Published online Feb 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1255

Revised: October 29, 2005

Accepted: October 26, 2005

Published online: February 28, 2006

AIM: To investigate the prevalence and clinical significance of “anti-HBc alone” in an unselected population of patients and employees of a university hospital in southern Germany.

METHODS: All individuals with the pattern “anti-HBc alone” were registered over a time span of 82 mo. HBV-DNA was measured in serum and liver samples, and clinical charts were reviewed.

RESULTS: Five hundred and fifty two individuals were “anti-HBc alone” (of 3004 anti-HBc positive individuals; 18.4%), and this pattern affected males (20.5%) more often than females (15.3%; P < 0.001). HBV-DNA was detected in serum of 44 of 545 “anti-HBc alone” individuals (8.1%), and in paraffin embedded liver tissue in 16 of 39 patients tested (41.0%). There was no association between the detection of HBV genomes and the presence of biochemical, ultrasonic or histological signs of liver damage. Thirty-eight “anti-HBc alone” patients with cirrhosis or primary liver carcinoma had at least one additional risk factor. HCV-coinfection was present in 20.4% of all individuals with “anti-HBc alone” and was the only factor associated with a worse clinical outcome.

CONCLUSION: In an HBV low prevalence area, no evidence is found that HBV alone causes severe liver damage in individuals with “anti-HBc alone”. Recommendations for the management of these individuals are given.

- Citation: Knöll A, Hartmann A, Hamoshi H, Weislmaier K, Jilg W. Serological pattern “anti-HBc alone”: Characterization of 552 individuals and clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(8): 1255-1260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i8/1255.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1255

Antibodies to hepatitis B virus (HBV) core antigen (anti-HBc) are the most important marker of HBV infection. They are present when symptoms of hepatitis first appear and usually persist for life, irrespective if the infection resolves or remains chronic. Complete recovery from acute and chronic hepatitis B is associated with the loss of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and appearance of HBsAg-specific antibodies (anti-HBs) in serum. Thus, anti-HBc is usually accompanied by HBsAg or anti-HBs. However, the detection of “anti-HBc alone” (as the only marker of HBV infection) is not an infrequent serological pattern. In areas with low HBV prevalence (most parts of Europe and the United States) “anti-HBc alone” is found in 10-20% of all individuals with HBV markers, according to 1-4% of the general population[1,2]. This pattern poses problems because it provides no exact diagnosis. It is seen in acute infections, in the interval between the loss of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs, as well as in chronic and past infections. Some individuals with “anti-HBc alone” carry HBV in their serum, their proportion varies greatly between 0.2% in blood donors and 47% in iv drug abusers[1].

The clinical significance of “anti-HBc alone” is greatly unknown. Longitudinal studies to explore the long-term clinical outcome are hardly practicable. We therefore investigated all individuals found positive for “anti-HBc alone” in our diagnostic laboratory over a period of 82 mo in regard to their virological and clinical findings.

From July 1996 through April 2003, all individuals were registered whose sera tested reactive for anti-HBc and negative for HBsAg and anti-HBs for the first time. Our laboratory routinely received samples from patients and employees of a University hospital in Southern Germany. Totally 552 individuals (≥12 mo of age) with reactivity to “anti-HBc alone” were included in a database, and results of previous or follow-up testing for HBV markers were added when available for the study period. Clinical charts were reviewed to collect data about the medical history and clinical status of each individual.

HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc, and anti-HBe were tested with microparticle enzyme immunoassays (AxSYM HBsAgTM, AxSYM AUSABTM, AxSYM CORETM, AxSYM Anti-HBeTM; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Reactivity to “anti-HBc alone” (HBsAg and anti-HBs negative) was confirmed with a second microparticle enzyme immunoassay (IMx Core, Abbott, Delkenheim, Germany). When the new chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay ARCHITECT anti-HBcTM (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) became available, all newly identified “anti-HBc alone” patients were additionally tested with this assay if there was enough serum available (n = 113).

Antibodies against HCV and HIV were measured with microparticle enzyme immunoassays (AXSYM HCVTM, AXSYM HIV-1/ HIV-2TM; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Positive test results were confirmed with Western blot assays Abbott MATRIX HCV 2.0 (Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesbaden-Dielkenhein, Germany) and NEW LAV BLOT I and II (BIORAD Laboratories, Munich, Germany), respectively.

HBV-DNA was isolated from serum with the QIAmpTM blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Paraffin embedded liver tissue was available for 39 patients from liver biopsies (hepatitis C, n = 16; cirrhosis of the liver, n = 5; liver abscess, n = 2; deteriorating liver function after gastric perforation, n = 1) or from liver surgery (liver transplantation for HCV associated cirrhosis, n = 4; liver transplantation for alcohol associated cirrhosis, n = 3; hepatocellular carcinoma, n = 4; liver metastases, n = 2; thrombosis of the portal vein, n = 1; planned organ donation after brain death due to cerebral hemorrhage, n = 1). Five to ten 5-µm sections were deparaffined as described before[3] and DNA was prepared using the QIAmpTM blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). HBV-DNA was quantitatively measured using a kinetic fluorescence detection system (TaqMan PCR)[4]. The lower detection limit of this assay was 50-100 genomic copies per mL.

HCV-RNA in serum was detected using the Cobas Amplicor 2, 0 (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

The SPSS program package version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was utilized to perform Fisher’s exact test, χ2 test and t-test. The significance level was set at 5%, all Ps resulted from two-sided tests.

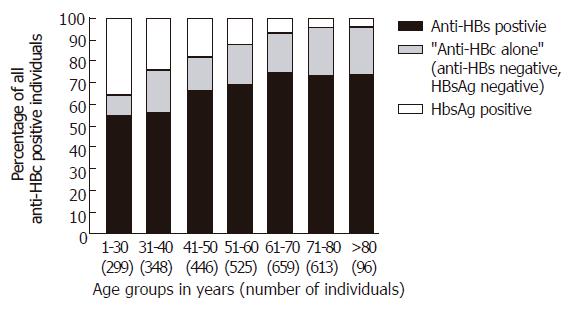

From July 1996 through April 2003, 3004 individuals tested positive for anti-HBc (Table 1) and 552 showed reactivity to “anti-HBc alone” (18.4%). “Anti-HBc alone” was seen more often in males (370/1806; 20.5%) than in females (180/1176; 15.3%; P < 0.001). The percentage of individuals positive for “anti-HBc alone” was highest in the age group 71-80 years (139/613; 22.7%) and lowest in the youngest group 1-30 years of age (28/299; 9.4%; Figure 1).

| HBsAg neganti-HBs neg | Anti-HBc posHBsAg posAnti-HBs neg | HBsAg neganti-HBs pos | Anti-HBc neg | |

| Study period | 82 mo (6/96-4/03) | 12 mo (1/03-12/03) | ||

| n (% of anti-HBc pos) | 552 (18.4 %) | 412 (13.7 %) | 2040 (67.9 %) | 4398 |

| Male/female (ratio) | 370/180 (2.06 : 1) | 251/145 (1.73 : 1) | 1185/851 (1.39 : 1) | 2631/1766 (1.49 : 1) |

| Age (yr; mean±SD) | 58.5 ± 16.5 | 42.8 ± 17.4 | 57.4 ± 16.7 | 50.4 ± 19.6 |

| Anti-HCV pos/n tested (%) | 112/550 (20.36 %) | 20/323 (6.19 %) | 144/1983 (7.26 %) | 95/4285 (2.22 %) |

| Anti-HIV pos/n tested (%) | 17/540 (3.15 %) | 8/206 (3.88 %) | 23/1571 (1.46 %) | 7/3768 (0.19 %) |

In 113 “anti-HBc alone” individuals, apart from the confirmatory test, an additional assay for anti-HBc was performed (ARCHITECTTM): anti-HBc was positive in 111 individuals, negative in one individual, and alternating negative and positive in two consecutive samples from another individual.

One hundred and twelve of 550 “anti-HBc alone” individuals (20.4%) were positive for anti-HCV. HCV-RNA was detected in 98 of 108 anti-HCV positive patients tested (90.7%). Five hundred and forty “anti-HBc alone” individuals were tested for anti-HIV and 17 (3.1%) were positive.

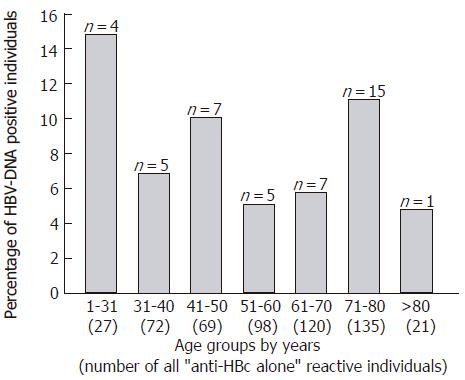

Sera from 545 “anti-HBc alone” individuals were tested for the presence of HBV-DNA by PCR and 44 were positive (8.1%). The viral load was between 50 (lower limit of detection) and 1000 copies/ml serum. The percentage of HBV-DNA positive individuals was highest in the youngest group 1-30 years of age (4/27; 14.8%) and lowest in the age group > 80 years (1/21; 4.8%; Figure 2).

Paraffin embedded liver tissue was available from 39 patients. HBV-DNA was detected in 16 (41.0%): in 12 of 32 liver samples (37.5%) which had originally been taken because a chronic liver damage was suspected, and in 4 of 7 liver samples (57.1%) taken for other reasons. Considering the results of the histological examination, HBV-DNA was detected in 2 of 17 livers with cirrhosis, in 3 of 9 primary liver cancers and in 11 of 13 livers without cirrhosis or primary carcinoma.

Only 2 of the 39 patients with available liver samples were HBV-DNA positive in serum: one patient with chronic hepatitis C (no cirrhosis or carcinoma) was HBV-DNA positive both in serum and liver, and one patient with hepatocellular carcinoma was HBV-DNA positive only in serum but not in liver. Thus, liver HBV-DNA was positive in 1 of 2 patients with serum HBV-DNA and in 15 of 37 patients without serum HBV-DNA.

The 552 “anti-HBc alone” individuals were initially tested for HBV markers due to the following reasons: routine screening prior to invasive procedures (n = 416); diagnostic evaluation of cirrhosis of the liver (n = 20), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 11), or elevation of transaminases (n = 10); diagnostic evaluation of a known HCV (n = 28) or HIV (n = 16) infection; routine screening of health care workers (n = 6); follow up evaluation of a known hepatitis B infection (n = 4); and evaluation of a needle stick injury recipient (n = 3). No diagnosis or cause of testing was given in 38 cases. In 90 patients (16.3%), the positive anti-HBc status was known prior to the actual investigation. Thirteen patients (2.4%) had suffered from jaundice of unknown origin earlier in their life. Information about suspected modes of infection or risk factors was available for 141 patients (25.5%): origin from an HBV hyperendemic area (n = 95), intravenous drug abuse (n = 21), HIV-infection (n = 17), previous blood transfusion or transplantation (n = 17), health care worker (n = 10), and HBV-positive sex partner (n = 4). Twenty individuals had more than one of these risk factors.

Alanine transaminase (ALT) activity was measured in 445 individuals and was normal in 279, up to twofold elevated in 89 and more than twofold elevated in 77 patients. Ultrasonic investigation of the liver was performed in 237 patients and revealed enlargement/steatosis of the liver in 69, signs of cirrhosis in 20, liver carcinoma in 10, and was non-distinctive in 20 patients. Histological examination of the liver was performed in 43 patients and showed cirrhosis in 16, hepatocellular carcinoma with cirrhosis in 10, active viral hepatitis in 8 (all with chronic HCV infection, HBV-DNA in serum positive in 1/8), steatosis of the liver in 3, liver abscess in 2, metastases of colon carcinoma in 2, primary biliary cirrhosis in one, and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma without cirrhosis in one patient.

Combining all results of clinical, ultrasonic and histological examinations, we identified 38 “anti-HBc alone” patients with severe chronic liver damage (cirrhosis of the liver, n = 27; hepatocellular carcinoma, n = 10; combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma, n = 1). All 38 patients had at least one additional risk factor capable of causing the severe liver damage: chronic HCV infection (n = 18), alcohol abuse (n = 14), combined alcohol abuse and HCV infection (n = 5), and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (n = 1).

“Anti-HBc alone” reactive individuals with positive and negative HBV-DNA in serum were compared regarding sex, age, ALT level, liver pathology, anti-HBs-titer, anti-HBe-status, HCV- and HIV coinfection. Statistically significant differences were not found (Table 2).

| HBV-DNA-PCR in serum1 | |||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| n | 44 | 501 | |

| Males/females2 | 27/17 | 336/163 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 57.2 ± 18.6 | 58.5 ± 16.2 | |

| ALT2 | Normal | 23/35 (65.7%) | 251/402 (62.4%) |

| ≤Twofold increase | 7/35 (20.0%) | 81/402 (20.1%) | |

| > Twofold increase | 5/35 (14.3%) | 70/402 (17.4%) | |

| Liver ultrasound2 | no pathological findings | 5/11 (45.5%) | 112/204 (54.9%) |

| Steatosis | 5/11 (45.5%) | 63/204 (30.9%) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0/11 | 20/204 (9.8%) | |

| Carcinoma | 1/11 (9.1%) | 9/204 (4.4%) | |

| Liver histology2 | No pathological findings | 0/2 | 5/42 (11.9%) |

| Viral inflammation | 1/2 (50%) | 7/42 (16.7%) | |

| Steatosis | 0 /2 | 3/42 (7.1%) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0 /2 | 17/42 (40.5%) | |

| Carcinoma | 1/2 (50%) | 10/42 (23.8%) | |

| Anti-HBs titer (IU/L) | 1.9 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 3.0 | |

| Anti-HBe pos/n tested | 6/9 (66.7%) | 53/138 (38.4%) | |

| Anti-HCV pos/n tested | 7/44 (15.9%) | 103/500 (20.6%) | |

| Anti-HIV pos/n tested | 0/43 (0 %) | 17/491 (3.5%) | |

In those patients investigated, the detection of anti-HCV antibodies was associated with an elevation of ALT activity (P < 0.001) and with the presence of cirrhosis or primary carcinoma of the liver (Table 3).

| Anti-HCV | P-value | |||

| Positive | Negative | |||

| Sex | Males | 76 | 290 | NS2 |

| Females | 36 | 141 | ||

| ALT1 | Normal | 31 | 244 | < 0.001 |

| ≤ Twofold increase | 20 | 67 | ||

| > Twofold increase | 48 | 29 | ||

| Liver ultrasound1 | No pathological findings | 27 | 89 | 0.03 |

| Steatosis | 25 | 43 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 11 | 9 | ||

| Carcinoma | 6 | 4 | ||

| Liver histology1 | No pathological findings | 0 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Viral inflammation | 8 | 0 | ||

| Steatosis | 2 | 1 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 12 | 4 | ||

| Carcinoma | 6 | 4 | ||

In 151 of the 552 “anti-HBc alone” patients (27.4%), more than one serum was investigated during the study period. In 111 individuals, reactivity to “anti-HBc alone” was confirmed by subsequent testing after a mean follow up period of 17.1 mo (minimum-maximum, 0-77 mo). Eleven individuals were anti-HBs positive (16.8 ± 8.4 IU/L) when retested after a mean of 11.5 months (1-38 mo), and 10 individuals had anti-HBs titers fluctuating slightly above and below 10 IU/L over a period of 44.9 mo (10-82 mo).

One “anti-HBc alone” patient (male, 45 years, HBV-DNA in serum positive) showed HBV reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg, HBeAg, increase of HBV-DNA and loss of anti-HBs - but normal ALT activity - after treatment with rituximab (humanized monoclonal antibody to CD 20) and chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

For 18 patients, a previous serum sample was available not showing the “anti-HBc alone” pattern. Twelve patients were anti-HBs positive (16.6 ± 4.7 IU/L) at an average of 31.3 mo (1-59 mo) before being detected as ”anti-HBc alone”.

Six patients were previously HBsAg positive. Three of them had an acute HBV infection recently: (1) one female patient (14 years old) lost HBsAg after 9 mo, but remained HBV-DNA positive and anti-HBs negative during an additional 34 mo; (2) one male patient (45 years old) was “anti-HBc alone” (HBV-DNA positive) 4 mo after the acute infection and tested anti-HBs-positive after additional 4 mo; (3) one male patient (17 years old) was “anti-HBc alone” (HBV-DNA negative) 4 mo after the acute infection and was anti-HBs positive when retested after an additional 10 mo. Two patients just cleared a chronic HBV infection: one male patient (37 years old) had a chronic HBV and HCV infection for at least 6 years and cleared HBsAg (but not HBV-DNA or HCV-RNA) after treatment with PEG-interferon and ribavirin; the other male patient (59 years old) was discovered to be HBsAg positive by routine screening (ALT normal, HBV-DNA negative), and was “anti-HBc alone” when retested after 5 mo. The sixth patient (male, 41 years old) showed reverse seroconversion (reappearance of HBsAg and loss of anti-HBs) and moderate ALT elevations 14 mo after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[5]. He lost HBsAg again after 4 mo and had alternating anti-HBs positive and negative (“anti-HBc alone”) but HBV-DNA negative during follow up (53 mo).

The present study has primarily been undertaken to assess the clinical significance of the serological pattern “anti-HBc alone”. Over a period of 6 years and 8 mo, 552 individuals with this pattern were identified in our laboratory, accounting for 18.4% of all individuals with positive anti-HBC. Forty-four of 545 “anti-HBc alone” patients had circulating HBV-DNA with less than 1 000 copies/ml. Depending on the sensitivity of the PCR assay, the proportion of HBV-DNA carriers in this study (8.1%; detection limit 50 HBV-DNA-copies/ml) complies with other studies reporting carrier rates of 3.3% and 7.7% (detection limits of 5 000 and 100 HBV-DNA copies/mL, respectively) in unselected German individuals or blood donors[2,6]. Even more “anti-HBc alone” individuals with very low viremia would probably be found if the sensitivity of the assay were increased. In paraffin embedded liver tissue, we detected HBV-DNA in 16/39 “anti-HBc an alone” patients (41.0%), only one of them was also PCR positive in serum. Thus, a significant fraction of “anti-HBc alone” individuals carry HBV genomes. However, HBV-DNA has also been detected in individuals with anti-HBs antibodies. Two German studies have reported a total of six HBV-DNA-positive blood donors with anti-HBs levels greater than 100 IU/L[7,8]. After the resolution of an HBV infection, a periodical release of virions from hepatocytes, as first described by Reherman et al[9], can occur in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc positive individuals, although more often in persons who lack anti-HBs compared to those with detectable anti-HBs[10].

The essential question about these “occult” infections applies to their clinical impact. Since HBV-DNA has been found in serum and liver samples of HBsAg-negative patients with cirrhosis or primary liver cancer[11-13], it has been suggested that “anti-HBc alone” individuals may suffer from chronic liver injury with the associated oncogenic potential. Herein, we identified 38 “anti-HBc alone” patients with severe chronic liver damage. All 38 patients had at least one other risk factor which could cause the liver damage by itself. In addition, HBV-DNA was less often detected in the liver of these patients (2/17 with cirrhosis, 3/9 with primary carcinoma) than in liver samples from patients without chronic liver damage (11/13). When all “anti-HBc alone” individuals of this study were analyzed, there was no association between the detection of HBV-DNA in serum and ultrasonic, histological or biochemical evidence of liver damage. Therefore, the present study provides no evidence that HBV alone causes liver damage in “anti-HBc alone” individuals.

Although an occult HBV infection in “anti-HBc alone” individuals seems to be inoffensive, it might become injurious in the case of immunosuppression leading to viral reactivation. In patients with past infection (anti-HBs and anti-HBc positive), HBV reactivation has been reported during chemotherapy, HIV infection, and after kidney and bone marrow transplantation[14-17]. In the present study, HBV reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg was observed in one “anti-HBc alone” patient after treatment with rituximab (humanized monoclonal antibody to CD 20) and chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This patient had no clinical hepatitis, but there are at least two reported cases of HBV reactivation with liver inflammation after rituximab and chemotherapy: one patient died from liver failure[18], and the other reactivation occurred in a patient with preexisting anti-HBs and anti-HBc antibodies[19]. Our findings justify the cautious use of rituximab in “anti-HBc alone” patients and emphasize that these patients carry the risk for HBV reactivation during immunosuppression in general.

When a patient is diagnosed to be reactive for “anti-HBc alone”, several explanations might apply to this phenomenon. First, a certain proportion of “anti-HBc alone” individuals will be false positive, depending both on the anti-HBc test used and on the HBV prevalence of the population investigated. We aimed to minimize false positives by including only individuals who were anti-HBc positive in a second confirmatory assay. When a subset of 113 individuals was investigated with a third anti-HBc test, reactivity was confirmed in 111 (98%). Although all three assays were from the same manufacturer, we estimated that the population was truly anti-HBc reactive. An alternative assay from a different manufacturer might provide a better confirmation, but there was no serum for additional assays available.

Second, “anti-HBc alone” individuals might be in the window phase of an acute HBV infection when HBsAg disappears followed by anti-HBs a few weeks later. Herein, only 6 of 552 “anti-HBc alone” individuals were known to be HBsAg positive before: three were in the window period after an acute infection, two probably just cleared a chronic infection, and one lost HBsAg again after HBV reactivation following bone marrow transplantation. In a low HBV prevalence area as in Germany, the proportion of “anti-HBc alone” individuals in the window period is very low, but individuals in this period are probably infectious.

Third, “anti-HBc” alone can also reflect an HBV infection which has resolved many years or decades earlier. In the majority of our patients, reactivity for anti-HBc was an incidental finding, most were healthy and not aware of a previous liver inflammation. In 151 of the 552 “anti-HBc alone” individuals, more than one sample was investigated during the study period: 12 individuals were anti-HBs positive before being detected as “anti-HBc alone”, 10 individuals had anti-HBs titers fluctuating around 10 IU/L during follow up, and 11 individuals were weakly anti-HBs positive when retested. These findings suggest that a significant proportion of “anti-HBc alone” individuals are comparable to those still showing anti-HBs.

Fourth, a large fraction of “anti-HBc alone” patients is assumed to have an unresolved chronic infection with low grade, possibly intermittent virus production. These individuals have detectable HBV-DNA in serum (8.1% in this study) and are potentially infectious. The negative HBsAg assay is unclear in these cases, but can be caused by very low concentrations of HBsAg, fixation of HBsAg in immune complexes, or by HBsAg mutations[20,21]. From a practical point of view, there seems to be no clear-cut distinction between “late immunity” and “unresolved infection”: HBV-DNA has also been detected in anti-HBs positive individuals, and HBV reactivation can occur both in anti-HBs positive and in “anti-HBc alone” patients. In the present study, there was no difference in the clinical picture between HBV-DNA negative and positive individuals with “anti-HBc alone”.

One final explanation for the phenomenon “anti-HBc alone” is the suppression of HBV replication by an HCV coinfection. In the present study, 112/550 “anti-HBc alone” individuals (20.4%) were coinfected with HCV, and patients with HCV coinfection more often had an elevated ALT activity or chronic liver damage. The detrimental effect of HCV coinfection has previously been reported in HBsAg positive patients with chronic HBV infection[22,23].

In conclusion, we performed an extensive study including 552 “anti-HBc alone” individuals of all age groups and found no single patient who had severe liver damage and no additional risk factor other than the “anti-HBc alone” pattern. There was also no association between the detection of HBV genomes in serum and/or liver and damage of the liver. Therefore, the probability that HBV alone causes severe liver damage in “anti-HBc alone” patients seems to be low.

This study supports suggestions for the practical management of “anti-HBc alone” individuals which have previously been made by a group of experts[1]: When this pattern is observed for the first time, a false positive anti-HBc reactivity should be ruled out by a second anti-HBc test, preferably an assay with a different format. In some cases, anti-HBe will also be present and confirm the authenticity of the hepatitis B markers. All “anti-HBc alone” individuals must be screened for an HCV coinfection. To search for a chronic HBV infection (or an infection in the window phase), viral DNA should be measured with the most sensitive DNA amplification method (capable of detecting ≤100 genomes per mL), and the ALT activity should be determined. It appears sufficient to re-evaluate individuals without HBV-DNA and with normal ALT level after a longer period of time, e.g. every five years. In case of a relevant ALT elevation, a liver biopsy seems appropriate to reach a conclusion concerning therapy. Antiviral treatment should be considered if HBV-DNA and biochemical and histological signs of active hepatitis are present. Since “anti-HBc alone” patients with this constellation are rare, they should be monitored by an experienced hepatologist. Individuals with positive HBV-DNA PCR and normal ALT values should be assessed in yearly intervals. When “anti-HBc alone” individuals are subjected to severe immunosuppression (e.g. during anti-tumor chemotherapy or transplantation), HBV-DNA assays should be applied to recognize viral reactivation. Individuals with “anti-HBc alone” must be advised not to donate blood.

Further research is needed to answer open questions about the pattern “anti-HBc alone”, e.g. concerning the reason for the male predominance and the infectivity of affected individuals.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhang JZ E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Grob P, Jilg W, Bornhak H, Gerken G, Gerlich W, Günther S, Hess G, Hüdig H, Kitchen A, Margolis H. Serological pattern "anti-HBc alone": report on a workshop. J Med Virol. 2000;62:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jilg W, Hottenträger B, Weinberger K, Schlottmann K, Frick E, Holstege A, Schölmerich J, Palitzsch KD. Prevalence of markers of hepatitis B in the adult German population. J Med Virol. 2001;63:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Knöll A, Stoehr R, Jilg W, Hartmann A. Low frequency of human polyomavirus BKV and JCV DNA in urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis and renal cell carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:487-491. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Weinberger KM, Wiedenmann E, Böhm S, Jilg W. Sensitive and accurate quantitation of hepatitis B virus DNA using a kinetic fluorescence detection system (TaqMan PCR). J Virol Methods. 2000;85:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Knöll A, Boehm S, Hahn J, Holler E, Jilg W. Reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:925-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berger A, Doerr HW, Rabenau HF, Weber B. High frequency of HCV infection in individuals with isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. Intervirology. 2000;43:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roth WK, Weber M, Petersen D, Drosten C, Buhr S, Sireis W, Weichert W, Hedges D, Seifried E. NAT for HBV and anti-HBc testing increase blood safety. Transfusion. 2002;42:869-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hennig H, Puchta I, Luhm J, Schlenke P, Goerg S, Kirchner H. Frequency and load of hepatitis B virus DNA in first-time blood donors with antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. Blood. 2002;100:2637-2641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, Chisari FV. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients' recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bréchot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-Bréchot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely "occult". Hepatology. 2001;34:194-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Paterlini P, Gerken G, Nakajima E, Terre S, D'Errico A, Grigioni W, Nalpas B, Franco D, Wands J, Kew M. Polymerase chain reaction to detect hepatitis B virus DNA and RNA sequences in primary liver cancers from patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coursaget P, Le Cann P, Leboulleux D, Diop MT, Bao O, Coll AM. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA by polymerase chain reaction in HBsAg negative Senegalese patients suffering from cirrhosis or primary liver cancer. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;67:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Cacciola I, Raffa G, Craxi A, Farinati F, Missale G, Smedile A, Tiribelli C. Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the case of occult HBV infection. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wands JR, Chura CM, Roll FJ, Maddrey WC. Serial studies of hepatitis-associated antigen and antibody in patients receiving antitumor chemotherapy for myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:105-112. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vento S, di Perri G, Luzzati R, Cruciani M, Garofano T, Mengoli C, Concia E, Bassetti D. Clinical reactivation of hepatitis B in anti-HBs-positive patients with AIDS. Lancet. 1989;1:332-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dusheiko G, Song E, Bowyer S, Whitcutt M, Maier G, Meyers A, Kew MC. Natural history of hepatitis B virus infection in renal transplant recipients--a fifteen-year follow-up. Hepatology. 1983;3:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dhédin N, Douvin C, Kuentz M, Saint Marc MF, Reman O, Rieux C, Bernaudin F, Norol F, Cordonnier C, Bobin D. Reverse seroconversion of hepatitis B after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective study of 37 patients with pretransplant anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Transplantation. 1998;66:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Czuczman MS, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Saleh M, Gordon L, LoBuglio AF, Jonas C, Klippenstein D, Dallaire B, Varns C. Treatment of patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma with the combination of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:268-276. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Joller-Jemelka HI, Wicki AN, Grob PJ. Detection of HBs antigen in "anti-HBc alone" positive sera. J Hepatol. 1994;21:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Weinberger KM, Bauer T, Böhm S, Jilg W. High genetic variability of the group-specific a-determinant of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and the corresponding fragment of the viral polymerase in chronic virus carriers lacking detectable HBsAg in serum. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1165-1174. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gaeta GB, Stornaiuolo G, Precone DF, Lobello S, Chiaramonte M, Stroffolini T, Colucci G, Rizzetto M. Epidemiological and clinical burden of chronic hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus infection. A multicenter Italian study. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1036-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Di Marco V, Lo Iacono O, Cammà C, Vaccaro A, Giunta M, Martorana G, Fuschi P, Almasio PL, Craxì A. The long-term course of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1999;30:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |