Published online Sep 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i33.5416

Revised: March 30, 2006

Accepted: May 25, 2006

Published online: September 7, 2006

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation is a very rare complication. An unusual mechanism aggravating it is reported. A 33-year-old man with end-stage hepatitis B liver cirrhosis underwent a piggyback orthotopic liver transplantation using a full-size cadaveric graft. Two months after transplantation, he developed gross ascites refractory to maximal diuretic therapy. Doppler ultrasound showed patent portal and hepatic veins. Serial computed tomography scans revealed a hypoperfused right posterior segment of the liver which subsequently underwent atrophy. Hepatic venography demonstrated a high-grade stenosis with an element of torsion of venous drainage at the anastomosis. The stenosis was successfully treated with repeated percutaneous balloon angioplasty. The patient remained asymptomatic six months afterwards with complete resolution of ascites and peripheral edema. We postulate that liver allograft segmental hypoperfusion and atrophy may aggravate or result in a hepatic venous outflow problem by the mechanism of torsion effect. Percutaneous balloon angioplasty is a safe and effective treatment modality for anastomotic stenosis.

- Citation: Ng SSM, Yu SCH, Lee JFY, Lai PBS, Lau WY. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation by an unusual mechanism: Report of a case. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(33): 5416-5418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i33/5416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i33.5416

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback orthotopic liver transplantation is a rare complication[1,2]. However, failure of early recognition and treatment of this complication can result in graft failure and even death of patients. We report here a case of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback orthotopic liver transplantation aggravated by an unusual mechanism and its successful treatment with percutaneous balloon angioplasty.

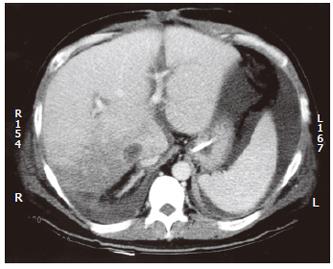

A 33-year-old man underwent cadaveric orthotopic liver transplantation for end-stage hepatitis B liver cirrhosis. A full-size graft was used and the caval anastomosis was performed with piggyback technique. Two weeks after transplantation, he was noted to have persistent leukocytosis (27-37 × 109/L) though he was afebrile. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was arranged to rule out intraabdominal collection or abscess formation. It revealed an extensive wedge-shaped region of low attenuation and decreased perfusion involving the right posterior segment of the liver graft, suggestive of an evolving infarct (Figure 1). He was treated conservatively with antibiotics and his white blood cell count gradually returned to a normal level.

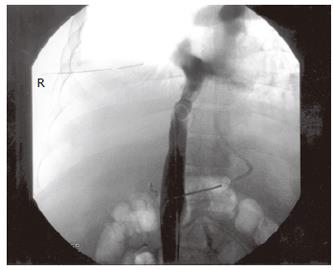

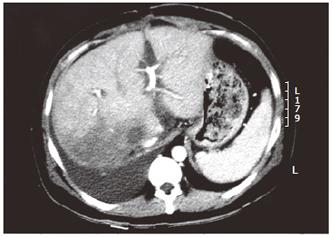

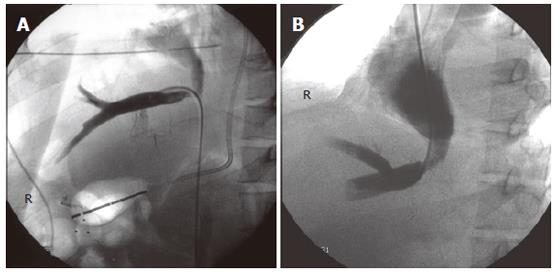

Six weeks later, the patient developed rapidly progressive abdominal distension and edema in the lower limbs. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed gross ascites, but the portal and hepatic veins were patent. The ascites failed to respond to maximal diuretic therapy and paracentesis. He subsequently underwent a venography which demonstrated a high-grade stenosis with an element of torsion of venous drainage at the anastomosis (pressure gradient 33 mmHg) (Figures 2 and 3). A repeated CT scan showed that the right posterior segment (previously hypoperfused segment) underwent atrophy (Figure 4). The venous outflow obstruction was treated with repeated percutaneous balloon angioplasty with a 10 mm and a 14 mm balloons (Figure 5A, 5B). Pressure gradient across the venous anastomosis was successfully reduced from 33 mmHg to 2 mmHg. The patient remained asymptomatic six months afterwards with complete resolution of ascites and peripheral edema.

Standard orthotopic liver transplantation, as described by Starzl et al[3] in 1963, involves an anhepatic phase during which the retrohepatic vena cava is resected. The main drawback of this classical technique is the decrease in venous return to the heart during this anhepatic phase, which causes haemodynamic instability and renal impairment. The introduction of the extracorporeal venovenous shunt has circumvented these physiological complications from occurring. In late 1960s, an alternative technique with vena cava preservation was described by Sir Roy Calne et al[4]. This technique was modified by Tzakis et al[5] in 1989 and has become the well known piggyback technique since then. It has the advantages of preservation of the vena caval blood flow and maintenance of venous return to the heart in the anhepatic phase. Haemodynamic alterations are avoided without the need of venovenous bypass. Many transplant centres are now favouring the piggyback technique as the technique of choice in both paediatric and adult liver transplantation.

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction from anasto-motic stricture is a very rare complication after piggy-back orthotopic liver transplantation, particularly in adult recipients who receive full-size liver grafts. In a retrospective study of 1112 piggyback liver transplantations performed in seven transplant units in Spain, the reported incidence of hepatic venous outflow obstruction is about 1%[1]. In another review of 264 piggyback transplantations performed at Stanford University Medical Center, only two patients were found to have developed venous outflow obstruction, representing an incidence of 0.8%[2]. The causes of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation are generally believed to be due to either anastomotic discrepancy or kinking of the venous anastomosis[6,7]. Paediatric recipients receiving reduced-size liver grafts are more prone to develop this complication because of size discrepancy between the donor suprahepatic vena cava and the recipient vein cuff. The presence of a wide empty subphrenic space and the lack of peritoneal attachments are other possible factors that permit a small liver graft to rotate around the venous anastomosis axis and hence lead to anastomotic kinking and obstruction. In adult liver transplantation, graft torsion is less likely to happen if a full-size graft is used because this effect is virtually eliminated by the presence of both liver lobes.

In our patient, a full-size liver graft was used, and theoretically the risk of graft torsion and venous anastomotic kinking should be very low. However, this rare complication of hepatic venous outflow obstruction still arose. On serial CT scans of the abdomen after transplantation, the right posterior segment of the liver graft was shown to be ischaemic and hypoperfused initially. The subsequent atrophy of the same segment resulted in rotation which in turn led to the kinking of the venous anastomosis. This unusual mechanism of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation, to the best of our knowledge, has never been described in the literature before.

Patients with hepatic venous outflow obstruction usually present with massive ascites and bilateral lower limb edema between 2 and 16 mo post-transplantation, which is refractory to oral protein supplements and maximal diuretic therapy[1,2]. Some of the patients can develop acute Budd-Chiari syndrome early within the first week of post-transplantation[1]. Failure of recognition of this complication can result in graft failure and death of patients. Diagnosis must be confirmed by hepatic venography and a pressure gradient study. Emergency revision of anastomosis or even retransplantation is occasionally required to remedy the condition. Nowadays with the advancement of minimally invasive endovascular intervention, selected cases of hepatic venous outflow obstruction can be successfully treated with percutaneous balloon angioplasty and stenting[2,8,9]. The procedure is done under local anaesthesia with minimal morbidity and mortality. Symptoms of ascites and peripheral edema are relieved rapidly and dramatically after the treatment. Repeated balloon angioplasty is sometimes needed to treat recurrent stenosis. The combination of balloon angioplasty and stenting can improve the long-term durability of the treatment.

In conclusion, liver allograft segmental hypoperfusion and atrophy may aggravate or result in hepatic venous outflow obstruction by the mechanism of torsion effect. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction should be considered in all patients who present with intractable ascites after liver transplantation. Venography is mandatory for diagnosis. Percutaneous balloon angioplasty is a safe and effective treatment modality for anastomotic stenosis.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Parrilla P, Sánchez-Bueno F, Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, Mir J, Margarit C, Lázaro J, Herrera L, Gomez-Fleitas M, Varo E. Analysis of the complications of the piggy-back technique in 1112 liver transplants. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:2388-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sze DY, Semba CP, Razavi MK, Kee ST, Dake MD. Endovascular treatment of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback technique liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:446-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Von Kaulla KN, Hermann G, Brittain RS, Waddell WR. Homotransplantation of the liver in humans. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1963;117:659-676. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Calne RY, Williams R. Liver transplantation in man. I. Observations on technique and organization in five cases. Br Med J. 1968;4:535-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tzakis A, Todo S, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation with preservation of the inferior vena cava. Ann Surg. 1989;210:649-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stieber AC, Gordon RD, Bassi N. A simple solution to a technical complication in "piggyback" liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1997;64:654-655. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Malassagne B, Dousset B, Massault PP, Devictor D, Bernard O, Houssin D. Intra-abdominal Sengstaken-Blakemore tube placement for acute venous outflow obstruction in reduced-size liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Raby N, Karani J, Thomas S, O'Grady J, Williams R. Stenoses of vascular anastomoses after hepatic transplantation: treatment with balloon angioplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pfammatter T, Williams DM, Lane KL, Campbell DA Jr, Cho KJ. Suprahepatic caval anastomotic stenosis complicating orthotopic liver transplantation: treatment with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, Wallstent placement, or both. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:477-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |