Published online Mar 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i11.1696

Revised: January 28, 2006

Accepted: March 12, 2007

Published online: March 21, 2007

AIM: To evaluate computed tomography (CT) findings, useful to suggest the presence of refractory celiac disease (RCD) and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (EATL).

METHODS: Coeliac disease (CD) patients were divided into two groups. GroupI: uncomplicated CD (n = 14) and RCD typeI(n = 10). Group II: RCD type II (n = 15) and EATL (n = 7).

RESULTS: Both groups showed classic signs of CD on CT. Intussusception was seen in 1 patient in groupIvs 5 in group II (P = 0.06). Lymphadenopathy was seen in 5 patients in group II vs no patients in groupI(P = 0.01). Increased number of small mesenteric vessels was noted in 20 patients in groupIvs 11 in group II (P = 0.02). Eleven patients (50%) in group II had a splenic volume < 122 cm3vs 4 in groupI(14%), 10 patients in groupI had a splenic volume > 196 cm3 (66.7%) vs 5 in group II (33.3%) P = 0.028.

CONCLUSION: CT scan is a useful tool in discriminating between CD and (Pre) EATL. RCD II and EATL showed more bowel wall thickening, lymphadenopathy and intussusception, less increase in number of small mesenteric vessels and a smaller splenic volume compared with CD and RCDI.

- Citation: Mallant M, Hadithi M, Al-Toma AB, Kater M, Jacobs M, Manoliu R, Mulder C, van Waesberghe JH. Abdominal computed tomography in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(11): 1696-1700

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i11/1696.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i11.1696

Coeliac disease (CD) is one of the most common immu-nologically mediated gastrointestinal diseases. The preva-lence varies between approximately 1:100 and 1:300 worldwide. Refractory coeliac disease (RCD) is considered when patients show persistent or relapsing symptoms and villous atrophy despite adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD), especially those over the age of 50 years[1]. Two forms of RCD can be discriminated. RCDIwhich is defined as RCD with normal intra-epithelial T lymphocytes (IEL’s) in intestinal biopsies and RCD II defined as RCD with aberrant IEL’s[2,3]. In RCD enteropathy associated T-cell Lymphoma (EATL) can evolve with a 20 time higher relative risk compared to the general population[4-6]. Therefore it is necessary to be able to discriminate uncom-plicated CD from its malignant complications.

Computed tomography (CT) is one of the first radio-logical examinations performed for different indications in patients with CD, especially those with RCD to exclude malignancy. A variety of findings like jenunoileal fold pattern reversal[7], small bowel intussusception[8] and (benign) mesenteric lymphadenopathy[9] have been recognized on CT images in patients with CD. However, no discriminating or specific CT signs have been recognized and described regarding RCD II or EATL. Therefore, we evaluated both the spectrum of abdominal CT findings, useful for suggesting CD and those findings which might be useful to suggest the presence of EATL in adult coeliac patients.

Between January 2003 and January 2005 a total of 46 patients (18 M, 28 F; mean age 58 years, range 18-88 years) with proven CD according to UEGW criteria (2001), were enrolled. All patients were previously diagnosed as having CD, RCDI, RCD II or EATL by clinical evaluation, serology and intestinal biopsy[10]. Patients were divided into two groups: GroupIconsisted of 24 patients with uncomplicated CD (n = 14) and RCD typeI(n = 10), group II consisted of 22 patients with RCD type II (n = 15) and EATL (n = 7). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients who participated in this study. All procedures followed in this study were in accordance with the standards of the institutional ethical committee.

The indications for CT scan were assessment of unexplained recurrent abdominal complaints and/or suspicion of EATL. After overnight fasting, examinations were performed either on a 4-detector (Somatom 'Volume Zoom', Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) or on a 64-detector ('Sensation 64', Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) CT scanner, using either a 2.5 mm or a 0.6 mm collimation, reconstructed in 5 mm contiguous axial slices. Forty-three out of 46 patients received an orally administered diluted solution of barium sulphate suspension (46 mg/g, 49 mg/mL, 900 mL E-Z-CAT, E-Z-EM Canada Inc, Montreal Canada) divided into two doses (450 mL), the night before and the morning of the investigation. Forthy-five minutes prior to imaging, patients received an extra 300-500 mL oral contrast. Because of severe abdominal symptoms or refusal of contrast, 3 patients did not receive oral contrast. Intravenous non-ionic contrast [Ultravist, Iopromide (300 mI/L), Schering, Berlin, Germany] was administered in 42 patients (2 patients refused intravenous contrast and 2 patients supposed to be allergic to contrast) at an injection rate of 3 mL/s (maximum total amount of 100 mL, depending on body weight) with CT acquisition after 70 s.

The following CT findings were evaluated: (1) abnormalities of intestinal fold pattern, (2) bowel dilatation, (3) air excess, (4) fluid excess, (5) bowel wall thickening, (6) intestinal intussusception, (7) ascites, (8) lymphadenopathy, (9) increased number of lymph nodes, (10) mesenteric vascular changes, and (11) splenic size. All CT scans were analyzed by two dedicated radiologists in consensus (MM and JHvW).

Abnormalities of the intestinal fold pattern were defined quantitatively as a decreased number of jejunal folds and/or an increased number ( 'jejunization' ) of ileal folds, measured as the mean number of folds per 2.5 cm in three segments at different locations[7]. Less than 4 jejunal folds per 2.5 cm were considered to be decreased and more than 4 ileal folds per 2.5 cm were considered to be increased[7]. The presence of an equal number of intestinal folds in ileum and jejunum (ileum/jejunum fold ratio ≥ 1) was defined as 'jejunoileal fold pattern reversal' (JFPR)[11-13]. In cases of doubt, abdominal loops in the left upper quadrant were considered to be jejunal and loops in the right lower quadrant were considered to be ileal. Intestinal loops were considered dilated if more than three segments measured equal or more than 3 cm in diameter on transverse images[14].

Fluid excess and air excess were scored directly in patients with dilated intestinal loops on a Likert scale (none/mild/moderate/severe). Fluid excess was indirectly assessed by dilution of oral contrast (flocculation). Air excess was scored as present in case more than 3 segments were dilated with air.

The bowel wall was considered thickened when it measured more than 3 mm in the transverse plane of a fully distended loop[15]. Intussusception was denoted as a target mass or as a more complex layered mass within the bowel lumen[16].

Lymph node enlargement was considered present if nodes measured greater than 1 cm in diameter in their shortest axis. The number of lymph nodes within the mesenterium were scored on a Likert scale (none/mild/moderate/severe). Cavitation of nodes was present by showing a low-density center within the lymph node.

Ascites was evaluated by visual inspection. Increase in splanchnic circulation was scored as the transverse diameter 2-3 cm caudal of the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. Also an increase of number of small vessels within the mesenterium was noted on a Likert scale (none/mild/moderate/severe).

Splenic volume was calculated by the following formula; (30+0.58*(length × width × height). The longest axis in the transversal plane is considered as length, the perpendicular distance is considered the width and the longest cranio-caudal distance is considered as the height of the spleen[17].

Student’s paired t-test, Mann-Whitney, or Fisher’s exact test were used for data analysis when indicated. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Software Package version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Because of lack of intraluminal contrast or lack of dis-tension of the small bowel loops, jejunal fold pattern could only be analyzed in 26 patients whereas ileal fold pattern could be assessed in 29 patients. Ten out of 26 (38%) patients showed a decreased number of jejunal folds, 16 (62%) showed an increased number of folds. Ileal folds were found increased in 5 out of 29 (17%) patients and decreased in 24 (83%) patients. No significant difference was found in JFPR between who both groups. Small bowel dilatation ranged from 30-35 mm and was found in 11/46 patients in total (P = NS). All CT findings are summarized in Table 1.

| CT findings | CD and RCDI | RCDII and EATL | Total |

| Number of patients | 24 | 22 | 46 |

| Gender (F/M) | 18/ 6 | 10/12 | 28/18 |

| Mean age (yr) | 56 | 61 | 58 |

| Jejunal/ileal fold ratio (No of folds/2.5 cm) | 4.5/3.0 | 3.7/2.9 | 4.1/3.0 |

| JFPR | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Bowel dilatation | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Air excess | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Fluid excess | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Increased wall thickness | 10 | 14 | 24 |

| Intussusception | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Ascites | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Increased No of lymph nodes | 16 | 12 | 28 |

| Lymph node cavitation | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Increased splanchnic circulation | 20 | 11 | 31 |

Excess of air was not visible in 24/46 patients, mild in 13 patients, moderate in 7 patients and severe in 2 patients in total. Fluid excess and flocculation were scored as none in 20 (43%) patients, mild in 8 (17%) patients, moderate in 12 (26%) patients and severe in 6 (13%) patients. All findings were equally distributed between the groups.

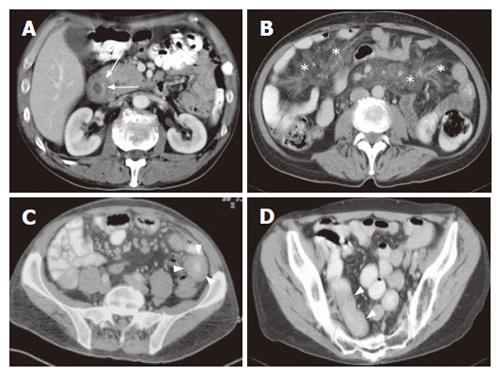

Increased wall thickness ranged from 4 to 11 mm in groupI(mean 7.7 mm, median 7 mm) and from 5 to 15 mm (mean: 9.6 mm, median 10 mm) in group II. Nine patients in group II showed a thickness of more than one cm versus only 4 in groupI(P = NS). Intussusception was observed in only 1 patient in groupI, compared to 5 patients in group II (P = 0.06). Only one patient (RCD II, 67 years old male) showed a small amount of intra-abdominal fluid in the rectovesical pouch.

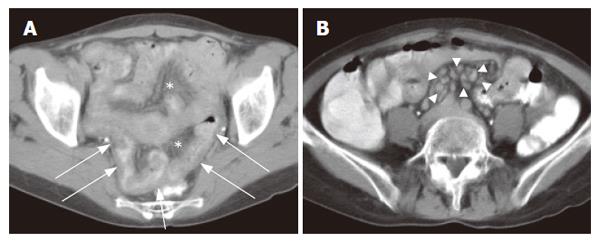

Enlarged lymph nodes were only found in 5 patients in group II (P = 0.013) Both groups showed an increase in non-enlarged lymph nodes (P = 0.295) Only one lymph node showed cavitation (59 year old male with RCD II).

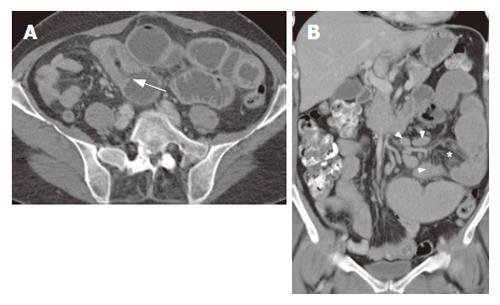

An increase in the number of small mesenterial vessels was observed in 20/24 (83%) patients in groupIvs 11/22 (50%) patients in group II (P = 0.02) The diameter of the superior mesenteric artery was measured in a total of 23 patients and this varied from 4-7 mm.

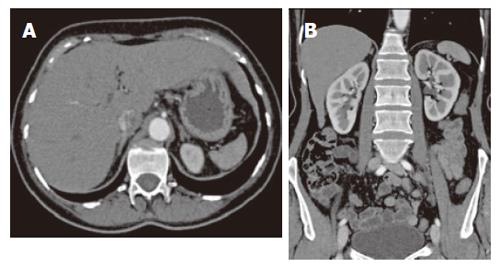

Splenic volume of all patients ranged from 37-321 cm3 (mean 162 cm3) in normal distribution. No significant differences were found between mean volumes in both groupsIand II (178 cm3vs 144 cm3). However, after allocating the patients into 3 arbitrary groups according to the splenic volume, as shown in Table 2, the RCD II and EATL group showed significant more patients with a smaller spleen than RCDI and uncomplicated CD (P = 0.028).

| Splenic volume | CD and RCDI | RCDII and EATL | Total patients |

| Group A: 37-122 cm3 | 4 (27) | 11 (73) | 15 |

| Group B: 124-196 cm3 | 10 (63) | 6 (38) | 16 |

| Group C: 196-321 cm3 | 10 (67) | 5 (33) | 15 |

| Mean volume (cm3) | 178 | 144 | 162 |

In patients clinically suspected of having CD, biopsies are mandatory to confirm or exclude the diagnosis[18]. In uncomplicated cases, radiological examination is not required. However, in clinical practice pre-malignant and malignant complications of CD have to be excluded in patients who have persistent complaints despite strict adherence to a GFD. Furthermore CT, performed in patients presenting with atypical abdominal symptoms, can suggest a diagnosis of CD[13]. The most striking features found in CD are jejunoileal fold pattern reversal, small bowel intussusception, and benign mesenteric lymphadenopathy[7-9,12,13]. However, to our knowledge, no discriminating findings between CD/RCDIand (Pre) EATL have been decribed using CT.

Regarding jejunal and ileal fold abnormalities; especially jejunoileal fold pattern reversal and total loss of jejunal folds may be considered specific findings in CD[7,12,13]. In our study, only in 52% (24 out 46 patients) both jejunal and ileal folds could be assessed because of lack of contrast or lack in distention of small intestinal loops, probably due to suboptimal bowel preparation because of progressive abdominal complaints. In only 9 out 24 (38%) patients a jejunoileal fold pattern reversal was observed. This is a low percentage compared to that reported by Tomei et al[7], however we included a high percentage of patients with RCDI, RCD II and EATL. Furthermore, both increased ileal folds, decreased jejunal folds, and jejunoileal fold pattern reversal were equally distributed between the subgroups, which demonstrates that the number of folds is not a good discriminator between both groups.

Transient intussusception of the small bowel was present in 5 patients in group II compared to one patient in groupI(P = 0.06). The majority of patients showed an increase in the number of nodes (< 1 cm), which was not significantly unequally distributed between both groups CD. However, mesenteric lymphadenopathy (short axis > 1 cm) was only found in the (Pre) EATL group, whereas cavitation, which is considered to be a rare complication associated with a poor outcome[22-24], was found in one patient with RCD II (Figure 1). In this patient additional examinations, including 18F-FDG-PET scan and lapa-rascopic mesenteric lymph nodes resection, did not show any evidence of EATL.

Regarding non-specific signs, bowel dilatation and excess of fluid (with flocculation of contrast) and air[13,19], bowel dilatation and increased splanchnic circulation, as measured using the diameter of the superior mesenteric artery 2-3 cm distal to its origo, we found no significant differences between the two subgroups. However mesen-teric vascularity, as measured using a semi-quantative scale, was significantly increased in groupI. We hypothesize that this increase of small vessels and small lymph nodes in groupImay be due to the acute inflammatory process in this group (Figure 2). Also no significant difference in number of patients with increased wall thickness was found. However more patients in group II showed a wall thickness of more than 1 cm (P = NS, Figures 1, 3 and 4).

Splenic atrophy occurs frequently in patients with CD and is related to the severity of the disease and degree of dietary control and shows a significant correlation with an impaired function with the incidence rising with increasing age of starting treatment[26]. Although no correlation was observed in literature between splenic size and the duration of the GFD as well as the percentage of splenic size recovery after gluten withdrawal, hyposplenism in adult CD was improved by a GFD[27]. Furthermore regarding group II, hyposplenism was not related to the development of malignant disease in small samples[28]. In this study however, significantly more patients in the RCD II/EATL group showed a smaller splenic size (Figures 4 and 5).

In conclusion, both groups showed classic signs of CD on CT. Though small groups were analysed, group II showed more bowel wall thickening, lymphadenopathy, intussusception and more hyposplenism and less increase in splanchnic circulation than groupI. Therefore, we conclude that bowel wall thickening, lymphadenopathy, intussusception and hyposplenism should raise suspicion for RCD II and the development of EATL.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Rampone B E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Mulder CJ, Wahab PJ, Moshaver B, Meijer JW. Refractory coeliac disease: a window between coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2000;32-37. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Goerres MS, Meijer JW, Wahab PJ, Kerckhaert JA, Groenen PJ, Van Krieken JH, Mulder CJ. Azathioprine and prednisone combination therapy in refractory coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daum S, Cellier C, Mulder CJ. Refractory coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:413-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Catassi C, Rätsch IM, Fabiani E, Rossini M, Bordicchia F, Candela F, Coppa GV, Giorgi PL. Coeliac disease in the year 2000: exploring the iceberg. Lancet. 1994;343:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martucci S, Biagi F, Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR. Coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34 Suppl 2:S150-S153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grodzinsky E. Screening for coeliac disease in apparently healthy blood donors. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1996;412:36-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tomei E, Marini M, Messineo D, Di Giovambattista F, Greco M, Passariello R, Picarelli A. Computed tomography of the small bowel in adult celiac disease: the jejunoileal fold pattern reversal. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Strobl PW, Warshauer DM. CT diagnosis of celiac disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:319-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Boer WA, Maas M, Tytgat GN. Disappearance of mesenteric lymphadenopathy with gluten-free diet in celiac sprue. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:317-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | When is a coeliac a coeliac?. Report of a working group of the United European Gastroenterology Week in Amsterdam, 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1123-1128. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Bova JG, Friedman AC, Weser E, Hopens TA, Wytock DH. Adaptation of the ileum in nontropical sprue: reversal of the jejunoileal fold pattern. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:299-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Herlinger H, Maglinte DD. Jejunal fold separation in adult celiac disease: relevance of enteroclysis. Radiology. 1986;158:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tomei E, Diacinti D, Marini M, Mastropasqua M, Di Tola M, Sabbatella L, Picarelli A. Abdominal CT findings may suggest coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:402-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Frager D. Intestinal obstruction role of CT. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:777-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Balthazar EJ. CT of the gastrointestinal tract: principles and interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Merine D, Fishman EK, Jones B, Siegelman SS. Enteroenteric intussusception: CT findings in nine patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:1129-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Prassopoulos P, Daskalogiannaki M, Raissaki M, Hatjidakis A, Gourtsoyiannis N. Determination of normal splenic volume on computed tomography in relation to age, gender and body habitus. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:246-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bai J, Zeballos E, Fried M, Corazza GR, Schuppan D, Farthing MJG, Catassi C, Greco L, Cohen H, Krabshuis JH. WGO-OMGE Practice Guideline Coeliac Disease. World Gastroenterol News. 2005;2:S1-S8. |

| 19. | Rubesin SE, Herlinger H, Saul SH, Grumbach K, Laufer I, Levine MS. Adult celiac disease and its complications. Radiographics. 1989;9:1045-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rettenbacher T, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Huber S, Gritzmann N. Adult celiac disease: US signs. Radiology. 1999;211:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moser PP, Smith JK. CT findings of increased splanchnic circulation in a case of celiac sprue. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:15-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Howat AJ, McPhie JL, Smith DA, Aqel NM, Taylor AK, Cairns SA, Thomas WE, Underwood JC. Cavitation of mesenteric lymph nodes: a rare complication of coeliac disease, associated with a poor outcome. Histopathology. 1995;27:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schmitz F, Herzig KH, Stüber E, Tiemann M, Reinecke-Lüthge A, Nitsche R, Fölsch UR. On the pathogenesis and clinical course of mesenteric lymph node cavitation and hyposplenism in coeliac disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:192-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Freeman HJ, Chiu BK. Small bowel malignant lymphoma complicating celiac sprue and the mesenteric lymph node cavitation syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:2008-2012. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Warshauer DM, Lee JK. Adult intussusception detected at CT or MR imaging: clinical-imaging correlation. Radiology. 1999;212:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wright DH. The major complications of coeliac disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;9:351-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Robinson PJ, Bullen AW, Hall R, Brown RC, Baxter P, Losowsky MS. Splenic size and function in adult coeliac disease. Br J Radiol. 1980;53:532-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | O'Grady JG, Stevens FM, McCarthy CF. Celiac disease: does hyposplenism predispose to the development of malignant disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:27-29. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Corazza GR, Frisoni M, Vaira D, Gasbarrini G. Effect of gluten-free diet on splenic hypofunction of adult coeliac disease. Gut. 1983;24:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |