Published online Feb 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.982

Revised: April 11, 2005

Accepted: July 28, 2005

Published online: February 14, 2006

A case of a 24-year-old male with jaundice and epigastric pain is reported. The patient underwent a thorough clinical, laboratory, and imaging investigation. Computerized tomography revealed a 9 cm×10 cm choledochal cyst. Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic cholangiopancreatography were performed, during which he developed an “acute abdomen”, with radiological evidence of biliary peritoneal leak. Urgent surgery revealed rupture of the distended malformed common bile duct. A peritoneal drain was instilled and a more definitive surgical procedure was accordingly scheduled. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy following surgery verified these findings, as well as confirmed the adequacy of the urgent surgery. A combination of radiological and nuclear medicine techniques substantially contributes to the diagnosis of choledochal cyst rupture and the adequacy of surgical intervention.

- Citation: Stipsanelli E, Valsamaki P, Tsiouris S, Arka A, Papathanasiou G, Ptohis N, Lahanis S, Papantoniou V, Zerva C. Spontaneous rupture of a type IVA choledochal cyst in a young adult during radiological imaging. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(6): 982-986

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i6/982.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.982

A 24-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with jaundice and epigastric pain reflecting low in the back. The body temperature was normal. He was a heavy drinker in the previous 4 years and reported a history of infantile hyperbilirubinemia, which resolved spontaneously. He had positive Murphy and Giordano signs and a palpable epigastric mass. The laboratory examination results above normal range were as follows: WBC: 12 500/μL (neutrophil: 93.6%, lymphocyte: 5.1%), SGOT: 159 IU/L, SGPT: 559 IU/L, γGT: 520 IU/L, ALP: 244 IU/L, LDH: 699 IU/L, CPK: 606 IU/L, bilirubin (total): 7.68 mg/dL, bilirubin (direct): 6.5 mg/dL, and bile in the urine.

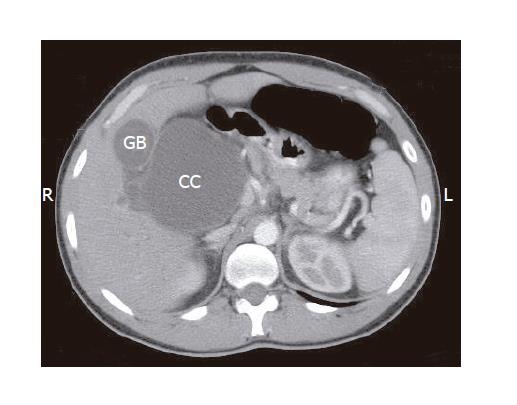

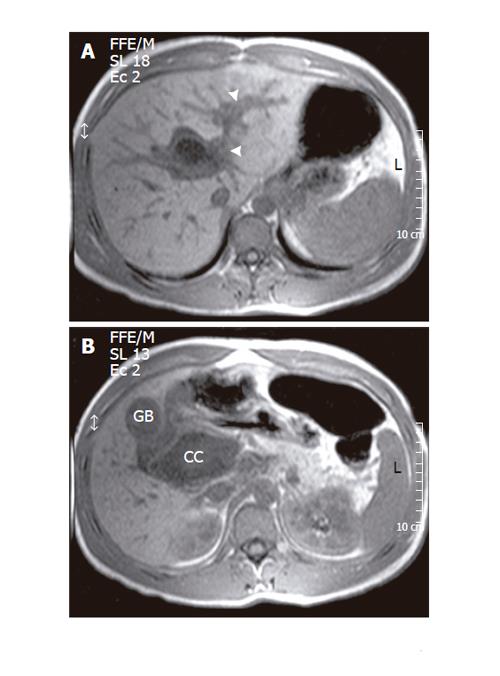

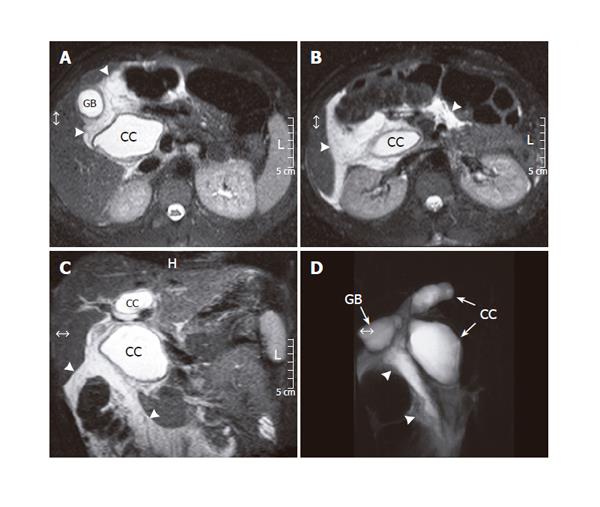

Computerized tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen was ordered, and displayed a 9 cm×10 cm cyst in the common bile duct (CBD) region, extending from porta hepatis down to the level of the third portion of the duodenum (Figure 1). Distension of intrahepatic bile ducts with stasis was also observed. The findings were consistent with a choledochal cyst (CC). Further investigation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was considered appropriate. It confirmed the intrahepatic duct distension and the large cyst (Figure 2). It was considered to be a large CC type IVA. During MRI, the patient developed “acute abdomen” symptoms. Spin echo T2-weighed images and MRCP depicted bile leak in the peritoneal cavity (Figure 3).

Immediately after MRCP he underwent urgent abdominal surgery. A 1-cm rupture of the distended CBD was found, with a considerable amount of intraperitoneal bile and focal biliary peritonitis. A Kehr tube was inserted into the CBD at the site of the rupture and the lips of the lesion were appropriately stitched.

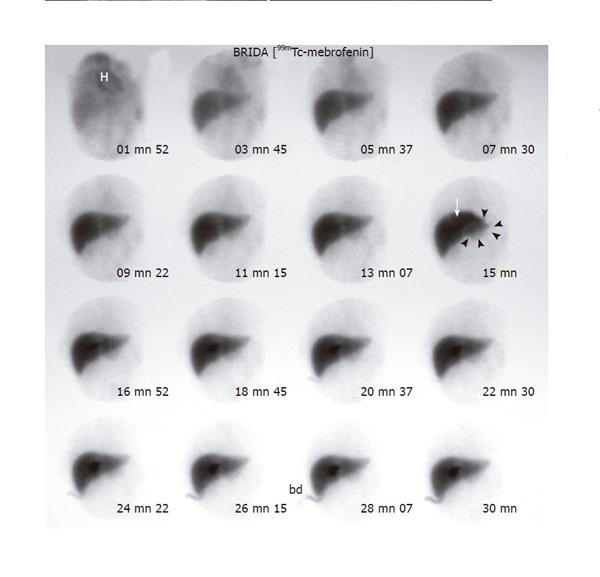

In order to verify the adequacy of the urgent surgical intervention, 99mTc-mebrofenin hepatobiliary scintigraphy was advocated on the second postoperative day. The study included a 30-min dynamic acquisition, beginning with injection and consisting of 60 30-s images (frames) of the abdomen, followed by planar static images of the upper abdomen at 1½ h and 24 h post-injection. No active leaking in the peritoneal cavity was observed throughout the study. A well-circumscribed fusiform intense tracer accumulation was observed in the right hepatic lobe near the hepatic hilum. It appeared early in the dynamic phase (Figure 4) and was most prominent in the 90-min static image while not apparent in the 24-h image (Figure 5). It corresponded to the intrahepatic moiety of the CC. A much fainter bulbous accumulation was displayed in the left hepatic lobe, extending well beyond the liver margins, and corresponded to the large extrahepatic CC moiety. It was apparent earlier in the dynamic study and still visible in the 24-h image (Figures 4 and 5).

Choledochal cysts are congenital abnormalities of the bile ducts of unknown etiology. They comprise cystic dilatations of the extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic biliary tree[1]. They are typically described as a childhood disease. Sixty percent of the patients are diagnosed during the first decade of life. Congenital cysts occur in between 1/100 000 and 1/2 000 000 live births and are more frequent in females (female-to-male ratio: 3:1 to 4:1). They are usually observed in Asian countries, especially in Japan.

Alonso-Lej et al[2] first classified CC into three major types: cystic, diverticular, and choledochocele. Todani et al[3] modified the classification system, which currently includes five types based on cholangiographic morphology and number of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct cysts (Table 1). With regard to the shape of extrahepatic and intrahepatic ducts, type IV is further classified into three subtypes: cystic-cystic, cystic-fusiform, and fusiform-fusiform. Cystic-fusiform IVA is the subtype that corresponds to our findings. In this particular subtype, intrahepatic dilatation occurs in both hepatic lobes, with the left being predominantly involved. Yet, in the present case it was the right lobe that was affected.

| Type | Characteristics | |

| IA | Dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD), with marked dilatation of part or the entire extrahepatic biliary tree and normal intrahepatic biliary tree | |

| I | IB | Focal and segmental dilatation of the distal CBD |

| IC | Fusiform dilatation of the CBD, with diffuse cylindrical dilatation of the common hepatic duct and CBD as well as normal intrahepatic biliary tree | |

| II | ||

| Diverticulum of the CBD | ||

| III | ||

| Choledochocele of the intraduodenal portion of the CBD | ||

| IVA | ||

| IV | Multiple cysts involving both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts | |

| IVB | ||

| Multiple cysts of the extrahepatic ducts only | ||

| V | ||

| Caroli’s disease | ||

Ultrasonography is the initial screening examination of choice in suspected CC. Depending on the radiologist’s skill it may reveal the type of CC. Nevertheless, inherent limitations (e.g. gas in the bowel, intra-abdominal inflammatory processes, etc.) allow for limited anatomic delineation of the non-dilated biliary system[1].

CT imaging can be relied on with a high degree of confidence in confirming an unambiguous diagnosis and providing information regarding CC relationship to the surrounding structures. It usually demonstrates a cyst, which is readily distinguished from the gallbladder as in our case. Depending on patient’s age and history, the cystic wall is thickened, especially on the ground of recurrent inflammation and cholangitis.

MRI with MRCP is the noninvasive imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of CC. The cysts appear as large fusiform or saccular dilatations producing a specific signal on T2-weighed images. Associated bile duct anomalies can also be demonstrated. On the basis of reported results, MRCP has an estimated diagnostic accuracy of 82-100%[1]. Overall, MRCP is a promising technique that may offer as much as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy is used in the setting of suspected acute cholecystitis, peritoneal biliary leak, and for the investigation of neonatal jaundice. In addition, it contributes to the diagnosis of CC, although such studies are practically acquired in a limited number of patients. Rajnish et al[4] evaluated the efficacy of hepatobiliary scintigraphy in classifying CC patients with confirmed Todani types I and IV cysts and found that it has a good accuracy in the diagnosis, correlating with ERCP or surgical findings in 86% of the cases. The false negative results are mainly attributable to its limitation in identifying small intrahepatic dilatations in type IVA. Nevertheless, in our case the fusiform tracer accumulation in the right hepatic lobe corresponds to a dilated intrahepatic duct forming a cyst and its location is uncommon (cysts are usually seen in the left lobe). This intrahepatic cyst was not a continuous extension of the extrahepatic moiety of the CC, but developed secondary to a hepatic hilum ductal stricture, a feature distinguishing CC type IVA from type I[3]. Furthermore, hepatobiliary scintigraphy can provide useful information regarding liver function, biliary patency, and biliary leak in the peritoneum.

Type IVA is observed in 30-40% of CC cases[5]. It is often accompanied with a primary ductal stenosis around the hepatic hilum, which causes either cystic or fusiform dilatation of the intrahepatic duct. The fusiform dilatation imaged in the present case mainly resulted from stricture, whereas cystic dilatation may develop due to primary stricture combined with the weakness of the intrahepatic duct epithelium. The stricture can be radiologically detected and needs cautious surgical exploration[3]. The primary management of type IVA cysts is still controversial. The intrahepatic dilatation tends to gradually reduce in size following sufficient biliary drainage. In addition, lateral hepatic segmentectomy may be necessary, especially in cases of strictures of the upper intrahepatic ducts and when the left hepatic lobe contains gallstones[6]. Patients diagnosed with type IV CC are usually adults, who commonly develop hepatolithiasis[7]. Formation of gallstones leads to the dilatation of the ducts and sometimes is complicated by intrahepatic abscess[8].

Surgical treatment should be recommended to reduce the risk of other serious complications, such as cholangitis, pancreatitis, rupture, portal hypertension, cirrhosis, and cholangiocarcinoma. Pancreatitis develops in 30-70% of adults with CC[9]. Cholangiocarcinoma may evolve in all kinds of cysts, but types I and IV are associated with a higher incidence. In these patients the prognosis is the same as in other cases of cholangiocarcinoma in the general population[10].

On rare occasions, adults may present with an acute abdomen due to CC rupture and biliary peritonitis. The reported incidence ranges between 2-18%[11]. CC perforation is generally spontaneous, although sometimes trauma may be implicated. It is more frequent in children, while in adults it is associated with conditions causing increased intra-abdominal pressure, such as pregnancy[12]. In the present case, no obvious cause of rupture was identified, considering that no kind of abdominal pressure was applied during the MRI/MRCP procedure. We thus believe that rupture was an accidental event. The recommended acute therapy for CC rupture is peritoneal drainage, followed by complete cyst resection, cholecystectomy and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction. Our patient was therefore treated primarily as a surgical emergency with peritoneal drainage and a more definitive surgical procedure was accordingly scheduled.

Controversy exists about the role of hepatic resection in types IV and V cysts due to the difficulty of intrahepatic cyst excision, thus rendering these patients to a more intense long-term follow-up. Alternatively, minimally invasive and laparoscopic treatments have been proposed[9,13,14].

In conclusion, apart from the clinical evidence, the diagnostic algorithm in this case as well as postoperative evaluation comprises information acquired by a combination of imaging modalities, namely CT, MRI/MRCP, and hepatobiliary scintigraphy. The proper handling of such patients relies upon good co-operation between several medical faculties, namely gastroenterology, radiology, nuclear medicine, and surgery, and is essential in order to prevent and treat serious complications.

The authors thank Dr. Stavroula Lyra, Mr. Alkiviadis Katsoulis, and Mr. Vasilios Makrypoulias, for their technical support.

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Kong LH

| 1. | Sawyer MAJ, Sawyer EM, Patel TH, Varma MK, Allen AW, Murphy TF; Choledochal cyst eMedicine 2004. Available from http: //www.emedicine.com/radio/topic161.htm. . |

| 2. | Alonso-lej F, Rever WB, Pessagno DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and an analysis of 94, cases. Int Abstr Surg. 1959;108:1-30. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Morotomi Y. Classification of congenital biliary cystic disease: special reference to type Ic and IVA cysts with primary ductal stricture. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rajnish A, Gambhir S, Das BK, Saxena R. Classifying choledochal cysts using hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:996-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Fujii T, Toki A, Uemura S, Koike Y. Congenital choledochal cyst with intrahepatic involvement. Arch Surg. 1984;119:1038-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lenriot JP, Gigot JF, Ségol P, Fagniez PL, Fingerhut A, Adloff M. Bile duct cysts in adults: a multi-institutional retrospective study. French Associations for Surgical Research. Ann Surg. 1998;228:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uno K, Tsuchida Y, Kawarasaki H, Ohmiya H, Honna T. Development of intrahepatic cholelithiasis long after primary excision of choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:583-588. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Martin LW, Rowe GA. Portal hypertension secondary to choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1979;190:638-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Söreide K, Körner H, Havnen J, Söreide JA. Bile duct cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1538-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee KF, Lai EC, Lai PB. Adult choledochal cyst. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maheshwari M, Parekh BR, Lahoti BK. Biliary peritonitis: a rare presentation of perforated choledochal cyst. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:588-592. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hewitt PM, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Choledochal cyst in pregnancy: a therapeutic dilemma. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:237-240. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ishibashi T, Kasahara K, Yasuda Y, Nagai H, Makino S, Kanazawa K. Malignant change in the biliary tract after excision of choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1687-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kobayashi S, Asano T, Yamasaki M, Kenmochi T, Nakagohri T, Ochiai T. Risk of bile duct carcinogenesis after excision of extrahepatic bile ducts in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Surgery. 1999;126:939-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |