Published online Nov 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7213

Revised: March 28, 2006

Accepted: April 30, 2006

Published online: November 28, 2006

A seven-month-old infant was admitted to our hospital with a 1-wk history of shortness of breath, dysphagia, and fever. Diagnosis of esophageal perforation following fish vertebra ingestion was made by history review, pneumomediastinum and an irregular hyperdense lesion noted in initial chest radiogram. Neck computed tomo-graphy (CT) confirmed that the foreign body located at the cricopharyngeal level and a small esophageal tracheal fistula was shown by esophagogram. The initial response to treatment of fish bone removal guided by panendoscopy and antibiotics administration was poor since pneumothorax plus empyema developed. Fortunately, the patient’s condition finally improved after decortication, mediastinotomy and perforated esophagus repair. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of esophageal perforation due to fish bone ingestion in infancy. In addition to particular caution that has to be taken when feeding the innocent, young victim, it may indicate the importance of surgical intervention for complicated esophageal perforation in infancy.

- Citation: Chang MY, Chang ML, Wu CT. Esophageal perforation caused by fish vertebra ingestion in a seven-month-old infant demanded surgical intervention: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(44): 7213-7215

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i44/7213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7213

In East Asia (China, Japan, Korea), fish bone ingestion is a common cause of emergency room visits and usually needs no invasive management other than prompt removal of the fish bone[1,2]. However, fish bone impaction complicated with esophageal perforation and pneumomediastinum is life-threatening and needs emergency surgical management. Most of the patients are above one year old since self-feeding has not begun at infancy. The mortality is extremely high if diagnosis is delayed and the sequelae might exhaust the patient and cause a catastrophic result. The outcome depends on the size of the rupture, the time elapsed between rupture, and diagnosis, as well as the underlying health of the patient[1]. Successful treatment is very difficult. Here, we report such a case of 7-mo-old infant of fish bone ingestion, and review the related literature.

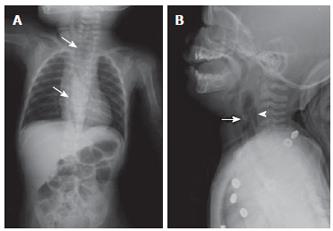

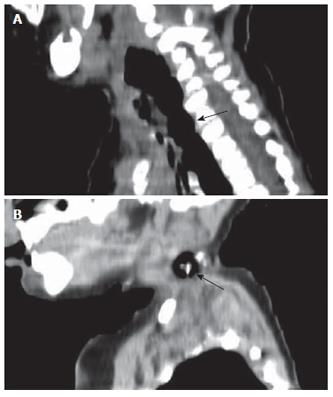

A seven-mo -old male infant weighing 7.8 kg was brought to our pediatric emergency room for progressive shortness of breath and fever over the previous 1 wk. Associated symptoms included progressive irritability, poor sleep quality, fever off and on, drooling, and dysphagia. On review of his history, he was previously healthy and had no admission record. The patient’s development and growth were within the normal range. He had been fed fish-rice soup as a nutrition supplement since the age of 5 mo. The initial chest radiogram showed pneumomediastinum (Figure 1A), and an irregular hyperdense lesion in the cricopharyngeal area was seen in the lateral view of the neck (Figure 1B). He was admitted to our pediatric Intensive Care Unit with unstable vital signs. Due to his feeding history, fish bone ingestion was strongly suspected. Emergency neck computed tomography (CT) and an esophagogram were arranged to confirm the diagnosis. The neck CT showed a hyperdense material at the cricopharyngeal level (Figure 2) and a small fistula tract at C3–C4 was noted on the esophagogram (Figure 3).

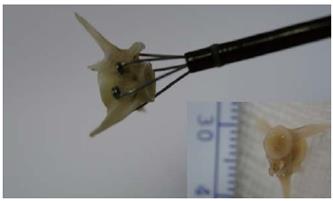

The day following admission, he was intubated via a bronchoscope to establish an accurate tube position. Panendoscopy was then performed after sufficient sedation of the patient. A fish bone (part of a vertebra) measuring 1 cm × 1 cm was found near the esophageal inlet, which was removed smoothly with grasping forceps (Figure 4).

Although the fish bone was removed, antibiotics (ceftriaxone + amikin + metronidazole) were administrated empirically to prevent esophageal wound infection. The patient continued to drool and suffer from dyspnea on the third day of admission, and a subsequent chest radiogram showed persistent retropharyngeal air collection. Bronchoscopy and panendoscopy were repeated, but did not improve the dyspnea. CT-guided retropharyngeal aspiration was performed on the fifth day of admission and 200 mL of air was aspirated. A pneumothorax with desaturation developed on the seventh day of admission, and empyema was detected after a chest tube was inserted. A pediatric surgeon was consulted, and surgery was performed. At surgery, the findings included multilocular empyema with trapped lung, mediastinitis (abscess formation), and esophageal perforation in the cervical region. Decortication and mediastinotomy were performed to remove the inflamed tissues, and the perforated esophagus was repaired with Dexon sutures. After surgical management, the medical treatment became more effective. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus was cultured in the pus, and the fever disappeared after combination treatment with antibiotics (vancomycin + ceftriaxone + metronidazole). Total parenteral nutrition was instituted, and a nasogastric (NG) tube was inserted via panendoscopy for decompression and to prevent esophageal stricture or synechia. The right Horner’s syndrome that occurred postoperatively resolved within 6 mo. Although the patient’s weight had decreased to 5.8 kg, he regained body weight steadily after beginning NG feeding (15 d after the operation). Complete oral feeding was achieved after 1 mo of NG feeding. The patient was discharged from our hospital after 4 mo, without developing the obvious symptoms of esophageal stricture. On follow-up, he weighed 7.7 kg at 8 mo (20th percentile), 9.4 kg at 13 mo (25th percentile), and 11.3 kg at 21 mo (30th percentile). No serious respiratory complications were noted.

Foreign body ingestion is common in children and can be underestimated because there are no witnesses and 50% of cases are asymptomatic[3,4]. Less than 1% of foreign body ingestions result in serious morbidity; most cases need observation only. The peak age in children is from 6 mo to 3 years[5]. Based on previous experience with the pediatric population, fish bones are the second most commonly ingested foreign body (coins are the most common). In East Asia, fish bones are the most commonly ingested foreign body[2]. Nevertheless, fish bone ingestion is quite rare in infancy since self-feeding has not begun, and the caretaker screens the food before feeding.

The symptoms of foreign body ingestion are variable and depend on the size, shape, and material of the foreign body. Usually, large sharp objects cause greater morbidity[1]. The common signs and symptoms[6] in patients with a foreign body that has been retained for less than 24 h tend to be gastrointestinal and include dysphagia, drooling, vomiting, gagging, and anorexia. Major respiratory symptoms are more common weeks or months after ingestion, such as coughing, stridor, fever, chest pain, wheezing, chronic upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, and hemoptysis. Patients may also develop acute respiratory distress with choking and cyanosis. In our case, the patient’s symptoms were compatible with typical foreign ingestion, and a lack of awareness delayed the diagnosis.

Only 32% of ingested fish bones can be identified radiographically[7], and most part of fish skeletons that cause impaction in esophagus is fish rib. Fish vertebra was seldom reported. Due to its prolonged course, pneumomediastinum was seen on the plain chest radiograph in our patient. The esophagogram confirmed the diagnosis of foreign body impaction and located the esophageal perforation. In fact, instrumental perforation and spontaneous perforation are the two major causes of esophageal injury in infants and children. Esophageal perforation due to fish bone ingestion in infancy has not been reported. Furthermore, the complications of mediastinitis, pneumothorax, and empyema were life-threatening in our patient. The following guidelines are suggested for selecting nonoperative treatment[8]: clinically stable patients; instrumental perforations detected before major mediastinal contamination has occurred, or perforations with such a long delay in diagnosis that the patient has already demonstrated tolerance for the perforation without the need for surgery; and esophageal disruptions well contained within the mediastinum or a pleural loculus. In a series of 12 children (3-7 years old) with esophageal perforation, Demirbag et al[9] reported that esophageal perforation could be treated safely by nonoperative means. Rivas et al[10] recommended conservative treatment as the best option for esophageal perforation in children. In contrast to adults, children have some important advantages in esophageal perforation with regard to complication severity, wound-healing rate, and mediastinal tissue resistance. In our case, however, the patient was younger (7 mo old), and the diagnosis delayed (about 1 wk). Although the fish bone was removed via panendoscopy soon after admission, the conservative management was ineffective, and surgery was required.

Total parenteral nutrition supplement played an important role in the postoperative therapy. It provided sufficient nutrition for the patient and allowed complete rest of the gastrointestinal tract. Treatment with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics was also essential for reversing the potentially fatal infection secondary to esophageal perforation. In this case, coagulase-negative S. aureus was identified on culturing of the pus. This organism is the predominant pathogen causing empyema in developing countries[5].

Two special techniques were applied in this case: bronchoscopy for intubation and CT-guided aspiration to reduce the retropharyngeal air collection. Both of these measures prevented deterioration in the patient’s respiratory status. The excellent outcome in this patient was beyond our expectations. No major complications were noted one year later. We believe that the great support of his family contributed equally to the medical management.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of esophageal perforation complicated by fish bone ingestion in infancy. Although current guidelines of therapy for fish bone ingestion in children remains conservative, this case illustrates the possibility of unpredictable and severe complications which demand surgical intervention.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Lai AT, Chow TL, Lee DT, Kwok SP. Risk factors predicting the development of complications after foreign body ingestion. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1531-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arana A, Hauser B, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Vandenplas Y. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Uyemura MC. Foreign body ingestion in children. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:287-291. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Jaffé A, Balfour-Lynn IM. Management of empyema in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dahshan A. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2001;94:183-186. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wai Pak M, Chung Lee W, Kwok Fung H, van Hasselt CA. A prospective study of foreign-body ingestion in 311 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58:37-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ngan JH, Fok PJ, Lai EC, Branicki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion. Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211:459-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaffer HA Jr, Valenzuela G, Mittal RK. Esophageal perforation. A reassessment of the criteria for choosing medical or surgical therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:757-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Demirbag S, Tiryaki T, Atabek C, Surer I, Ozturk H, Cetinkursun S. Conservative approach to the mediastinitis in childhood secondary to esophageal perforation. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2005;44:131-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rivas S, Martínez L, Hernández F, Avila LF, Lassaletta L, Murcia J, Olivares P, Fernández A, Queizán A, López Santamaría M. [Aggressive conservative treatment remains the best option for oesophageal perforation in children]. Cir Pediatr. 2004;17:3-7. [PubMed] |