Published online Apr 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i15.2238

Revised: January 12, 2007

Accepted: March 14, 2007

Published online: April 21, 2007

To describe a case of probable relapsing autoimmune hepatitis associated with vaccination against hepatitis A virus (HAV). A case report and review of literature were written concerning autoimmune hepatitis in association with hepatitis A and other hepatotropic viruses. Soon after the administration of formalin-inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, a man who had recently recovered from an uncharacterized but self-limiting hepatitic illness, experienced a severe deterioration (AST 1687 U/L, INR 1.4). Anti-nuclear antibodies were detectable, and liver biopsy was compatible with autoimmune hepatitis. The observation supports the role of HAV as a trigger of autoimmune hepatitis. Studies in helper T-cell activity and antibody expression against hepatic proteins in the context of hepatitis A infection are summarized, and the concept of molecular mimicry with regard to other forms of viral hepatitis and autoimmunity is briefly explored.

- Citation: Berry P, Smith-Laing G. Hepatitis A vaccine associated with autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(15): 2238-2239

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i15/2238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i15.2238

There is substantial evidence favoring hepatitis A virus (HAV) as an etiological factor in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). This includes individual case reports of persistent hepatic inflammation, with serological and histological features of AIH following proven infection with HAV[1,2], and the development of autoantibodies to hepatic constituents during and after HAV infection[3,4]. There have been no reports of AIH in association with vaccination against HAV. Herein we describe the development of severe hepatitis, with serological and biopsy features of AIH, ten days after vaccination against HAV, and five months after the resolution of a self-limiting but uncharacterized hepatitic illness.

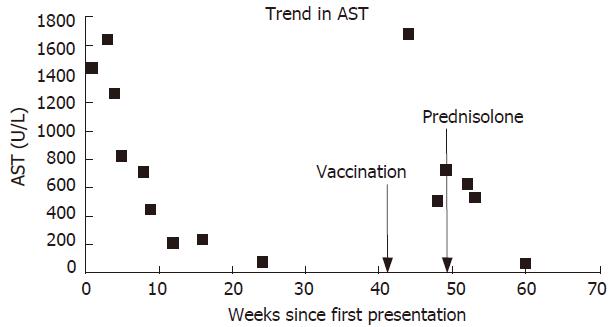

A 56-year-old man presented with jaundice and malaise shortly after a holiday in Greece. There was no history of drug ingestion. Examination was normal apart from the jaundice and mild leg oedema. Blood tests were compatible with acute hepatitis (bilirubin 451 μmol/L, aspartate aminotransferase, 1138 IU/L) and significant impairment of synthetic function (albumin 28 g/L, international normalized ratio [INR] 1.6). Antibodies to hepatitis A, B and C viruses were absent, as were markers suggestive of an autoimmune process, including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), type 1 anti-liver/kidney microsomal antibody (ALKM1) and anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA). Tests for iron and copper storage disorders were negative. Ultrasound scan of the liver was normal. Hepatic function improved without specific treatment, and four months later liver function tests became completely normal (Figure 1).

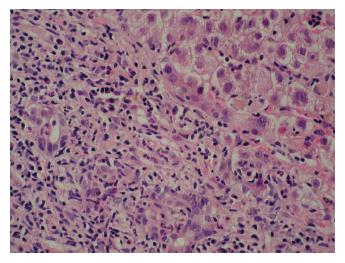

Five months later he attended clinic urgently complaining of severe lethargy and a return of the jaundice. This occurred ten days after vaccination against HAV, administered prior to a planned holiday. He had taken no new medications, and had drunk alcohol in moderate volume only. Because of his illness he did not go abroad. AST was now 1687 IU/L, and INR was 1.4. A further viral and autoimmune screen proved negative, and a liver biopsy was performed. This showed features of severe hepatitis, with bridging and multiacinar necrosis, and portal tract expansion due to dense lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates (Figure 2).

Three months later AST was still 532 U/L. ANA was detected at a titre of 1:100 with a speckled pattern. Antibody to double stranded DNA was detected at a concentration of 57 IU/L. Serum globulins were now increased to 47 g/L. Viral serology remained negative. Prednisolone 30 mg daily was prescribed, and liver function was improved rapidly. Two months later the patient's symptoms abated and his LFTs nearly normalized once again. He returned to work and remained asymptomatic.

At first presentation this patient had severe but self-limiting seronegative hepatitis. He failed to fulfill standard criteria for the diagnosis of AIH[5], although retrospectively this would appear as the likely diagnosis. A dramatic relapse occurred following vaccination against HAV. During this second phase he did meet diagnostic criteria for ‘probable’ AIH (aggregate score 10 before treatment), and required immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids. This treatment brought about a rapid improvement in liver function tests.

Hepatitis A vaccine contains whole viral particles that are inactivated with formalin, and its involvement in such an illness requires discussion about the role of viral antigens in the etiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Associations between a number of hepatotropic viruses (e.g. measles, Epstein Barr, herpes simplex and hepatitis A, B and C) and autoimmune processes directed against the liver have been described[6], but evidence to suggest an etiological role has been lacking. The strongest evidence is probably related to HAV.

AIH has developed after clinical HAV infection[1,2]. In relatives of patients with AIH, Vento et al[3] demonstrated an intrinsic defect in suppressor-inducer T-cells mediating immune reactivity to a liver antigen (asialoglycoprotein receptor-ASPGR), and described the development of AIH following sub-clinical exposure (seroconversion to HAV) with a simultaneous rise in anti-ASGPR antibodies. The same author found autoantibodies to the liver-derived lipoprotein complex in 10 patients with acute hepatitis A. Antibodies to ASPGR (a constituent of the lipoprotien complex) were detected in 6 of the 10 patients. Similar findings were seen in patients with acute hepatitis B[4]. In this study antibody production did not correlate with the transient cellular immune response, leading the investigators to conclude that antibody production against liver cell surface antigens could be due to viral induction of T-cell independent B lymphocytes.

More recently, attention has focused on the theory of molecular mimicry between the infectious particle and the liver constituent against which the resulting antibodies react. Such mimicry between a viral and a hepatic epitope has been demonstrated. In the case of herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), cytochrome P450 IID6, the target of the major liver-kidney microsomal antibody shares an identical sequence of amino acids with the ‘immediate early protein’ IE 175 of HSV-1[7]. This study also demonstrated a cross reactivity between the same cytochrome and hepatitis C virus infection which is associated with a high incidence of autoantibody development. More recent work has shown molecular mimicry between cytochrome P2D6 and the NS3 and NS5a proteins of HCV[8]. Cytochrome P2D6 is the target of anti-LKM1 antibodies, the classic diagnostic marker of type 2 autoimmune hepatitis. Despite the promising findings to support this theory in other hepatotropic viruses, it should be noted that evidence is still deficient for molecular mimicry in relation to HAV.

Vaccination with inactivated HAV has been available since 1992, and its safety is well documented. The manufacturers have stated that recrudescence of hepatitis is not a known side effect of immunization (private communication), other autoimmune phenomena have not been described[9], and no adverse reactions have been reported in those with pre-existing liver disease. Indeed, vaccination is recommended in such patients if exposure is thought to be likely, and according to Vento et al[3], those made susceptible to AIH by the above-mentioned T-cell deficit.

The recrudescence of this case following vaccination with inactivated HAV adds to the evidence that HAV may trigger autoimmunity against the liver. It should not be interpreted as a side effect based on the vaccine’s track record of safety, but reveals potential connections between two apparently disparate liver pathologies.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Che YB

| 1. | Huppertz HI, Treichel U, Gassel AM, Jeschke R, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Autoimmune hepatitis following hepatitis A virus infection. J Hepatol. 1995;23:204-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singh G, Palaniappan S, Rotimi O, Hamlin PJ. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by hepatitis A. Gut. 2007;56:304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vento S, Garofano T, Di Perri G, Dolci L, Concia E, Bassetti D. Identification of hepatitis A virus as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in susceptible individuals. Lancet. 1991;337:1183-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vento S, McFarlane BM, McSorley CG, Ranieri S, Giuliani-Piccari G, Dal Monte PR, Verucchi G, Williams R, Chiodo F, McFarlane IG. Liver autoreactivity in acute virus A, B and non-A, non-B hepatitis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1988;25:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology. 1993;18:998-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manns MP. Autoimmune hepatitis. Oxford Textbook of Clinical Hepatology. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1999; 1109-1119. |

| 7. | Manns MP, Griffin KJ, Sullivan KF, Johnson EF. LKM-1 autoantibodies recognize a short linear sequence in P450IID6, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1370-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marceau G, Lapierre P, Béland K, Soudeyns H, Alvarez F. LKM1 autoantibodies in chronic hepatitis C infection: a case of molecular mimicry. Hepatology. 2005;42:675-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schattner A. Consequence or coincidence The occurrence, pathogenesis and significance of autoimmune manifestations after viral vaccines. Vaccine. 2005;23:3876-3886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |