Published online Oct 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6401

Revised: March 8, 2006

Accepted: March 27, 2006

Published online: October 21, 2006

A 55-year old male patient was diagnosed with strongy-loides hyper-infection with stool analysis and intestinal biopsy shortly after his chemotherapy for myeloma. He was commenced on albendazole anthelmintic therapy. After initiation of the treatment he suffered life-threatening gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Repeated endoscopies showed diffuse multi-focal intestinal bleeding. The patient required huge amounts of red blood cells and plasma transfusions and correction of haemostasis with recombinant activated factor VII. Abdominal aorto-angiography showed numerous micro-aneurysms (‘berry aneurysms’) in the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries’ territories. While the biopsy taken prior to the treatment with albendazole did not show evidence of vasculitis, the biopsy taken after initiation of therapy revealed leukoclastic aggregations around the vessels. These findings suggest that, in addition to direct destruction of the mucosa, vasculitis could be an important additive factor causing the massive GI bleeding during the anthelmintic treatment. This might result from substances released by the worms that have been killed with anthelmintic therapy. Current guidelines advise steroids to be tapered and stopped in case of systematic parasitic infections as they might reduce immunity and precipitate parasitic hyper-infection. In our opinion, steroid therapy might be of value in the management of strongyloides hyper-infection related vasculitis, in addition to the anthelmintic treatment. Indeed, steroid therapy of vasculitis with other means of supportive care resulted in cessation of the bleeding and recovery of the patient.

- Citation: Csermely L, Jaafar H, Kristensen J, Castella A, Gorka W, Chebli AA, Trab F, Alizadeh H, Hunyady B. Strongyloides hyper-infection causing life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(39): 6401-6404

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i39/6401.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6401

Chemotherapy of malignancies as well as immunosuppression of immunological disorders is frequently complicated with severe infections, including bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic infections. We present here a case of life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding related to strongyloides hyper-infection as a consequence of chemotherapy for myeloma.

A 55-year-old male patient was diagnosed with kappa light chain myeloma stage III-B based on the Salmon-Durei staging system. The patient started chemotherapy according to the VAD protocol[1,2], consisting of vincristine, doxorubicin and high dose dexamethasone along with zolendronic acid every 4 wk. After he received three full courses of chemotherapy the patient was admitted to the hospital for generalized fatigue, and fever with signs and symptoms of chest infection. Laboratory investigations showed haemoglobin of 105 g/L, white blood cell count of 5.5 × 109/L (neutrophils 0.84, lymphocytes 0.11, monocytes 0.02, eosinophils 0.00, basophils 0.00, bands 0.03), and platelet counts of 1.91 × 1011/L. His blood chemistry and coagulation profile were within normal limits except a low albumin level of 29 g/L (normal: 35-48 g/L). Chest X-ray showed no obvious abnormality. After obtaining blood and urine cultures ceftazidime therapy was started with an assumption of respiratory tract infection. For the following two days the patient kept a spiking fever which was associated with progressive pulmonary symptoms (dry cough and dyspnea). His oxygen saturation dropped to 90% in room air, and a moderate eosinophilia was observed: neutrophils 0.76, lymphocytes 0.12, monocytes 0.02, eosinophils 0.08, basophils 0.00, bands 0.02. On physical examination he had bilateral wheezes and basal crackles. The chest X-ray was suspicious of hilar infiltrates at that time. A full cardiac assessment was done, and both ECG and echocardiography were within normal limits.

Subsequent spiral CT scan was not confirmatory for potential opportunistic chest infection, and the antibiotics however were changed to high dose septrin and levofloxacine intravenously. Serology tests for Legionella, Mycoplasma, hepatitis A, B, C, cytomegalovirus and Ebstein-Barr virus were all negative. The blood culture grew staphylococcus and for that reason the portacath of the patient was removed and vancomycin was given. In spite of these managements, the patient’s general condition did not improve. He presented soon new symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia and vomitus, associated with major metabolic disturbances (sodium 117 mmol/L [N: 136-145 mmol/L], albumin corrected calcium 1.84 mmol/L [N: 2.2-2.6 mmol/L], and albumin 21 g/L [N: 35-48 g/L]), all quite resistant to treatment. Many options in the differential diagnosis were considered including inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (urine and plasma osmolality test and CT of the brain requested) and other endocrine dysfunction (PTH, TSH, free T4, T3, cortisol levels investigated). All of these investigations showed no hormonal abnormality.

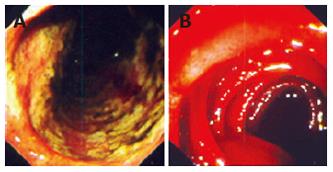

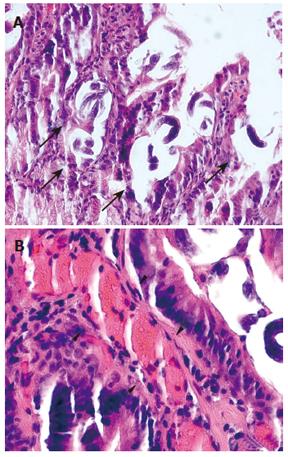

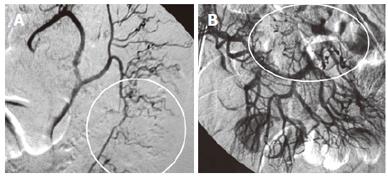

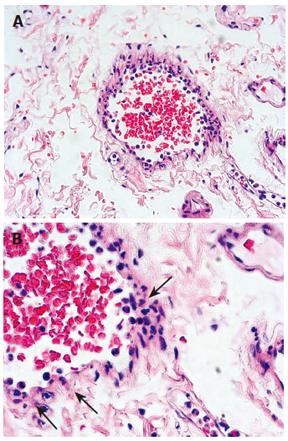

Possibilities of gastrointestinal (GI) losses were also considered (exudative enteropathies, motility disorders, etc.). Plain abdominal X-ray, barium swallow and esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) were completed. OGD showed diffuse confluent necrotic ulcerations in the stomach and the duodenum (Figure 1A). Biopsies were taken and intravenous omeprazole was started. A few days later the patient complained of epigastric pain accompanied with bilious and feculent vomitus. On examination, his abdomen was distended with decreased bowel sounds. A decubitus abdominal X-ray showed multiple fluid levels consistent with paralytic ileus. By this time, stool parasitology (Figure 2) as well as histopathology from both the duodenum (Figure 3A) and the stomach confirmed Strongiloides stercoralis helmintic infection with heavily infiltrated intestinal mucosa, but without histology criteria of vasculitis (Figure 3B). The patient received albendazole therapy (400 mg twice daily). Two days later, the patient developed massive GI bleeding with hypovolemic shock and major drop in the haemoglobin (40 g/L) requiring intensive care unit monitoring. His platelet count and coagulation profile were both normal at the first presentation of GI bleeding. Repeat OGD, magnetic resonance imaging study of the abdomen and pelvis, radio-labelled red blood cell (RBC) nuclear investigations failed to localize a specific site of the bleeding. Colonoscopy was inconclusive due to heavy continuous flow of feculent content mixed with fresh blood from the small intestine. Abdominal aorta angiography showed numerous micro-aneurysms in the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries’ territories with segmental strictures on the small intestine, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 4).

With repeated episodes of massive blood loss, during an overnight call an explorative laparotomy was decided on to localize a potentially resectable particular region of the intestine-as a desparate, life-saving procedure. During the procedure an intra-operative intestinoscopy was performed showing diffuse small intestinal bleeding (Figure 1B). No intestinal resection was done. However, as an additional proof of vasculitis at this point, intestinal biopsy revealed leukoclastic aggregations around the vessels of the mucosa (Figure 5). Screening for connective tissue diseases including immunoglobulin levels, rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear, anti-smooth muscle, and anti double-strand DNA antibodies was not suggestive of systemic autoimmune disorder. The patient was managed with huge amounts of blood transfusion, fresh frozen plasma, tranexamic acid (Cyklokaprone®), somatostatin, and, to correct secondary coagulopathy, with recombinant factor VIIa (Novoseven®). In addition, he was given antibiotics, anthelmintics drugs (albendazole and ivermectin) and steroids (dexamethasone). He required more than 120 units of RBC transfusion and 16 doses of Novoseven®. After 10 d of intensive support the bleeding gradually subsided. Stool analysis became repeatedly negative for strongyloides. An endoscopy was carried out 20 d later and showed complete recovery of the mucosa on review as well as on histopathology.

Strongyloidiasis is a worldwide infection, caused by the nematode Strongyloides stercoralis helminth[3]. This threadworm spreads in poorly sanitized areas from moist soil. It is endemic in the tropical Asia, Africa, Latin America, Southern US and Eastern Europe. In Southeast US its prevalence is as high as 4%[4,5]. Chronic infection with S. stercoralis is usually asymptomatic, but it may manifest with symptoms such as episodic creeping urticaria, epigastric crampy abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Myeloma, as well as its chemotherapy can interfere with the immune competence of the patients. In addition to more frequent bacterial, viral and fungal infections, disseminated parasitosis may develop in such situations. There is remarkable absence of cellular immune response to these invaders specifically eosinophilia[4]. In case of Strongyloides stercoralis, steroids may not only affect the host’s cellular immunity, but also mimic an endogenous parasitic-derived regulatory hormone[5,6]. Strongyloides were noticed to produce more eggs in the presence of exogenous steroids. Due to immunosuppressant therapy, there is a larger proportion of the rhabditiform larvae which mature into the filariform larvae within the host. This leads to a greater larval load and disseminated hyper-infection[5,7]. Secondary bacterial infections are also frequent complications of dissemination phase. Pulmonary symptoms of our patient at his post-chemotherapy admission to the hospital are likely to be related to pulmonary migration of the larvae during the dissemination phase.

In hyper-infection syndrome, complete disruption of the GI mucosa, ulcerations, paralytic ileus with exudative enteropathy as well as massive GI bleeding may also occur due to the direct invasion of the larvae. Profound diarrhea, malabsorption with consequent hypo-albuminemia and electrolyte disturbances were all consistent with hyper-infection related enteropathy in our patient. On the other hand, effective anthelminthic treatment in hyper-infected patients can lead to mass-destruction of intraluminal and intramural larvae and to release of huge amounts of different toxic inflammatory and vaso-active compounds[7,8]. Angiography and histopathology findings after initiation of albendazole therapy were consistent with active vasculitis in our patient, caused potentially by such compounds. For that reason we decided to maintain steroid therapy instead of rapid tapering and discontinuation of it, as advised by some experts. In our opinion, vasculitis due to helminth-derived inflammatory factors might contribute to mucosal disruption and massive GI bleeding. Steroids might reduce inflammation in such situation. Anthelmintic treatment and supportive management with transfusions of blood products and parenteral nutrition were also maintained until no more larvae could be detected in the stool. Finally, we have to emphasize the heroic multi-disciplinary efforts that led to a complete recovery of this 55 year old patient with strongyloides hyper-infection related life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding.

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Barlogie B, Smith L, Alexanian R. Effective treatment of advanced multiple myeloma refractory to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1353-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mineur P, Ménard JF, Le Loët X, Bernard JF, Grosbois B, Pollet JP, Azais I, Laporte JP, Doyen C, De Gramont A. VAD or VMBCP in multiple myeloma refractory to or relapsing after cyclophosphamide-prednisone therapy (protocol MY 85). Br J Haematol. 1998;103:512-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Strickland GT. Hunter's tropical Medicine and emerging infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott 2000; 124-128. |

| 4. | Hughes R, McGuire G. Delayed diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thomas MC, Costello SA. Disseminated strongyloidiasis arising from a single dose of dexamethasone before stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52:520-521. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Suvajdzic N, Kranjcić-Zec I, Jovanović V, Popović D, Colović M. Fatal strongyloidosis following corticosteroid therapy in a patient with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenia. Haematologia (Budap). 1999;29:323-326. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Armstrong J, Cohen J. Infectious Diseases. London: Blackwell Science 1999; 8-2-8/3. |

| 8. | Reiman S, Fisher R, Dodds C, Trinh C, Laucirica R, Whigham CJ. Mesenteric arteriographic findings in a patient with strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:635-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |