DISCUSSION

Cystadenomas are rare, benign but potentially malignant, multilocular, cystic neoplasms of the biliary ductal system[1,2,7,10], accounting for less than 5% of cystic neoplasms of the liver[5,6,10]. The incidence of intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas is between one in 20 000 to one in 100 000 people while the incidence of cystadenocarcinomas approximately one per 10 million patients[14]. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas can occur at any age[15], but they are usually seen in middle-aged women[7,10,11,16]. Approximately 85%-95% of the patients are women[12,15,17]. Even though they are true proliferative epithelial tumors, their progression is characteristically slow and years are required before they enlarge[11]. Their size is variable ranging from 1.5 to 30 cm in diameter[2,5,11,16,18]. They usually arise in liver (80%-85%)[2,3,7,10,19,20], less frequently in extrahepatic bile ducts[2,3,7,10,17,19] and rarely in gallbladder[4]. Approximately 50%-55% of cystadenomas are located in the right lobe with the remaining located in the left lobe or in both lobes (30%-40% in the left lobe and about 15%-20% in both lobes) while few arise from extrahepatic ducts[2,11,12,21]. Accordingly, the common or the right bile duct can be identified as the origin in more than half of cases.

Although reports of cystadenomas have been increasing due to advances in imaging diagnoses and the common use of US and CT, less than 100 reports of intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas are identified in the literature[5,7-10,22] and only 26 extrahepatic cystadenomas have been reported[17,23]. A review of the literature is provided along with a discussion addressing the clinical presentation, histology, histogenesis, differential diagnosis, imaging features, treatment and prognosis for this rare entity.

Clinical presentation

The patients may be asymptomatic with their tumor discovered incidentally during radiographic evaluation or surgical exploration for other clinical indications or even at autopsy[6,24]. However, they often have vague abdominal complaints related to extrinsic compression of adjacent structures such as the stomach, duodenum, or biliary tree. Symptomatic patients present with an insidious onset of symptoms due to the slowly growing nature of the neoplasm[12].

The typical patient is a white female presenting with abdominal discomfort, swelling, gradual increase in abdominal girth and/or pain and a palpable abdominal mass[5,7,11,12]. Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain along with increasing abdominal girth or awareness of an abdominal mass are the main complaints in about 60% of the patients as reviews of the reported cases have shown[21]. In another series, complaints include abdominal pain in 74%, abdominal distension in 26%, and nausea/vomiting in 11% of the patients[25]. The patients may less frequently have gastrointestinal obstruction leading to nausea and vomiting, dyspepsia, anorexia, weight loss or ascites[11,26].

When complicated, symptoms include biliary obstruction[5,7,12], rupture[19], bacterial infection[19], intracystic hemorrhage[19,22] or malignant transformation[7,10]. Biliary obstruction may be either due to the tumor itself[21,27] or either, rarely, due to the secretion of mucin[20,28] and is manifested as jaundice, biliary colic, cholangitis, nausea, fever, chills, itching, or steatorrhea[22]. Such cases represent approximately 35% of the patients with cystadenomas[24]. Patients may experience intermittent jaundice or repetitive episodes of biliary colic or cholangitis for a long period of time before the diagnosis[21,22]. Obstructive jaundice, although not always present[29], is the most frequent presenting symptom in patients with extrahepatic cystadenomas[17,19]. Other reported symptoms are right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, skin itching and occasional diarrhea[29]. On the contrary, in intrahepatic cystadenomas, biliary obstruction is rarely the chief presenting complaint of the patients[22]. Any patient with clinical or biochemical obstructive jaundice of unknown etiology or recurrence of a liver cyst following surgical treatment should be suspected of having an intrahepatic or extrahepatic cystadenoma[28-30] or a cystadenocarcinoma[5,10].

Histology

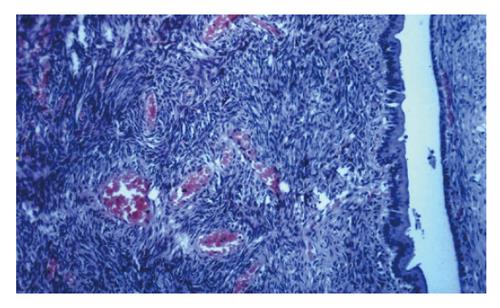

Biliary cystadenomas are usually large, multiloculated, with internal septation and nodularity and surrounded by a dense cellular fibrostroma. Although it may be extremely rarely be unilocular[18,22], multilocularity of the tumor is a key feature that distinguishes cystadenomas from developmental cysts[16]. Biliary cystadenomas are usually globular, with a smooth external surface and a smooth or trabeculated inner surface and contain locules of variable sizes[10,16]. The internal surface of the cyst may also have papillary infoldings or smaller cysts[10]. On light microscopy, cystadenoma consists of three layers: a cyst lining of biliary-type epithelium, a moderately-to-densely cellular stroma, and a dense layer of collagenous connective tissue[31].

The cyst wall consists of a single layer which is typical of biliary-type epithelium containing cuboidal-to-tall columnar and nonciliated mucin secreting epithelial cells with papillary progressions, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and basally oriented nuclei. The cyst usually contains clear mucinous fluid[10,19] which raises the possibility of a malignant component when hemorrhage occurs[4,11], unless there is a trauma history. Rarely, the fluid within the cyst may be bilious, purulent, proteinaceous, gelatinous, clear or mixed. The septa of the tumor may show calcification.

Foci of epithelial atypia or dysplasia consisting of nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia, multilayer, loss of polarity, and mitotic activity indicate potential malignant changes[7,16]. Anaplasia or pleomorphism, severe architectural atypia (such as exophytic papillae) and capsular or stromal invasion are features of malignancy[5,10,16]. The premalignant progression is usually based on the histologic presence of intestinal metaplasia which is characterized by the presence of numerous goblet cells[7]. Careful pathologic evaluation is emphasized since malignant degeneration or transformation can be detected only after thorough sectioning. Histological differentiation of biliary cystadenoma from other cystic liver lesions is usually based on its multilocularity, columnar epithelium, papillary infoldings, and ovarian-like stroma[16].

Similar lesions occur in the pancreas and ovary. Two histological variants of biliary cystadenoma are recognized, a serous type and a far more common mucinous type[16]. The rare serous variety resembles serous cystadenoma of the pancreas and is not known to undergo malignant transformation[16]. The mucinous type is predominantly a tumor of middle-aged women and is similar to mucinous cystadenoma of the pancreas[16].

If the underlying subepithelial stroma is densely cellular resembling ovarian stroma as in our case, it is referred as “mesenchymal stroma”[5,8]. The stromal cells are spindle-shaped and usually immunoreactive with vimentin, alpha-smooth muscle actin, and muscle-specific actin and less frequently with desmin, estrogen and progesterone receptors[8,16,27]. Although mesenchyme of these tumors resembles ovarian stroma morphologically, such immunohistochemical features are characteristic of myofibroblasts[8,31]. Mesenchymal stroma is more often observed in the mucinous type of cystadenoma[16]. There are two distinct types of cystadenomas based on the presence or absence of “mesenchymal stroma”[5]. Cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma occurs exclusively in women[5,7,8,31,32] while cystadenoma without mesenchymal but with hyaline stroma arises in both men and women and tends to occur in older patients[5,32]. Cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma is regarded as a precancerous lesion[33] but the type without mesenchymal stroma seems to undergo malignant degeneration much more frequently[32]. Patients with cystadenocarcinoma with mesenchymal stroma have a good prognosis whereas the prognosis of patients with cystadenocarcinoma without mesenchymal stroma is poor, especially in men[7]. The malignancy arises from the epithelial component in most cases[33], although sarcomatous transformation of the mesenchymal stroma has been reported[31,34].

Etiology-histogenesis

The origin of biliary cystadenomas is unclear. Theories on their etiology and histogenesis are not solid since both acquired and congenital origins have been proposed. Experimental studies by Cruickshank et al[34] may support the theory of an acquired lesion. The development of the tumor as a reactive process to some focal injury has also been mentioned[10]. Mesenchymal stroma, though resembling ovarian microscopically, is more akin to the primitive mesenchyme in embryonic gallbladder and large bile ducts[8,9], suggesting that the tumor may arise from ectopic embryonal tissue destined to form the gallbladder[9] or from ectopic embryonic rests of primitive foregut sequestered within the liver[5,10,33]. Demonstration of endocrine cells in about 50% of hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas could also suggest an origin from intrahepatic peribiliary glands[35]. The presence of hamartomatous structures and development abnormalities supports the theory of congenital origin in at least some cystadenomas[10,36].

A possible hormonal dependance of cystadenomas with mesenchymal stroma has also been proposed since immunohistochemical studies showing the characteristics of mesenchymal stromal cells, have revealed myofibroblastic phenotype and expression of progesterone and estrogen receptors[27,37,38]. In addition, there are reports of this tumor occurring in oral contraceptive users, suggesting that estrogen-containing oral contraceptives may serve as tumor promoters[11,38]. Ectopic ovarian tissue, however, is considered an unlikely origin of these tumors[5,8].

It is uncertain whether biliary cystadenocarcinomas are de-novo cancer or are derived from cystadenomas. They are generally thought, however, to arise from preexisting benign cystadenomas since many cystadenocarcinomas contain areas of cystadenoma in the same sample[5,10,33,39].

Differential diagnosis

In the evaluation of cystic hepatic lesions, a high index of suspicion is imperative. Moreover, since these neoplasms have a strong tendency to recur and undergo malignant transformation, differentiating between cystadenomas and other cystic liver lesions is substantially important. Differential diagnosis includes simple liver cysts, parasitic cysts (particularly hydatid cysts), haematomas or post-traumatic cysts, liver abscesses, congenital cysts, polycystic disease, hamartomas, Caroli’s disease, and neoplasmatic lesions such as biliary cystadenocarcinoma, undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma, cystic metastasis, metastatic pancreatic or ovarian cystadenocarcinoma, biliary papilloma, cystic primary hepatocellular carcinoma, cystic cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatobiliary mesenchymal tumors (particularly biliary smooth muscle neoplasms) such as biliary leiomyoma, adenomyoma, and primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma[2,27,40]. Preoperative and intraoperative diagnosis of biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas can be very difficult and differentiation between these two entities can be safely done only after histopathologic evaluation[1,5,6,10,33,40].

Specific attention should be paid to liver hydatid disease, especially in countries with a high incidence of the disease. Since its imaging features are similar to those of cystadenoma as in our patient, preoperative differentiation may be impossible without serologic tests[2,24,41]. Anti-echinococcus granulosis and anti-amoebic serologic tests, estimation of CA 19-9, CEA and AFP levels, general evaluation of liver and renal function as well as abdominal US, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed. Liver function tests may be normal or elevated in cases of intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct compression[11,27,29].

Although they do not rule out cystadenoma when normal[14], serum Ca 19-9 levels are believed to be a valuable marker in the diagnosis and monitoring in the postoperative follow-up since they are reported to return to normal after complete resection[11,42]. Nevertheless, immunoreactivity for CA 19-9 is lost therefore minimizing the possible benefit of serial follow-up when cystadenoma is transformed to cystadenocarcinoma[43].

Measurement of cyst fluid CA 19-9 and CEA levels has been advocated as an adjunctive preoperative procedure for enhancing the accuracy of differentiation of cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas from other hepatic lesions[14,44]. High levels of CA 19-9 and CEA can be encountered in cystic fluid or in epithelial lining of biliary cystadenomas, particularly in those with mesenchymal stroma[5,14,30,41,44] and cystadenocarcinomas[45]. These elevated cyst fluid tumor markers clearly indicate the neoplastic features and biliary origin of these cysts[5]. Elevation of CEA may, however, be moderate or not always present[14]. On the contrary, substantially higher levels of CA 19-9 in cystic fluid are observed in the majority of cystadenomas compared with those in simple cysts, echinococcal cysts, and polycystic liver disease[14,30,41,42,44]. Therefore, though not allowing differentiation between cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma, measurement of CA 19-9 in cystic fluid obtained by fine needle aspiration as well as in serum may be helpful in the differential diagnosis of hepatic cystic lesions. Moreover, Koffron et al[14] have proposed a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for hepatic cysts and particularly intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas based on CA 19-9 and CEA levels and cytology along with laparoscopic cyst wall biopsy.

Percutaneous fine needle aspiration also provides fluid for bilirubin concentration analysis, which is suggestive of communication of cystadenoma with the biliary tract when it is elevated[14], and for cytologic evaluation which may be helpful in excluding hepatic abscess, cystic metastases and other cystic lesions. Although there are reports of cystadenocarcinomas arising from cystadenomas diagnosed by percutaneous fine needle aspiration cytology[45,46], it is not very accurate since this procedure relying on adequate sampling may miss the microscopic foci of the carcinoma in cystadenoma[44,47,48]. Thus, correlation of aspiration cytology with clinical and radiological data has been suggested[14,47]. Fine needle aspiration and needle biopsy for diagnosis, however, may also risk dissemination of tumor cells and is not generally recommended, particularly when surgery is planned[30,48]. Pleural and peritoneal dissemination of tumor cells caused by aspiration has been reported[48,49].

