Published online Feb 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1265

Revised: October 3, 2005

Accepted: October 9, 2005

Published online: February 28, 2006

AIM: To study the therapeutic effect of interferon (IFN) and ribavirin with zinc supplement on patients with chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection.

METHODS: A total of 102 patients confirmed histologically to have chronic HCV infection with genotype 1b and more than 100 KIU/mL of HCV were randomly assigned to each arm of the study and each received 10 million units of pegylated interferon (IFN-alpha-2b) daily for 4 wk followed by the same dose every other day for 20 wk plus ribavirin (600 or 800 mg/d depending on body weight), with or without polaprezinc (150 mg/d) orally for 24 wk. The primary endpoint was sustained virological response (SVR) defined as negative HCV-RNA in the serum 6 mo after treatment.

RESULTS: There were no differences in the clinical background between the two groups except for more females in the dual therapy group than in the other group (P< 0.05). SVR was observed in 33.3% of the triple therapy group and 33.3% of the dual therapy group. The side effects were almost the same in both groups except for gastrointestinal symptoms, which were less in the triple therapy group (P = 0.019).

CONCLUSION: Considered together, triple therapy of zinc plus IFN and ribavirin for HCV infection patients with genotype 1b and high viral load is not better than dual therapy except for lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

- Citation: Suzuki H, Takagi H, Sohara N, Kanda D, Kakizaki S, Sato K, Mori M. Triple therapy of interferon and ribavirin with zinc supplementation for patients with chronic hepatitis C: A randomized controlled clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(8): 1265-1269

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i8/1265.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1265

Chronic hepatitis C is a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. It has become the most common indication for liver transplantation in many centers[1,2]. Improvement of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic HCV infection has been recently achieved by the introduction of pegylated interferon (IFN-alpha-2b) combined with ribavirin[3-5]. Because the sustained virological response rate in patients with HCV genotype 1b and high viral load is still insufficient, the search continues for new treatment strategies.

On the other hand, patients with chronic liver disease exhibit metabolic imbalances of trace elements such as high levels of iron and copper, and low levels of zinc, selenium, phosphorus, calcium and magnesium[6] . Of these trace elements, zinc is a constituent of a number of enzymes involved in a large number of metabolic processes. Mild-to-severe zinc deficiency disturbs several biological functions such as gene expression, protein synthesis, immunity, skeletal growth and maturation, gonad development, pregnancy outcomes, taste perception and appetite[7,8]. Zinc has been studied for its antiviral effects on HIV [9], rhinovirus[10] and herpes virus[11]. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, zinc has an antioxidant effect[12] and induces metallothionein (MT) which has radical scavenging and immunomodulatory effects[13]. Because zinc has many beneficial effects on viral eradication, we performed a preliminary study which showed the beneficial effect of IFN combined with zinc supplementation on chronic hepatitis C [14,15]. Here we present the results of a randomized controlled study of IFN with or without zinc supplementation for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C.

Adult patients of both genders aged 24 - 70 years with compensated chronic HCV infection were chosen. Each of the recruited patients fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: genotype 1b, more than 105 copies/mL of HCV in the serum, elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration for at least 6 mo before initiation of treatment, and a liver biopsy specimen taken in the preceding 6 mo of study entry showing chronic hepatitis. Patients were excluded when they suffered from any of the following conditions: decompensated liver disease, other causes of liver disease such as hepatitis B infection, autoimmune disorders, hemoglobin value < 11 g/dL, white blood cell count < 3/nL, thrombocytopenia < 70/nL, neoplastic disease, severe cardiac disease, other severe concurrent diseases such as preexisting psychiatric conditions, and pregnancy or lactation. Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study after a thorough explanation of the aims, risks and benefits of this therapy.

This randomized trial was conducted between January 2001 and December 2003 at 13 hospitals in Gunma, Japan. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to two study treatment groups with a ratio of 1:1 without stratification. Patients who met the entry criteria were randomly allocated into one of the two groups. The first group (triple therapy group) received oral triple therapy of 75 mg polaprezinc twice daily (Plomac; Zeria Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), IFN-alpha-2b (Intron A; Schering-Plough, Tokyo), and 600 mg or 800 mg ribavirin per day adjusted according to body weight (600 mg for weight below 60 kg and 800 mg for weight ≥60 kg) for 24 wk. The second group (dual therapy group) received combination therapy of IFN-alpha-2b and ribavirin at doses similar to those listed above, but no zinc supplementation. Since 75 milligrams of polaprezinc contained 17 mg of zinc, the patients received 34 mg of zinc per day. All patients were intramuscularly injected with 10 million units of IFN every day for 4 wk followed by three times a week for 20 wk. Patients were followed-up for another 24 wk after the treatment, i.e., until week 48.

The response to treatment was assessed as follows. Sustained virological response (SVR) was defined as undetectable HCV RNA in serum at the end of follow-up by analysis with Ampliform HCV version 2 with a lower limit of detection of 100 copies/mL. Analyses were performed in all patients who were randomized to one of the treatment groups. All the other patients whose HCV-RNA was positive 24 wk after the treatment were classified as non-responders.

In all patients, a liver biopsy was performed in the preceding 6 mo before therapy. Hepatic inflammation (grade) and fibrosis (stage) were assessed by the semiquantitative histological score proposed by Scheuer[16] and Desmet et al[17]. Portal/periportal inflammatory activity, lobular inflammatory activity and degenerative liver cell changes were scored using a scale of 0 to 3 for the criterion of inflammatory activity (1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: severe). The degree of fibrosis was scored using a scale of 0 to 4 (0: absent, 1: mild without septa, 2: moderate with a few septa, 3: numerous septa without cirrhosis, 4: cirrhosis).

Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) for frequency tables were used for statistical analysis. A logistic multiple regression model was used to examine relationships between baseline clinical characteristics and the binary outcome of response to therapy. Each variable was transformed into categorical data consisting of two simple ordinal numbers for the logistic multiple regression model. Variable selection was an important step in characterizing prognostic relations and identifying variables most strongly related to the outcome. The final model was then obtained by fitting only the main effect terms. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted by the StatView 5.0 and SAS version 8.2 statistical analysis packages.

We recruited 102 patients with genotype 1b and more than 100 KIU/mL of HCV-RNA who met the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The clinical background of the two treatment groups was not different except for gender (Table 1).

| Triple therapygroup | Dual therapygroup | P value | |

| Demography | |||

| Male/Female | 24/26 | 38/14 | 0.0151 |

| Agea (yr) | 57±23 (27-69 ) | 53.8±9.8 (23-70) | NS2 |

| Body weighta (kg) | 60.5±9.8 (35-93) | 63.5±12.4 (35-93) | NS2 |

| BMIa (kg/m2) | 23.5±3.1 | 23.4±2.1 | NS2 |

| Naïve/Retreatment | 34/15 | 40/11 | NS1 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| HCV RNA (kcopy/mL) | 700 (100-1490) | 720 (110-2310) | NS2 |

| ALTa (U/L) | 95.6±61.1 | 97.4±59.8 | NS2 |

| Ferritina | 216.8±244.4 | 214±139.6 | NS2 |

| Serum zinca (μg/dL) | 73.3±20.3 | 69.8±17.2 | NS2 |

| Histopathology | |||

| F 0/1/2/3/4 | 3/12/23/10/1 | 1/20/15/13/1 | NS1 |

| A 1/2/3 | 26/20/2 | 20/24/5 | NS1 |

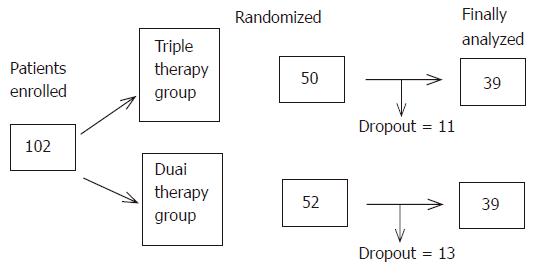

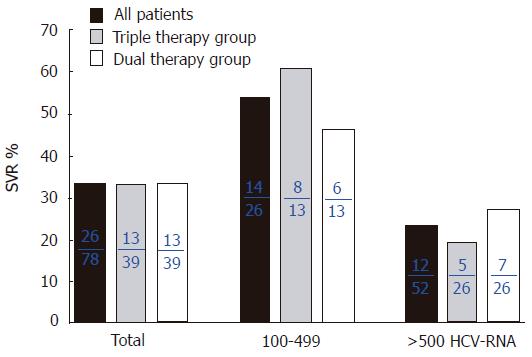

Twenty-four patients dropped out because of side effects and inability of follow-up due to unknown reasons. Thus, 78 patients including 39 patients on triple therapy and 39 who did not receive zinc supplementation were the subjects of this study (Figure 1). At the end of the study (48 wk), the SVR rate was 33.3% (13/39) in both the dual therapy and triple therapy groups (Figure 2). One week after the beginning of treatment, the viral disappearance rate in the triple therapy group (20.0% [5/25]) was not significantly different from that in the dual therapy group (10.3% [3/29]). Four weeks after the beginning of treatment, the viral disappearance rate in the triple therapy group was 69.7% (23/33), which was not significantly different from that in the dual therapy group (57.1% [16/28]). While there were no significant differences between the two groups, patients of the triple therapy group tended to show an earlier decrease of the viral load compared to the dual therapy group (Table 2).

| HCV RNA(kcopy/mL) | Triple therapy group | Dual therapy group | ||||||

| 1wk | 4wk | 24wk | 48wk | 1wk | 4wk | 24wk | 48wk | |

| >500 | 1/17 | 13/21 | 21/26 | 5/26 | 1/20 | 10/20 | 25/26 | 7/26 |

| 5.9% | 61.9% | 69.2% | 19.2% | 5.0% | 50.0% | 96.2% | 26.9% | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| 100-499 | 4/8 | 10/12 | 13/13 | 8/13 | 2/9 | 6/8 | 13/13 | 6/13 |

| 50.0% | 83.3% | 100% | 61.5% | 22.2% | 75.0% | 100% | 46.2% | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| All patients | 5/25 | 23/33 | 34/39 | 13/39 | 3/29 | 16/28 | 38/39 | 13/39 |

| 20.0% | 69.7% | 87.2% | 33.3% | 10.3% | 57.1% | 97.4% | 33.3% | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||

With regard to HCV-RNA load in the serum, the SVR rate of patients with HCV-RNA between 100 and 499 KIU/mL was 64.3% (8/13) in the triple therapy group, which was not different from that in the dual therapy group (46.2% [6/13]). Similarly, the SVR rate of patients with HCV-RNA >500 KIU/mL was not significantly different between the triple therapy and dual therapy groups (5/26 [19.2%] and 7/26 [26.9%], respectively).

A logistic multiple regression model was used for statistical analysis including HCV-RNA, body weight and pre-treatment platelet count. The analysis identified HCV-RNA level as a significant determinant of SVR when data of both groups were pooled together (Table 3).

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| HCV RNA (kcopy/mL) | |||

| <500 | 1.000 | 0.014-0.690 | 0.0197 |

| ≥500 | 0.097 | ||

| Body weight (kg) | |||

| <64 | 1.000 | 0.931-63.301 | 0.0583 |

| ≥64 | 7.677 | ||

| Pre-treatment platelet count (×104/μL) | |||

| <16 | 1.000 | 0.032-1.909 | 0.1798 |

| ≥16 | 0.246 | ||

The side effects of the treatment were almost the same in both groups, including flu-like symptoms, mild reduction in hemoglobin, mild thrombocytopenia and leukopenia (Tables 4 and 5). The number of dropouts due to adverse effects was similar in the two groups (11 of 50 in the zinc group and 13 of 52 in the control group). The main reasons for dropout were anemia, fatigue, appetite loss and psychosomatic complaints (Table 6). The treatment protocol did not correlate significantly with the number of cases with adverse effects listed in Tables 4-6 except for abdominal discomfort. Fewer patients of the triple therapy group developed this side effect than those of the other group (P = 0.019, Table 4).

| Triple therapy group | Dual therapy group | ||

| Fever | 35 (89.7) | 38 (97.4) | NS |

| Anorexia | 26 (66.7) | 25 (64.1) | NS |

| Fatigue | 24 (61.5) | 22 (59.0) | NS |

| Arthralgia | 20 (51.3) | 18 (46.1) | NS |

| Eczema | 16 (41.0) | 13 (33.3) | NS |

| Nausea | 14 (35.9) | 13 (33.3) | NS |

| Abdominal discomfort | 8 (20.5 ) | 18 (46.2) | P < 0.019 |

| Stomatitis | 13 (33.3) | 12 (30.8) | NS |

| Headache | 11 (28.2) | 14 (35.9) | NS |

| Hair loss | 12 (30.8) | 7 (17.9) | NS |

| Psychosomatic | 3 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) | NS |

| Triple therapy group | Dual therapy group | ||

| Decrease in WBC (<2 000 μL) | 5 | 5 | NS |

| (<1 500 μL) | 1 | 0 | NS |

| Decrease in hemoglobin (> 10 g/dL) | 13 | 14 | NS |

| (>8.5 g/dL) | 3 | 4 | NS |

| Decrease in platelet count (<50 000 μL) | 1 | 3 | NS |

| IFN dose reduction | 9 | 10 | NS |

| Ribavirin dose reduction | 15 | 17 | NS |

The metabolism of trace elements is distorted in chronic liver disease[6]. We have previously reported that zinc deficiency in patients with chronic HCV can be improved by treatment with IFN[18]. In our previous pilot study, the beneficial effects of combined treatment of zinc and IFN have been confirmed with regard to both eradication of the virus and lowering or normalization of ALT[15].

In view of the clinical background of patients before treatment, the number of female patients in our study was greater than that of male patients in the triple therapy group, but univariate analysis did not reveal a significant sex difference in the effect of treatment.

Although patients on triple therapy showed early disappearance of HCV-RNA, the results 24 wk after the treatment showed no overall beneficial effect of zinc supplementation and are similar to those of previous reports[15]. Furthermore, the triple therapy tended to have the same beneficial effects of IFN + ribavirin dual therapy in patients with moderate viral load (between 100 and 499 KIU/mL). It is possible that longer treatment (more than 24 wk) and perhaps higher dosages of IFN and ribavirin may produce different results. Based on the adverse effects of the treatment, the only advantage of the triple therapy is the significantly lower incidence of abdominal discomfort compared to the dual therapy.

Polaprezinc, a synthetic agent, N- (3-aminopropionyl)-L-histidinate zinc, is a chelating compound for ulcer healing and has been used experimentally to prevent gastric ulceration in rats as well as clinically as an antipeptic ulcer drug[19,20]. Zinc present in the orally administered polaprezinc is absorbed, leading to a rise in serum concentration of zinc[21]. In this respect, absorption of polaprezinc is more favorable than other zinc-containing derivatives such as zinc sulfate[21] . While the dose of polaprezinc could increase serum zinc concentration and possibly improve the SVR, caution should be exercised with regard to the side effects of higher doses of polaprezinc, as it is known to induce abdominal discomfort in some patients (personal communication).

In conclusion, 24-wk zinc supplementation has no additive effect on the anti-HCV dual therapy of IFN-alpha-2 and ribavirin, apart from reducing the incidence of abdominal discomfort.

This study was performed by Gunma Liver Study Group, Japan.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | 1 Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 1998;351:351-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marcellin P. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of the disease. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4747] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, O'Grady J, Reichen J, Diago M, Lin A. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 883] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Loguercio C, De Girolamo V, Federico A, Feng SL, Cataldi V, Del Vecchio Blanco C, Gialanella G. Trace elements and chronic liver diseases. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 1997;11:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aggett PJ. Severe zinc deficiency. Zinc in Human Biology. New York: Springer-Verlag 1989; 259-279. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Umeta M, West CE, Haidar J, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG. Zinc supplementation and stunted infants in Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:2021-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haraguchi Y, Sakurai H, Hussain S, Anner BM, Hoshino H. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by zinc group metal compounds. Antiviral Res. 1999;43:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Novick SG, Godfrey JC, Pollack RL, Wilder HR. Zinc-induced suppression of inflammation in the respiratory tract, caused by infection with human rhinovirus and other irritants. Med Hypotheses. 1997;49:347-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kümel G, Schrader S, Zentgraf H, Brendel M. [Therapy of banal HSV lesions: molecular mechanisms of the antiviral activity of zinc sulfate]. Hautarzt. 1991;42:439-445. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Prasad AS. Zinc and immunity. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;188:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nagamine T, Takagi H, Takayama H, Kojima A, Kakizaki S, Mori M, Nakajima K. Preliminary study of combination therapy with interferon-alpha and zinc in chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1b. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2000;75:53-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Takagi H, Nagamine T, Abe T, Takayama H, Sato K, Otsuka T, Kakizaki S, Hashimoto Y, Matsumoto T, Kojima A. Zinc supplementation enhances the response to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol. 1991;13:372-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1130] [Cited by in RCA: 1197] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1582] [Cited by in RCA: 1506] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nagamine T, Takagi H, Hashimoto Y, Takayama H, Shimoda R, Nomura N, Suzuki K, Mori M, Nakajima K. The possible role of zinc and metallothionein in the liver on the therapeutic effect of IFN-alpha to hepatitis C patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1997;58:65-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arakawa T, Satoh H, Nakamura A, Nebiki H, Fukuda T, Sakuma H, Nakamura H, Ishikawa M, Seiki M, Kobayashi K. Effects of zinc L-carnosine on gastric mucosal and cell damage caused by ethanol in rats. Correlation with endogenous prostaglandin E2. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:559-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miyoshi A, Matsuo H, Miwa G, Nakajima M. Clinical evaluation of Z-103 in the treatment of gastric ulcer. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 1992;20:181-197. |

| 21. | Sano H, Furuta S, Toyama S, Miwa M, Ikeda Y, Suzuki M, Sato H, Matsuda K. Study on the metabolic fate of catena-(S)-[mu-[N alpha-(3- aminopropionyl)histidinato(2-)-N1,N2,O: N tau]-zinc]. 1st communication: absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion after single administration to rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41:965-975. [PubMed] |