Published online Nov 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6850

Revised: July 1, 2006

Accepted: July 7, 2006

Published online: November 14, 2006

AIM: To characterize functional biliary pain and other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS) patients with and without sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) proved by endoscopic sphincter of Oddi manometry (ESOM), and to assess the post-endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) outcome.

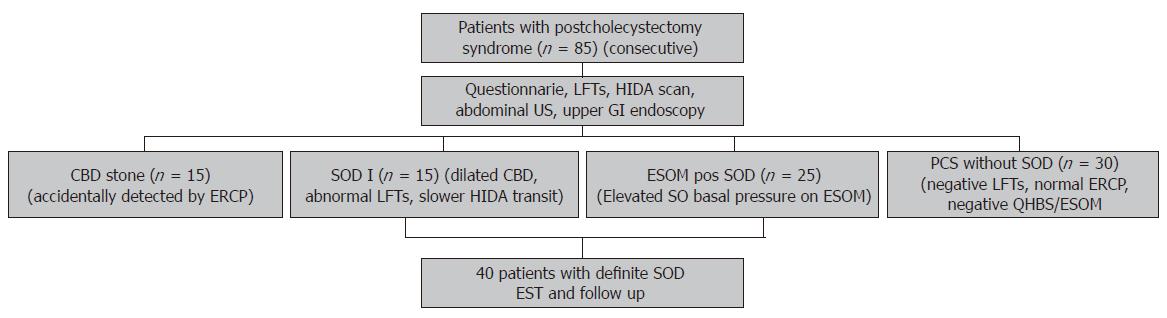

METHODS: We prospectively investigated 85 cholecystectomized patients referred for ERCP because of PCS and suspected SOD. On admission, all patients completed our questionnaire. Physical examination, laboratory tests, abdominal ultrasound, quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (QHBS), and ERCP were performed in all patients. Based on clinical and ERCP findings 15 patients had unexpected bile duct stone disease and 15 patients had SOD biliary typeI. ESOM demonstrated an elevated basal pressure in 25 patients with SOD biliary-type III. In the remaining 30 cholecystectomized patients without SOD, the liver function tests, ERCP, QHBS and ESOM were all normal. As a control group, 30 ‘asymptomatic’ cholecystectomized volunteers (attended to our hospital for general cardiovascular screening) completed our questionnaire, which is consisted of 50 separate questions on GI symptoms and abdominal pain characteristics. Severity of the abdominal pain (frequency and intensity) was assessed with a visual analogue scale (VAS). In 40 of 80 patients having definite SOD (i.e. patients with SOD biliary typeIand those with elevated SO basal pressure on ESOM), an EST was performed just after ERCP. In these patients repeated questionnaires were filled at each follow-up visit (at 3 and 6 mo) and a second look QHBS was performed 3 mo after the EST to assess the functional response to EST.

RESULTS: The analysis of characteristics of the abdominal pain demonstrated that patients with common bile duct stone and definite SOD had a significantly higher score of symptomatic agreement with previously determined biliary-like pain features than patient groups of PCS without SOD and controls. In contrary, no significant differences were found when the pain severity scores were compared in different groups of PCS patients. In patients with definite SOD, EST induced a significant acceleration of the transpapillary bile flow; and based on the comparison of VASs obtained from the pre- and post-EST questionnaires, the severity scores of abdominal pain were significantly improved, however, only 15 of 35 (43%) patients became completely pain free. Post-EST severity of abdominal pain by VASs was significantly higher in patients with predominant dyspepsia at initial presentation as compared to those without dyspeptic symptoms.

CONCLUSION: Persistent GI symptoms and general patient dissatisfaction is a rather common finding after EST in patients with SOD, and correlated with the presence of predominant dyspeptic symptoms at the initial presentation, but does not depend on the technical and functional success of EST.

- Citation: Madácsy L, Fejes R, Kurucsai G, Joó I, Székely A, Bertalan V, Szepes A, Lonovics J. Characterization of functional biliary pain and dyspeptic symptoms in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: Effect of papillotomy. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(42): 6850-6856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i42/6850.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6850

Sphincter of Oddi (SO) dysfunction is thought to responsible for postcholecystectomy abdominal pain in up to 13% of patients[1]. Endoscopic sphincter of Oddi manometry (ESOM) is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD)[2], and in patients with definite SOD (patients with elevated SO basal pressure and those with SOD biliary typeI, i.e. clinical signs of biliary obstruction due to SO stenosis), endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is regarded as the most definitive treatment. Initially, several controlled landmark studies have supported this therapeutical approach[3-5]; however in the majority of these studies the primary end point was the general symptomatic improvement after EST, and no detailed analysis of the global spectrum of the GI symptoms has been performed. Moreover, as we learned from a recent cohort study, although up to 69% of the postcholecystectomy patients with definite SOD exhibited an overall symptomatic relief after EST as compared with only 31% relief in the sham control group, only 18% of the responder patients became completely asymptomatic after EST[6]. In other words, regardless of optimal diagnostic approach and therapy in patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS), a significant proportion of these patients will never be completely asymptomatic. One explanation might be that similar to those patients with poor outcome after cholecystectomy, the presence of dyspepsia and other GI symptoms before papillotomy may be continued after EST, and this might influence the overall outcome and patient satisfaction[7]. Another critical point could be that ESOM alone is an insufficient method for optimal patient selection for EST, and this might worsen the effectiveness. Therefore, the aims of the present prospective study were to precisely characterize functional biliary pain and other GI symptoms in patients having PCS with and without SO motility disorders documented by ESOM and/or quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (QHBS), and to assess the post-EST outcome of these symptoms.

During the period of year 2001-2005, we prospectively investigated 85 consecutive cholecystectomized patients referred to our endoscopy unit for ERCP because of suspected SOD (Figure 1). On admission, all patients completed our standardized and validated questionnaire on pain and GI symptoms. Liver function tests (LFTs) [ALAT, ASAT, alkaline phosphatase (AP), γGT, serum bilirubin], abdominal ultrasonography, upper GI endoscopy with antral biopsy to test H pylori, quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (QHBS), ERCP and in the presence of clear indication ESOM were performed in each patient with suspected SOD. Based on clinical data and ERCP results our patients were categorised by the Geenen and Hogan classification as follows: SOD biliary group typeI, II and III. In order to prevent repeated ERCPs and reduce the post-procedure complication rate, we studied the presence of delayed transpapillary bile flow (longer than 45 min) by QHBS instead of measuring the ERCP contrast drainage time. In 15 of 85 patients an unexpected common bile duct (CBD) stone was detected on the ERCP, and therefore an EST and a stone extraction were completed immediately (CBD stone group). According to the elevated LFTs, abnormal QHBS and dilated bile duct on ERCP, 15 of 85 patients were categorised as SOD biliary type I (SOD I group). In these SOD typeIpatients, an EST was performed just after the ERCP without ESOM. An EST was also performed in a further 25 patients with SOD biliary type II or III, accompanied with an elevated SO basal pressure (over 40 mm Hg) demonstrated on ESOM (ESOM positive SOD group). Finally, in 30 of 85 patients a PCS without SOD was diagnosed (all of them belonged to SOD biliary type II and III), based on normal LFTs, normal ERCP and negative QHBS and/or ESOM (SOD negative PCS group) (Figure 1). As a control group, 30 ‘asymptomatic’ cholecystectomized volunteers (attended to our hospital for general cardiovascular screening and none of them had been investigated earlier for postcholecystectomy symptoms) were also included in our study, and they filled our questionnaire repeatedly (cholecystectomized control group). In the control group, no further investigation was performed to diagnose functional biliary diseases for lack of indication.

In 40 of 80 patients having definite SOD (i.e., patients with SOD biliary typeIand those with elevated SO basal pressure on ESOM) an EST was performed just after ERCP (Figure 1). The frequency of mild post-procedure pancreatitis was 14.8%, but no severe complication or procedure related death occurred. Thirty-five of these 40 patients were followed-up for up to 12 mo after the procedure. In these 35 patients repeated questionnaires were filled at each check-up (every 3-6 mo) and a second look QHBS was performed at the 3rd month after the procedure to assess the beneficial effect of EST. Unfortunately 5 patients were dropped out from this arm of the study, which was always due to poor patient co-operation.

Before entering the study all patients were informed about the study, and all gave written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Szeged and was in accordance with the Helsinki II Declaration.

Our questionnaire consisted of 50 separate questions on personal data, symptom characteristics and severity of abdominal pain assessed with a visual analogue scale (VAS). The patients were asked to rate their pain frequency and intensity on two separate 100 mm scale with the margins of “no pain at all” on the left and “continuous pain” on the right, vs “no pain at all” on the left and “worst possible pain” on the right, respectively. Patients were requested to mark on the VAS how frequent and intensive of their abdominal pain. Severity scores of abdominal pain were calculated by simple addition of VASs of frequency and intensity. Symptomatic characteristics of abdominal pain were assessed further by six questions (four possible answers each), in which the localization, duration, type, connection with feeding, aggravating and relieving factors were precisely determined. According to the literature, biliary-type pains were initially defined as typically localized in the epigastrium or the right upper quadrant, with episodes of steady pain that lasts more than 15-30 min, maybe aggravated by food or fatty food and relieved after spasmolytics or due to low-fat diet. Other possible answers in this part of our questionnaire were focused to characterize possible symptoms of non-biliary diseases such as acid related disorders, dysmotility type dyspepsia, and radiating pain stemming from the thoracic or lumbar zygapophysial joints, i.e. facet syndrome. These abdominal pain characteristics were then scored by counting the cumulative number of the affirmative patient answers that precisely matched with previously described definitions of biliary-type pain.

There were further 28 questions on dyspeptic symptoms, and each of them was assessed by VAS of frequency and intensity in a similar manner as described above. In this part the patients were asked whether they were bothered by heartburn, acid regurgitation, early satiety, bloating and abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, vomiting of bile, flatulence, borborygmus, diarrhea, constipation, intermittent constipation and diarrhea, anorexia and weight loss. The duration of symptoms and the relation to time of previous cholecystectomy were also determined. The next section aimed to detect psychological vulnerability and neurotic symptoms and consisted of separate questions on psychosomatic and neurotic symptoms, with yes/no category answers. Psychological vulnerability was also scored by counting the cumulative number of affirmative answers. Some previous points of medical history, such as pancreatitis and alcohol consumption were also noted.

For statistical evaluation the Kruskal-Wallis followed by the Mann-Whitney U tests (quantitative variables) or the chi-square tests (qualitative variables) were applied. Significance was achieved at P < 0.05. All results are given as mean, standard error and standard deviation.

QHBS was performed with our standard technique as it was published and validated earlier[8] and was strictly performed in a few days before any invasive procedure. Time-to-peak (Tmax) and half-time-excretion (Thalf) parameters were calculated over the liver parenchyma (L), hepatic hilum (H) and common bile duct (C). The duodenal appearance time (DAT) was also measured. ESOM was performed with the application of the standard station pull through manometric technique[8]. ESOM recording was considered abnormal in cases demonstrating an elevated SO basal pressure (over 40 mm Hg, lasting more than 30 s).

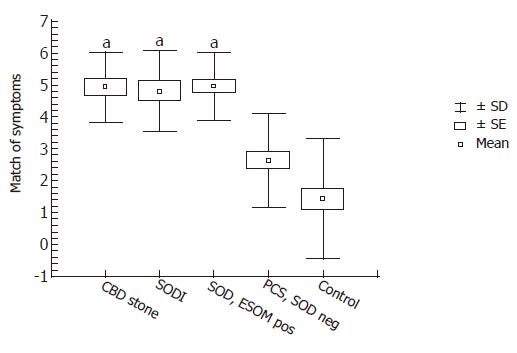

Analysis of the characteristics of abdominal pain demonstrated, that in patients with CBD stone, SOD I and ESOM positive SOD there was significantly higher score of symptomatic agreement with the previously determined biliary-type pain features than in patient groups with SOD negative PCS and controls (Figure 2). Interestingly, patients with definite SOD (i.e., SOD I and ESOM positive SOD) had exactly similar biliary pain characteristics compared with patients with CBD stone disease. However, most of our patients with SOD negative PCS had atypical pain and symptom presentation.

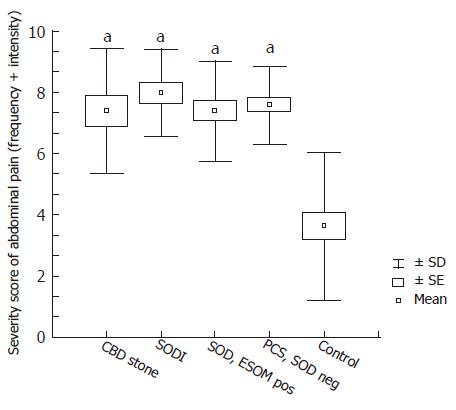

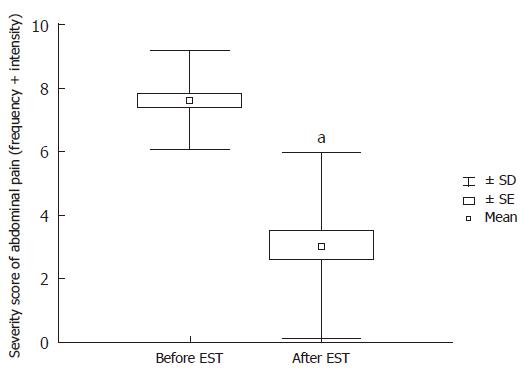

When the severity scores of abdominal pain at presentation were analysed, all patient groups (CBD stone, SOD I, ESOM positive SOD, and SOD negative PCS) had significantly higher pain severity than the cholecystectomized controls (Figure 3). In fact, the severity level of abdominal pain in SOD negative PCS patients was similar to that in patients having organic disorder such as CBD stone or SODI. Therefore, in contrast to symptomatic characteristics, the severity of abdominal pain had no diagnostic value in differentiating patients with and without SOD.

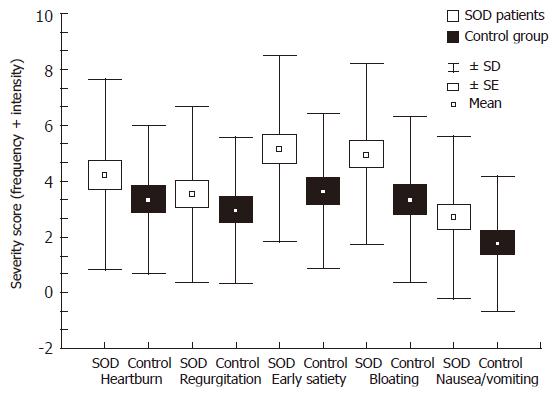

Based on the analysis of our questionnaire, in 40 patients with definite SOD (SODIpatients and ESOM positive patients) a higher prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms associated with biliary-pain was found as compared to controls (Figure 4). The most prevalent dyspeptic symptom was early satiety and bloating, followed by heartburn, regurgitation and nausea or vomiting. Although there was an obvious tendency of higher dyspeptic scores in definite SOD patients, none of the separate symptom scores reached the level of significance as compared to cholecystectomized controls. The prevalence of antral gastritis and Helicobacter infection was similar in patients with definite SOD versus in patients with SOD negative PCS: 77% and 27% vs 87% and 25%, respectively. No statistical difference was detected between these groups, indicating that dyspeptic symptoms had no relation to antral predominant gastritis or H pylori infection in these cholecystectomized patients.

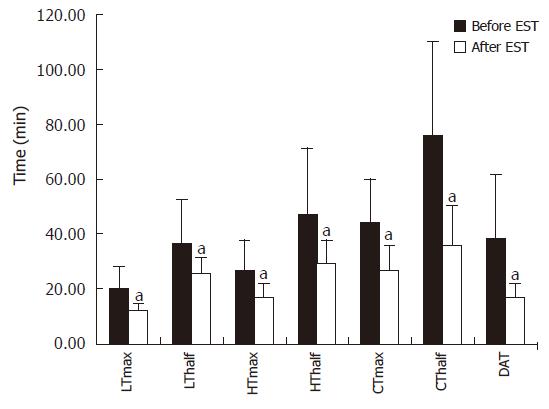

Thirty-five out of 40 patients with definite SOD (SODIand ESOM positive) were followed up after EST with QHBS and a repeated questionnaire. The median follow up time was 7.5 mo. When the post-EST results of QHBS were compared to the baseline QHBS study (before EST) we detected significant acceleration of all measured quantitative scintigraphic parameters corresponding to both hepatic secretion and transpapillary bile flow (Figure 5). As expected, the EST induced acceleration of the transpapillary bile flow caused a dramatic improvement in the parameters of CBD emptying (Tmax and Thalf), and also the DAT. Based on the comparison of VASs from the pre- and post-EST questionnaires, an impressive and highly significant improvement in the severity scores of abdominal pain was established (Figure 6), which was an obvious demonstration of the therapeutic benefit of EST in these patients with definite SOD. It must be stressed that despite homogenous improvement of biliary pain after endoscopic therapy, only 15 of 35 patients became completely free of pain after EST.

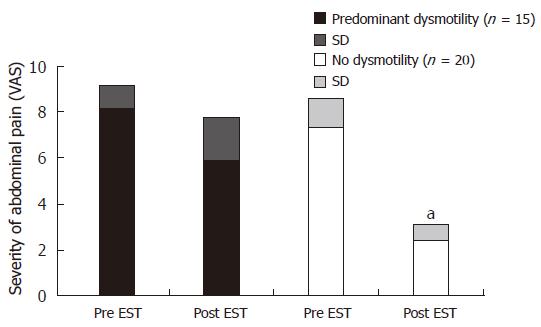

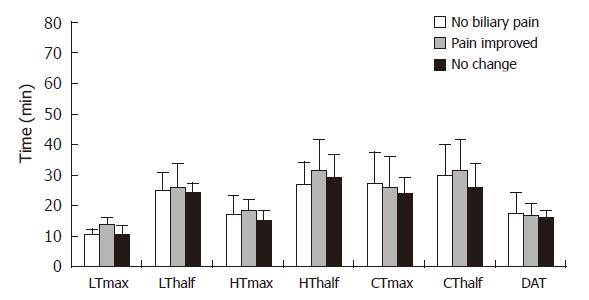

Finally, we categorized our patients based on initial presentation of dyspeptic symptoms into two groups: no or minimal dysmotility in 20 patients (less than 50% of total dysmotility scores according to the baseline questionnaire), and severe dysmotility in 15 patients (more than 50% of total dysmotility scores on the baseline questionnaire). Interestingly the severity of dyspeptic symptoms before EST was significantly correlated with the symptomatic failure of endoscopic therapy. In fact, we have demonstrated that post-EST severity of abdominal pain based on VASs was significantly higher in those patients with predominant dyspepsia at initial presentation as compared to those without dyspeptic symptoms (Figure 7). This difference in the post-EST outcome was not induced by possible endoscopic technical problems or patient-to-patient variation of the completeness of EST, since the analysis of post-EST QHBS parameters demonstrated no significant differences of these patient groups (Figure 8). No statistical differences were found in the prevalence of gastritis and H pylori infection between patients with no or minimal versus predominant dysmotility scores: 80% and 26% versus 64% and 27%, respectively. In fact, patients with predominant dysmotility scores had a lower frequency of antral gastritis detected by upper GI endoscopy.

Although there was a tendency for higher psychogenic vulnerability in those patients with definite SOD (SODIand ESOM positive SOD groups), no significant differences were detected when the results of patients were compared to asymptomatic cholecystectomized controls or those with CBD stone. Interestingly, the highest scores of symptom-stress association was detected in those patients belonged to the ESOM positive SOD group, but the patient population was not large enough to reach the level of significance.

Historically, transduodenal biliary sphincteroplasty with transampullary septoplasty has been recommended for the therapy of SOD with a reported symptomatic benefit in 60%-70% of patients during a 1 to 10 years’ follow-up[9]. Because of better patient tolerance, lower cost and less long-term re-stenosis endoscopic therapy has widely replaced surgical therapy. According to recent follow-up studies, EST produced a symptomatic relief in 55%-93% of patients with SOD and elevated SO basal pressure documented on ESOM[10-13]. This wide variation in therapeutic response after EST may reflect variations in patient groups treated, but more importantly, differences in criteria used to determine the benefit. Only a few studies evaluated the percentage of improvement after EST in patients with SOD[10,13], but most studies in the literature have applied only qualitative endpoints of symptomatic relief[3-5,11,12]. In the present study, we analysed the effect of EST on the severity scores of abdominal pain assessed by VAS, which demonstrated a homogenous and highly significant improvement in severity scores after EST in patients with definite SOD. In contrary, only 43% of these definite SOD patients became completely pain free after EST. Similar to the findings of Linder et al[6], our study clearly demonstrates that although EST does evoke a pain score reduction, complete pain relief is a relatively rare and fortunate outcome in these postcholecystectomy patients. This may be explained by the fact, that similar to patients with irritable bowel syndrome and other chronic functional pain syndromes of GI tract, the pathogenic mechanism of pain in SOD patients is more complex. Dysmotility of the SO is probably only one of the pathogenic components that are frequently accompanied by abnormalities of central nervous system, such as visceral hyperalgesia and hypersensitivity of the sensory receptors.

QHBS is a useful non-invasive method in the diagnosis of SOD by visualizing the consequent partial biliary obstruction, and according to some recent data, there is a highly significant correlation between SO basal pressure and quantitative parameters of transpapillary bile emptying[8,13]. Although the equality of QHBS and ESOM is not generally accepted in the literature[14] due to problems in reproducibility and lack of standardized methodology of QHBS, it is obvious that QHBS is an optimal non-invasive screening method to assess the presence of impaired transpapillary bile flow in SOD patients. Recently, some studies unexpectedly stated that in a certain postcholecystectomy patient population abnormal QHBS is a better predictor for favourable post-EST outcome than abnormal ESOM[13,15]. QHBS has obvious advantages as compared to the traditional ERCP contrast drainage time, as it is cheaper, non-invasive, less time-consuming and prevents unnecessary repeated ERCPs in that patient group, which has an inherent high risk of post-ERCP complication[16]. Therefore, we suggest a new modified non-invasive SOD classification strategy, where patients must have an adequate biliary pain history, such as our validated questionnaire[17], some relevant LFTs, a QHBS to study bile flow, and an MRCP or endoscopic US to measure bile duct diameter. Based on these data one could be able to classify SOD patients similarly to the original Milwaukee system, but without ERCP and post-ERCP complication.

Although it is rarely mentioned and applied, QHBS is also applicable in the follow-up of SOD patients, to demonstrate the acceleration or normalization of the transpapillary bile flow after EST[13,18-20]. Similar to the study of Corazziari et al, in the present study we proved a significant acceleration of all quantitative parameters of QHBS after EST in definite SOD patients as compared to the initial study before ERCP. Interestingly, there was no correlation between the patient general symptomatic improvement or satisfaction and the normalization or improvement in QHBS parameters. Therefore, it seems that there is a patient subpopulation with definite SOD and having biliary pain accompanied with predominant dyspeptic symptoms, which has poor therapeutic response after EST and therefore a general dissatisfaction with endoscopic therapy, despite an effective and complete EST (normalization of transpapillary bile flow on QHBS) performed.

It has been demonstrated by surgical studies, that pain after cholecystectomy was significantly correlated with the concurrent presence of symptoms of dysmotility and dyspepsia[7]. Similarly, our current results demonstrated that post-EST intensity of persistent pain in patients with definite SOD was significantly more severe in the patients with predominant dyspepsia at the initial presentation. Interestingly, there was no correlation between dysmotility and dyspeptic symptoms and the prevalence of antral gastritis or Helicobacter co-infection in these patient groups. In comparison to the public data of the general population in Hungary, our patients had a higher prevalence of antral gastritis but a lower prevalence of H pylori infection. As a possible explanation, we may consider that duodenogastric bile reflux is a significant cause of gastritis in these postcholecystectomy patients, which might also partially prevent H pylori colonization[21]. Whether patients having postcholecystectomy pain are more sensitive to dysmotility and dyspeptic complaints, or they are dyspeptic in origin is unclear. Some studies suggested that the mechanism of dyspeptic symptoms after cholecystectomy might be related to the increased duodenogastric reflux[22]. However, the effect of EST on the volume of duodenogastric reflux is unclear.

In conclusion, EST evokes a significant improvement of pain severity scores in all patients with definite SOD (selected by ERCP or ESOM), but only 43% of these patients became pain free. Persistent gastrointestinal symptoms and general patient dissatisfaction are rather common findings after EST, and correlated with the presence of predominant dyspeptic symptoms at the initial presentation, however, they do not depend on the technical and functional success of EST. Application of a validated questionnaire at the patient selection for EST and the follow up can be extremely useful in all patients having postcholecystectomy syndrome.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Steinberg WM. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: a clinical controversy. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1409-1415. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Csendes A, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P, Oster MJ, Ornsholt J, Amdrup E. Pressure measurements in the biliary and pancreatic duct systems in controls and in patients with gallstones, previous cholecystectomy, or common bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:1203-1210. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Toouli J, Dodds WJ, Venu RP. A prospective randomized study of the efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy for patients with presumptive sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:1086. |

| 4. | Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, Toouli J, Venu RP. The efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy after cholecystectomy in patients with sphincter-of-Oddi dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:82-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Neoptolemos JP, Bailey IS, Carr-Locke DL. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: results of treatment by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1988;75:454-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Linder JD, Klapow JC, Linder SD, Wilcox CM. Incomplete response to endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: evidence for a chronic pain disorder. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1738-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Middelfart HV, Kristensen JU, Laursen CN, Qvist N, Højgaard L, Funch-Jensen P, Kehlet H. Pain and dyspepsia after elective and acute cholecystectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:10-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Madácsy L, Middelfart HV, Matzen P, Hojgaard L, Funch-Jensen P. Quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy and endoscopic sphincter of Oddi manometry in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: assessment of flow-pressure relationship in the biliary tract. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:777-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moody FG, Vecchio R, Calabuig R, Runkel N. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty with transampullary septectomy for stenosing papillitis. Am J Surg. 1991;161:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Botoman VA, Kozarek RA, Novell LA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ, Wechter DG, Neal LA. Long-term outcome after endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with biliary colic and suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:165-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bozkurt T, Orth KH, Butsch B, Lux G. Long-term clinical outcome of post-cholecystectomy patients with biliary-type pain: results of manometry, non-invasive techniques and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:245-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toouli J, Roberts-Thomson IC, Kellow J, Dowsett J, Saccone GT, Evans P, Jeans P, Cox M, Anderson P, Worthley C. Manometry based randomised trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2000;46:98-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cicala M, Habib FI, Vavassori P, Pallotta N, Schillaci O, Costamagna G, Guarino MP, Scopinaro F, Fiocca F, Torsoli A. Outcome of endoscopic sphincterotomy in post cholecystectomy patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction as predicted by manometry and quantitative choledochoscintigraphy. Gut. 2002;50:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Craig AG, Peter D, Saccone GT, Ziesing P, Wycherley A, Toouli J. Scintigraphy versus manometry in patients with suspected biliary sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2003;52:352-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wehrmann T, Wiemer K, Lembcke B, Caspary WF, Jung M. Do patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction benefit from endoscopic sphincterotomy A 5-year prospective trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:251-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bertalan V, Madácsy L, Pávics L, Lonovics J. Clinical and scintigraphic assessment of the effectiveness of endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:327-369. A3 (Abstract). |

| 18. | Farup PG, Tjora S. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dynamic cholescintigraphy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with papillotomy in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:956-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fullarton GM, Hilditch T, Campbell A, Murray WR. Clinical and scintigraphic assessment of the role of endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 1990;31:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shaffer EA, Hershfield NB, Logan K, Kloiber R. Cholescintigraphic detection of functional obstruction of the sphincter of Oddi. Effect of papillotomy. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:728-733. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Karat D, Griffin SM. Helicobacter pylori and surgery. Bile reflux is important in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. BMJ. 1998;317:679; author reply 680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wilson P, Jamieson JR, Hinder RA, Anselmino M, Perdikis G, Ueda RK, DeMeester TR. Pathologic duodenogastric reflux associated with persistence of symptoms after cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1995;117:421-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |