Published online Mar 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1481

Revised: August 1, 2005

Accepted: October 26, 2005

Published online: March 7, 2006

A 60-years old male was admitted to our department for investigation of constipation and hypogastric discomfort intensified during defecation of a few weeks duration. The cause proved to be a rectal carcinosarcoma that was treated by abdominoperineal resection and postoperative chemo-radiotherapy. The patient died 6 months later due to hepatic failure, showing evidence of disseminated disease. In general colonic carcinosarcomas constitute a rare category of malignant neoplasms whose nature is still incompletely understood. No specific treatment guidelines exist. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment and regardless of the addition of adjuvant therapy the prognosis is very poor. Systematic genetic analysis may be the clue for understanding the pathogenesis of these mysterious tumors.

- Citation: Tsekouras DK, Katsaragakis S, Theodorou D, Kafiri G, Archontovasilis F, Giannopoulos P, Drimousis P, Bramis J. Rectal carcinosarcoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(9): 1481-1484

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i9/1481.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1481

The coexistence of carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements within the same tumor is a rare entity, variably labeled as “carcinosarcoma”, “metaplastic carcinosarcoma”, “sarcomatoid carcinoma”, “pseudosarcomatous carcinoma”, “carcinoma with mesenchymal stroma”, “carcinoma with sarcomatoid change”, “spindle cell carcinoma”, “pleomorphic anaplastic carcinoma” and “small cell carcinoma”[1]. This confusing, non-standardized terminology reflects the rarity and uncertainty regarding the nature of these tumors.

The term carcinosarcoma implies a mixed malignant tumor that is composed of an epithelial element, typically the common form of carcinoma seen in the tissue harboring the neoplasm, close to or intermixed with a sarcomatous component. The mixed nature of these tumors is confirmed by a positive immunohistochemical staining for both cytokeratins and vimentin. The common denominator of all carcinosarcomas is the lack of staining of the sarcomatous component for epithelial markers. On the contrary in the cases where both the sarcomatous and carcinomatous components are stained positively for epithelial markers the term “sarcomatoid carcinoma” should be addressed[2,3]. For all practical purposes in our review we consider carcinosarcomas as only cases where the sarcomatous component was stained negative for epithelial markers, irrespective of the term an author decided to utilize for describing the mixed tumor encountered.

The earliest report of a possible, due to lack of immunohistochemistry, carcinosarcoma can be tracked back to 1864 by Virchow[4]. These neoplasms usually arise in the female reproductive tract, urinary tract, the head and neck areas, breast and respiratory tract. The gastrointestinal tract is an uncommon location of carcinosarcomas, the esophagus being the most common location within it[1-4]. To our knowledge, only 7 cases of colonic carcinosarcomas have been reported in the English literature, and this case is the 8th. We report this case of rectal carcinosarcoma and review the literature on this rare malignancy.

A 60-years old male was admitted to our department for investigation of constipation and hypogastric discomfort intensified during defecation of a few weeks duration. He had a history of acute myocardial infarction and benign prostatic hyperplasia under medical treatment.

Abdominal and chest clinical examinations were unrevealing. However on digital examination a rubbery, fixed polypoid mass could be palpated just proximal to the dentate line. The complete blood count revealed only a slight anemia. Blood biochemistry was unrevealing.

On colonoscopy the mass was confirmed and a smaller polyp of 0.4 cm in diameter was detected on the upper rectum. Biopsies were obtained, which resulted in the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was subsequently performed revealing the lower rectal mass and distortion of adjacent perirectal fat. No metastatic foci to the liver or the abdominal cavity could be detected. The CXR was normal.

An abdominoperineal resection was performed. On intraoperative abdominal inspection and palpation, no abnormal findings could be detected asides from the pelvic mass. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on the 10th d.

The resected specimen, measuring 34 cm in length, consisted of anus, anal canal, rectum and sigmoid colon. The surgical margins were tumor free. The rectal tumor had a diameter of 7 cm, was elastic on palpation and had a whitish-yellow cut surface.

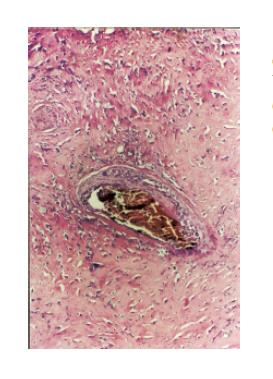

Histological examination revealed an invasive tumor infiltrating the full thickness of the rectal wall, as well as the perirectal fat and external sphincteric muscle fibers at the level of anal canal. The tumor consisted of poorly differentiated carcinomatous and spindle-shaped sarcomatous elements. Extensive areas of necrosis and hyaline degeneration of the stroma were evident. In a few locations the carcinomatous cells were organized into tubular and cribiform structures. 24 lymph nodes were recognized in the resected specimen. Five of them were positive for malignancy. The carcinomatous element was predominant, but sarcomatous cells could also be detected within the involved lymph nodes. The immunohistochemical profile is listed on Table 1. The final histologic diagnosis was rectal carcinosarcoma, TNM stage III.

| marker | carcinomatous | sarcomatous |

| Cam 5,2 | + | - |

| MNF 116 | + | - |

| Vimentin | - | + |

| Actin | - | + |

| S 100 | - | - |

| Chromogranin | - | - |

| c Kit | - | - |

| CD 34 | - | - |

| HER2/neu | - | - |

| Ki 67 | - | - |

| P53 | + | - |

Postoperatively the patient received 4 cycles of 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin chemotherapy. Follow-up radiological examination revealed a 16cm x 17cm hepatic metastatic focus as well as lung and peritoneal implants, local recurrence in the resection field and inguinal lymph node involvement, evident by the 4th postoperative month. Pelvic and inguinal radiotherapy was added. The patient finally succumbed to its disease at the 6th postoperative month. A postmortem examination was not performed.

Carcinosarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract are extremely rare. Most of them occur in the esophagus; about 40 cases have been reported in the gallbladder and less than 30 in the stomach. In a review of the English literature we found only seven immunohistochemicaly confirmed cases of carcinosarcoma of the large intestine, our case being the eighth[1-7]. Four further reports exist regarding colonic sarcomatoid carcinomas that should not be confused with carcinosarcomas, when purely immunohistochemical criteria are employed[8-11]. However the clinical relevance of this distinction is doubtful because the biological behavior of these neoplasms appears to be similar. In three other cases of colonic biphasic tumors the exact nature of the neoplasm is not clear.[12-14] The cases of colonic carcinosarcoma reported in the English literature are listed on Table 2.

| Case | Author | Age/Sex | Location | Histology | TNM Stage | Recurrence | Adjuvant | Survival (Mo) |

| 1 | Weidner (1986) | 73/M | Sigmoid | SCC+AC+OS+CS | II | Liver, LN, pelvis | Postop 5-FU, mitomycin C cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin | 49, died |

| 2 | Chetty (1993) | 72/F | Cecum | AC + UDSCS +RMS | IV | ? | No | 3, lost |

| 3 | Roncaroli (1995) | 71/F | Anorectum | NEC + RMS | II | Pelvis | Preop radiotherapy | 6, died |

| 4 | Takeyoshi (2000) | 82/M | Anorectum | AC + UDSCS | II | Skin | No | 6,died |

| 5 | Nakao (1998) | 60/F | Transverse | AC + RMS | III | - | Postop 5-FU+cisplatin | 14, disease free |

| 6 | Ishida (2003) | 80/F | rectosigmoid | AC+SCSM-N | III | Pelvis | No | 6, died |

| 7 | Aramendi (2003) | 84/M | Splenic flexure | AC+OS+CS | II | - | No | Died at diagnosis |

| 8 | Present case | 60/M | Rectum | AC+SCSM | III | Liver, Lung, pelvis, LN, peritoneum | Postop 5-FU, leucovorin and radiotherapy | 6, died |

Colonic carcinosarcomas present in the age group of 60 to 84 years, averaging 73 years of age at diagnosis. Males and females are equally affected. The tumor can be located anywhere in the large bowel, but a left-sided predominance is evident (six out of eight cases).

Histologically colonic carcinosarcomas are composed of two parts, an epithelial component and a mesenchymal component. The epithelial component appears indistinguishable from colonic adenocarcinoma. The malignant mesenchymal component of the tumor may be differentiated or undifferentiated. The differentiated is described as homologous or heterologous. Homologous elements resemble fibrosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma. If the sarcomatous part contains elements not normally found in the colon (e.g., cartilaginous, osseous, or rhabdomyoblastic), it is then described as heterologous. As stated in carcinosarcomas of other organs, the quality of the sarcomatous component does not appear to affect prognosis[1-3].

The possible histogenesis of colonic carcinosarcomas is a matter of debate. Several theories have been proposed to explain the histologic features of these tumors. These include the “collision tumor theory” suggesting that the two tumor components are derived from separate and distinct malignant cell clones. In favor of this opinion are investigators that observed sharply defined epithelial and sarcomatous components without demonstrable cells showing shared or transitional features on ultrastructural or immunohistochemical examination. Others propose a common origin of both components of carcinosarcomas, since common characteristics, epithelial in nature, between the different cellular populations as well as a transitional population could be observed. This could be either due to a malignant transformation of a pluripotential stem cell capable of both epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation (the combination theory) or due to a sarcomatoid/carcinomatous differentiation of a carcinoma/sarcoma (the conversion theory). Regarding the conversion theory it is believed that the carcinomatous element is the tumor’s “driving force”, and the sarcomatous component derives from this as a result of dedifferentiation. Some postulate that this sarcomatoid transition of carcinomatous cells could be related to an infection by a retrovirus[2,10]. Another theory that has been proposed to explain the presence of sarcomatous elements in carcinosarcomas questions the neoplastic nature of this component. According to this theory the sarcomatous component is a benign reparative or granulomatous tissue mass representing a conspicuous connective tissue response to the carcinoma, i.e. an epithelial-stromal interaction (the composition theory).

Evidence coming from studies on esophageal, breast, endometrial and uterine carcinosarcomas suggests that the combination or conversion theories, which are not mutually exclusive, are the prime nodes of histogenesis of these tumors, i.e. most carcinosarcomas are monoclonal and should be better considered as metaplastic carcinomas[1-4,15]. It is of interest to note that most lymph node metastases reflect the carcinomatous component. This adds to the hypothesis that the carcinomatous component is the driving force of these tumors, but this is not always the case. In our case one lymph node was infiltrated by both elements.

Over the recent years the increasing use of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy has added to our understanding of these tumors. However the information gathered was proved to be insufficient. Systematic genetic analysis may be the clue for understanding the pathogenesis of these mysterious tumors. Recently great interest has been shown on p53 status of these tumors. It has been suggested that the transition of carcinoma to sarcoma is associated with progressive accumulation of p53 proteins in this component[10]. However in our case this could not be confirmed since only the carcinomatous element stained positive for p53. Others have demonstrated the same p53 mutations on both sarcomatous and carcinomatous elements. Furthermore reports indicating no p53 mutation detection have been published[16,17](Figures 1 and 2).

The same diagnostic and operative treatment options that apply for colonic adenocarcinoma are also employed in the case of colonic carcinosarcomas, since no carcinosarcoma-specific treatment guidelines exist. All the reported cases of colonic carcinosarcomas underwent resection of the primary tumor and draining lymph nodes in the course of typical colectomies. Adjuvant therapy was added in four cases, consisting of chemotherapy in three and irradiation in two, but the efficacy of this approach remains questionable. However it should be noted that none of the patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy survived more than 6 mo, while the 2 cases that survived more than 6 mo had received postoperative chemotherapy[1-7].

The prognosis of carcinosarcomas is very poor. These tumors are very aggressive neoplasms characterized by rapid growth and a high incidence of both local recurrence and distant spread. Six of the eight reported cases died of the disease within 5 years of diagnosis. Survival ranged from 0 to 49 mo averaging 12 mo. For the remaining two cases there are no available data concerning their 5 year survival. These patients were reported to be alive at 3 and 14 mo postoperatively respectively, but only the patient that was alive at 14 mo was apparently “disease free”. Due to the lack of sufficient amount of cases no safe conclusions regarding prognostic factors can be made. Interestingly the stage of the disease does not appear to provide accurate information about prognosis since all four patients with reportedly stage II disease died within five years. Three of them were dead by the sixth postoperative month[1-7].

In general colonic carcinosarcomas constitute a rare category of malignant neoplasms whose nature is still incompletely understood. No specific treatment guidelines exist. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment and regardless of the addition of adjuvant therapy the prognosis is very poor. However some state that these neoplasms may be commoner than reported. This is due to the fact that the sarcomatous and carcinomatous elements are arranged unevenly at separate areas of the tumor, resulting in common preoperative and possible postoperative misdiagnosis if the specimen is not thoroughly examined. Careful examination of the resected colonic specimens may be the cornerstone of preventing underdiagnosis of these tumors and allow accumulation of knowledge to guide proper therapeutic intervention.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhang JZ E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Nakao A, Sakagami K, Uda M, Mitsuoka S, Ito H. Carcinosarcoma of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:276-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aramendi T, Fernández-Aceñero MJ, Villanueva MC. Carcinosarcoma of the colon: report of a rare tumor. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:345-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ishida H, Ohsawa T, Nakada H, Hashimoto D, Ohkubo T, Adachi A, Itoyama S. Carcinosarcoma of the rectosigmoid colon: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:545-549. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Takeyoshi I, Yoshida M, Ohwada S, Yamada T, Yanagisawa A, Morishita Y. Skin metastasis from the spindle cell component in rectal carcinosarcoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1611-1614. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Weidner N, Zekan P. Carcinosarcoma of the colon. Report of a unique case with light and immunohistochemical studies. Cancer. 1986;58:1126-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chetty R, Bhathal PS. Caecal adenocarcinoma with rhabdoid phenotype: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roncaroli F, Montironi R, Feliciotti F, Losi L, Eusebi V. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the anorectal junction with neuroendocrine and rhabdomyoblastic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Isimbaldi G, Sironi M, Assi A. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the colon. Report of the second case with immunohistochemical study. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:483-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Di Vizio D, Insabato L, Conzo G, Zafonte BT, Ferrara G, Pettinato G. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the colon: a case report with literature review. Tumori. 2001;87:431-435. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kim JH, Moon WS, Kang MJ, Park MJ, Lee DG. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the colon: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:657-660. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shoji M, Dobashi Y, Iwabuchi K, Kuwao S, Mikami T, Kameya T. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the descending colon--a histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Acta Oncol. 1998;37:765-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shah S, Kim DH, Harster G, Hossain A. Carcinosarcoma of the colon and spleen: a fleshy purple mass on colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bertram P, Treutner KH, Tietze L, Schumpelick V. True carcinosarcoma of the colon. Case report. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1997;382:173-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Conzo G, Giordano A, Candela G, Insabato L, Santini L. Colonic carcinosarcoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:748-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Iwaya T, Maesawa C, Tamura G, Sato N, Ikeda K, Sasaki A, Othuka K, Ishida K, Saito K, Satodate R. Esophageal carcinosarcoma: a genetic analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:973-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shih IeM, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1511-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 873] [Cited by in RCA: 926] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |