Published online Sep 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5509

Revised: September 28, 2005

Accepted: October 26, 2005

Published online: September 14, 2006

AIM: To investigate the prevalence of H pylori associated corpus-predominant gastritis (CPG) or pangastritis, severe atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia (IM) in patients without any significant abnormal findings during upper-GI endoscopy.

METHODS: Gastric biopsies from 3548 patients were obtained during upper GI-endoscopy in a 4-year period. Two biopsies from antrum and corpus were histologically assessed according to the updated Sydney-System. Eight hundred and forty-five patients (mean age 54.8 ± 2.8 years) with H pylori infection and no peptic ulcer or abnormal gross findings in the stomach were identified and analyzed according to gastritis phenotypes using different scoring systems.

RESULTS: The prevalence of severe H pylori associated changes like pangastritis, CPG, IM, and severe atrophy increased with age, reaching a level of 20% in patients of the age group over 45 years. No differences in frequencies between genders were observed. The prevalence of IM had the highest increase, being 4-fold higher at the age of 65 years versus in individuals less than 45 years.

CONCLUSION: The prevalence of gastritis featuring at risk for cancer development increases with age. These findings reinforce the necessity for the histological assessment, even in subjects with normal endoscopic appearance. The age-dependent increase in prevalence of severe histopathological changes in gastric mucosa, however, does not allow estimating the individual risk for gastric cancer development-only a proper follow-up can provide this information.

- Citation: Leodolter A, Ebert MP, Peitz U, Wolle K, Kahl S, Vieth M, Malfertheiner P. Prevalence of H pylori associated ‘high risk gastritis’ for development of gastric cancer in patients with normal endoscopic findings. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(34): 5509-5512

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i34/5509.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5509

H pylori infection is an established risk factor for development of gastric cancer[1,2]. According to the model of carcinogenesis of the intestinal type adenocarcinoma proposed by Correa, the multi-step development starts from the condition of a chronic active gastritis, followed by glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally gastric adenocarcinoma[3]. The risk for gastric cancer also increases in the presence of corpus-predominant gastritis as well as a pangastritis[4]. Since only a small subset of H pylori infected subjects will develop gastric cancer, from a clinical point of view it is a major difficulty to identify those patients with H pylori infection who are at a higher risk to develop gastric cancer. Therefore there is a need to identify patients, who have these advanced changes in gastric mucosa. The combination of these risk factors (gastric cancer risk index) has been proven to be a simple way to better estimate the risk for gastric cancer development[5,6]. The gastric cancer risk index has been proven to be independently increased in both histological types of gastric cancer: the intestinal as well as the diffuse type.

The aim of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of advanced histopathological changes in gastric mucosa in patients with normal appearance of gastric mucosa during upper GI-endoscopy.

A total of 3548 first time upper GI-endoscopies were performed in the Endoscopic Unit of the University of Magdeburg over a 4-year period. During this period, it was the policy in our department to obtain gastric specimens from all patients regardless of the appearance of the mucosa to establish the pattern of gastritis in those patients. Patients with contraindication to obtain gastric specimens or previous endoscopy with histological investigation were not included.

Around one half of the investigated patients were outpatients, and the other half hospitalized patients. After the investigation, an endoscopic report was entered in a computer-based database. Upper GI-endoscopy was performed by several experienced gastroenterologists. Two gastric specimens from the corpus and antrum, respectively, were taken and analysed histologically according to the Sydney-System in all patients. Histological results were documented in the same computer-based database. Histological examination was performed by different pathologists from the Institute of Pathology at the University of Magdeburg. All slides have been re-evaluated for the needs of this study by a single experienced gastrointestinal pathologist in a blinded way without being aware of clinical or endoscopic diagnoses and prior histological reports. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Magdeburg and all patient data were made anonymous to protect patients’ identity.

The database was retrospectively analyzed for those patients who had a normal endoscopical appearance of gastric mucosa or simply signs of gastritis or duodenitis. Thus all patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers, GI-bleeding, and upper GI-malignancy were excluded. The presence of reflux oesophagitis or hiatal hernia was not an exclusion criterion. Furthermore, patients known to be treated with proton-pump inhibitors or with indirect evidence for this treatment by histological observation of parietal cell hypertrophy were excluded. H pylori infection was determined by positive culture, rapid urease test and/or histology.

We identified 845 H pylori positive patients who fulfilled the predefined criteria. Age distribution and gender are given in Table 1. In these patients the following parameters were calculated according to the histological examination: (1) Corpus-predominant gastritis[4]: Higher degree of neutrophilic infiltration in the corpus compared to the antrum; (2) Pangastritis[4]: Equal degree of neutrophilic infiltration in the corpus and in the antrum; (3) Antrum-predominant gastritis[4]: Higher degree of neutrophilic infiltration in the antrum compared to the corpus; (4) Intestinal metaplasia[4,7]: Absence or presence in any investigated specimen from antrum or corpus; (5) Severe atrophy[4,8]: Severe loss of glands; not diagnosed in the antrum when only a few intestinal crypts were observed in the whole specimen; (6) Antrum and corpus gastritis score: Score by total sum of grade of gastritis (mild = 1, moderate = 2, marked = 3 infiltration with lymphocytes and plasma cells) and activity of gastritis (mild = 1, moderate = 2, marked = 3 infiltration with neutrophilic granulocytes) either in the antrum or in the corpus, a maximum of a sum of 6 points in the antrum and in the corpus for each individual person; (7) Gastric cancer risk index[5,6]: 1 point scored for at least moderate infiltration with lymphocytes and plasma cells in the corpus and less or equal infiltration in the antrum, 1 point scored for at least moderate infiltration with neutrophilic granulocytes in the corpus and less or equal infiltration in the antrum, 1 point scored for the detection of intestinal metaplasia in the antrum or in the corpus, a maximum of 3 points for each individual person.

| Endoscopic normal gastric mucosawith H pylori infection | |

| Number (n) | 845 |

| Mean age (yr) | 54.8 (18-87) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 450/845 (53.2%) |

| Female | 395/845 (46.8%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| < 35 | 114/845 (13.5%) |

| 35-44 | 120/845 (14.2%) |

| 45-54 | 151/845 (17.9%) |

| 55-64 | 199/845 (23.6%) |

| 65-74 | 166/845 (19.6%) |

| > 75 | 95/845 (11.2%) |

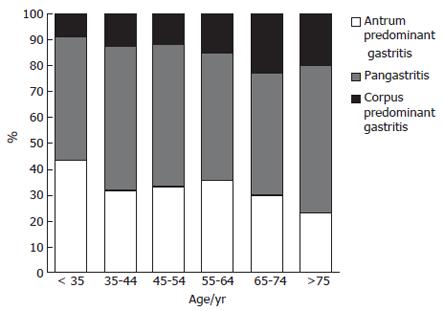

The frequency of corpus-predominant gastritis was significantly increased with age (Kruskal-Wallis test, P < 0.01). While in the group of patients of less than 35 years old only 8.8% had a corpus-predominant gastritis, and the number increased to 22.9% between the ages of 65-75 years (Figure 1). The highest increase was observed between the age groups of 45-54 years (13.8%) and 55-64 years (23.1%). The number of patients with pangastritis remained constant, whereas the frequency of antrum-predominant gastritis declined over time.

The frequencies of intestinal metaplasia in different age groups increased significantly in an almost linear pattern (r2 = 0.9585, P < 0.001). The increase rate was 0.71% per year (95% CI 0.51-0.92). Nearly 40% of patients over 65 years had intestinal metaplasia (Table 2). For example, the relative risk for a patient at the age of 64-75 years was 5.0 (95% CI 2.6-9.6) times higher compared to a patient younger than 35 years. Intestinal metaplasia was more frequent in the corpus compared to the antrum (20.7% vs 6.7%), and those located only in the antrum were a rare event (3.4%).

| Age (yr) | Overall IM | IM only inthe antrum | IM only in thecorpus | IM in antrumand corpus |

| < 35 | 9/114 (7.9%) | 1/114 (0.9%) | 7/114 (6.1%) | 1/114 (0.9%) |

| 35-44 | 14/120 (11.7%) | 2/120 (1.7%) | 12/120 (10.0%) | 0/120 (0.0%) |

| 45-54 | 28/151 (18.5%) | 7/151 (4.6%) | 18/151 (11.9%) | 3/151 (2.0%) |

| 55-64 | 50/199 (25.1%) | 7/199 (3.5%) | 35/199 (17.6%) | 8/199 (4.0%) |

| 64-75 | 65/166 (39.2%) | 6/166 (3.6%) | 51/166 (30.7%) | 8/166 (4.8%) |

| > 75 | 38/95 (40.0%) | 6/95 (6.3%) | 24/95 (25.2%) | 8/95 (8.4%) |

| Differences between age groups | P < 0.001 (χ2-test) | P < 0.001 (χ2-test) | P < 0.001 (χ2-test) | P < 0.001 (χ2-test) |

The frequencies of severe atrophy and the antrum/corpus gastritis score in the different age groups are provided in Table 3. Severe atrophy was close to 2% in the group younger than 65 years and increased up to 11.2% at the age over 75 years. The antrum gastritis score was almost equal in all age groups (mean 3.27 ± 0.95). The corpus gastritis score increased significantly with age [increase of 0.01 per year (95% CI 0.006-0.016)].

| Age (yr) | Severe atrophy | Antrum gastritisscore | Corpus gastritisscore |

| < 35 | 0/114 (0.0%) | 3.36 ± 0.90 | 2.49 ± 1.17 |

| 35-44 | 2/120 (1.7%) | 3.17 ± 0.86 | 2.73 ± 1.02 |

| 45-54 | 3/151 (2.0%) | 3.32 ± 1.04 | 2.85 ± 1.04 |

| 55-64 | 4/199 (2.0%) | 3.38 ± 0.94 | 2.93 ± 1.17 |

| 64-75 | 9/166 (5.4%) | 3.20 ± 0.92 | 2.98 ± 1.08 |

| > 75 | 9/95 (11.2%) | 3.08 ± 0.96 | 3.06 ± 1.15 |

| Differences between age groups | P < 0.001 (χ2-test) | NS (ANOVA) | P < 0.001 (ANOVA) |

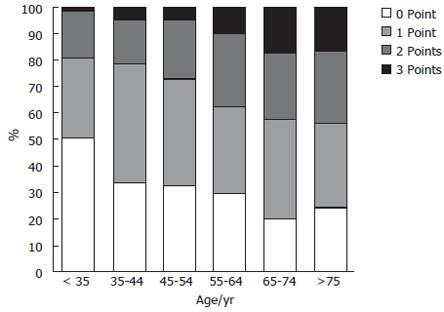

The gastric cancer risk index showed a significant shift to a higher index with age (Kruskal-Wallis test; P < 0.0001; Figure 2). At least 10% of the individuals older than 55 years had a score of 3 points, and more than 25% of them had a score of 2 points.

Comparison of the different scoring systems like gastric cancer index and phenotype of gastritis showed a significant correlation (P < 0.001, χ2-test; Table 4). This was expected because the phenotype of gastritis was included in the gastric cancer index. Nevertheless, the definitions for predominant gastritis were very different (see METHODS). The group with the highest risk for gastric cancer according to Uemura et al[4] might be these with the corpus-predominant gastritis (n = 130), whereas the risk might be highest for those with a gastric cancer index of 3 (n = 80), and the overlapping group contained only 44 patients (26.5%).

| Phenotype of gastritis | Gastric cancer risk index | |||

| 0 point | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | |

| Antrum-predominant gastritis | 156 | 104 | 21 | 0 |

| Pangastritis | 107 | 178 | 113 | 36 |

| Corpus-predominant gastritis | 2 | 22 | 62 | 44 |

Histological alterations of the gastric mucosa such as corpus-predominant gastritis, pangastritis, intestinal metaplasia or severe atrophy are proposed to carry an increased risk for gastric cancer in H pylori infected individuals. In our study we observed a strong association of intestinal metaplasia, atrophy as well as corpus-predominant gastritis with increasing age. Our results represent the frequency of histopathological changes in a country with a lower gastric cancer prevalence compared to other parts of the world (i.e. China or Japan). This might be of importance for future investigational trials on this topic.

We investigated only patients with normal appearing gastric mucosa or no grossly visible changes at endoscopy. In such a setting, often a rapid urease test would be performed by most investigators to test for H pylori only; therefore histopathological changes will not be diagnosed. However, our data clearly indicate that there is a need to obtain gastric specimens in routine endoscopy, even if the macroscopic appearance is to a greater or lesser extent normal. There is much evidence that several phenotypic changes in the gastric mucosa are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. In a large prospective study from Japan[4] only patients with H pylori infection developed gastric cancer. A closer look at the data revealed that certain histopathological findings increased the risk dramatically. In fact, the presence of intestinal metaplasia (RR 6.4), severe atrophy (RR 4.9), pangastritis (RR 15.6), and, most strikingly, corpus-predominant gastritis (RR 34.5) was associated with an increased risk for gastric cancer. An additional aspect in this study was the fact that about 60% of the patients who developed gastric cancer, had no initial pathological findings during upper GI-endoscopy and were classified as non-ulcer dyspepsia. It demonstrates the importance to obtain gastric specimen during upper GI-endoscopy even though the macroscopic findings are normal.

The optimal strategy for patients with risk lesions for gastric cancer has not been established. One option might be to eradicate H pylori infection. It is well known that corpus-predominant or pangastritis will be healed after successful eradication therapy; on the other hand, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia will persist constantly according to systematic review of the published literature[9]. In addition, a large randomized trial from China indicates that the point of no return might be already achieved when atrophy or intestinal metaplasia are observable[10]. In that trial, performed in more than 1600 healthy volunteers from Fujian Province, a significant reduction of gastric cancer incidence in an 8-year follow-up period by H pylori eradication was only observed in those patients without intestinal metaplasia or atrophy in the gastric mucosa in the beginning of the study. One possible conclusion from this study is that patients with those histopathological changes have to be included in an endoscopic surveillance program, but it is unknown which intervals are necessary and how cost-effective such a strategy might be. This will have to be the topic of future investigational trials.

The combination of histopathological features is a promising tool, since there is a clear need to identify those patients at risk for the development of gastric cancer. While the scoring system used in the trial by Ley et al[11] is probably too complex to use in general, the gastric cancer index might be more promising to use in clinical practice. This score includes the type of gastritis as well as the presence of intestinal metaplasia and has been proven to be highly predictive for the presence of gastric carcinoma[5]. We identified 80 (9.5%) out of 845 patients with normal endoscopic appearance and the highest possible gastric cancer risk score of 3. Especially in those patients an endoscopic surveillance might be necessary; however, the final proof of any improvement for the individual patient is yet missing.

In the trial of Uemura et al[4] the highest risk was found in those patients with a corpus-predominant gastritis; nevertheless, a marked risk was observed in those with pangastritis, also. Pangastritis was very frequently diagnosed in our population (51.3%). The significance of this finding therefore will have to be verified.

Our results indicate that there is a need to obtain gastric biopsies during upper GI-endoscopy, even if the macroscopic appearance is normal or without any gross pathology. The prevalence of gastritis associated with an increased risk for cancer development increases with age. The individual risks for gastric cancer development remain to be established by the follow-up. H pylori eradication therapy alone might not be sufficient enough to prevent gastric cancer in patients with advanced changes in the gastric mucosa. From the actual perspective, and with regard of the literature, interventions have to be implemented earlier, before advanced changes in gastric mucosa caused by H pylori occur or, more worthwhile, preventing being infected with H pylori.

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2805] [Cited by in RCA: 2739] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, Yarnell JW, Stacey AR, Wald N, Sitas F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991;302:1302-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 925] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3187] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meining A, Kompisch A, Stolte M. Comparative classification and grading of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in patients with gastric cancer and patients with functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:707-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meining A, Bayerdörffer E, Müller P, Miehlke S, Lehn N, Hölzel D, Hatz R, Stolte M. Gastric carcinoma risk index in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:311-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Meining AG, Bayerdörffer E, Stolte M. Helicobacter pylori gastritis of the gastric cancer phenotype in relatives of gastric carcinoma patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:717-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heikkinen M, Vornanen M, Hollmén S, Färkkilä M. Prognostic significance of antrum-predominant gastritis in functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hojo M, Miwa H, Ohkusa T, Ohkura R, Kurosawa A, Sato N. Alteration of histological gastritis after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1923-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1046] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ley C, Mohar A, Guarner J, Herrera-Goepfert R, Figueroa LS, Halperin D, Johnstone I, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric preneoplastic conditions: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:4-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |