Published online Apr 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2374

Revised: January 10, 2006

Accepted: February 8, 2007

Published online: April 28, 2007

AIM: To summarize the experience in diagnosis, management and prevention of iatrogenic bile duct injury (IBDI).

METHODS: A total of 210 patients with bile duct injury occurred during cholecystectomy admitted to Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital from March 1990 to March 2006 were included in this study for retrospective analysis.

RESULTS: There were 59.5% (103/173) of patients with IBDI resulting from the wrong identification of the anatomy of the Calot’s triangle during cholecystectomy. The diagnosis of IBDI was made on the basis of clinical features, diagnostic abdominocentesis and imaging findings. Abdominal B ultrasonography (BUS) was the most popular way for IBDI with a diagnostic rate of 84.6% (126/149). Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) could reveal the site of injury, the length of injured bile duct and variation of bile duct tree with a diagnostic rate 100% (45/45). According to the site of injury, IBDI could be divided into six types. The most common type (type 3) occurred in 76.7% (161/210) of the patients and was treated with partial resection of the common hepatic duct and common bile duct. One hundred and seventy-six patients were followed up. The mean follow-up time was 3.7 (range 0.25-10) years. Good results were achieved in 87.5% (154/176) of the patients.

CONCLUSION: The key to prevention of IBDI is to follow the “identifying-cutting-identifying” principle during cholecystectomy. Re-operation time and surgical procedure are decided according to the type of IBDI.

- Citation: Wu JS, Peng C, Mao XH, Lv P. Bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy: Sixteen-year experience. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(16): 2374-2378

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i16/2374.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2374

Bile duct injury (BDI) occurring during cholecystectomy has been proposed as the most serious and important cause of morbidity after this procedure[1-3]. Although the reported incidence may be less than 0.7%[4,5], the true incidence is unknown. It has been suggested that half of all general surgeons may encounter bile duct injuries[6]. The diagnosis, management and prevention of iatrogenic bile duct injuries (IBDI) remain a challenge for all general surgeons. Between March 1990 and March 2006, 210 patients underwent surgery for IDBI in Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital. No death occurred and a successful long-term outcome was achieved in 87.5% of the patients. The aim of this study was to retrospectively review the clinical data of these patients, analyze the causes of IBDI and introduce our experience in diagnosis, management and prevention of IBDI.

Two hundred and ten patients with IBDI with no cystic duct stump leaks were included in this study. There were 64 males and 146 females at the age of 23-68 years (average 46.5 years). Cholecystolithiasis and gallbladder polyps were the surgical indications. Iatrogenic injury was found in 48 patients at laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and in 162 patients at open cholecytectomy (OC).

The causes of IBDI were identified in 173 patients (82.4%). The most frequent cause was poor identification of the anatomical features of the Calot triangle (59.5%), followed by anatomical anomalism (12.7%), unspecified technical mistake (11.0%), control of intraoperative hemorrhage (8.1%), operation with blind confidence (5.8%), retrograde cholecystectomy for safety (2.9%).

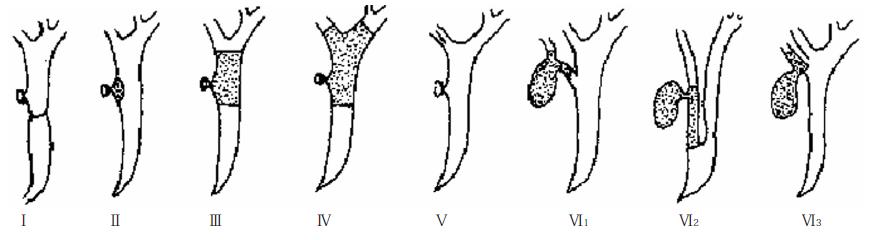

Bile duct injuries were grouped according to the Wu’s classification[7] (Figure 1), the length of BDI, diameter of injured bile duct (IBD) and factors leading to BDI (Table 1).

| Type | n (%) | Length | n (%) | Diameter | n (%) | Factors | n (%) |

| I | 4 (1.9) | < 3 cm | 63 (30.0) | > 3 mm | 189 (90.0) | Ligature | 3 (1.4) |

| II | 3 (1.4) | > 3 cm | 132 (62.9) | < 3 mm | 12 (5.7) | Scissors | 156 (74.3) |

| III | 161 (76.7) | Unidentified | 15 (7.1) | Unidentified | 9 (4.3) | Diathermy | 46 (21.4) |

| IV | 9 (4.3) | Misapplied clips | 1 (0.05) | ||||

| V | 3 (1.4) | Unidentified | 5 (2.4) | ||||

| VI1 | 4 (1.9) | ||||||

| VI2 | 5 (2.4) | ||||||

| VI3 | 10 (4.8) | ||||||

| Unidentified | 11 (5.2) |

TypeIinjuries originate from common bile duct occluded by silk ligature or metallic clips. Type II injuries involve part of the confluence of the cystic duct, common hepatic duct and common bile duct excised. Type III injuries involve part of the common bile duct and common hepatic duct excised. Type IV injuries involve the common bile duct and common hepatic duct including the junction of the right and left hepatic ducts. Type V injuries include laceration or perforation of the right hepatic duct.

The main postoperative complications associated with BDI were secondary hepatobiliary stones in 28 patients (13.3%), liver cirrhosis in 10 patients (4.8%), atrophy of right posterior sector of the liver in 2 patients (0.1%) and liver abscess in 2 patients (0.1%).

Clinical manifestation: A total of 61 BDI patients (29.0%) were diagnosed during cholecystectomy by the presence of bile leaking in the operative field and a double biliary stump. The remaining 149 patients (71.0%) were diagnosed postoperatively. One hundred and six patients (50.5%) were recognized in the early stage (within 3 mo after BDI). The main clinical manifestations were abdominal pain in 83.0%, biliary fistula (bilious drainage from an operatively placed drain or abdominal incision) in 44.3%, peritonitis in 39.6%, abdominal shift dullness in 29.2% and jaundice in 19.8% patients. Besides, bile was found during diagnostic abdominocentesis in 36.8% of patients in early postoperative stage. The other 43 patients (20.5%) were recognized in the late postoperatively stage (over 3 mo after BDI). The main clinical manifestations were recurrent chill, fever, jaundice and abnormal liver function tests.

Imaging: Imaging exzamination included BUS, CT, magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreato-graphy (ERCP), T tube cholangiography, fistula, etc (Table 2). BUS could reveal subhepatic fluid collection, proximal biliary tree dilatation and disruption of continuity of the bile duct. CT scan could display the dilated proximal biliary tree, the level and length of BDI. ERCP could show small distal common bile duct (CBD) or disruption of the CBD and lack of visualization of the proximal biliary tree. PTC showed intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, disruption or stenosis of the bile duct. PTC + ERCP could reveal the level and length of BDI. T tube cholangiography showed disruption or real stenosis of the bile duct. Fistula cholangiography displayed contrast agent entering intrahepatic bile duct, stenosis of common hepatic duct. MRC could reveal proximal bile duct dilatation of BDI, the level and length of BDI and variation of bile duct tree. The BUS was the most popular way for IBDI in this group with a diagnostic rate of 84.6% (126/149). MRC checked had a diagnostic rate of 100% (45/45).

| Imaging | n | Diagnosed injuries (%) |

| BUS | 149 | 126 (84.6) |

| CT | 124 | 103 (83.1) |

| PTC | 20 | 6 (30.0) |

| ERCP | 53 | 36 (67.9) |

| ERCP + PTC | 7 | 3 (42.9) |

| MRC | 45 | 45 (100.0) |

| T tube cholangiography | 28 | 10 (35.7) |

| Fistula cholangiography | 20 | 9 (45.0) |

Before the patients were referred to our hospital, 13 underwent right and/or left hepatic duct drainage + abdominal drainage, 10 received end-to-end anastomosis over the T tube, 122 had Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, 3 had liver lobectomy and 1 had pancreatoduodenectomy. Technical errors in choledochojejunostomy included ductal end not trimmed properly and/or the scar of injured duct not eliminated, anastomosis performed using a large needle and suture, anastomosis stoma torsion and suture, Roux-en-Y loop mesentery tension and Roux-en-Y loop jejuno- jejunum reverse anastomosis, right posterior hepatic duct stayed outside the anastomosis and missed anastomosis of even Roux-en-Y loop, etc.

Technical errors in end-to-end anastomosis cases also included improper trimming of ductal end, scar not removed, anastomosis stoma torsion and suture, etc. Among these cases, bile duct stents were placed in 5 cases for more than 12 mo. Obstructive jaundice was observed 5 to 7 d after the stents were removed.

After the patients were referred to our hospital, iatrogenic bile duct injuries were repaired with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (Table 3). Among these cases, Roux-en-Y jejunal limb drain was not placed in 46 patients.

| Type of repair | Diagnosedduringoperation(n = 61) | Recognizedin earlystage(n = 106) | Recognizedin latestage(n = 43) |

| RHD injury repair + T tube drainage | 3 | ||

| Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | 48 | 103 | 36 |

| End-to-end anastomosis + T tube drainage | 4 | 6 | |

| Releasing ligation + T tube drainage | 3 | ||

| RHD and/or LHD drainage to outside | 6 | ||

| Liver lobectomy + hepaticojejunostomy | 2 |

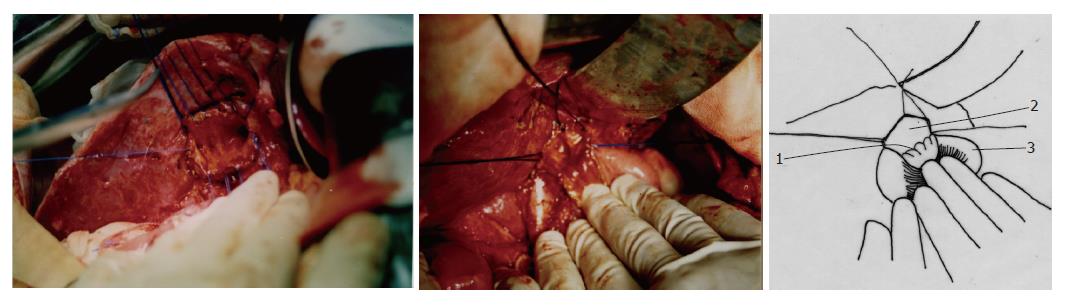

When all the adhesions to the right upper quadrant were sectioned, the jejunal limb was dissected. Hepa-tobiliary basin-jejunostomy with wrist band style ecstrophy anastomosis was performed with interrupted 4/0 or 5/0 absorbable sutures (Figure 2). Liver resection of segment IV base was done when the liver was overhanging the upper ducts, allowing adequate exposure of the left duct. To obtain a complete view of the confluence and/or the isolated right and left hepatic ducts and to allow free placement of the jejunal limb, liver parenchyma could be removed. When the retractors were released, there was no external compression over the jejunum. Partial injuries to the side wall of the bile duct were repaired primarily with T tube placement through a separate choledochotomy when there was no evidence of ductal devascularization and when the margins of the defect could be approximated without tension. Injuries to isolated sectoral or segmental ducts were repaired or drained into a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum. If isolated ducts were found and the distance between them was appropriate (< 1 cm), a hepatobiliary basin could be created by stitching the medial and lateral borders of the right and left ducts. The bilioenteric anastomosis was performed all around the circumference of the hepatobiliary basin.

No perioperative death occurred in this series of patients. Postoperative outcome after reconstruction was evaluated. Longer-term follow-up was achieved through outpatient visit, telephone review and referring surgeon liaison. The long-term outcome was assessed by clinical symptoms and liver function tests. Resolution of obstructive episode and/or cholangitis was defined as good results. One hundred and seventy six patients were followed up. The mean time of follow-up was 3.7 (range 0.25-10) years. Good result rate was 87.5% (154/176). Symptoms suggestive of cholangitis developed in 3 patients within 12 mo, but imaging failed to demonstrate any stricture. Two patients underwent end-to-end anastomosis and T tube stent for 1 year. The late complication was a recurrent biliary structure and received Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy 3 and 5 years after operation.

BDI is still a serious complication of cholecystectomy with a long-term morbidity[8,9], reduced survival[10] and impaired quality of life[11,12]. Although the reported incidence may be less than 0.7%, the true incidence is unknown. Some injuries remain unrecognized for many years, occasionally coming to light only when the patient develops secondary biliary cirrhosis[13]. Cholecystectomy is a kind of operation full of danger[14]. It could be said, to some extent, cholecystectomy is the surgeon’s tomb.

The causes of IBDI in this series were as many as ten kinds. Since the fundamental cause of BDI during cholecystectomy is removal of gallbladder without identifying the anatomy of the Calot’s triangle, identifying common bile duct (CBD) and common hepatic duct (CHD) before transacting cystic duct is the fundamental measure to prevent IBDI. Three-step principle of “identifying-cutting-identifying” should be recommended during cholecystectomy, namely, identifying CBD and CHD before cutting the cystic duct and identifying the integrality of CBD and CHD again after removal of the gall bladder. Immediate recognition and correct repair of BDI have long been believed to be associated with the best long-term results. In this series, BDI occurred in 15 patients and was recognized during cholecystectomy and managed correctly.

Several classifications of BDI have been proposed[15-17], but none is accepted as a universal standard. Neither the Strasberg et al[18] nor the Bismuth[19] classification clearly describes one of the most serious injuries. An ideal classification should not only consider the level of BDI, but also take into account the length and diameter of BDI as well as instruments leading to BDI and vascular injury. Such classifications are useful for standardization of outcome and prediction of prognosis. More important is such classifications can not only differentiate the extent of BDI, but also guide the surgical management of BDI. The management of typeIinjuries is to release the tie or clip with T tube placement and drainage, but type IV injuries most probably need hepaticojejunostomy. The correct management of BDI with the length beyond 3 cm is hepaticojejunostomy. BDI caused by electrocoagulation or electrotome, usually presents as scorched eschar in the operation region, and is difficult to do end-to-end anastomosis. With respect to the Wu’s classification, the most common type was type III injuries (81%), followed by type IV injuries (4.76%) in our series. Attention should be paid to type VI injuries (9%) they are associated with aberrant right hepatic duct.

Recognition of BDI at the time of cholecystectomy allows an opportunity for the surgeon to assess its severity and the presence of any vascular injury. If bile or a double biliary stump presents in the operative field during cholecystectomy, BDI should be considered. A total of 61 BDIs were diagnosed during cholecystectomy in our series, among which 61 (100%) with bile leaking and 58 (95%) with double biliary stump were found in the operative field. As many as 149 cases (71.0%) of BDI were not diagnosed during surgery in this series. BDI should be considered when the following manifestations occurred after cholecystectomy: presence of jaundice in the early postoperative period, presence of peritonitis or bile from abdominal centesis, patients with gradual distention of their abdomen, imaging examination revealing intrahepatic duct dilatation and unclear unclear extrahepatic duct.

The sign of peritonitis may not be obvious, because biliary peritonitis is not typical in some patients taking broad-spectrum antibiotics, whose clinical presentation can be only abdominal distention. There were 18 cases (12.1%) in our study and abdominal centesis was of diagnostic value in these cases.

Late presentations include recurrent cholangitis and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Investigations usually include abdominal ultrasonography and liver function test. B ultrasonography is the most popular examination. All postoperative patients in our series accepted this examination, revealing interrupted ductal continuity, fluid collections and mandate aspiration or drainage. CT scan displayed dilated proximal biliary tree, level and length of BDI. If ultrasonography and CT scan results are equivocal in a symptomatic patient, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography could be performed as its sensitivity is higher than ultrasonography and CT scan (100.0% vs 83.1%-84.6%). Following drainage of any collection, contrast studies through the drains may be useful in further elucidating the nature of any injury or leak.

The repair time of BDI after remains controversial[20-22]. To determine the time of re-operation, the following items should be noticed according to our experience. (1) The proximal bile duct should be dilatated with its diameter exceeding 8mm. (2) Chill, fever and jaundice are not contraindications of operation. (3) Abscess presenting around the injured bile duct is a contraindication of operation.

Operative technique focuses on the site of proximal IBD and takes corresponding operation procedure according to the type of BDI. Patients with BDI are not suitable for Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy when the diameter of proximal bile duct is less than 3 mm and end-to-end anastomosis when the diameter of proximal bile duct is longer than 3 cm. A transection or stricture of the bile duct is repaired by hepaticojejunostomy (189 cases in this series) to the biliary confluence with extension into the left and/or right hepatic duct, with interrupted 4/0 or 5/0 absobebable sutures onto a 35 cm Roux-en-Y limb of proximal jejunum. When hepaticojejunostomy is performed, the following manoeuvres may be helpful according to our experience. (1) The hepatic hilus great triangle should be ascertained to downsize the area for seeking the injured bile duct. (2) Cordlike tissue or tissue with a sense of cyst near hepatic hilus usually clues on the site of bile duct. (3) Ligamentum teres approach can identify the left duct, and gallbladder bed approach can identify the right duct[23]. Resecting liver parenchyma of segments IV and V helps to expose hepatic hilus bile duct. (4) To achieve a wide hepatobiliary basin (1-3 cm), we could section the anterior surface of the common duct, directing it to the anterior surface of the left or/and right duct. (5) Tension-free anastomosis can achieved by obtaining an adequate free limb by preparing the mesenterium, with preservation of the vascular arcades. The jejunal limb should be in-phase with duodenum but not with climb across duodenum. (6) Factors associated with an improved outcome include the use of micro-invasive absorbable sutures, single-layer anastomoses, nonischemic mucosa-mucosa anastomosis and debridement.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Che YB

| 1. | Thomson BN, Parks RW, Madhavan KK, Wigmore SJ, Garden OJ. Early specialist repair of biliary injury. Br J Surg. 2006;93:216-220. |

| 2. | Diamantis T, Tsigris C, Kiriakopoulos A, Papalambros E, Bramis J, Michail P, Felekouras E, Griniatsos J, Rosenberg T, Kalahanis N. Bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy: an 11-year experience in one institute. Surg Today. 2005;35:841-845. |

| 3. | Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003;289:1639-1644. |

| 4. | Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1356-1360. |

| 5. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Tielve M, Hinojosa CA. Acute bile duct injury. The need for a high repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1351-1355. |

| 6. | Francoeur JR, Wiseman K, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Scudamore CH. Surgeons' anonymous response after bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2003;185:468-475. |

| 7. | Wu JS, Mao XH, Liao CH. Treatment of iatrogenic bile duct trauma. Zhongguo Putong Waike Zazhi. 2001;10:42-45. |

| 8. | Mirza DF, Narsimhan KL, Ferraz Neto BH, Mayer AD, McMaster P, Buckels JA. Bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: referral pattern and management. Br J Surg. 1997;84:786-790. |

| 9. | Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, Tsuneyama K, Matsui K, Haratake J, Sakisaka S, Maeyama S, Yamamoto K, Nakano M. Are bile duct lesions of primary biliary cirrhosis distinguishable from those of autoimmune hepatitis and chronic viral hepatitis? Interobserver histological agreement on trimmed bile ducts. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:164-170. |

| 10. | Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168-2173. |

| 11. | Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, Wudel LJ, Strickland C, Gorden DL, Chari R, Wright JK, Pinson CW. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg. 2004;139:476-481; discussion 481-482. |

| 12. | Melton GB, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Sauter PA, Coleman J, Yeo CJ. Major bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: effect of surgical repair on quality of life. Ann Surg. 2002;235:888-895. |

| 13. | Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, Neuhaus P. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:76-82. |

| 14. | Yang JM. Cholecystectomy and bile duct injury. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 1999;19:454-456. |

| 15. | Stewart L, Robinson TN, Lee CM, Liu K, Whang K, Way LW. Right hepatic artery injury associated with laparoscopic bile duct injury: incidence, mechanism, and consequences. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:523-530. |

| 16. | Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2004;135:613-618. |

| 17. | Csendes A, Navarrete C, Burdiles P, Yarmuch J. Treatment of common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: endoscopic and surgical management. World J Surg. 2001;25:1346-1351. |

| 18. | Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101-125. |

| 19. | Bismuth H. Postoperative strictures of the bile duct. Blumgart LH (editor). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 1982; 209-218. |

| 20. | Chaudhary A, Chandra A, Negi SS, Sachdev A. Reoperative surgery for postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries. Dig Surg. 2002;19:22-27. |

| 21. | Connor S, Garden OJ. Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:158-168. |

| 22. | Moraca RJ, Lee FT, Ryan JA, Traverso LW. Long-term biliary function after reconstruction of major bile duct injuries with hepaticoduodenostomy or hepaticojejunostomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:889-893; discussion 893-894. |

| 23. | Wu JS. Clinical cholelithiology. Changsha: Hunan Science & Technology Press 1998; 436-439. |