Published online Oct 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6098

Revised: January 28, 2006

Accepted: February 28, 2006

Published online: October 14, 2006

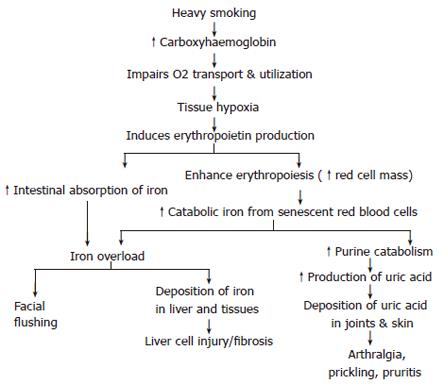

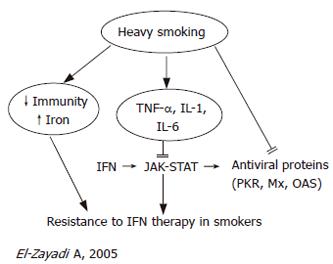

Smoking causes a variety of adverse effects on organs that have no direct contact with the smoke itself such as the liver. It induces three major adverse effects on the liver: direct or indirect toxic effects, immunological effects and oncogenic effects. Smoking yields chemical substances with cytotoxic potential which increase necroinflammation and fibrosis. In addition, smoking increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α) that would be involved in liver cell injury. It contributes to the development of secondary polycythemia and in turn to increased red cell mass and turnover which might be a contributing factor to secondary iron overload disease promoting oxidative stress of hepatocytes. Increased red cell mass and turnover are associated with increased purine catabolism which promotes excessive production of uric acid. Smoking affects both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses by blocking lymphocyte proliferation and inducing apoptosis of lymphocytes. Smoking also increases serum and hepatic iron which induce oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation that lead to activation of stellate cells and development of fibrosis. Smoking yields chemicals with oncogenic potential that increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with viral hepatitis and are independent of viral infection as well. Tobacco smoking has been associated with supression of p53 (tumour suppressor gene). In addition, smoking causes suppression of T-cell responses and is associated with decreased surveillance for tumour cells. Moreover, it has been reported that heavy smoking affects the sustained virological response to interferon (IFN) therapy in hepatitis C patients which can be improved by repeated phlebotomy. Smoker’ssyndrome is a clinico-pathological condition where patients complain of episodes of facial flushing, warmth of the palms and soles of feet, throbbing headache, fullness in the head, dizziness, lethargy, prickling sensation, pruritus and arthralgia.

- Citation: El-Zayadi AR. Heavy smoking and liver. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(38): 6098-6101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i38/6098.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6098

Lighting a cigarette creates over 4000 harmful chemicals with hazardous adverse effects on almost every organ in the body. The impact of heavy smoking on the pathogenesis of liver disease and response to interferon therapy among chronic hepatitis patients has been overlooked. Before we begin this article; it is necessary to define who is a heavy smoker and to shed light on the common toxic constituents of cigarette smoking.

Heavy smokers are variably defined, some studies suggest exposure to two or more packets (≥ 40 cigarettes) a day for 10 years or more[1]. On the other hand, Marrero et al[2] have defined heavy smokers as those exposed to greater than 20 pack-years.

The constituents of smoke are contained in either the particulate phase or gas phase.

Particulate phase components include tar, polynuclear hydrocarbons, phynol, cresol, catechol and trace elements (carcinogens), nicotine (ganglion stimulator and depressor), indole, carbazole (tumor accelerators)[3], and 4-aminobiphenyl[4].

Gas phase contains carbon monoxide (impairs oxygen transport and utilization), hydrocyanic acid, acetaldehyde, acrolein, ammonia, formaldehyde and oxides of nitrogen (cilitoxin and irritant) nitrosamines, hydrazine and vinyl chloride (carcinogens)[3].

Smokers are at greater risk for cardiovascular diseases (ischaemic heart disease, hypertension), respiratory disorders (bronchitis, emphysema, chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma), cancer (lung, pancreas, breast, liver, bladder, oral, larynx, oesophagus, stomach and kidney), peptic ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), male impotence and infertility, blindness, hearing loss, bone matrix loss, and hepatotoxicity[5,6].

Beside the hazardous effects mentioned before; smoking causes a variety of adverse effects on organs that have no direct contact with the smoke itself such as liver. The liver is an important organ that has many tasks. Among other things, the liver is responsible for processing drugs, alcohol and other toxins to remove them from the body. Heavy smoking yields toxins which induce necroinflammation and increase the severity of hepatic lesions (fibrosis and activity scores) when associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV)[7] or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[8]. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of developing HCC among chronic liver disease (CLD) patients[9] independently of liver status. Association of smoking with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) irrespective of HBV status has been reported[10,11].

Smoking induces three major adverse effects on the liver: toxic effects either direct or indirect, immunological effects and oncogenic effects.

Direct toxic effect: Smoking yields chemical substances with cytotoxic potentials[12]. These chemicals created by smoking induce oxidative stress associated with lipid peroxidation[13,14] which leads to activation of stellate cells and development of fibrosis. In addition, smoking increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α) involved in liver cell injury[15]. It has been reported that smoking increases fibrosis score and histological activity index in chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients[7] and contributes to progression of HBV-related cirrhosis[8].

Heavy smoking is associated with increased carboxyhaemoglobin and decreased oxygen carrying capacity of red blood cells (RBCs) leading to tissue hypoxia. Hypoxia stimulates erythropoetien production which induces hyperplasia of the bone marrow. The latter contributes to the development of secondary polycythemia and in turn to increased red cell mass and turnover. This increases catabolic iron derived from both senescent red blood cells and iron derived from increased destruction of red cells associated with polycythemia[16,17]. Furthermore, erythropoietin stimulates absorption of iron from the intestine. Both excess catabolic iron and increased iron absorption ultimately lead to its accumulation in macrophages and subsequently in hepatocytes over time, promoting oxidative stress of hepatocytes[18]. Accordingly, smoking might be a contributing factor to secondary iron overload disease in addition to other factors such as transfusional haemosidrosis, alcoholic cirrhosis, thalassemia, sideroplastic anemia and porphyria cutanea tarda.

In the meantime, increased red cell mass and turnover are associated with increased purine catabolism which promotes excessive production of uric acid. Eventually uric acid is deposited in tissues and joints as manifested clinically by prickling sensation, pruritus and arthralgia[19] (Figure 1).

Smoker’s syndrome: Smoker’s syndrome is a clinico-pathological condition reported in patients smoking ≥40 cigarettes or 10 stones of popular shisha (water-pipe) in Egypt per day, over a long time. These patients suffer from episodes of facial flushing, warmth of the palms and soles, throbbing headache, fullness in the head, dizziness, lethargy, prickling sensation, pruritus and arthralgia[20]. However, the majority of patients who smoke less than the described level are subject to biochemical changes rather than clinical manifestations.

Facial flushing, the most prominent symptom, is explained by capillary vasodilatation associated with increased blood flow through the skin. The vasodilatation may be attributed to the direct action of vasodilator constituents of the smoke as well as to excess haemoglobin saturation[21] reported among heavy smokers[20].

On examination of these smokers, the face appears dusky-red and/or pigmented, the pulse is full. The smokers suffer from hypertension, joint stiffness and swelling. Some of them have experienced cerebrovascular and cardiovascular strokes. Laboratory studies have revealed an increased Hb level (> 160 g/L) and haematocrit (> 55 mL/100 mL) in almost all the patients and raised ALT (> 2 fold), uric acid (> 6 mg/dL), serum iron (> 165 μg/dL) and ferritin in most of the patients. Histopathological examination reveals hepatic necro-inflammation, apoptotic necrosis, fibrosis, and deposition of iron in hepatocytes as demonstrated by Perl’s stain.

Smoking affects both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses[22]. Nicotine blocks lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation including suppression of antibody-forming cells[15,23] by inhibiting antigen-mediated signaling in T-cells[15,23,24] and riboneucleotide reductase[25]. Furthermore, smoking induces apoptosis of lymphocytes[26] by enhancing expression of Fas (CD95) death receptor which allows them to be killed by other cells expressing a surface protein called Fas ligand (FasL). Smoking induces elevation of CD8+ T-cytotoxic lymphocytes[14], decreased CD4+ cells, impaired NK cell activity[27] and increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α)[15].

Although smoking has long-term adverse effects; cessation of smoking reversed these effects, such as elevation of NK activity which is detectable within one month of smoking cessation[28], elevation of both antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses as well as decreased proinflammatory cytokines and increased antioxidant activity.

Smoking yields chemicals with oncogenic potentials such as hydrocarbons, nitrosamine, tar and vinyl chloride[29]. Cigarette smoking is a major source of 4-aminobiphenyl, a hepatic carcinogen which has been implicated as a causal risk factor for HCC[4]. Smoking increases the risk of HCC in patients with viral hepatitis[9,30,31]. Furthermore, recent data from China and Taiwan have shown an association of smoking with liver cancer independent of HBV status[10,11]. Tobacco smoking is associated with reduction of p53, a tumour suppressor gene[32,33] which is considered “the genome guardian”. Suppression of T-cell responses by nicotine and tar is associated with decreased surveillance for tumour cells[25]. El-Zayadi et al[20] reported that heavy smokers accumulate excess iron in hepatocytes which induces fibrosis and favours development of HCC. Smoking is considered a co-factor with HBV and HCV for hepatocarcinogenesis[31]. In addition, suppressed mood, a common feature among heavy smokers, increases the risk for development of cancer[25].

El-Zayadi et al[20] have reported an association between heavy smoking and liver cell injury in the form of necroinflammation, apoptosis and excess iron deposition in the liver. These effects are attributed to iron overload with consequent iron deposition in hepatocytes[20,34]. Excess hepatic iron induces oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation[13,14]. However, iron overload will not correct itself and the only exit of iron from the body is by bleeding or frequent chelation[35]. Therapeutic phlebotomy allows excess iron to be removed from the body and chelation of labile iron from the liver.

El-Zayadi et al[36] reported that smokers suffering from chronic hepatitis C tend to have a lower response rate to IFN therapy. Therapeutic phlebotomy among chronic hepatitis C patients improves the response rate to IFN therapy[37,38]. Furthermore, the authors recommended that chronic hepatitis C patients should be advised to avert smoking before embarking on IFN therapy[36].

Several mechanisms have been implemented in resistance to IFN therapy in heavy smokers which are summarized in Figure 2. First, heavy smoking causes immunosuppression[22] such as reduction in CD4+ cells, impaired NK cytotoxic activity[27] and recognition of virus-infected cells, and induces apoptosis of lymphocytes[26]. Second, heavy smoking increases hepatic iron overload which is involved in resistance to IFN[20]. Third, smoking induces pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α)[15] that mediate necroinflammation and steatosis. Fourth, smoking directly modifies IFN-α-activated cell signaling and action[39].

The present article sends a message indicating that smoking is an underestimated risk factor for liver disease. In this respect, further well-designed studies are needed to clarify this issue.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD. Perceived risks of heart disease and cancer among cigarette smokers. JAMA. 1999;281:1019-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Fu S, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2005;42:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Burns DM. Cigarettes and cigarette smoking. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12:631-642. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wang LY, Chen CJ, Zhang YJ, Tsai WY, Lee PH, Feitelson MA, Lee CS, Santella RM. 4-Aminobiphenyl DNA damage in liver tissue of hepatocellular carcinoma patients and controls. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McBride PE. The health consequences of smoking. Cardiovascular diseases. Med Clin North Am. 1992;76:333-353. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sherman CB. Health effects of cigarette smoking. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12:643-658. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Njapoum C, Duchatelle V, Degott C, Erlinger S, Rueff B, Valla DC, Degos F. Cigarette smoking and hepatic lesions in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;34:121-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yu MW, Hsu FC, Sheen IS, Chu CM, Lin DY, Chen CJ, Liaw YF. Prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:1039-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mukaiya M, Nishi M, Miyake H, Hirata K. Chronic liver diseases for the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in Japan. Etiologic association of alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and the development of chronic liver diseases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:2328-2332. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wang LY, You SL, Lu SN, Ho HC, Wu MH, Sun CA, Yang HI, Chien-Jen C. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and habits of alcohol drinking, betel quid chewing and cigarette smoking: a cohort of 2416 HBsAg-seropositive and 9421 HBsAg-seronegative male residents in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen ZM, Liu BQ, Boreham J, Wu YP, Chen JS, Peto R. Smoking and liver cancer in China: case-control comparison of 36,000 liver cancer deaths vs. 17,000 cirrhosis deaths. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yuen ST, Gogo AR Jr, Luk IS, Cho CH, Ho JC, Loh TT. The effect of nicotine and its interaction with carbon tetrachloride in the rat liver. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;77:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Husain K, Scott BR, Reddy SK, Somani SM. Chronic ethanol and nicotine interaction on rat tissue antioxidant defense system. Alcohol. 2001;25:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Watanabe K, Eto K, Furuno K, Mori T, Kawasaki H, Gomita Y. Effect of cigarette smoke on lipid peroxidation and liver function tests in rats. Acta Med Okayama. 1995;49:271-274. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Moszczyński P, Zabiński Z, Moszczyński P, Rutowski J, Słowiński S, Tabarowski Z. Immunological findings in cigarette smokers. Toxicol Lett. 2001;118:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Young CJ, Moss J. Smoke inhalation: diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Anesth. 1989;1:377-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heimbach DM, Waeckerle JF. Inhalation injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1316-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Iron toxicity and oxygen radicals. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1989;2:195-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nakanishi N, Yoshida H, Nakamura K, Suzuki K, Tatara K. Predictors for development of hyperuricemia: an 8-year longitudinal study in middle-aged Japanese men. Metabolism. 2001;50:621-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Zayadi AR, Selim O, Hamdy H, El-Tawil A, Moustafa H. Heavy cigarette smoking induces hypoxic polycythemia (erythrocytosis) and hyperuricemia in chronic hepatitis C patients with reversal of clinical symptoms and laboratory parameters with therapeutic phlebotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1264-1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cutaneous manifestations of disorders of the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems. In: Freedberg IM, eds. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine, 5th ed., volume 2. New York: McGraw-Hill 1999; 2064. |

| 22. | Sopori ML, Kozak W. Immunomodulatory effects of cigarette smoke. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Geng Y, Savage SM, Razani-Boroujerdi S, Sopori ML. Effects of nicotine on the immune response. II. Chronic nicotine treatment induces T cell anergy. J Immunol. 1996;156:2384-2390. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Goud N; Immunotoxicology and immunopharmocology. 2nd ed. New Yourk: Raven Press. . |

| 25. | McCue JM, Link KL, Eaton SS, Freed BM. Exposure to cigarette tar inhibits ribonucleotide reductase and blocks lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 2000;165:6771-6775. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Suzuki N, Wakisaka S, Takeba Y, Mihara S, Sakane T. Effects of cigarette smoking on Fas/Fas ligand expression of human lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1999;192:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zeidel A, Beilin B, Yardeni I, Mayburd E, Smirnov G, Bessler H. Immune response in asymptomatic smokers. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:959-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Meliska CJ, Stunkard ME, Gilbert DG, Jensen RA, Martinko JM. Immune function in cigarette smokers who quit smoking for 31 days. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:901-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Helen A, Vijayammal PL. Vitamin C supplementation on hepatic oxidative stress induced by cigarette smoke. J Appl Toxicol. 1997;17:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yu MW, Chiu YH, Yang SY, Santella RM, Chern HD, Liaw YF, Chen CJ. Cytochrome P450 1A1 genetic polymorphisms and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:598-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Alberti A, Chemello L, Benvegnù L. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang B, Zhang Y, Xu DZ, Wang AH, Zhang L, Sun CS, Li LS. [Meta-analysis on the relationship between tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and p53 alteration in cases with esophageal carcinoma]. Zhonghua Liuxing Bingxue Zazhi. 2004;25:775-778. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Yu MW, Yang SY, Chiu YH, Chiang YC, Liaw YF, Chen CJ. A p53 genetic polymorphism as a modulator of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in relation to chronic liver disease, familial tendency, and cigarette smoking in hepatitis B carriers. Hepatology. 1999;29:697-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bonkovsky HL, Banner BF, Rothman AL. Iron and chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 1997;25:759-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Porter JB. Monitoring and treatment of iron overload: state of the art and new approaches. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:S14-S18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | El-Zayadi A, Selim O, Hamdy H, El-Tawil A, Badran HM, Attia M, Saeed A. Impact of cigarette smoking on response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C Egyptian patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2963-2966. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Fontana RJ, Israel J, LeClair P, Banner BF, Tortorelli K, Grace N, Levine RA, Fiarman G, Thiim M, Tavill AS. Iron reduction before and during interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2000;31:730-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fargion S, Fracanzani AL, Rossini A, Borzio M, Riggio O, Belloni G, Bissoli F, Ceriani R, Ballarè M, Massari M. Iron reduction and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: results of an Italian multicenter randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1204-1210. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |