Published online Oct 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6203

Revised: February 28, 2006

Accepted: June 14, 2006

Published online: October 14, 2006

AIM: To investigate the efficacy of topical application of 0.5% nifedipine ointment in healing acute anal fissue and preventing its progress to chronicity.

METHODS: Thirty-one patients (10 males, 21 females) with acute anal fissure from September 1999 to January 2005 were treated topically with 0.5% nifedipine ointment (t.i.d.) for 8 wk. The patients were encouraged to follow a high-fiber diet and assessed at 2, 4 and 8 wk post-treatment. The healing of fissure and any side effects were recorded. The patients were subsequently followed up in the outpatient clinic for one year and contacted by phone every three months thereafter, while they were encouraged to come back if symptoms recurred.

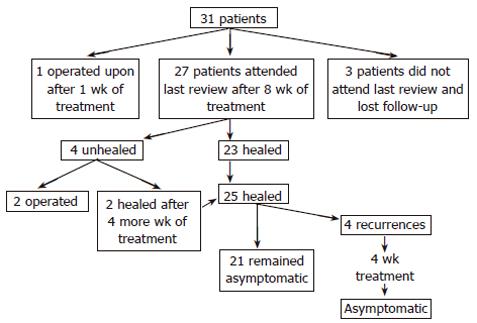

RESULTS: Twenty-seven of the 31 patients completed the 8-wk treatment course, of them 23 (85.2%) achieved a complete remission indicated by resolution of symptoms and healing of fissure. Of the remaining four unhealed patients (14.8%), 2 opted to undergo lateral sphincterotomy and the other 2 to continue therapy for four additional weeks, resulting in healing of fissure. All the 25 patients with complete remission had a mean follow-up of 22.9 ± 14 (range 6-52) mo. Recurrence of symptoms occurred in four of these 25 patients (16%) who were successfully treated with an additional 4-wk course of 0.5% nifedipine ointment. Two of the 27 (7.4%) patients who completed the 8-wk treatment presented with moderate headache as a side effect of nifedipine.

CONCLUSION: Topical 0.5% nifedipine ointment, used as an agent in chemical sphincterotomy, appears to offer a significant healing rate for acute anal fissure and might prevent its evolution to chronicity.

- Citation: Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, Beltsis A, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Katsinelos T, Papaziogas B. Aggressive treatment of acute anal fissure with 0.5% nifedipine ointment prevents its evolution to chronicity. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(38): 6203-6206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i38/6203.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6203

Anal fissure is a painful condition that affects a sizable majority of the population. The cause is controversial. However, current theories suggest that an initial traumatic tear fails to heal, because of the internal anal sphincter spasm, generating high pressure into the anal canal and leading to secondary local ischemia of the anal mucosa[1,2]. Treatment aims at improving the blood supply to the ischemic area in order to facilitate healing by reducing, if necessary, the resting anal pressure, a function of the internal anal sphincter. Traditional surgical techniques for treatment include anal dilation and partial division of the internal sphincter, which may be complicated by incontinence[3,4]. This significant complication has led to a search for alternative therapies for the treatment of anal fissure. The alternative options of “chemical sphincterotomy” include topical glyceryl trinitrate[5,6], diltiazem[7,8], botulinum toxin[9,10], bethanechol[7], indoramin[11], and nifedipine[12-14] . The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of local application of a new preparation of nifedipine ointment (0.5%) as an aggressive therapeutic modality in healing acute anal fissure and preventing its evolution to chronicity.

Thirty-one patients (10 males, 21 females, mean age 44.6± 11.9 years, range 19-69 years) with acute anal fissure participated in the study, from September 1999 to January 2005. The fissures were posterior in 27 patients (87%) and anterior in 4 patients (13%). Symptoms on presentation were anal pain in all patients (100%) and bright red bleeding per rectum in 14 patients (45.2%). The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | % | |

| Patients (n) | 31 | 100 |

| Mean age ± SD (yr) (range) | 44.6 ± 11.9 (19-69) | |

| Gender ratio (M:F) | 10:21 | 32.3:67.7 |

| Location | ||

| Posterior midline | 27 | 87.1 |

| Anterior midline | 4 | 12.9 |

| Pain | 31 | 100 |

| Bleeding | 14 | 45.2 |

| Mean follow-up ± SD (mo) (range) | 22.9 ± 14 (6-52) |

Inclusion criteria included patients with acute anal fissure aged 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria were presumed or confirmed surgery, allergy to nifedipine, associated complications warranting surgery (abscess, fistula and cancer), Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis ulcer, leukemic ulcer, HIV-related anal ulcer, cancer, and unwillingness of the patient to participate in the study. Concomitant first-to third-degree hemorrhoids were not considered an exclusion criterion.

Presence of acute anal fissure was considered if the patient presented with a history of anal pain at defecation for less than two months, that failed to resolve with conservative therapy consisting of stool softeners, high fiber diet and topical anesthetic creams prescribed by the general practitioner.

In the same time period we followed up 39 patients with acute anal fissure which was healed in only 8 patients after treatment with stool softeners and topical analgesics alone.

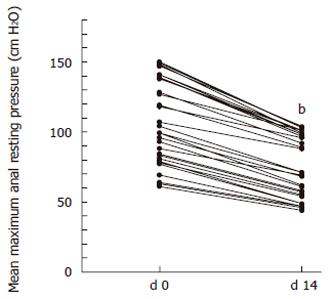

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central Hospital of Thessaloniki, and all patients signed an informed consent. Anal manometry was performed in all patients before they entered the study and after two weeks of treatment. Manometric recordings and analysis of the tracings were conducted using a water-perfusion system. The anal canal pressure was recorded in cm of water by the stationary pull-through technique, using a water-filled micro-balloon and external transducer (PVD) perfusion equipment (Medtronic Inc, Bonn, Germany). The recording and analysis of the tracings were both made by a computerized system (8 channels polygraph ID, Medtronic Polygraph with Polygram 98, version 2.2 software, Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anal resting pressures were recorded, and the mean pressure was determined by the computer.

Topical nifedipine ointment regimen was prepared by a pharmacist diluting 100 mg of nifedipine in 20 g of yellow soft paraffin to produce a preparation of 0.5%. Patients were instructed to apply the ointment circumferentially 1 cm inside the anus, near the internal anal sphincter, every 8 h for 8 wk. The preparation was kept in a cool place, inside an opaque glass container with a screw top lid, and discarded 3 wk after formulation.

Patients were not prescribed stool softeners or topical analgesic creams during the treatment. A high-fiber diet was encouraged. The patients were followed up at 2, 4, and 8 wk in the outpatient clinic. During each visit, they were asked if they had pain and bleeding on defecation, and if they had headache, dizziness, flush, rash, and incontinence. Healing of acute anal fissure was set as the primary target of our study, and defined as epithelialization achieved on d 57 of therapy. If healing occurred after the initial 8-wk period, the patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic at 3, 6, and 12 mo, or sooner if recurrent symptoms occurred. Thereafter, the patients were contacted by telephone every three mo. If symptoms recurred, the patients were encouraged to call back, and given the option to undergo treatment with 0.5% nifedipine ointment for 4 consecutive wk, and the option of operation. If they selected the last option or if symptoms persisted after the additional 4 wk treatment, the patients were referred for lateral sphincterotomy.

The paired t-test was used to evaluate the impact of nifedipine application on the mean maximal anal resting pressure (MMRP). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 10.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

The baseline MMRP was 139.6 (range 118-150) cm H2O (normal range 60-160 cm H2O) in the 10 male subjects and 90.3 (range 61-141) cm H2O (normal range 43-142 cm H2O) in the 21 female subjects. After topical application of 0.5% nifedipine ointment for 14 d, the MMRP was 100 (range 96-104) cm H2O in males and 63.6 (range 44-102) cm H2O in females (Figure 1).

The treatment outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. One patient continued to present severe anal pain in the first week of therapy and chose to be operated upon. Twenty-seven of the 31 patients attended the last review at 8 wk, of them 23 (85.2%) had complete remission. The remaining 4 (14.8%) did not heal at 8 wk and were given the option of an additional course of nifedipine treatment or the option of lateral internal sphincterotomy. Two of these four patients opted for a further course of nifedipine therapy leading to complete remission, and the other two preferred to be operated.

The 25 patients who were successfully treated with 0.5% nifedipine ointment had a mean follow-up of 22.9 ± 14 (range 6-52) mo, of them 21 (84%) remained asymptomatic and 4 (16%) had recurrences that were successfully treated with an additional 4-wk course of treatment with 0.5% nifedipine ointment. It was not possible to predict healing from the initial manometric response to 0.5% nifedipine ointment.

Two patients with a history of migraine reported moderate headache while being treated with topical nifedipine, which was treated with paracetamol. No other side effects were reported.

Oral and topical calcium channel blockers (CCBs) have recently been shown to lower the anal resting pressure by relaxing the internal anal sphincter[12-16]. The transport of calcium through the L-type calcium channels is important for the maintenance of internal anal sphincter tone[17]. As opposed to glyceryl trinitrate, which reduces resting anal tone by releasing nitric oxide, nifedipine (a calcium channel blocker) reduces the tone and spontaneous activity of the sphincter by decreasing the intracellular availability of calcium[17-19]. Oral administration of CCBs is associated with side effects such as hypotension and flushing, which may decrease compliance[20]. Topical diltiazem and nifedipine are highly effective, achieving a healing rate of 67% for diltiazem and up to 95% for nifedipine[8,12,13]. A recent randomized study by our group showed that the topical use of 0.5% nifedipine could achieve complete healing in 96.7% of the patients, not significantly different from the group treated with internal sphincterotomy[21]. However, the problem with temporary “chemical sphincterotomy” is that after treatment the anal pressure rises to pre-treatment levels, resulting in a high rate of recurrence. Recurrence has been reported in approximately 42% of patients treated with nifedipine[22]. It should be noted, however, that the above healing and recurrence rates have been reported in patients with chronic anal fissures.

Acute anal fissure in adults is thought to precede chronic fissure and to be more analogous to pediatric anal fissure in its pathologic anatomy[1]. It is commonly belied that if acute anal fissure is aggressively treated, it can be healed preventing the development of chronic fissure.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one published work investigating the efficacy of nifedipine ointment in the treatment of acute anal fissure. In the study of Antropoli et al[12], 141 patients were treated topically with 0.2% nifedipine gel, every 12 h for 3 wk. The control group consisting of 142 patients received topical 1% lidocaine and 1% hydrocortisone acetate gel. Complete remission of acute anal fissure was achieved in 95% of the nifedipine-treated patients, as opposed to 50% of the controls. The study does not report the followed up patients. In contrast to the study by Antropoli et al[12], we used 0.5% (instead of 0.2%) nifedipine ointment, the period of treatment was 8 (instead of 3) wk and we included a relatively long-term follow-up of patients of 22.9 ± 14 (range 6-52) mo. The high rate of healing (85.2%) in our study after 8 wk of treatment is possibly related to the long duration of treatment, considering that the usual treatment for acute anal fissure ranges between 3 and 4 wk. This high healing rate may be attributed not only to the reduction of the anal canal pressure (significant in our patients) through the inhibition of the flow of calcium into the sarcoplasm of the internal anal sphincter, but also to the anti-inflammatory action of nifedipine. Experimental studies indicate that nifedipine has a modulating effect on the microcirculation[23] and a local anti-inflammatory effect[24], in addition to relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. From a further viewpoint, laser Doppler flowmetry has shown that the posterior area of the anoderm is less well perfused than other areas of the anoderm. It has been speculated that increased tone in the internal sphincter muscle further reduces the blood flow, especially at the posterior midline. Based on these findings, fissures are thought to represent ischemic ulceration[25]. Since oxidative stress is believed to initiate and aggravate many diseases including peptic-ischemic ulcerations[26,27], it could be speculated that nifedipine might promote acute fissure healing rate because of its additional free radical-scavenging properties as well as its cytoprotective and peptic ulcer healing-promoting actions[28]. However, further studies are needed to elucidate these potential therapeutic properties of this drug in healing acute as well as chronic anal fissures.

A high fiber diet by itself or in addition to topical ointments consists of a part of acute anal fissure treatment. Since our study included patients with acute anal fissures, which did not respond to conservative therapy consisting of stool softeners, high fiber diet and topical anesthetic cream, it is impossible to attribute the success of treatment to high fiber diet which we encouraged the patients to continue.

It should be emphasized that the two unhealed patients after 8 wk of treatment and all recurrences during the follow-up were successfully treated with an additional 4-wk course of topical 0.5% nifedipine ointment. The main limitation of this study is the lack of a placebo group. Although CCBs have not been directly compared in any analysis with an arm termed as placebo, there are 2 studies comparing nifedipine with either hydrocortisone[13] or lidocaine[12]. A marked advantage of nifedipine over substances currently thought to be the equivalent of placebo has been reported, with a healing rate of approximately 35% in the placebo groups[13]. Our study has shown a healing rate of 85.2%, significantly higher than the previously reported rate in placebo groups (35%).

Another drawback in our study suggests that treatment of acute anal fissure with 0.5% nifedipine ointment is the length of treatment (8 wk), which is generally considered to be longer than the typical length (usually 3-4 wk). Although this extended length of treatment may increase the percentage of non-compliant patients, only 3 out of the 31 patients (10%) did not complete the 8-wk treatment in our study. This non-compliance percentage is comparable to that of other studies[7,8,12,13].

An interesting finding of our study is the fact that, despite the applied dosage of nifedipine (0.5%) was at least twice as high as in previous studies[12,13], there was no increase in adverse effects. Only two patients (7.4%) presented with moderate headache, which was relieved with paracetamol.

In conclusion, topical application of 0.5% nifedipine ointment might be effective both in treating acute anal fissure and in preventing its evolution to chronicity.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Jonas M, Scholefield JH. Anal Fissure. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:167-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ. Relationship between anal pressure and anodermal blood flow. The vascular pathogenesis of anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:664-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khubchandani IT, Reed JF. Sequelae of internal sphincterotomy for chronic fissure in ano. Br J Surg. 1989;76:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pernikoff BJ, Eisenstat TE, Rubin RJ, Oliver GC, Salvati EP. Reappraisal of partial lateral internal sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1291-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dorfman G, Levitt M, Platell C. Treatment of chronic anal fissure with topical glyceryl trinitrate. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1007-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kennedy ML, Sowter S, Nguyen H, Lubowski DZ. Glyceryl trinitrate ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a placebo-controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1000-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carapeti EA, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Topical diltiazem and bethanechol decrease anal sphincter pressure and heal anal fissures without side effects. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1359-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Knight JS, Birks M, Farouk R. Topical diltiazem ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 2001;88:553-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Maria G, Cassetta E, Gui D, Brisinda G, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A. A comparison of botulinum toxin and saline for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mínguez M, Melo F, Espí A, García-Granero E, Mora F, Lledó S, Benages A. Therapeutic effects of different doses of botulinum toxin in chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1016-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pitt J, Dawson PM, Hallan RI, Boulos PB. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of oral indoramin to treat chronic anal fissure. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Antropoli C, Perrotti P, Rubino M, Martino A, De Stefano G, Migliore G, Antropoli M, Piazza P. Nifedipine for local use in conservative treatment of anal fissures: preliminary results of a multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Perrotti P, Bove A, Antropoli C, Molino D, Antropoli M, Balzano A, De Stefano G, Attena F. Topical nifedipine with lidocaine ointment vs. active control for treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1468-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ho KS, Ho YH. Randomized clinical trial comparing oral nifedipine with lateral anal sphincterotomy and tailored sphincterotomy in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 2005;92:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chrysos E, Xynos E, Tzovaras G, Zoras OJ, Tsiaoussis J, Vassilakis SJ. Effect of nifedipine on rectoanal motility. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:212-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ağaoğlu N, Cengiz S, Arslan MK, Türkyilmaz S. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dig Surg. 2003;20:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cook TA, Brading AF, Mortensen NJ. Differences in contractile properties of anorectal smooth muscle and the effects of calcium channel blockade. Br J Surg. 1999;86:70-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cook TA, Brading AF, Mortensen NJ. Effects of nifedipine on anorectal smooth muscle in vitro. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:782-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jonard P, Essamri B. Diltiazem and internal anal sphincter. Lancet. 1987;1:754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jonas M, Neal KR, Abercrombie JF, Scholefield JH. A randomized trial of oral vs. topical diltiazem for chronic anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1074-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Katsinelos P, Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I, Paroutoglou G, Dimiropoulos S, Souparis A, Atmatzidis K. Topical 0.5% nifedipine vs. lateral internal sphincterotomy for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: long-term follow-up. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ezri T, Susmallian S. Topical nifedipine vs. topical glyceryl trinitrate for treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:805-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oshiro H, Kobayashi I, Kim D, Takenaka H, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. L-type calcium channel blockers modulate the microvascular hyperpermeability induced by platelet-activating factor in vivo. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:732-739; discussion 732-739;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fleischmann JD, Huntley HN, Shingleton WB, Wentworth DB. Clinical and immunological response to nifedipine for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1991;146:1235-1239. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Tracy H. Examination and diseases of the anorectum. Philadelphia: Saunders 2002; 2277-2293. |

| 26. | Brzozowski T, Konturek PC, Konturek SJ, Drozdowicz D, Kwiecieñ S, Pajdo R, Bielanski W, Hahn EG. Role of gastric acid secretion in progression of acute gastric erosions induced by ischemia-reperfusion into gastric ulcers. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tandon R, Khanna HD, Dorababu M, Goel RK. Oxidative stress and antioxidants status in peptic ulcer and gastric carcinoma. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48:115-118. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Suzuki Y, Ishihara M, Segami T, Ito M. Anti-ulcer effects of antioxidants, quercetin, alpha-tocopherol, nifedipine and tetracycline in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;78:435-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |