Published online Oct 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6564

Revised: April 12, 2006

Accepted: May 22, 2006

Published online: October 28, 2006

A rare case of pseudo-Budd-Chiari Syndrome in a patient with decompensated alcoholic liver disease is reported. Although clinical and radiological findings suggested Budd-Chiari Syndrome, the liver biopsy revealed micronodular cirrhosis and absence of histological signs of hepatic outflow obstruction.

- Citation: Robles-Medranda C, Lukashok H, Biccas B, Pannain VL, Fogaça HS. Budd-Chiari like syndrome in decompensated alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(40): 6564-6566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i40/6564.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6564

Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BCS) is a rare, heterogeneous and potentially lethal condition caused by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract[1], situated anywhere between the small hepatic venules until the right atrium[2]. In Western countries, thrombosis from multiples causes is the predominant factor in the etiology of BCS[3]. The correct diagnosis is very important for the therapeutic approach. Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide evidence of hepatic vein (HV) thrombosis, with different specificity and sensitivity[4-7].

Pseudo-BCS is a condition which until now has not been well known. Only four reports were found in the literature and all of these concerned patients with a mechanical compression of the hepatic outflow due to an enlarged liver and liver cirrhosis.

The diagnosis of pseudo-BCS is difficult, because clinical and radiological findings are extremely similar to BCS, making invasive methods necessary.

We report a case of presumed BCS in a patient with alcoholic liver disease and emphasize the importance of the differential diagnosis for the correct management of these patients.

A 49-year-old female was admitted to our hospital with a 6-mo history of abdominal pain, progressive ascites, weight loss, anorexia and fatigue. There was no previous history of GI bleeding, surgery, hemotransfusions or spontaneous abortion. Also, she denied the use of oral contraceptives. Right up until admission day, she had consumed excessive amounts of alcohol for over 8 years. On physical examination we found mild jaundice, anemia, spider nevi, palmar erythema, hepatomegaly of 16 cm below the lower edge of the ribs, moderate ascites and edema. A systolic ejection murmur at the abdominal right upper quadrant was also found. Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation was normal. There was no jugular venous distention or pulsatile liver. Laboratory results are listed in Table 1.

| Admission day | Discharge day | Normal values | |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 9.7 | 11.0 | 12.0-16.0 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 108.1 | 103 | 80.0-96.0 |

| Leukocytes (/mm3) | 21800 | 10100 | 4000-11000 |

| Platelets (mil/mm3) | 306 | 250 | 140-360 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 17.6 | 15.2 | 13 |

| INR | 1.52 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.4 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 135 | 44 | 15-37 |

| Alanin aminotransferase (U/L) | 32.7 | 40 | 30-65 |

| Gamma-GT (U/L) | 907 | 312 | 5-85 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.73 | 1.4 | 0-1.0 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 24 | 36 | 34-50 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6-1.3 |

| Alkaline fosfatase (U/L) | 217 | 118 | 50-136 |

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was diagnosed and treated. During endoscopy, three small esophageal varices were found. Doppler ultrasound revealed gross hepatomegaly 20 cm, with only a narrowed middle HV visible and a tributary branch. Absence of flow in the HV was reported. The CT-scan showed the massive hepatomegaly with irregular distribution of contrast, enlarged caudate lobe, and contrast hypercaptation at the left hepatic lobe.

The possibility of hepatocarcinoma plus BCS was considered. Serum viral markers were all negative and α-fetoprotein level was normal (4.61 U/mL).

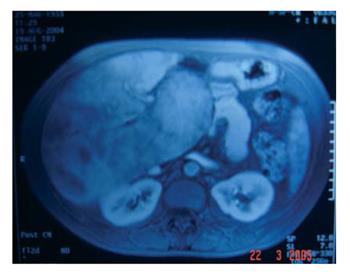

MRI examination suggested the diagnosis of BCS due to patchy enhancement, absence of left and right HV and a narrowed middle HV with two narrowed tributary branches. An arterio-portal shunt was seen and hepatocarcinoma was excluded (Figure 1).

The diagnosis of BCS was made with a high degree of certainty by radiological exams. The search for hyper-coagulable states was all negative.

Due to the patient’s previous history and clinical condition, a liver biopsy was performed in order to clarify the extent of liver damage due to alcohol abuse as well as venous occlusion.

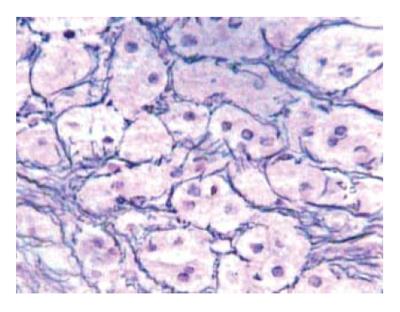

The liver biopsy showed micronodular cirrhosis, perisinusoidal and pericellular fibrosis (Figure 2). There was neither pericentral congestion nor other histological signs of hepatic outflow congestion and the use of anticoagulant therapy was not indicated. The venography was not performed due to the results of the liver biopsy.

The patient was discharged four weeks after admission with improvement of her clinical condition and laboratory results (Table 1).

BCS is a rare disease, varied in cause, presentation and progression, with different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. The radiological methods are part of the diagnostic work-up for BCS[1,8].

The first-line test is Doppler ultrasound of the liver[1] that has a sensitivity of 87.5% in the diagnosis of BCS[4]. The presence of a caudate vein equal or larger than 3 mm in diameter[9] or abnormalities in the flow of the HV outflow tract are suggestive of BCS[5,10].

MRI is the second-line test for BCS[1]. It permits differentiation between all forms of BCS[11]. Due to the high cost and low availability of this test, MRI is only recommended when the diagnosis is not clear after Doppler ultrasound[1,8,12].

A CT-scan may show an enlargement of the liver (caudate lobe), with patchy enhancement after contrast; but with indeterminate results due to false-positive in 50% of the cases[5,7]. Combination of the three techniques in the appropriate clinical setting increases sensitivity to 80%-90%[13].

In accordance with international guidelines, in BCS, liver biopsy and venography of hepatic veins are indicated when the diagnosis remains uncertain[1,14]. The third-line investigation is liver biopsy, which provides information for important differential diagnoses[14]. In current practice venography is rarely considered necessary for establishing a diagnosis and is carried out only when treatment is being planned[1].

Clinical exams and radiological testing strongly indicated that our patient was suffering from BCS. Due to the radiological results during the clinical evolution, it was no necessary to perform the venography. However, when the possible causes of BCS in our patient were extensively sought, by other means, all of them turned out to be negative.

The hypothesis of hepatocarcinoma was made due to the findings in the CT-scan. But this, too, was excluded after the MRI showed an arterio-portal shunt. It is well known that arterio-portal shunts can be present in a cirrhotic liver and confuse the diagnosis with hepatocarcinoma[15], as was the case in our patient.

Hypercoagulable states and thrombosis of other causes represent more than 75% of the etiology in patients with BCS[8]. Other authors suggest that more than 85% of idiopathic causes of BCS are due to myeloproliferative disorders[16,17].

One doubt in this case was the possibility that alcoholic intake could have been the cause of this BCS or in some way be associated with it. Two reports in the literature show this rare association[13,18].

Shankel et al in 1987 described a patient with BCS and alcoholic liver disease. The patient presented both inferior vena cava (IVC) and nephrotic syndromes. In spite of the BCS diagnosis, absence of thrombus and only a mechanical compression of the IVC was found at autopsy[18].

The second report was made by Janssen et al, fifteen years later. It described three patients with alcoholic liver disease and BCS, without any thrombotic occlusion. These cases were denominated pseudo-BCS[13].

Another two cases of pseudo-BCS were reported in association with liver cirrhosis of unknown causes, without HV occlusion findings[19,20].

Dhawan et al in 1978, described a patient with clinical and radiological findings of BCS and concomitant liver cirrhosis. A complete constriction of the right HV and a narrowed left HV were shown to be present due to the hypertrophy of the left lobe of the liver and a regenerative nodule. No thrombotic occlusions were seen at the autopsy[19]. This was the first paper to introduce the term pseudo-BCS.

Rector et al two years later, also reported a patient with liver cirrhosis, probably by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and BCS. A distortion of the IVC caused by cirrhosis and increased abdominal pressure suggested BCS due to membranous obstruction, but no thrombus or membranous occlusion was found[20].

All the cases reported had similar clinical, laboratory and radiological features and diagnostics.

Some of the described patients had a good evolution after alcohol withdrawal[13,18], including our patient. The other patients had fatal outcomes because of severe hepatic damage due to excessive alcohol intake or advanced liver disease[18,19]. One patient died after unnecessary anticoagulant therapy[13], which worsened the coagulation profile. No patients had pericentral congestion nor histological signs of hepatic outflow obstruction characteristic of BCS. A mechanical compression of the hepatic outflow due to an enlarged liver was seen in all cases. Histological changes in the architecture of the small hepatic veins were also observed in our patient.

Structural lesions of the hepatic venules, such as veno-occlusive changes, perivenular fibrosis and lymphocytic phlebitis have been well documented in patients with alcoholic liver disease[21].

Probably the structural lesions at the hepatic venules in association with mechanical compression due to anatomic abnormalities caused by an enlarged liver contributed to the misleading picture of BCS in these patients.

In conclusion the alcoholic steatohepatitis with liver cirrhosis can show a BC-like syndrome. Patients with this rare association denominated pseudo-BCS should be extensively investigated because management will depend on the correct diagnosis. The treatment of pseudo-BCS caused by alcoholic liver disease consists basically in discontinuing alcohol ingestion and generally is associated with a good prognosis.

We are indebted to David E Lukashok, MA.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Valla DC. The diagnosis and management of the Budd-Chiari syndrome: consensus and controversies. Hepatology. 2003;38:793-803. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ludwig J, Hashimoto E, McGill DB, van Heerden JA. Classification of hepatic venous outflow obstruction: ambiguous terminology of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okuda K, Kage M, Shrestha SM. Proposal of a new nomenclature for Budd-Chiari syndrome: hepatic vein thrombosis versus thrombosis of the inferior vena cava at its hepatic portion. Hepatology. 1998;28:1191-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bolondi L, Gaiani S, Li Bassi S, Zironi G, Bonino F, Brunetto M, Barbara L. Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome by pulsed Doppler ultrasound. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1324-1331. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Miller WJ, Federle MP, Straub WH, Davis PL. Budd-Chiari syndrome: imaging with pathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soyer P, Rabenandrasana A, Barge J, Laissy JP, Zeitoun G, Hay JM, Levesque M. MRI of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mori H, Maeda H, Fukuda T, Miyake H, Aikawa H, Maeda T, Nakashima A, Isomoto I, Hayashi K. Acute thrombosis of the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome: CT demonstration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:987-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bargalló X, Gilabert R, Nicolau C, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Brú C. Sonography of the caudate vein: value in diagnosing Budd-Chiari syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1641-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ohta M, Hashizume M, Tomikawa M, Ueno K, Tanoue K, Sugimachi K. Analysis of hepatic vein waveform by Doppler ultrasonography in 100 patients with portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:170-175. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Noone TC, Semelka RC, Siegelman ES, Balci NC, Hussain SM, Kim PN, Mitchell DG. Budd-Chiari syndrome: spectrum of appearances of acute, subacute, and chronic disease with magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kane R, Eustace S. Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome: comparison between sonography and MR angiography. Radiology. 1995;195:117-121. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Janssen HL, Tan AC, Tilanus HW, Metselaar HJ, Zondervan PE, Schalm SW. Pseudo-Budd-Chiari Syndrome: decompensated alcoholic liver disease mimicking hepatic venous outflow obstruction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:810-812. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Janssen HL, Garcia-Pagan JC, Elias E, Mentha G, Hadengue A, Valla DC. Budd-Chiari syndrome: a review by an expert panel. J Hepatol. 2003;38:364-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tamura S, Kihara Y, Yuki Y, Sugimura H, Shimizu T, Adjei ON, Watanabe K. Pseudo lesions on CTAP secondary to arterio-portal shunts. Clin Imaging. 1997;21:359-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Valla D, Casadevall N, Lacombe C, Varet B, Goldwasser E, Franco D, Maillard JN, Pariente EA, Leporrier M, Rueff B. Primary myeloproliferative disorder and hepatic vein thrombosis. A prospective study of erythroid colony formation in vitro in 20 patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:329-334. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pagliuca A, Mufti GJ, Janossa-Tahernia M, Eridani S, Westwood NB, Thumpston J, Sawyer B, Sturgess R, Williams R. In vitro colony culture and chromosomal studies in hepatic and portal vein thrombosis--possible evidence of an occult myeloproliferative state. Q J Med. 1990;76:981-989. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Dhawan VM, Sziklas JJ, Spencer RP. Pseudo-Budd-Chiari syndrome. Clin Nucl Med. 1978;3:30-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shankel S. Budd-Chiari and the nephrotic syndromes secondary to massive hepatomegaly. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:155-158. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Rector WG Jr. Pseudo-Budd-Chiari syndrome: extrinsic deformity of the intrahepatic inferior vena cava mimicking membranous obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:88-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Occlusive venous lesions in alcoholic liver disease. A study of 200 cases. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:786-796. [PubMed] |