Published online Nov 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6879

Revised: September 23, 2006

Accepted: September 28, 2006

Published online: November 14, 2006

AIM: To determine the prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) -positive patients at a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India.

METHODS: Serum samples from 451 HIV positive patients were analyzed for HBsAg and HCV antibodies during three years (Jan 2003-Dec 2005). The control group comprised of apparently healthy bone-marrow and renal donors.

RESULTS: The study population comprised essentially of heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. The prevalence rate of HBsAg in this population was 5.3% as compared to 1.4% in apparently healthy donors (P < 0.001). Though prevalence of HCV co-infection (2.43%) was lower than HBV in this group of HIV positive patients, the prevalence was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than controls (0.7%). Triple infection of HIV, HBV and HCV was not detected in any patient.

CONCLUSION: Our study shows a significantly high prevalence of hepatitis virus infections in HIV infected patients. Hepatitis viruses in HIV may lead to faster progression to liver cirrhosis and a higher risk of antiretroviral therapy induced hepatotoxicity. Therefore, it would be advisable to detect hepatitis virus co-infections in these patients at the earliest.

- Citation: Gupta S, Singh S. Hepatitis B and C virus co-infections in human immunodeficiency virus positive North Indian patients. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(42): 6879-6883

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i42/6879.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6879

Diseases of the hepatobiliary system are a major problem in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. An estimated one-third of deaths in HIV patients are directly or indirectly related to liver disease. Liver diseases in HIV infected persons can occur due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infections, chronic alcoholism, hepatic tuberculosis, or due to the effects of anti-retroviral therapy (ART)[1,2]. Since the principal routes for HIV transmission are similar to that followed by the hepatotropic viruses, as a consequence, infections with HBV and HCV are expected in HIV infected patients. Co-infections of HBV and HCV with HIV have been associated with reduced survival, increased risk of progression to liver disease and increased risk of hepatotoxicity associated with anti-retroviral therapy.

Worldwide, HIV is responsible for 38.6 million infections as estimated at the end of 2005[3] while HBV and HCV account for around 370 million and 130 million chronic infections respectively. Moreover, among the HIV-infected patients, 2-4 million are estimated to have chronic HBV co-infection while 4-5 million are co-infected with HCV[4]. The reported co-infection rates of HBV and HCV in HIV patients have been variable worldwide depending on the geographic regions, risk groups and the type of exposure involved[4-8]. In Europe and USA, HIV-HBV co-infection has been seen in 6%-14%[4,5] of all patients while HIV-HCV co-infection has been variably reported ranging from 25% to almost 50%[6,7] of these patients. Evidence of exposure to HBV and HCV has been found in 8.7% and 7.8%, respectively, of HIV patients from Thailand[8] in Southeast Asia.

India, with a whopping 5.2 million cases of HIV infection, has distinction of harboring the second highest number of these patients in the world. Within India also, variable co-infection rates have been reported from region to region. HIV-HBV co-infection (HBsAg positives) is reported in 6% of people from Chennai, South India[9], 7.5% in Chandigarh, Northwest India[10] and 16% in Mumbai, Western India[2]. Similarly, HIV-HCV co-infection rates also vary from 4.8%-21.4% in South India[9,11] and 30% in Western India[2] to as high as 92% in the North-East[12].

While HIV-HBV co-infection has been linked to both sexual and intravenous injection route of transmission, the HIV-HCV co-infection has predominantly been associated with non-sexual parenteral route of transmission. In India, HIV infection is predominantly acquired through heterosexual route, but no work from India has been carried out to study the differential transmission rate of these two hepatitis viruses in HIV positive persons. With this background we set out to determine the prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in HIV-positive patients coming to a tertiary care hospital located in north India.

The study was carried out in the Microbiology Division, Department of Laboratory Medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). Patients attending clinics at AIIMS were screened for HIV based on clinical suspicion after pre-test counseling and informed consent. As a routine, our laboratory follows the World Health Organization (WHO) testing strategies for HIV testing. Only the confirmed HIV positive serum samples were included in this study and were anonymously tested for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV antibodies. The study period was from January 2003 to December 2005. Seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV antibodies in apparently healthy, HIV-negative organ-donors (kidney/bone-marrow) was also analyzed during the same study period and compared with the prevalence of hepatitis markers in HIV positive individuals. These organ donors are screened for viral markers as a routine work-up for their family members requiring organ transplant.

The serum samples which were found to be HIV positive according to WHO testing strategy III were coded and stored at -20 degree Celsius. The coded samples were anonymously tested using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kits at a later date for the presence of HBsAg (Cat. No.B9 280252, bio Merieux, France) and anti-HCV antibodies (DETECT-HCVTM Third generation, Cat. No. HCA 702B/700B, Adaltis, Italy). All serum samples were tested in duplicate.

Comparison of proportions between HIV-infected and non-infected individuals was done using Chi-square tests. P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Sera from a total of 451 HIV-positive patients were included in this study. The retrospective demographic data of these subjects showed that out of the 451 patients, 345 (76.4%) were males and 106 (23.6%) females. The mean age of the study group was 32 years (95% CI +/- 3.2 years, range 5-70 years). The predominant mode of acquiring HIV infection was heterosexual contact (80%) followed by transfusion of blood products (6%), intravenous drug use (2.3%) and the rest unknown.

Data was available for 428 prospective organ donors who were also tested during the same period. It was presumed that these donors represent the general population and they are exposed to similar risk factors as the general population. There were 259 (60.5%) males and 169 (39.5%) females. The mean age of the donors was 38.4 years (95% CI +/- 1.1 years, range 16-67 years).

Overall, the prevalence of co-infection in HIV-positive patients with hepatitis viruses was 7.76% (35 in 451). Among the co-infected patients, there were 29 males and 6 females. Triple infection with both HBsAg and HCV was not seen in any HIV patient.

The rate of HBsAg co-infection was 5.32% (24 in 451) in HIV positive patients as compared to HBsAg prevalence of 1.4% in apparently healthy donors (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Among males, HIV/HBV co-infection was seen in 23 of 345 (6.6%) patients while HBsAg was positive in only 4 out of 259 male donors (1.5%). Among the females, HIV/HBV co-infection was seen in only 1 of 106 (0.94%) patients while 2 out of 169 (1.1%) female donors were HBsAg positive. HBsAg co-infection rates were significantly higher in HIV positive men than in women (P < 0.025). HBsAg prevalence was also significantly higher in HIV males as compared to control males (P < 0.01), but such significance was not seen in females.

The rate of HCV co-infection was 2.43% (11 in 451) in HIV positive patients as compared to 0.70% in controls (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Among males, HIV/HCV co-infection was seen in 6 of 345 (1.7%) patients while only 2 out of 259 (0.7%) male donors were HCV positive. Among females, HIV/HCV co-infection was found in 5 of 106 (4.7%) patients while only 1 of 169 (0.59%) female donors was HCV positive. No statistically significant difference was seen in HCV co-infection rates between HIV positive men and women. But, the HCV seroprevalence was significantly higher in HIV positive female patients as compared to female donors (P < 0.05).

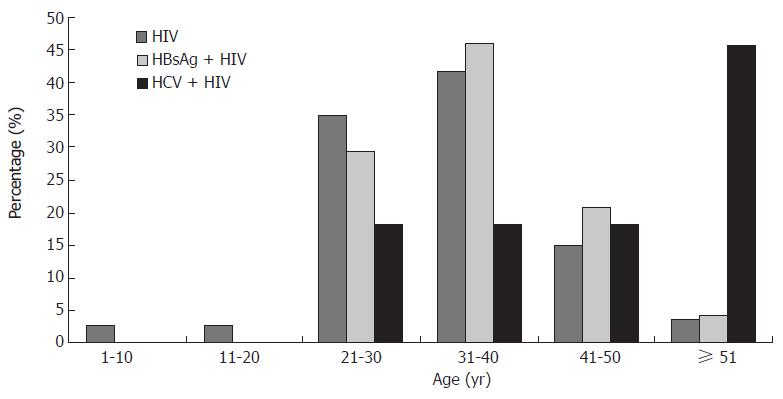

The majority of the HIV-infected patients comprised the 31-40 years age group (41.5%) followed by the 21-30 year age group (34.7%). Mean age of the HIV positive patients was 32 years (95% CI +/- 3.2 years) while that of the co-infected patients was 37.7 years (95% CI +/- 3.2 years). HBV-HIV co-infection was seen highest in the 31-40 year age group (45.8%) while HCV-HIV co-infection was predominant in the ≥ 51 years of age (45.4%) (Figure 1).

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that 38.6 million people were living with HIV globally at the end of 2005[3]. India alone had the second highest number of people living with HIV (5.2 million) by the end of 2005[13]. Globally, around three million people died of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) related illnesses in 2005[3]. About two-thirds of patients with AIDS develop hepatomegaly and abnormalities in serum biochemical parameters of liver function[14]. Liver damage may be directly related to HIV infection or may result from conditions such as alcoholism, prior viral hepatitis or intravenous drug abuse, which are highly prevalent in patients with HIV infection[2]. In addition, sepsis, malnutrition, or the administration of possibly hepatotoxic antiretroviral medications may also lead to liver damage[15,16].

Due to declining opportunistic infections as a result of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), life expectancy of patients with HIV has increased. As a consequence, focus has shifted to the management of concurrent illnesses such as chronic HBV and HCV infections which have the potential to increase long term morbidity and mortality. As a result of the shared epidemiological factors, patients infected with HIV have a higher risk of both HBV and HCV infection as compared to those uninfected with HIV. It is very likely that the presence of HIV infection makes the transmission of hepatitis viruses more efficient, both through sexual contact as well as perinatal contact[17]. This has also been directly correlated with the degree of immunosuppression and viral load. Though HCV transmission is not widely documented through sexual contact but the presence of HIV may facilitate transmission of HCV in HIV positive individuals who otherwise have no history of blood transfusion or injection drug abuse.

Our study findings indicate that HIV-infected men and women are at a high-risk of viral co-infections, as illustrated by the high prevalence of HBsAg (5.32%) and HCV (2.43%) antibodies (Table 1). This study showed that infection with these viruses in the test group was significantly higher than the comparable group of healthy adult organ donors at the same hospital. The study group predominantly comprised of heterosexually acquired HIV infections. Also, a significant risk for HBV was seen in males. This is similar to previous reports that male gender is associated with a significant higher risk of co-infections with HBV[4]. The carriage of HBsAg in our study matches with that of Kumarasamy et al[9] from South India and at the National AIDS Research Institute, and of Pune (4.8%)[18] from Western India.

HCV prevalence in our study group was lower than other studies from Western countries and other parts of India. This can be related to the type of risk-groups in this study. Saha et al[11] reported an HCV co-infection rate of 92% in intravenous drug-users from Northeast India, while in the report by Kumarasamy et al[9] HCV co-infection was seen at 4.8%, but in those patients 25% had a history of blood transfusion and 50% were injection drug users (IVDU). However, in our study group IVDUs comprised only 2% of the patients while the majority of HIV infections were heterosexually transmitted. The low HCV prevalence in our data could be attributed to the mode of transmission of these viruses. While epidemiological evidence indicates sexual transmission of HCV, this occurs much less efficiently than HBV or HIV. Moreover, we need to address other possible non-sexual sources of HCV acquisition which are often overlooked[19] and several methodological shortcomings that tend to overestimate the proportion of HCV infections attributed to sexual contact. Earlier studies used first-generation antibodies for HCV assays which have a higher false positive rate than presently available third-generation assays. Moreover, only limited studies performed virological analyses to confirm that anti-HCV concordant sexual partners were infected with the same virus. In addition, other independent non-sexual factors need to be looked for such as prior history of injection drug use, tattooing, or sharing of razors and toothbrushes.

HCV-HIV co-infection in our male patients was higher than HCV mono-infection in male donors, though not statistically significant. Among HIV positives, though females showed a higher HCV co-infection rate as compared to males, the patient numbers were not comparable. Among the female group, HIV/HCV co-infection was significantly higher than HCV mono-infection in donors (P < 0.05). HIV co-infection appears to increase the rate of HCV transmission by sexual contact. In India, the majority of the women are in a monogamous relationship with their husbands and usually acquire HIV infection from their spouse. Therefore, while the risk for HCV acquisition in steady monogamous relationships is quite low[19], we need to look into other factors like sharing of toothbrushes and other contaminated personal items with her husband who may be the index for the HCV infection.

At present, limited clinical information is available about the possible effects of HBV and HCV co-infection and the reciprocal interactions between these hepatotropic viruses and HIV. In the post-HAART era, with increased survival of HIV infected patients, HCV-induced liver disease has emerged as a leading cause of significant morbidity and death in this population[6,7]. Clinically, hepatitis C is a more severe disease in HIV-infected individuals rather than HCV mono-infection alone. HIV/HCV co-infected patients have a faster rate of HCV-related liver fibrosis and a more rapid progression to liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma than HCV mono-infected persons[20-22]. In contrast, most studies have shown that HCV does not influence progression of HIV infection to AIDS or death[20].

There is also evidence that HIV may modify the natural history of HBV infection[23,24]. HIV positive subjects have higher rates of HBV chronic carriage, higher HBV replication and lower rates of seroconversion to anti-HBe and anti-HBs antibodies. The impact of HIV co-infection on the outcome of HBV infection is still controversial; while some studies have shown a rapid progression of liver fibrosis and an accelerated progression towards decompensated cirrhosis in HIV co-infected subjects[24], others have shown decreased liver necro-inflammatory processes[25]. Though some studies from the pre-HAART era described a more rapid progression to AIDS in patients having chronic HBV infection[26], post-HAART, no impact of HBV co-infection on HIV-disease progression has been detected[27].

Presently, ongoing clinical trials with pegylated interferon and ribavirin are reported to show encouraging results in HIV/HCV co-infected patients[7] while lamivudine and other combinations are also encouraging in HIV/HBV co-infections[28]. Therefore, with newer drug formulations it is now becoming evident that early initiation of therapy before marked immunosuppression sets in could be highly beneficial for the HIV infected patient, in order to decrease long term mortality and morbidity associated with these co-infections.

Co-infection of HIV with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses is seen in 5.3% and 2.4% patients, respectively. This is significantly higher as compared to the prevalence of these two hepatitis virus infections in control population of the representative region of the country. Therefore, universal screening for hepatitis B and C viral infections in all HIV positive patients should urgently be started in Asia also.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Kumarasamy N, Vallabhaneni S, Flanigan TP, Mayer KH, Solomon S. Clinical profile of HIV in India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:377-394. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rathi PM, Amarapurkar DN, Borges NE, Koppikar GV, Kalro RH. Spectrum of liver diseases in HIV infection. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1997;16:94-95. [PubMed] |

| 3. | 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp. Accessed on 2.6.2006. |

| 4. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S6-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 637] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rockstroh JK. Management of hepatitis B and C in HIV co-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34 Suppl 1:S59-S65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dodig M, Tavill AS. Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus coinfections. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tien PC. Management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected adults: recommendations from the Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and National Hepatitis C Program Office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2338-2354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sungkanuparph S, Vibhagool A, Manosuthi W, Kiertiburanakul S, Atamasirikul K, Aumkhyan A, Thakkinstian A. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus in Thai patients: a tertiary-care-based study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:1349-1354. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Flanigan TP, Hemalatha R, Thyagarajan SP, Mayer KH. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus disease in southern India. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sud A, Singh J, Dhiman RK, Wanchu A, Singh S, Chawla Y. Hepatitis B virus co-infection in HIV infected patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2001;22:90-92. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Bhattacharya S, Badrinath S, Hamide A, Sujatha S. Co-infection with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus among patients with sexually transmitted diseases in Pondicherry, South India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:495-497. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Saha MK, Chakrabarti S, Panda S, Naik TN, Manna B, Chatterjee A, Detels R, Bhattacharya SK. Prevalence of HCV & HBV infection amongst HIV seropositive intravenous drug users & their non-injecting wives in Manipur, India. Indian J Med Res. 2000;111:37-39. [PubMed] |

| 13. | National AIDS Control Organization (NACO). HIV/AIDS epidemiological Surveillance & Estimation report for the year 2005. Available from: http://www.nacoonline.org/. Accessed on 2.6.2006. |

| 14. | Chalasani N, Wilcox CM. Etiology, evaluation, and outcome of jaundice in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Hepatology. 1996;23:728-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schneiderman DJ, Arenson DM, Cello JP, Margaretten W, Weber TE. Hepatic disease in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Hepatology. 1987;7:925-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Poles MA, Dieterich DT, Schwarz ED, Weinshel EH, Lew EA, Lew R, Scholes JV. Liver biopsy findings in 501 patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:170-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Eyster ME, Alter HJ, Aledort LM, Quan S, Hatzakis A, Goedert JJ. Heterosexual co-transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | National AIDS Research Institute Annual Report 2003-04. Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/annual/nari/2003-04/annual_report.htm. Accessed on 24.5.2006. |

| 19. | Terrault NA. Sexual activity as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bräu N. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients in the era of pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:33-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wright TL, Hollander H, Pu X, Held MJ, Lipson P, Quan S, Polito A, Thaler MM, Bacchetti P, Scharschmidt BF. Hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients with and without AIDS: prevalence and relationship to patient survival. Hepatology. 1994;20:1152-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vallet-Pichard A, Pol S. Natural history and predictors of severity of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S28-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Puoti M, Airoldi M, Bruno R, Zanini B, Spinetti A, Pezzoli C, Patroni A, Castelli F, Sacchi P, Filice G. Hepatitis B virus co-infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. AIDS Rev. 2002;4:27-35. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Puoti M, Torti C, Bruno R, Filice G, Carosi G. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B in co-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S65-S70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Herrero Martínez E. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C co-infection in patients with HIV. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:253-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Scharschmidt BF, Held MJ, Hollander HH, Read AE, Lavine JE, Veereman G, McGuire RF, Thaler MM. Hepatitis B in patients with HIV infection: relationship to AIDS and patient survival. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:837-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rockstroh JK. Influence of viral hepatitis on HIV infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S25-S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Soriano V, Puoti M, Bonacini M, Brook G, Cargnel A, Rockstroh J, Thio C, Benhamou Y. Care of patients with chronic hepatitis B and HIV co-infection: recommendations from an HIV-HBV International Panel. AIDS. 2005;19:221-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |