INTRODUCTION

Infliximab has become the standard therapy for refractory, steroid-dependent or fistulizing Crohn’s disease[4,14,19]. The association between the use of this monoclonal chimeric mouse antibody, and increased risk of severe bacterial infections[16] and reactivation of tuberculosis[6] has received much attention. The influence of infliximab on viral infections, however, has not been extensively investigated, and data that are available on reactivation of chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B and C and EBV are conflicting. Reijasse et al[15] studied the viral kinetics of EBV in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs including infliximab and found no increased viral load in them compared to the control group. Several case studies and investigations of small patient cohorts have reported that Crohn’s disease in patients with documented pre-existing chronic hepatitis B or C was successfully treated with infliximab, without the drug causing any deterioration of the liver disease[11,13,21]. In contrast to these publications, in their prospective study of Crohn’s patients with coexisting chronic HBV-infection treated with infliximab, Esteve et al[1] observed two severe hepatitis flare-ups during treatment with this drug. Ostuni et al[12] reported on a patient with reactivated hepatitis B after therapy with infliximab and methotrexate. Michel et al[8] observed fulminant hepatic failure in a patient with inactive chronic hepatitis B after being treated with infliximab but without signs of HBV-reactivation and therefore of unknown etiology.

Several authors have recommended pre-emptive treatment with lamivudine of HBV-carriers with Crohn’s disease before starting infliximab-therapy[1,8].

FDA-recommendations released in December 2004 also alert physicians to the danger of primary hepatotoxicity or reactivation of chronic viral hepatitis caused by the administration of infliximab.

CASE REPORT

We report here on a 50-year-old patient in whom Crohn’s disease with terminal ileitis was diagnosed in January 2001. Initially he received a course of mesalamine. This, proving to be ineffective, was followed by a course of systemic steroids together with mesalamine. Steroid withdrawal was difficult, but in June 2003 steroids were discontinued and the patient was in complete remission until February 2004 when he had a relapse with abdominal pain and loose and bloody stools. Treatment was restarted with budesonide 3 mg t.i.d. and azathioprine 150 mg. Budesonide failed to improve the symptoms and steroid-therapy was switched to systemic steroids (methylprednisolone 40 mg) again. Abdominal pain and bloody stools improved under this regimen but tapering of steroids was followed by an immediate relapse despite azathioprine 2 mg/kg for several months. Endoscopy showed ulcerating inflammation in the terminal ileum and capsule endoscopy revealed involvement of the distal jejunum. Bowel surgery was discussed with the patient, but he wished to try every possible medical treatment before going for surgery. We therefore re-assessed the situation and decided to add infliximab 5 mg/kg (total amount 400 mg) because of steroid-dependent disease. Tuberculosis was excluded by tuberculin-testing and chest X-ray. Blood tests showed mild leukocytosis (14 g/L), all other results including renal and liver function tests, c-reactive protein, iron metabolism, and vitamins were within normal ranges. There was no history of any other disease before the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, besides a mild reactive depression for which the patient has been on mirtazapine for more than a year. Transaminases were documented to be within normal ranges since 2001.

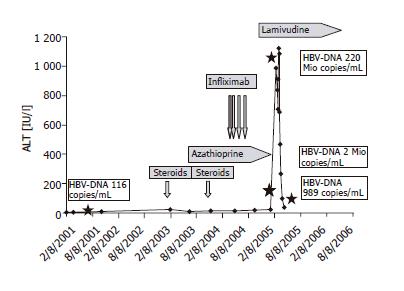

Infliximab was administered successfully at week 0, 2, and 6 followed by complete remission and rapid tapering of steroids. Basis therapy consisted at this time of azathioprine 150 mg, mirtazapine 30 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg and brotizolam 0.25 mg at night. The infusion at wk 6 was followed by 3 d of flu-like symptoms. One month after the third infliximab infusion, the patient came to the outpatient clinic because of abdominal discomfort and malaise. Blood tests showed signs of acute hepatitis (ALT 983 [normal <50 IU/L], AST 413 [normal <50 IU/L], γGT 109 [normal <66 IU/L], LDH 237 [normal <232 IU/L], bilirubin 2.17 [normal <1.28 mg/dL] and a decreased prothrombin time of 63% [normal >70%]) (course of ALT Figure 1). Liver parenchyma was hyperechogenic in sonography but there were no signs of liver cirrhosis and as expected, there were no signs of mechanical cholestasis. The patient mentioned at this point that he had been immunized against hepatitis A and B six months before by his general practitioner because all other members of his family had undergone hepatitis B and he intended to travel to Southern Europe during the summer holidays. No previous serological examination had been performed before immunization.

Figure 1 ALT remained within the normal range during therapy with prednisolone, azathioprine and during the infusions with infliximab.

Only after the fourth infusion of infliximab, the patient developed a fulminant hepatitis with ALT up to 1 100 IU/L. HBV-DNA ( ) quantification showed 220 mio copies/mL. Lamivudine (150 mg/d) was started and led to a rapid decrease in transaminases and HBV-DNA.

Complete work-up was done one week after his admission to the hospital. Hepatitis-serology revealed immunity against hepatitis A and negative serology and PCR for hepatitis C, but circulating HBs-antigen, no HBe-antigen but anti-HBe- and anti-HBc-antibodies, and negative anti-HBc-IgM were detected. Quantification of HBV-DNA showed >220 000 000 copies/mL (38 000 000 IU/mL). Other causes for hepatitis such as EBV, CMV, autoimmune hepatitis and acute Wilson's disease were ruled out. We suspected reactivation of hepatitis B from a previously unknown HBV-carrier state. This was corroborated by serology from a frozen serum sample from a previous visit in 2001 also showing the features of an HBs-antigen carrier but a low viral load with 116 copies/mL (20 IU/mL).

Antiviral therapy (lamivudine 150 mg daily) was started immediately after diagnosis. Despite the therapy, liver synthesis parameters transiently decreased and reached a nadir three weeks after the first manifestation with a prothrombin-time of 42% and bilirubin peak of 35 mg/dL. At the same time, the patient developed mild hepatic encephalopathy with increased sleepiness. One month after the diagnosis, the patient recovered, transaminases decreased and prothrombin-time normalized and HBV-DNA dropped to 2 000 000 copies/mL (340 000 IU/mL). The patient could be discharged and followed up in the outpatient clinic. The most recent visit two months after the acute hepatitis showed normal transaminases and HBV-DNA of 989 copies/mL (170 IU/mL).

DISCUSSION

While patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignancy have long been screened for chronic hepatitis B and treated prophylactically with lamivudine if positive, this has not been performed on a routine basis in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease requiring immunosuppressive regimens including infliximab. Our knowledge about the role of TNF-α in chronic viral hepatitis is sparse but there is evidence that TNF-α synergizes with interferons in suppressing viral replication[2,7,22] and is essential in clearing HBV[17]. A promoting effect for increased HBV-replication during treatment with anti-TNF-antibodies could be explained on this basis. But why HBs-antigen carriers, upon anti-TNF-α treatment, suddenly lose their tolerance against HBV and switch to a cytotoxic T-lymphocytic activation leading to hepatocyte injury and liver failure remains to be elucidated. At present we can only speculate that TNF-α might play an important role in maintaining tolerance in the HBs-antigen carrier state.

Till date there are only three case reports and one report of a small group of HBs-antigen carriers that suffered HBV-reactivation following administration of infliximab. Four patients developed fulminant hepatitis B[1,8,12] while one patient had only moderately elevated transaminases[20] that returned to normal without antiviral therapy. Esteve et al reported that two of their patients showed severe reactivation and one died from hepatic failure, but another patient on lamivudine had no worsening of liver disease during infliximab-therapy[1]. Stable HBV under lamivudine has also been reported by Oniankitan et al[11] and Valle Garcia-Sanchez et al[21]. Keeping these reports in mind and looking for other factors that might influence the course of HBV, we suggest that (1) the number of infliximab-infusions and (2) concomitant immunomodulatory therapy might influence the course of HBV-reactivation (azathioprine in our case and methotrexate therapy in the other cases with severe hepatitis).

In our patient HBV-reactivation was noted after the third infusion of infliximab. Previous treatment with steroids and azathioprine alone had not induced a flare-up in hepatitis B, although it is known that all types of immunosuppressive therapy can lead to a flare-up in hepatitis B. For steroids this has been documented most frequently in patients with hematological malignancies[18]. Azathioprine and methotrexate have also been linked with HBV-recurrence. But while this occurred on treatment with azathioprine[9], it took place only after the discontinuation of methotrexate[3,5,10].

In conclusion, our report on a patient with Crohn’s disease developing subfulminant hepatitis under infliximab treatment due to reactivation of a previously unknown HBs-antigen-carrier state draws attention to the need for screening patients with inflammatory bowel disease for hepatitis B and for antiviral prophylaxis in HBV-positive patients prior to therapy with anti-TNF-α antibodies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anna Schlögl, Gisela Egg, and Barbara Wimmer for technical and Rajam Csordas for editorial assistance.

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Kong LH