Furthermore, examination of epithelial cells of several types of hepatic cysts by mucin histochemistry and immunohistochemistry reveals different features of these cells regarding mucus and antigenic expression among the hepatic cysts[50]. Epithelial cells of non-parasitic simple cysts and adult-type polycystic liver show similar mucin-histochemical and immunohistochemical features, and are characterized by little mucin and weak immunoreactivities to several antibodies. On the contrary, epithelial cells of cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are characterized by much mucin and moderate to strong immunoreactivities to cytokeratins CAM5.2 and AE1 and AE3 as well as to CA 19-9, CEA and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)[16,50].

Although frozen sections may be helpful in differenti-ation of cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas from other cystic hepatic lesions[18], they are not very useful due to the variability in histology of cystadenomas and their inability to rule out cystadenocarcinomas[48,51,52]. Careful histopathologic evaluation of the resected specimen, therefore, constitutes the only safe diagnostic modality of hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas while malignant degeneration or transformation of a cystadenoma can only be detected after thorough sectioning.

Imaging features

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of cystadenoma from other cystic hepatic lesions are mainly based on abdominal US, CT scan and MRI. Preoperative US assessment is almost always performed but cannot replace the diagnostic value of CT. Moreover, the role of US and CT is considered complementary[53]. By US the tumor appears well-demarcated, thick-walled, noncalcified, anechoic or hypoechoic, globular or ovoid, cystic mass and may present thin internal septations, which are highly echogenic, mural nodules and polypoid or papillary infoldings[2,11,15,24,53]. Dilatation of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts may also be disclosed[27]. In case of intracystic hemorrhage, US may show a hyperechoic mass with no septation[22].

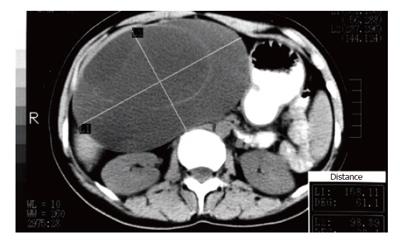

The need to determine the size, morphology and anatomic relation to surrounding structures, particularly major vessels of the lesion prior to intervention is crucial and CT is of great help for the surgeon. Additionally, CT during arteriography is useful to demonstrate the tumor vascularity[45]. Common features on CT scan include low-density, well-defined, lobulated, multilocular, thick-walled, cystic masses with internal septa and occasionally mural nodules[2,12,15,26,53]. Intravenous contrast on CT enhances the cyst wall and septations. CT may sometimes demonstrate dilatation of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts. Rarely capsular, mural or septal calcification presents on US or CT[2,15,54]. Although such features can be identified with CT and are essential for differentiating cystadenoma from other cystic liver lesions, a possible preoperative diagnosis is rarely suspected due to the rarity of the disease.

Demonstration of communication between the tumor and the biliary tract is of important diagnostic value both in identifying the site of origin of the tumor and in differentiating biliary cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma from other hepatic cystic lesions[54]. Such a communication can be demonstrated with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or cystography (PTC), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), intrao-perative cholangiography, cyst fluid examination for bile content, or surgical exploration[12,14,18,45,54,55]. Moreover, since the potential for cystadenomas to extend intraluminally into extrahepatic ducts has been described[41], preoperative extrahepatic biliary imaging is imperative when surgical management is planned. It is noteworthy that no biliary connection has been identified, even at the time of surgery, in the majority of reported cystadenomas[11]. In a review of the literature, Sato et al[45] reported that such a biliary fistula was found in only 21 cystadenomas and 16 cystadenocarcinomas.

ERCP or PTC may show an intraluminal filling defect that may be the tumor or represent intraluminal mucin[20]. An infrequent finding is the endoscopic visualization of mucin being extruded through the ampulla of Vater[18]. PTC can provide further information on biochemical and cytologic examinations of the cyst fluid[45]. However, fine needle aspiration cytology is not very accurate[44,47,48] while aspiration may risk possible tumor pleural or peritoneal seeding[48,49]. Therefore, it should be avoided in cases of obvious or suspected cystadenocarcinoma, especially when surgery is planned[48]. ERCP may also be performed in order to reveal or exclude compression or displacement of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and is especially important if patients present with jaundice[19]. Furthermore, diagnosis of a cystadenoma of the extrahepatic biliary tree can be obtained by intraoperative cholangiography and/or choledochoscopy, PTC, ERCP, MRCP or spiral CT scan[21,55-57].

MRI is a valuable tool for the diagnosis and differentiation of cystadenoma from other cystic liver lesions while combination of MRI with MRCP is also even more useful[55]. On T1-weighted images, MRI reveals a fluid-containing, multilocular, septated mass with homogenous low signal intensity, the wall and septa of which become enhanced after administration of Gd-DTPA[2,54,55]. On T2-weighted images the fluid collections within the tumor demonstrate variable, homogenous high signal intensity while the wall of the mass is represented by a low-signal-intensity rim[2,54,55]. Variable signal intensities on T1- and T2-weighted images depend on the presence of solid components, hemorrhage, and protein content[2,54,55]. On T1-weighted images, the signal intensity may change from hypointense to hyperintense while septations may be obscured, and only mild enhancement of the cyst wall is noted after Gd-DTPA administration, as protein concentration and viscosity of the cyst fluid increase. In contrast, on T2-weighted images, signal intensity of the cyst fluid may decrease. Similar changes of the typical MRI appearance of cystadenoma may be caused by internal hemorrhage[26]. MRI may disclose dilated intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts or demonstrate the relationship of the lesion to vascular structures and, thus, may be helpful in planning the surgical procedure.

Preoperative assumption that the lesion is benign based on US, CT or MR findings is not safe and therefore not recommended[48]. The presence of irregular thickness of the wall, mural nodules or papillary projections indicates the possibility of malignancy[2,7,45,53]. Papillary projections in the cyst can be seen on contrast-enhanced CT, and are characteristic of malignant neoplasm[4]. However, there are cases in which papillary projections are not shown clearly on CT. Hypervascularity of mural nodules on CT during arteriography may also indicate malignancy of the lesion[45]. Septation without nodularity suggests the diagnosis of cystadenoma whereas septation with mural or septal nodules, papillary infoldings, dicrete solid masses, and thick, coarse calcifications is suggestive of cystadenocarcinoma[4,7,54]. Changes in appearance of the cyst wall may also suggest malignant transformation[45]. Despite these features, however, imaging differentiation criteria between biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma have not yet been established[14,17,33].

Angiography is advisable and may be helpful both in clarifying the hepatic arterial anatomy and in differentiating cystadenocarcinoma from benign cystadenoma but seems not essential while the resectability of the tumor is assessed. Common findings include an avascular or hypovascular lesion with a faint rim of contrast-material accumulation in the wall and septa of the mass in the parenchymal phase and, occasionally, a tumor blush at the periphery corresponding to the papillary infoldings along with displacement of regional intrahepatic vessels[1,11,12,22,26]. Signs raising the suspicion of malignancy are considered to be attenuated intracystic vessels, stretching of thin hepatic arteries, intracystic hypervascular mural nodules, irregular calibers of the peripheral arteries in the arterial phase, and light stains in the parenchymal phase[40,45]. Attenuated arteries and tumor stain at the central portion of an avascular or hypovascular lesion are the typical angiographic features of a cystadenocarcinoma[40].

Although difficult, correct preoperative and/or intraoperative diagnosis of cystadenomas and cystadeno-carcinomas is of utmost importance in planning the appropriate surgical procedure. Among all intraoperative diagnostic and surgical procedures intraoperative ultrasound is considered the most sensitive[58]. Intraoperative US can be helpful for the diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma[3,18] and determining its resectability[11]. It may occasionally allow the surgeon to differentiate between the smooth wall of a cystadenoma and the infiltrative wall of a cystadenocarcinoma[18]. However, it cannot usually confirm the relationship between the tumor and the bile system while it may be difficult to distinguish an extrahepatic cystadenoma from a pancreatic cystadenoma because of their similar appearance on US[51]. In patients operated laparoscopically, laparoscopic ultrasonography has been reported as an essential supplement to inspection of the lesion via laparoscopy[14].

Intraoperative cholangiography is also considered very helpful since it can demonstrate both intrahepatic[12,18] and extrahepatic lesions[23]. It may allow fluid aspiration for cytology[18] and may reveal communication between the lesion and the biliary system[18] although not always[12]. In addition, it can be performed after the surgical procedure in order to exclude any bile duct injuries or retained cysts[18]. It has been proposed that intraoperative cholangiography and/or choledochoscopy should be performed to diagnose extrahepatic cystadenomas[23].

Treatment and prognosis

Resection is the management of choice for all multilo-culated cystic hepatic lesions[19,59]. If a cystadenoma is suspected or has been diagnosed, surgery is indicated even in asymptomatic patients, since cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma cannot be reliably differentiated on the basis of radiologic and macroscopic criteria[1,5,6,10,33,48,54]. The extent of resection remains to be determined since partial resection with occasional ablation of the residual cyst using electrocautery or argon beam coagulation and/or omentopexy[14,33,60], and lobectomy[14,61] as well as wedge resection[14] and enucleation[14,19,50,62] have been reported.

In cases of communication of an intrahepatic cystadenoma with the biliary tract, biliary fistulae should be confirmed[45]. When such fistulae are identified, resection of the tumor should be supplemented with suture closure of the fistulae[14,45] or resection of the affected bile duct and bilioenteric reconstruction particularly if postoperative leak or intrahepatic biliary obstruction after suture control is concerned[14,41]. In treatment of extrahepatic cystadenomas, resection of the tumor should be supplemented with resection of the affected bile duct and bilioenteric anastomosis[17]. In cases of compression of intrahepatic or extrahepatic ducts, postoperative cholangiography may be performed to identify resolution of biliary compression[45].

Incidental finding of a cystadenoma during surgery for other clinical indications demands a complete surgical resection of the tumor[6]. Although incidental finding of a cystadenoma after open or laparoscopic fenestration of a hepatic cyst also requires complete resection, it has been proposed that after complete enucleation of the cyst, strict follow-up could be considered as the definitive treatment, demanding the surgical intervention only in case of recurrence or high suspicion of malignancy[6,63]. However, recurrence of symptoms 8 and 18 months after laparoscopic fenestration of an unsuspected cystadenoma has been reported[64].

Total tumor extirpation with a wide margin of normal liver provides a chance for cure[5,7,10,65]. Techniques other than complete excision for treatment of cystic hepatic lesions such as internal drainage, aspiration, marsupialization, sclerosis, Roux-en Y cyst-bowel anastomosis or partial resection should not be performed in cystadenomas because they may result in biliary obstruction, secondary infection or sepsis, rupture, hemorrhage, continued tumor growth, recurrence or late malignant transformation of the tumor[3,7,10,11,14,17,19,25,45,51]. Benign biliary cystadenomas are believed to transform to cystadenocarcinomas even decades after partial resection although few of these lesions have been reported[26,36,60]. Moreover, patients with hepatobiliary cystadenomas have been found to be over 10 years younger than those with cystadenocarcinomas[7]. Cystadenomas should therefore be appreciated as premalignant lesions[7,10,17,33,45,60] while cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma may be considered a different form of the same disease[15]. Furthermore, cystadenoma cannot be easily differentiated preoperatively or intraoperatively from cystadenocarcinoma and total surgical resection should always be considered[1,5,6,10,13,33,48,54]. Since complete surgical resection is the only safe way of eliminating such a danger and differentiating the two entities, such tumors should be completely excised[60,61].

In addition, experience with techniques such as aspiration, fenestration, internal drainage, intratumoral sclerosant application or partial resection of cystadenomas is disappointing since the recurrence rate is extremely high ranging from 90% to 100%[11,19,21,64,65] compared to 0%-10%[22,25,26,48,52,60] after radical resection. Similarly, Davies et al[17] reported that the recurrence rate for extrahepatic lesions is 50% after local excision from the bile duct wall compared to no recurrence after formal resection and bilioenteric reconstruction. Moreover, recurrence may be demonstrated even decades after subtotal resection[51] while consecutive recurrences in the same patient have also been reported[59].

Though still in evolution, laparoscopic surgery has an expanding role in the treatment of carefully selected patients with liver lesions and can achieve promising results[66]. There are very few reports on successful laparoscopic treatment of intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas[14,66] while no case of laparoscopically treated extrahepatic lesion has been reported. Even though laparoscopic treatment of intrahepatic cystadenomas has not been analyzed, provided that it is performed by expert liver as well as laparoscopic surgeons, the patients are carefully selected in terms of tumor size and location, and the tumor is completely excised, laparoscopic treatment is feasible and safe and may lead to similar results as open surgery[14,66].

The prognosis of patients with cystadenoma is very good if total excision of the lesion is performed[5,7,10,25,48,52]. In addition, cystadenocarcinomas may not show aggressive clinical behavior, and usually appear to have a slower growth rate and less frequent metastases or local invasion than other hepatic malignant neoplasms, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, and ovarian or pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas[48]. When treated with radical excision, they also have a generally good prognosis[48,52], particularly those with mesenchymal stroma, unless the tumor invades the adjacent liver tissue or neighboring organs, or metastases are present[33,39,48].