to tumorigenesis in HCV core-expressing transgenic mice[44-47]. In another core transgenic line, the development of malignant lymphoma and hepatocellular adenoma has been observed[48]. In other reports, neither steatosis nor hepatic tumors were detected in core transgenic mice[49,50]. However, HCC was more frequently observed after diethylnitrosamine treatment or the repeated administration of carbon tetrachloride[49,51].

HCV-core protein in liver cells may affect the persistence of Fas-mediated liver cell injury[52]. Liver inflammation induced by HCV core-expression in CD4+ T cells is associated with high expression levels of the Fas ligand and CXCR3 chemokine induction[53-55]. In this context, liver inflammation is abolished by anti-Fas antibody treatment[54,55]. Similarly, transgenic mice expressing Core-E1-E2 present with hepatocyte necrosis associated with increased Fas-mediated injury[56,57]. Furthermore, the expression of core-E1-E2-NS2 viral proteins, as well as of the entire HCV polyprotein, may induce steatosis with lymphocyte cell infiltrate, mito-chondrial injury and sensitivity to oxidative stress and HCC in aging animals[58-62]. By contrast, E1-E2, E2, NS3-NS4A or NS5A transgenic animals have not been shown to exhibit any major histological changes to the liver[50,63-66].

In vivo experiments in transgenic mice have confirmed that the expression of full HCV polyproteins and core protein inhibits interferon alpha signaling. The HCV core protein has been shown to induce an aberrant expression of SOCS1, which can suppress Jak-STAT signaling activation[47]. Similarly, STAT signaling was found to be strongly inhibited in the liver of HCV transgenic mice[67]. In this model, STAT phosphorylation by Jak was not reduced, but the binding of STAT transcription factors to the promoters of interferon-stimulated genes was inhibited[67]. HCV expression in the liver is associated with the inhibition of STAT function by concomitant induction of the expression of the protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIAS)[68]. This may be mediated via an up-regulation of protein phosphatase 2A and by STAT demethylation[68,69]. In addition, NS5 protein activates STAT3 through interaction with Jak1[70].

In summary, and despite some discordant data, studies involving transgenic mice expressing one or a combination of HCV viral proteins have been essential to a clearer understanding of the mechanisms involved in HCV-induced pathogenesis. However, to be rigorous the interpretation of any data must take account of variations in the genetic background of mice, constitutive transgene expression and the absence of any immune response. Nevertheless, even if we consider the variability of morphological observations and the diversity of biochemical data, most reports strongly support a direct role for core protein in liver pathogenesis. Core protein may predispose subjects to HCC development through its contribution to the onset of steatosis, fibrosis and oxidative stress, particularly by acting on the expression of cell growth-related genes, the interferon pathway and lipid metabolism.

This review underlines the usefulness of rodent models in the field of HCV infection studies. Indeed, as pointed out, exponential information has been obtained using small animal models which are susceptible to HCV infection or allow HCV protein expression. The principal advance in this area is the establishment of small animal models which can support the entire life cycle of the virus. However, the contribution of different viral proteins to HCV-related pathogenesis is far from being clarified. Indeed, if we are to reach definite conclusions regarding the mechanisms linked to HCV pathogenesis, the next step must be to develop a rodent model which can harbor both a human immune system and human liver cells susceptible to HCV infection. This rodent model will constitute a new tool to allow the efficient screening of HCV vaccine candidates. Finally, without forgetting the indispensable role of the chimpanzee (which remains the optimum model to study the efficacy of future vaccines), new animal models such as transgenic mice and HCV infection-permissive rodents constitute extremely promising and complementary tools which will enable us to better understand and fight against HCV infection.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Hennenberg M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Feinstone SM, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH, Alter HJ, Holland PV. Transfusion-associated hepatitis not due to viral hepatitis type A or B. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:767-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Holland PV, Popper H. Transmissible agent in non-A, non-B hepatitis. Lancet. 1978;1:459-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4996] [Cited by in RCA: 4657] [Article Influence: 129.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bright H, Carroll AR, Watts PA, Fenton RJ. Development of a GB virus B marmoset model and its validation with a novel series of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease inhibitors. J Virol. 2004;78:2062-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nam JH, Faulk K, Engle RE, Govindarajan S, St Claire M, Bukh J. In vivo analysis of the 3' untranslated region of GB virus B after in vitro mutagenesis of an infectious cDNA clone: persistent infection in a transfected tamarin. J Virol. 2004;78:9389-9399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rijnbrand R, Yang Y, Beales L, Bodola F, Goettge K, Cohen L, Lanford RE, Lemon SM, Martin A. A chimeric GB virus B with 5' nontranslated RNA sequence from hepatitis C virus causes hepatitis in tamarins. Hepatology. 2005;41:986-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ouyang EC, Wu CH, Walton C, Promrat K, Wu GY. Transplantation of human hepatocytes into tolerized genetically immunocompetent rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:324-330. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wu GY, Konishi M, Walton CM, Olive D, Hayashi K, Wu CH. A novel immunocompetent rat model of HCV infection and hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1416-1423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lubin I, Faktorowich Y, Lapidot T, Gan Y, Eshhar Z, Gazit E, Levite M, Reisner Y. Engraftment and development of human T and B cells in mice after bone marrow transplantation. Science. 1991;252:427-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galun E, Burakova T, Ketzinel M, Lubin I, Shezen E, Kahana Y, Eid A, Ilan Y, Rivkind A, Pizov G. Hepatitis C virus viremia in SCID--& gt; BNX mouse chimera. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eren R, Landstein D, Terkieltaub D, Nussbaum O, Zauberman A, Ben-Porath J, Gopher J, Buchnick R, Kovjazin R, Rosenthal-Galili Z. Preclinical evaluation of two neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against hepatitis C virus (HCV): a potential treatment to prevent HCV reinfection in liver transplant patients. J Virol. 2006;80:2654-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ilan E, Arazi J, Nussbaum O, Zauberman A, Eren R, Lubin I, Neville L, Ben-Moshe O, Kischitzky A, Litchi A. The hepatitis C virus (HCV)-Trimera mouse: a model for evaluation of agents against HCV. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:153-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eren R, Ilan E, Nussbaum O, Lubin I, Terkieltaub D, Arazi Y, Ben-Moshe O, Kitchinzky A, Berr S, Gopher J. Preclinical evaluation of two human anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) monoclonal antibodies in the HBV-trimera mouse model and in HBV chronic carrier chimpanzees. Hepatology. 2000;32:588-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Galun E, Eren R, Safadi R, Ashour Y, Terrault N, Keeffe EB, Matot E, Mizrachi S, Terkieltaub D, Zohar M. Clinical evaluation (phase I) of a combination of two human monoclonal antibodies to HBV: safety and antiviral properties. Hepatology. 2002;35:673-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Heckel JL, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Neonatal bleeding in transgenic mice expressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Cell. 1990;62:447-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sandgren EP, Palmiter RD, Heckel JL, Daugherty CC, Brinster RL, Degen JL. Complete hepatic regeneration after somatic deletion of an albumin-plasminogen activator transgene. Cell. 1991;66:245-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rhim JA, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Replacement of diseased mouse liver by hepatic cell transplantation. Science. 1994;263:1149-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Petersen J, Dandri M, Gupta S, Rogler CE. Liver repopulation with xenogenic hepatocytes in B and T cell-deficient mice leads to chronic hepadnavirus infection and clonal growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:310-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dandri M, Burda MR, Gocht A, Török E, Pollok JM, Rogler CE, Will H, Petersen J. Woodchuck hepatocytes remain permissive for hepadnavirus infection and mouse liver repopulation after cryopreservation. Hepatology. 2001;34:824-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tateno C, Yoshizane Y, Saito N, Kataoka M, Utoh R, Yamasaki C, Tachibana A, Soeno Y, Asahina K, Hino H. Near completely humanized liver in mice shows human-type metabolic responses to drugs. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:901-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dandri M, Burda MR, Zuckerman DM, Wursthorn K, Matschl U, Pollok JM, Rogiers X, Gocht A, Köck J, Blum HE. Chronic infection with hepatitis B viruses and antiviral drug evaluation in uPA mice after liver repopulation with tupaia hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2005;42:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, De Vos R, de Hemptinne B, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Roskams T, Leroux-Roels G. Morphological and biochemical characterization of a human liver in a uPA-SCID mouse chimera. Hepatology. 2005;41:847-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Morosan S, Hez-Deroubaix S, Lunel F, Renia L, Giannini C, Van Rooijen N, Battaglia S, Blanc C, Eling W, Sauerwein R. Liver-stage development of Plasmodium falciparum, in a humanized mouse model. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:996-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dandri M, Burda MR, Török E, Pollok JM, Iwanska A, Sommer G, Rogiers X, Rogler CE, Gupta S, Will H. Repopulation of mouse liver with human hepatocytes and in vivo infection with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2001;33:981-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsuge M, Hiraga N, Takaishi H, Noguchi C, Oga H, Imamura M, Takahashi S, Iwao E, Fujimoto Y, Ochi H. Infection of human hepatocyte chimeric mouse with genetically engineered hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2005;42:1046-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mercer DF, Schiller DE, Elliott JF, Douglas DN, Hao C, Rinfret A, Addison WR, Fischer KP, Churchill TA, Lakey JR. Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat Med. 2001;7:927-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 693] [Cited by in RCA: 686] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Turrini P, Sasso R, Germoni S, Marcucci I, Celluci A, Di Marco A, Marra E, Paonessa G, Eutropi A, Laufer R. Development of humanized mice for the study of hepatitis C virus infection. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:1181-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Walters KA, Joyce MA, Thompson JC, Smith MW, Yeh MM, Proll S, Zhu LF, Gao TJ, Kneteman NM, Tyrrell DL. Host-specific response to HCV infection in the chimeric SCID-beige/Alb-uPA mouse model: role of the innate antiviral immune response. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kneteman NM, Weiner AJ, O'Connell J, Collett M, Gao T, Aukerman L, Kovelsky R, Ni ZJ, Zhu Q, Hashash A. Anti-HCV therapies in chimeric scid-Alb/uPA mice parallel outcomes in human clinical application. Hepatology. 2006;43:1346-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Walters KA, Joyce MA, Thompson JC, Proll S, Wallace J, Smith MW, Furlong J, Tyrrell DL, Katze MG. Application of functional genomics to the chimeric mouse model of HCV infection: optimization of microarray protocols and genomics analysis. Virol J. 2006;3:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Koike K. Hepatitis C as a metabolic disease: Implication for the pathogenesis of NASH. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Asselah T, Rubbia-Brandt L, Marcellin P, Negro F. Steatosis in chronic hepatitis C: why does it really matter? Gut. 2006;55:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Koike K. Hepatitis C virus infection can present with metabolic disease by inducing insulin resistance. Intervirology. 2006;49:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, Tsutsumi T, Tsukamoto K, Kimura S, Moriya K, Koike K. Hepatitis C virus infection and diabetes: direct involvement of the virus in the development of insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:840-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kawaguchi T, Yoshida T, Harada M, Hisamoto T, Nagao Y, Ide T, Taniguchi E, Kumemura H, Hanada S, Maeyama M. Hepatitis C virus down-regulates insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 through up-regulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1499-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ramalho F. Hepatitis C virus infection and liver steatosis. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:125-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Moriya K, Todoroki T, Tsutsumi T, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Miyoshi H, Ishibashi K, Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Watanabe K. Increase in the concentration of carbon 18 monounsaturated fatty acids in the liver with hepatitis C: analysis in transgenic mice and humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:1207-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Perlemuter G, Sabile A, Letteron P, Vona G, Topilco A, Chrétien Y, Koike K, Pessayre D, Chapman J, Barba G. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits microsomal triglyceride transfer protein activity and very low density lipoprotein secretion: a model of viral-related steatosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Perlemuter G, Lettéron P, Carnot F, Zavala F, Pessayre D, Nalpas B, Bréchot C. Alcohol and hepatitis C virus core protein additively increase lipid peroxidation and synergistically trigger hepatic cytokine expression in a transgenic mouse model. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1020-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Moriya K, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Tsutsumi T, Ishibashi K, Matsuura Y, Kimura S, Miyamura T, Koike K. The core protein of hepatitis C virus induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:1065-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in RCA: 912] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Moriya K, Nakagawa K, Santa T, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, Tsutsumi T, Miyazawa T, Ishibashi K, Horie T. Oxidative stress in the absence of inflammation in a mouse model for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4365-4370. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Moriya K, Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Ishibashi K, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T, Koike K. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces hepatic steatosis in transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1527-1531. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Tsutsumi T, Suzuki T, Shimoike T, Suzuki R, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Matsuura Y, Koike K, Miyamura T. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with retinoid X receptor alpha modulates its transcriptional activity. Hepatology. 2002;35:937-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tsutsumi T, Suzuki T, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, Matsuura Y, Koike K, Miyamura T. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates ERK and p38 MAPK in cooperation with ethanol in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2003;38:820-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tsutsumi T, Suzuki T, Moriya K, Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Matsuura Y, Kimura S, Koike K, Miyamura T. Alteration of intrahepatic cytokine expression and AP-1 activation in transgenic mice expressing hepatitis C virus core protein. Virology. 2002;304:415-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yoshida T, Hanada T, Tokuhisa T, Kosai K, Sata M, Kohara M, Yoshimura A. Activation of STAT3 by the hepatitis C virus core protein leads to cellular transformation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:641-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Miyoshi H, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Tsutsumi T, Shinzawa S, Makuuchi M, Kokudo N, Matsuura Y, Suzuki T, Miyamura T. Hepatitis C virus core protein exerts an inhibitory effect on suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 gene expression. J Hepatol. 2005;43:757-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ishikawa T, Shibuya K, Yasui K, Mitamura K, Ueda S. Expression of hepatitis C virus core protein associated with malignant lymphoma in transgenic mice. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;26:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kato T, Miyamoto M, Date T, Yasui K, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Ohue C, Yagi S, Seki E, Hirano T. Repeated hepatocyte injury promotes hepatic tumorigenesis in hepatitis C virus transgenic mice. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Pasquinelli C, Shoenberger JM, Chung J, Chang KM, Guidotti LG, Selby M, Berger K, Lesniewski R, Houghton M, Chisari FV. Hepatitis C virus core and E2 protein expression in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 1997;25:719-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kamegaya Y, Hiasa Y, Zukerberg L, Fowler N, Blackard JT, Lin W, Choe WH, Schmidt EV, Chung RT. Hepatitis C virus acts as a tumor accelerator by blocking apoptosis in a mouse model of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2005;41:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Honda A, Hatano M, Kohara M, Arai Y, Hartatik T, Moriyama T, Imawari M, Koike K, Yokosuka O, Shimotohno K. HCV-core protein accelerates recovery from the insensitivity of liver cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis induced by an injection of anti-Fas antibody in mice. J Hepatol. 2000;33:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Soguero C, Joo M, Chianese-Bullock KA, Nguyen DT, Tung K, Hahn YS. Hepatitis C virus core protein leads to immune suppression and liver damage in a transgenic murine model. J Virol. 2002;76:9345-9354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cruise MW, Lukens JR, Nguyen AP, Lassen MG, Waggoner SN, Hahn YS. Fas ligand is responsible for CXCR3 chemokine induction in CD4+ T cell-dependent liver damage. J Immunol. 2006;176:6235-6244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Cruise MW, Melief HM, Lukens J, Soguero C, Hahn YS. Increased Fas ligand expression of CD4+ T cells by HCV core induces T cell-dependent hepatic inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:412-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Honda A, Arai Y, Hirota N, Sato T, Ikegaki J, Koizumi T, Hatano M, Kohara M, Moriyama T, Imawari M. Hepatitis C virus structural proteins induce liver cell injury in transgenic mice. J Med Virol. 1999;59:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Naas T, Ghorbani M, Alvarez-Maya I, Lapner M, Kothary R, De Repentigny Y, Gomes S, Babiuk L, Giulivi A, Soare C. Characterization of liver histopathology in a transgenic mouse model expressing genotype 1a hepatitis C virus core and envelope proteins 1 and 2. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2185-2196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wakita T, Katsume A, Kato J, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Kanegae Y, Saito I, Hayashi Y, Koike M, Miyamoto M. Possible role of cytotoxic T cells in acute liver injury in hepatitis C virus cDNA transgenic mice mediated by Cre/loxP system. J Med Virol. 2000;62:308-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Wakita T, Taya C, Katsume A, Kato J, Yonekawa H, Kanegae Y, Saito I, Hayashi Y, Koike M, Kohara M. Efficient conditional transgene expression in hepatitis C virus cDNA transgenic mice mediated by the Cre/loxP system. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9001-9006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Alonzi T, Agrati C, Costabile B, Cicchini C, Amicone L, Cavallari C, Rocca CD, Folgori A, Fipaldini C, Poccia F. Steatosis and intrahepatic lymphocyte recruitment in hepatitis C virus transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1509-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Machida K, Cheng KT, Sung VM, Lee KJ, Levine AM, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus infection activates the immunologic (type II) isoform of nitric oxide synthase and thereby enhances DNA damage and mutations of cellular genes. J Virol. 2004;78:8835-8843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Takaku S, Nakagawa Y, Shimizu M, Norose Y, Maruyama I, Wakita T, Takano T, Kohara M, Takahashi H. Induction of hepatic injury by hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ murine cytotoxic T lymphocytes in transgenic mice expressing the viral structural genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:330-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Koike K, Moriya K, Ishibashi K, Matsuura Y, Suzuki T, Saito I, Iino S, Kurokawa K, Miyamura T. Expression of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins in transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:3031-3038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Frelin L, Brenndörfer ED, Ahlén G, Weiland M, Hultgren C, Alheim M, Glaumann H, Rozell B, Milich DR, Bode JG. The hepatitis C virus and immune evasion: non-structural 3/4A transgenic mice are resistant to lethal tumour necrosis factor alpha mediated liver disease. Gut. 2006;55:1475-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Majumder M, Ghosh AK, Steele R, Zhou XY, Phillips NJ, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein impairs TNF-mediated hepatic apoptosis, but not by an anti-FAS antibody, in transgenic mice. Virology. 2002;294:94-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Majumder M, Steele R, Ghosh AK, Zhou XY, Thornburg L, Ray R, Phillips NJ, Ray RB. Expression of hepatitis C virus non-structural 5A protein in the liver of transgenic mice. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:528-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Blindenbacher A, Duong FH, Hunziker L, Stutvoet ST, Wang X, Terracciano L, Moradpour D, Blum HE, Alonzi T, Tripodi M. Expression of hepatitis c virus proteins inhibits interferon alpha signaling in the liver of transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1465-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Duong FH, Filipowicz M, Tripodi M, La Monica N, Heim MH. Hepatitis C virus inhibits interferon signaling through up-regulation of protein phosphatase 2A. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:263-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Duong FH, Christen V, Berke JM, Penna SH, Moradpour D, Heim MH. Upregulation of protein phosphatase 2Ac by hepatitis C virus modulates NS3 helicase activity through inhibition of protein arginine methyltransferase 1. J Virol. 2005;79:15342-15350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sarcar B, Ghosh AK, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A mediated STAT3 activation requires co-operation of Jak1 kinase. Virology. 2004;322:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Feinstone SM, Alter HJ, Dienes HP, Shimizu Y, Popper H, Blackmore D, Sly D, London WT, Purcell RH. Non-A, non-B hepatitis in chimpanzees and marmosets. J Infect Dis. 1981;144:588-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Garson JA, Whitby K, Watkins P, Morgan AJ. Lack of susceptibility of the cottontop tamarin to hepatitis C infection. J Med Virol. 1997;52:286-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Abe K, Kurata T, Teramoto Y, Shiga J, Shikata T. Lack of susceptibility of various primates and woodchucks to hepatitis C virus. J Med Primatol. 1993;22:433-434. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Sithebe NP, Kew MC, Mphahlele MJ, Paterson AC, Lecatsas G, Kramvis A, de Klerk W. Lack of susceptibility of Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus orientalis) to hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol. 2002;66:468-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Xie ZC, Riezu-Boj JI, Lasarte JJ, Guillen J, Su JH, Civeira MP, Prieto J. Transmission of hepatitis C virus infection to tree shrews. Virology. 1998;244:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Simons JN, Pilot-Matias TJ, Leary TP, Dawson GJ, Desai SM, Schlauder GG, Muerhoff AS, Erker JC, Buijk SL, Chalmers ML. Identification of two flavivirus-like genomes in the GB hepatitis agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3401-3405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Lanford RE, Chavez D, Notvall L, Brasky KM. Comparison of tamarins and marmosets as hosts for GBV-B infections and the effect of immunosuppression on duration of viremia. Virology. 2003;311:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Benali-Furet NL, Chami M, Houel L, De Giorgi F, Vernejoul F, Lagorce D, Buscail L, Bartenschlager R, Ichas F, Rizzuto R. Hepatitis C virus core triggers apoptosis in liver cells by inducing ER stress and ER calcium depletion. Oncogene. 2005;24:4921-4933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Wang AG, Moon HB, Lee YH, Yu SL, Kwon HJ, Han YH, Fang W, Lee TH, Jang KL, Kim SK. Transgenic expression of Korean type hepatitis C virus core protein and related mutants in mice. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:588-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Okuda M, Li K, Beard MR, Showalter LA, Scholle F, Lemon SM, Weinman SA. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:366-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 679] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Korenaga M, Wang T, Li Y, Showalter LA, Chan T, Sun J, Weinman SA. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits mitochondrial electron transport and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37481-37488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Kawamura T, Furusaka A, Koziel MJ, Chung RT, Wang TC, Schmidt EV, Liang TJ. Transgenic expression of hepatitis C virus structural proteins in the mouse. Hepatology. 1997;25:1014-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Machida K, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Seike E, Toné S, Shibasaki F, Shimizu M, Takahashi H, Hayashi Y, Funata N, Taya C. Inhibition of cytochrome c release in Fas-mediated signaling pathway in transgenic mice induced to express hepatitis C viral proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12140-12146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Koike K, Moriya K, Ishibashi K, Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Kurokawa K, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T. Sialadenitis histologically resembling Sjogren syndrome in mice transgenic for hepatitis C virus envelope genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:233-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Disson O, Haouzi D, Desagher S, Loesch K, Hahne M, Kremer EJ, Jacquet C, Lemon SM, Hibner U, Lerat H. Impaired clearance of virus-infected hepatocytes in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:859-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Erdtmann L, Franck N, Lerat H, Le Seyec J, Gilot D, Cannie I, Gripon P, Hibner U, Guguen-Guillouzo C. The hepatitis C virus NS2 protein is an inhibitor of CIDE-B-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18256-18264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Furutani T, Hino K, Okuda M, Gondo T, Nishina S, Kitase A, Korenaga M, Xiao SY, Weinman SA, Lemon SM. Hepatic iron overload induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2087-2098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |