Published online Sep 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i36.5875

Revised: August 5, 2006

Accepted: August 12, 2006

Published online: September 28, 2006

AIM: To investigate plasma levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), an established marker of cardiac function, in patients with chronic hepatitis C during interferon-based antiviral therapy.

METHODS: Using a sandwich immunoassay, plasma levels of NT-proBNP were determined in 48 patients with chronic hepatitis C at baseline, wk 24 and 48 during antiviral therapy and at wk 72 during follow-up.

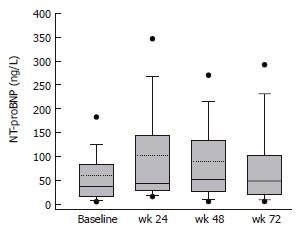

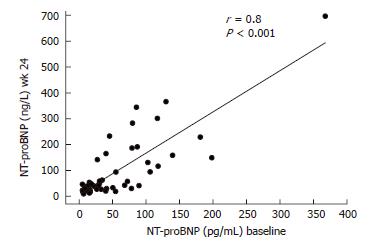

RESULTS: Plasma NT-proBNP concentrations were significantly increased (P < 0.05) at wk 24, 48 and 72 compared to the baseline values. NT-proBNP concentrations at baseline and wk 24 were closely correlated (r = 0.8; P < 0.001). At wk 24, 7 (14.6%) patients had NT-proBNP concentrations above 200 ng/L compared to 1 (2%) patient at baseline (P = 0.059). Six of these 7 patients had been treated with high-dose IFN-α induction therapy. In multiple regression analysis, NT-proBNP was not related to other clinical parameters, biochemical parameters of liver disease or virus load and response to therapy.

CONCLUSION: Elevated levels of NT-proBNP during and after interferon-based antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C may indicate the presence of cardiac dysfunction, which may contribute to the clinical symptoms observed in patients during therapy. Plasma levels of NT-proBNP may be used as a diagnostic tool and for guiding therapy in patients during interferon-based antiviral therapy.

- Citation: Bojunga J, Sarrazin C, Hess G, Zeuzem S. Elevated plasma levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in patients with chronic hepatitis C during interferon-based antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(36): 5875-5877

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i36/5875.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i36.5875

The current standard of care for patients with chronic hepatitis C is the combination treatment with (pegylated) interferon plus ribavirin[1,2]. Almost all patients experience side effects like fatigue, dyspnea and reduced physical activity. However, in many patients, these symptoms are not proportional to the decline of hemoglobin and resemble symptoms of heart failure.

Cardiotoxicity is assumed to be a rare complication of interferon therapy with few significant life-threatening cardiovascular effects reported[3,4]. A small number of cases of suspected interferon-induced cardiomyopathy have been documented and in most of the patients, cardiac toxicity was reversible following the cessation of the drug therapy[5].

Several studies have shown that plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) are reliable diagnostic and prognostic markers for cardiac disease[6,7] that correlate with symptoms of heart failure and the severity of systolic and diastolic dysfunction[8]. In addition, BNP also predicts death, first major cardiovascular events, heart failure and stroke[9].

In the present study, we assessed concentrations of circulating NT-proBNP in chronic hepatitis C patients before and during interferon-based antiviral therapy. Levels of this cardiac peptide were related to clinical, biochemical and virologic parameters in these patients.

The study population comprised of 48 patients (15 females and 33 males; mean age: 51 years, range: 33-76 years) with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. None of the patients had signs of heart failure, organic renal disease, thyroid disease, diabetes, cancer, or any other major diseases. All patients had normal cardiac physical examination and normal blood pressure. Thirty one patients were infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 6 with genotype 2, 10 with genotype 3 and 1 with genotype 4. All patients received interferon-based antiviral therapy for 48 wk. Sixteen patients received 3 Mio IU IFN-2b three times a week plus ribavirin 1000/1200 mg per day; 14 patients received 9 Mio IU IFN-2a per day for 2 wk, 6 Mio IU per day for 4 wk, 3 Mio IU per day for 6 wk and then 3x3 Mio IU per week plus ribavirin 1000/1200 mg per day; 11 patients received 10 Mio IU IFN-2b daily for 2 wk, then 5 Mio IU for 6 wk, 3 Mio IU for 16 wk and finally 3 Mio IU three times a week plus ribavirin 1000/1200 mg per day; 3 patients received 1.5 µg/kg PEG-IFN-2b for 4 wk, then 0.5 µg/kg plus 1000-1200 mg ribavirin; 2 patients received PEG 2a 180 µg plus 1000/1200 mg ribavirin; and 2 patients received PEG 2b 1.5 µg/kg plus ribavirin 800 mg daily.

All blood samples were drawn in the morning after an overnight fast. Blood samples for analysis of plasma NT-proBNP were collected, centrifuged and plasma was stored at -80°C until analysis. Plasma concentrations of NT-proBNP were measured by a sandwich immunoassay on an Elecsys 2010 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Blood samples were taken at baseline, at wk 24 and 48 during antiviral therapy, and at wk 72, i.e. 24 wk after the end of therapy.

Comparison of plasma NT-proBNP concentrations at baseline and during antiviral therapy and follow-up was performed with a Friedman repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on Ranks with an all pairwise multiple comparison procedure using the Student-Newman-Keuls method. Correlations were performed by the Spearman rank order correlation test. Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. A multiple regression model was used to evaluate the relation between plasma NT-proBNP concentrations at baseline, during antiviral therapy and follow-up on the one hand and clinical, biochemical and virologic parameters on the other hand. Values were expressed as Mean ± SE. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Plasma NT-proBNP concentrations were significantly higher at wk 24 of therapy (mean 102 ± 18.4 ng/L; median 44.3 ng/L, range 9.2-696.4; P < 0.05), wk 48 of therapy (mean 89 ± 12.4 ng/L; median 52.4 ng/L, range 5.0-376.4; P < 0.05) and remained elevated in the follow-up period (mean 83 ± 14.1 ng/L; median 49.0 ng/L, range 5.0-433.3; P < 0.05) compared to baseline values before treatment (mean 59 ± 9.4 ng/L; median 37.1 ng/L, range 5.0-367.60; Figure 1). NT-proBNP concentrations at baseline and wk 24 were closely correlated (r = 0.8; P < 0.001; Figure 2). At wk 24, 7 (14.6%) patients had NT-proBNP concentrations above 200 ng/L compared with 1 (2%) patient at baseline (P = 0.059). Six of these 7 patients had received high-dose of interferon at the beginning of the treatment as an induction therapy, whereas 1 had received standard regimen with pegylated IFN once a week (P = 0.21).

In multiple regression analysis, plasma NT-proBNP concentrations before therapy were not related to other clinical or biochemical parameters of liver disease or virologic parameters and response to therapy (Table 1). However, elevated plasma NT-proBNP concentrations at wk 24 of therapy were predicted by plasma NT-proBNP concentrations before therapy (P < 0.01; Table 1).

| Variables | Value(mean ± SE) | Regressioncoefficient | Standarderror | P |

| Age (yr) | 51 ± 1.6 | -0.03 | 0.8 | 0.96 |

| Body weight (kg) | 76.5 ± 1.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.76 |

| ALT (U/L) | 59 ± 5.9 | 0.3 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| AST (U/L) | 31 ± 2.9 | -0.3 | 0.84 | 0.67 |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 41 ± 6.1 | -0.01 | 0.2 | 0.95 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 77 | 105.7 | 0.47 |

| γ-globulins (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 0.07 | 2.4 | 17.7 | 0.89 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 95 ± 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.51 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 4.8 ± 0.04 | -9.1 | 33.2 | 0.78 |

| Cholinesterase (kU/L) | 6.1 ± 0.23 | -1.4 | 6.1 | 0.81 |

| Baseline HCV RNA (copies/mL) | 4 705 302 ± 984 817 | 0.02 × 10-5 | 0.2 × 10-5 | 0.31 |

| log decline of HCV RNA (baseline wk 12) | 2.7 ± 0.12 | -5.9 | 16.0 | 0.71 |

The present study showed that circulating NT-proBNP concentrations increased significantly in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection during interferon-based antiviral therapy with a trend to affect patients more often that had received high-dose of interferon at the beginning of the therapy. This effect persisted during follow-up up to 24 wk after the end of therapy.

The findings of the present study may have important implications for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection during interferon-based antiviral therapy. Most patients complain about fatigue, dyspnea and reduced physical capacity during antiviral therapy which is frequently discontinued for these reasons. The pathogenesis of these symptoms is not well understood and sometimes attributed to the development of anemia. However, it seems possible that these patients experience cardiac impairment causing or at least contributing to these symptoms. Testing of NT-proBNP may serve as a screening marker for cardiac insufficiency in the differential diagnosis of fatigue and dyspnea and may alleviate the decision for further diagnostic testing of cardiac function as it has been described for other groups of patients[10-13]. Besides diagnostic consequences, evaluation of NT-proBNP may have therapeutic consequences for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection during antiviral therapy with interferons as well. In patients with known congestive heart failure, elevated plasma BNP concentrations could be reduced by treatment with ACE inhibitors[14], angiotensin II receptor antagonists[15] as well as treatment with diuretics and vasodilators[16]. As a consequence, plasma NT-proBNP concentrations may guide the intensity of pharmacotherapy as some interventional studies have suggested[17,18].

In conclusion, this is probably the first study reporting elevated levels of NT-proBNP during and after interferon-based antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. This may indicate the presence of cardiac dysfunction and explain the clinical symptoms of patients during therapy and the discrepancy between these symptoms and the severity of anemia. Further prospective studies quantifying symptoms and correlating these with echocardiographic parameters are needed to confirm this association. In addition, interventional studies are required whether therapy of cardiac insufficiency can improve the side effect profile of interferon-based therapy in patients treated for chronic hepatitis C.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Fleig WE, Krummenerl P, Lesske J, Dienes HP, Zeuzem S, Schmiegel WH, Häussinger D, Burdelski M, Manns MP. [Diagnosis, progression and therapy of hepatitis C virus infection as well as viral infection in children and adolescents--results of an evidenced based consensus conference of the German Society for Alimentary Metabolic Disorders and and in cooperation with the Hepatitis Competence Network]. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:703-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1-46. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Zimmerman S, Adkins D, Graham M, Petruska P, Bowers C, Vrahnos D, Spitzer G. Irreversible, severe congestive cardiomyopathy occurring in association with interferon alpha therapy. Cancer Biother. 1994;9:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Condat B, Asselah T, Zanditenas D, Estampes B, Cohen A, O'Toole D, Bonnet J, Ngo Y, Marcellin P, Blazquez M. Fatal cardiomyopathy associated with pegylated interferon/ribavirin in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:287-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sonnenblick M, Rosin A. Cardiotoxicity of interferon. A review of 44 cases. Chest. 1991;99:557-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Doust JA, Glasziou PP, Pietrzak E, Dobson AJ. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of natriuretic peptides for heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1978-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Clerico A, Emdin M. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic relevance of the measurement of cardiac natriuretic peptides: a review. Clin Chem. 2004;50:33-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koglin J, Pehlivanli S, Schwaiblmair M, Vogeser M, Cremer P, vonScheidt W. Role of brain natriuretic peptide in risk stratification of patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1934-1941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Omland T, Wolf PA, Vasan RS. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:655-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 1121] [Article Influence: 53.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cabanes L, Richaud-Thiriez B, Fulla Y, Heloire F, Vuillemard C, Weber S, Dusser D. Brain natriuretic peptide blood levels in the differential diagnosis of dyspnea. Chest. 2001;120:2047-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morrison LK, Harrison A, Krishnaswamy P, Kazanegra R, Clopton P, Maisel A. Utility of a rapid B-natriuretic peptide assay in differentiating congestive heart failure from lung disease in patients presenting with dyspnea. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 437] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakamura M, Endo H, Nasu M, Arakawa N, Segawa T, Hiramori K. Value of plasma B type natriuretic peptide measurement for heart disease screening in a Japanese population. Heart. 2002;87:131-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Remme WJ, Swedberg K. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1527-1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1017] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Motwani JG, McAlpine H, Kennedy N, Struthers AD. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as an indicator for angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1993;341:1109-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Latini R, Masson S, Anand I, Judd D, Maggioni AP, Chiang YT, Bevilacqua M, Salio M, Cardano P, Dunselman PH. Effects of valsartan on circulating brain natriuretic peptide and norepinephrine in symptomatic chronic heart failure: the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT). Circulation. 2002;106:2454-2458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Johnson W, Omland T, Hall C, Lucas C, Myking OL, Collins C, Pfeffer M, Rouleau JL, Stevenson LW. Neurohormonal activation rapidly decreases after intravenous therapy with diuretics and vasodilators for class IV heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1623-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Murdoch DR, McDonagh TA, Byrne J, Blue L, Farmer R, Morton JJ, Dargie HJ. Titration of vasodilator therapy in chronic heart failure according to plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: randomized comparison of the hemodynamic and neuroendocrine effects of tailored versus empirical therapy. Am Heart J. 1999;138:1126-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Yandle TG, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Richards AM. Treatment of heart failure guided by plasma aminoterminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-BNP) concentrations. Lancet. 2000;355:1126-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 971] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |