Published online Oct 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6527

Revised: July 12, 2006

Accepted: July 30, 2006

Published online: October 28, 2006

AIM: To detect the patients with and without pan-creaticobiliary maljunction who had pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels.

METHODS: Ninety-six patients, who had diffuse thickness (> 3 mm) of the gallbladder wall and were suspected of having a pancreaticobiliary maljunction on ultrasonography, were prospectively subjected to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and bile in the common bile duct was sampled. Among them, patients, who had extremely high biliary amylase levels (>10 000 IU/L), underwent cholecystectomy, and the clinicopathological findings of those patients with and without pancreaticobiliary maljunction were examined.

RESULTS: Seventeen patients had biliary amylase levels in the common bile duct above 10 000 IU/L, including 11 with pancreaticobiliary maljunction and 6 without pancreaticobiliary maljunction. The occurrence of gallbladder carcinoma was 45.5% (5/11) in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction, and 50% (3/6) in those without pancreaticobiliary maljunction.

CONCLUSION: Pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels and associated gallbladder carcinoma could be identified in patients with and without pancreaticobiliary maljunction, and those patients might be detected by ultrasonography and bile sampling.

- Citation: Sai JK, Suyama M, Kubokawa Y, Nobukawa B. Gallbladder carcinoma associated with pancreatobiliary reflux. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(40): 6527-6530

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i40/6527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6527

It is well known that pancreatobiliary reflux is an important risk factor for the carcinogenesis of the biliary system in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM)[1,2], which is a congenital anomaly defined as an abnormal union of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct that is located outside the duodenal wall where a sphincter system is not present and pancreatic juice freely regurgitates into the biliary tract through the communication[3].

Recently, we reported that pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels can occur not only in patients with PBM, but also in those without PBM[4,5], although the latter condition is not well known yet. In the present study, we tried to detect the patients, who had pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels, and examined the clinicopathological findings of those patients.

Between March 2002 and February 2006, 96 patients, who had diffuse thickness of the gallbladder wall above 3 mm and were suspected of having pancreaticobiliary maljunction on ultrasonography, were prospectively subjected to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Bile in the common bile duct was sampled as follows and biliary amylase levels were measured in those patients. After selective insertion of an ERCP catheter into the bile duct, bile was aspirated from the common bile duct at a depth of 5 cm. To avoid contamination with pancreatic juice, the first 5 mL of the aspirated bile was not used to measure biliary amylase levels, and another sample of bile was obtained for the measurement. In all patients, serum amylase was measured within 48 h before cholecystectomy. Amylase in the serum and bile was measured by an enzymatic method using 3-ketobutylidene-2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl- maltopentaoside (Diacolor Neonate, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) as the substrate[6]. The normal range for serum amylase in our institution is 130 to 400 IU/L. We defined extremely high biliary amylase levels as those above 10 000 IU/L, and patients with extremely high biliary amylase levels were indicated for cholecystectomy. Patients having bile duct stenosis, filling defect in the bile duct, including choledocholithiasis on ERCP, were excluded from the present study, because their biliary amylase levels in the common bile duct would not correctly reflect pancreatobiliary reflux.

Patients were divided into those with PBM and without PBM (non-PBM). On ERCP images, the two ducts were always communicated in PBM patients, but not in non-PBM patients due to the sphincter contraction. The length of the common channel was measured on ERCP images corrected for magnification using the diameter of the endoscope as a reference.

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

All specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The gallbladder tissues embedded in paraffin were cut into 4-μm serial sections, and the gallbladder mucosa was histologically examined using sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). All specimens were diagnosed based on light microscopic findings. Carcinoma of the gallbladder was diagnosed according to the criteria reported by Albores-Saavedra et al[7].

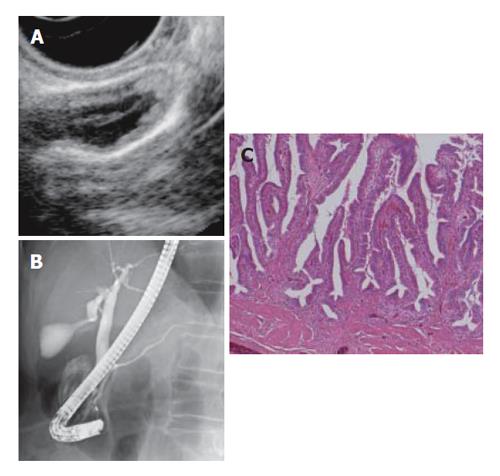

Serum amylase was within 600 IU/L in all patients. Among the 96 patients who underwent ERCP, bile was successfully sampled in 87 patients; four patients underwent unsuccessful ERCP, two had bile duct stenosis, three had choledocholithiasis, and these patients were excluded from the present study. Consequently, 17 patients had extremely high biliary amylase levels in the common bile duct above 10 000 IU/L, including 11 PBM patients and 6 non-PBM patients. Among the PBM patients, 4 had a choledocal cyst. All patients with biliary amylase levels above 10 000 IU/L underwent cholecystectomy. The main clinical characteristics of PBM and non-PBM patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The occurrence of gallbladder carcinoma was 45.5% (5/11) in PBM patients, and 50% (3/6) in non-PBM patients. PBM patients included 1 carcinoma limited within the mucosa, while non-PBM patients included 2 (Table 1, Figure 1).

| Age | Sex | Biliary amylase(IU/L) | Common channel length (mm) | Pathology | Depth of invasion | GB stone | Choledocal cyst | |

| 1 | 56 | M | 47 190 | 7 | Hyperplasia | + | - | |

| 2 | 69 | F | 27 038 | 8 | Hyperplasia | + | - | |

| 3 | 63 | F | 61 710 | 4 | Hyperplasia | - | - | |

| 4 | 53 | F | 52 600 | 8 | ca | m | - | - |

| 5 | 68 | F | 84 700 | 9 | ca | m | - | - |

| 6 | 70 | F | 64 260 | 4 | ca | ss | - | - |

| 7 | 65 | F | 12 030 | 18 | chr-itis | + | + | |

| 8 | 74 | F | 153 000 | 16 | chr-itis | + | - | |

| 9 | 63 | M | 136 400 | 48 | ADM | - | + | |

| 10 | 34 | F | 145 000 | 15 | Hyperplasia | + | - | |

| 11 | 46 | F | 103 500 | 26 | Hyperplasia | - | - | |

| 12 | 40 | F | 126 900 | 28 | Hyperplasia | + | + | |

| 13 | 47 | M | 95 400 | 19 | ca | m | - | - |

| 14 | 54 | F | 132 180 | 27 | ca | ss | - | - |

| 15 | 64 | F | 177 520 | 24 | ca | ss | - | - |

| 16 | 75 | F | 26 510 | 20 | ca | ss | - | - |

| 17 | 57 | F | 21 100 | 19 | ca | ss | - | - |

| non-PBM(n = 6) | PBM (n = 11) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.2 ± 7.2 | 54.1 ± 12 |

| Female (number) | 5/6 (83%) | 9/11 (82%) |

| CBD-Amy (mean ± SD) IU/L | 56 250 ± 19 246 | 102 686 ± 57 660 |

| Cholecystolithiasis (number) | 2/6 (33%) | 4/11 (36%) |

| Length of the common channel (mean ± SD) mm | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 23.6 ± 9.2 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma (number) | 3/6 (50%) | 5/11 (46%) |

Gallbladder carcinoma is known to carry a poor prognosis[8]. It is therefore essential to identify patients at a high risk for developing gallbladder carcinoma[9]. The risk of gallbladder carcinoma associated with PBM is substantial; it was reported that the occurrence of biliary cancer in 388 PBM patients without biliary dilatation was 37.9%, including 93.2% with gallbladder carcinoma and 6.8% with bile duct cancer, while that in 1239 PBM patients with choledocal cyst was 10.6%, including 33.6% with extrahepatic bile duct cancer and 64.9% with gallbladder carcinoma[10]. Numerous studies have shown that pancreatobiliary reflux is a major risk factor for biliary carcinogenesis in patients with PBM; the mixture of bile and pancreatic juice can induce chronic inflammation and genetic alterations and increase cellular proliferation of the biliary tract epithelium, leading to hyperplasia, dysplasia and ultimately carcinoma of the biliary tract mucosa[11,12].

Pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels was also identified in non-PBM patients in the present study, and 50% of those patients had gallbladder carcinoma. Furthermore it included gallbladder carcinoma limited within the mucosa, and thus detection of pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels might allow management for gallbladder carcinoma at an early stage.

In order to identify pancreatobiliary reflux pre-operatively, secretin-injection magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an option that has proved useful as we have previously reported[4,5], although high amylase levels in the bile sampled during ERCP is a direct evidence of pancreatobiliary reflux. One of the characteristic findings of ultrasonography associated with pancreaticobiliary maljunction was reported as diffuse thickness of the gallbladder wall above 3 mm, that might reflect mucosal change associated with pancreatobiliary reflux including chronic inflammation and increased cellular proliferation of the gallbladder mucosa[13]. In the present study, ultrasonographic finding also proved useful to diagnose non-PBM patients with extremely high biliary amylase levels, although the finding was non-specific and was seen in other diseases including chronic cholecystitis with or without gallstone, adenomyomatosis, and liver cirrhosis[13].

Reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract is influenced by the function of Oddi’s sphincter and the form of the junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct[14]. One of the mechanisms of pancreatobiliary reflux in non-PBM patients could be a long common channel. Actually, 67% (4/6) of non-PBM patients had a long common channel more than 7 mm in the present study. Misra et al reported that a common channel more than 8 mm in length was seen more frequently in patients with gallbladder carcinoma (38%) compared with normal subjects (3%) or patients with gallstones (1%)[15]. Kamisawa et al also reported that the occurrence of gallbladder carcinoma in non- PBM patients with a common channel of more than 6 mm in length was 12%, being significantly higher than that in controls[16]. They speculated that the longer common channel could be associated with a higher occurrence and a more significant degree of pancreatobiliary reflux, which might be the cause of gallbladder carcinoma, although they did not measure the biliary amylase levels in their study. Another mechanism of pancreatobiliary reflux in non-PBM patients, especially in our two patients with a common channel of 4 mm, might be the dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, however, the precise mechanism of pancreatobiliary reflux in non-PBM patients should be further clarified in future studies.

In conclusion, pancreatobiliary reflux with extremely high biliary amylase levels and associated gallbladder carcinoma could be identified in patients with and without pancreaticobiliary maljunction, and those patients might be detected by ultrasonography and bile sampling.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Kimura K, Ohto M, Saisho H, Unozawa T, Tsuchiya Y, Morita M, Ebara M, Matsutani S, Okuda K. Association of gallbladder carcinoma and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1258-1265. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Nagata E, Sakai K, Kinoshita H, Kobayashi Y. The relation between carcinoma of the gallbladder and an anomalous connection between the choledochus and the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1985;202:182-190. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hep Bil Pancr Surg. 1994;1:219-221. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sai JK, Ariyama J, Suyama M, Kubokawa Y, Sato N. Occult regurgitation of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract: diagnosis with secretin injection magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:929-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sai JK, Suyama M, Kubokawa Y, Tadokoro H, Sato N, Maehara T, Iida Y, Kojima K. Occult pancreatobiliary reflux in patients with a normal pancreaticobiliary junction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Teshima S, Hayashi Y, Emi S, Ishimaru K. Determination of alpha-amylase using a new blocked substrate (3-ketobutylidene beta-2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl-maltopentaoside). Clin Chim Acta. 1991;199:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the gallbladder, extrahepatic bile duct, and ampulla of Vater. Atlas of tumor pathology. 3rd series, fascicle 27. Washington, D.C. : Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2000; 51-113. |

| 8. | Bengmark S, Jeppsson B. Tumors of the gallbladder. In: Textbook of Gastroenterology, 2nd ed. T Yamada ed. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott 1995; 2739-2744. |

| 9. | Sheth S, Bedford A, Chopra S. Primary gallbladder cancer: recognition of risk factors and the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1402-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, Okada A, Katoh T, Kawaharada Y, Shimada H, Takamatsu H, Miyake H, Todani T. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:345-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hanada K, Itoh M, Fujii K, Tsuchida A, Hirata M, Ishimaru S, Iwao T, Eguchi N, Kajiyama G. Pathology and cellular kinetics of gallbladder with an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1007-1011. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Matsubara T, Sakurai Y, Sasayama Y, Hori H, Ochiai M, Funabiki T, Matsumoto K, Hirono I. K-ras point mutations in cancerous and noncancerous biliary epithelium in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Cancer. 1996;77:1752-1757. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Yamao K, Mizutani S, Nakazawa S, Inui K, Kanemaki N, Miyoshi H, Segawa K, Zenda H, Kato T. Prospective study of the detection of anomalous connections of pancreatobiliary ducts during routine medical examinations. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1238-1245. [PubMed] |

| 14. | BOYDEN EA. The anatomy of the choledochoduodenal junction in man. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;104:641-652. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Misra SP, Gulati P, Thorat VK, Vij JC, Anand BS. Pancreaticobiliary ductal union in biliary diseases. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic study. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:907-912. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kamisawa T, Amemiya K, Tu Y, Egawa N, Sakaki N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Munakata A. Clinical significance of a long common channel. Pancreatology. 2002;2:122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |