Published online Feb 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.971

Revised: June 20, 2005

Accepted: July 1, 2005

Published online: February 14, 2006

We have described a previously unreported entity of an intussuscepted neuroendocrine carcinoma of the appendix. Our patient was a 70-year-old man whose only complaint was insipient weight loss. Colonoscopy showed a malignant cecal “polyp”, and an extended right hemicolectomy was performed. We have reviewed the literature on the causes of appendiceal intussusception and their appropriate treatment options, and clarified the classification of neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Citation: Thomas RE, Maude K, Rotimi O. A case of an intussuscepted neuroendocrine carcinoma of the appendix. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(6): 971-973

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i6/971.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.971

Intussusception of the appendix is a well-recognized, though rare, entity (occurring with an incidence of 0.01% in a large autopsy series[1]). Occasionally it is accompanied by an associated appendiceal abnormality, such as an adenoma, endometriosis, carcinoid tumor or adenocarcinoma. Typically, these cases present as acute appendicitis. Less commonly, they present with chronic episodic abdominal pain, cecal mass or even rectal bleeding, for which the patient may have to undergo an endoscopic examination and the intussuscepted appendix may be interpreted as a cecal polyp. Occasionally, the patient has no gastrointestinal symptoms. Whereas carcinoid tumor (now termed as well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor) is the commonest tumor of the appendix, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the appendix is a rare entity (occurring in about 0.2% of all appendicectomy specimens[2]). We here present a case of a previously unreported phenomenon of intussusception of the appendix due to a neuroendocrine carcinoma.

A 70-year-old man presented with an 18-mo history of 13 kg weight loss. He was originally referred to the rheumatologists for investigation as he had a past medical history of rheumatoid arthritis. Other past medical history included cholecystectomy and partial gastrectomy with vagotomy for perforated duodenal ulceration. He had no gastrointestinal symptoms.

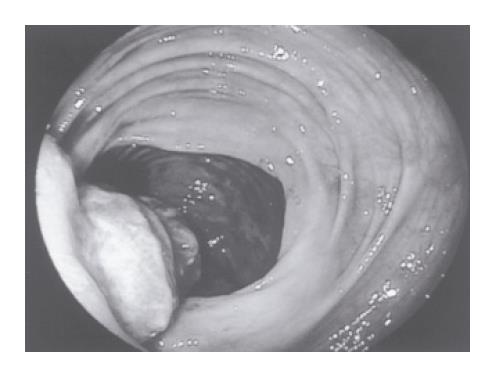

He underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with no abnormalities detected. Colonoscopy revealed a lesion in the ascending colon that appeared macroscopically malignant (Figure 1). Two further benign-looking polyps were also identified, one each in the transverse colon and at the hepatic flexure. Biopsies of the ascending colon lesion suggested adenocarcinoma. A CT scan failed to demonstrate the tumor due to extensive fecal loading. There was no evidence of metastatic disease. Pre-operative blood investigations revealed a mild iron-deficiency anemia (hemoglobin 11.9 g/dL) and no other abnormality.

During the operation, a cecal tumor was found and a large lymph node was present in the mesentery. An extended right hemicolectomy was performed and an end-to-end anastomosis fashioned.

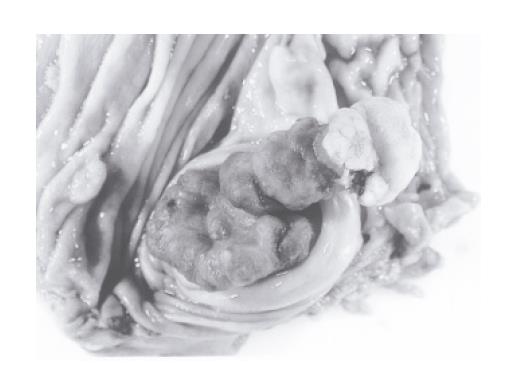

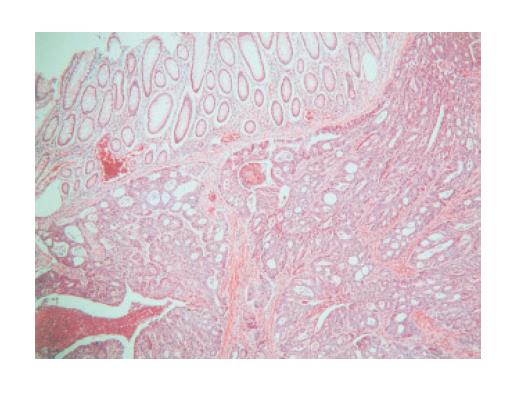

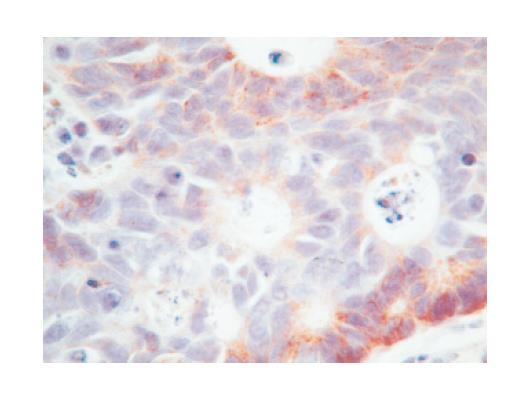

The resected specimen showed complete intussusception of the appendix, with invagination of mesoappendix fat seen at the base on the peritoneal surface. The whole of the appendix was involved by the tumor, and measured 4.5 cm in length and 2.5 cm wide at the base (Figure 2). Microscopic examination revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with a trabecular and glandular pattern (Figure 3), which was invading into the invaginated serosal fat of the appendix. Immunohistochemistry showed weak positivity with chromogranin (Figure 4) and synaptophysin, and strong membrane and cytoplasmic positivity with the low molecular weight cytokeratin (CK) marker, CAM 5.2. The tumor cells were negative for CK 20, which is usually positive in primary colorectal adenocarcinoma. The histological pattern and immunoprofile were those of neuroendocrine carcinoma. Lymphovascular invasion was identified and 1 of the 11 dissected lymph nodes contained metastatic carcinoma. The involved node was 2 cm in size and largely necrotic. Five other small polyps were also found within the specimen (2 hyperplastic, 3 adenomatous).

Post-operative recovery was uncomplicated and he was discharged 7 d post-operatively. The case was discussed at the colorectal cancer multidisciplinary (MDT) meeting and consensus was that no further adjuvant treatment was needed. He was to be followed up in the surgical clinic and was well 4 mo post-surgery.

Intussusception of the appendix is rare. In a study by Collins, of 71 000 autopsy appendiceal specimens, prevalence of intussusception was only 0.01%[1]. Clinically it is almost never diagnosed pre-operatively, most commonly mimicking acute appendicitis. It can also present with symptoms of chronic, episodic abdominal pain with or without rectal bleeding, painless rectal bleeding, or may be asymptomatic. Cases can be diagnosed preoperatively by means of radiological examination[3]. At barium enema there is an absence of appendiceal filling together with a cecal-filling defect in the anticipated location of the appendix. Ultrasound scanning may show a “target-like” picture or “concentric ring sign”, though neither of these radiological appearances is specific for an intussuscepted appendix[4]. CT scans may reveal a mass lesion within the cecum without a discernable appendix. At colonoscopy, the intussusception may be misinterpreted as a cecal polyp. Therefore, in all the cases of cecal polyp identification, the appendiceal orifice should be routinely searched for and noted to be present.

The mechanism and pathogenesis of intussusception of the appendix has been extensively studied by Fink et al[5]. It may be due to anatomical causes, such as a thin mesoappendix, a mobile appendix, or a wide appendicular lumen, or due to an associated appendiceal abnormality. These include intraluminal factors (fecoliths, foreign bodies, parasites) or intramural factors (lymphoid follicle hyperplasia, endometriosis, and tumors).

Tumors of the appendix, with or without intussusception, are uncommon. Mostly they are benign entities, such as mucocoeles, adenomata, and benign carcinoids tumors. Few are malignant, occurring in only about 1% of appendicectomy specimens[6]. In one large series, only 20% of these malignant appendiceal tumors were neuroendocrine carcinomas[2], the majority being adenocarcinomas. Using the WHO classification of endocrine tumors of the gastroenteropancreatic system (2000)[7], classical benign carcinoid tumors have been incorporated under the heading of neuroendocrine tumors, and are now termed as well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. They are considered to be of benign or uncertain malignant potential. Those with malignant features (infiltrative growth pattern, invasion into the muscularis propria, greater than 2 cm in diameter, or with nodal metastases), previously called malignant carcinoids, are now termed as neuroendocrine carcinomas, well- or poorly-differentiated. Until now, no poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the appendix have been described. Classically, well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the appendix have organoid, nesting, trabecular, rosette-like or palisading patterns, suggestive of endocrine differentiation[8]. They are associated with a worse prognosis than the more commonly diagnosed benign carcinoids/well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors.

It is important that an intussuscepted appendix is managed appropriately. In those cases uninvolved by a concurrent malignant tumor, reduction at laparotomy or laparoscopy with subsequent appendicectomy, or right hemicolectomy is the surgical treatment of choice. These lesions may be misinterpreted as a broad-based cecal polyp during colonoscopy, and subsequent endoscopic resection may result in unexpected complications, such as perforation and peritonitis[9]. Therefore, wide-stalked cecal polyps, where the appendiceal orifice cannot be visualized, should be approached with caution endoscopically. However, in the circumstances when a malignant tumor of the appendix is also present, right hemicolectomy or ileocecal resection with lymph node dissection should be performed[1]. Though a diagnosis of appendiceal intussusception had not been pre-operatively made in our patient, he underwent the correct treatment of an extended right hemicolectomy, because of the pre-operative diagnosis of a presumed malignant cecal polyp.

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Takahashi M, Sawada T, Fukuda T, Furugori T, Kuwano H. Complete appendiceal intussusception induced by primary appendiceal adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McCusker ME, Coté TR, Clegg LX, Sobin LH. Primary malignant neoplasms of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973-1998. Cancer. 2002;94:3307-3312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jevon GP, Daya D, Qizilbash AH. Intussusception of the appendix. A report of four cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:960-964. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Weissberg DL, Scheible W, Leopold GR. Ultrasonographic appearance of adult intussusception. Radiology. 1977;124:791-792. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fink VH, Santos AL, Goldberg SL. Intussusception of the appendix. Case reports and reviews of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1964;42:431-441. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Connor SJ, Hanna GB, Frizelle FA. Appendiceal tumors: retrospective clinicopathologic analysis of appendiceal tumors from 7,970 appendectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klöppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, Thaler H, Guillem J, Paty P, Cohen AM. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fazio RA, Wickremesinghe PC, Arsura EL, Rando J. Endoscopic removal of an intussuscepted appendix mimicking a polyp--an endoscopic hazard. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:556-558. [PubMed] |