INTRODUCTION

Ectopic varices outside the esophagogastric lesion are rare in patients with portal hypertension[1]. Among ectopic varices, rectal varices are comparatively common, but their rupture is often fatal although it is rarely reported[2]. Though there are several case reports of rectal varices treated with endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL)[3], endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS)[4,5], transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)[6,7] and surgery[8,9], no single effective method has yet been established. Kimura et al[10] have reported that a patient is successfully treated with a new interventional radiological procedure, double balloon-occluded embolotherapy (DBOE). We used the modified percutaneous transhepatic obliteration with sclerosant (MPTO) rather than DBOE in the treatment of giant rectal varices in our case.

CASE REPORT

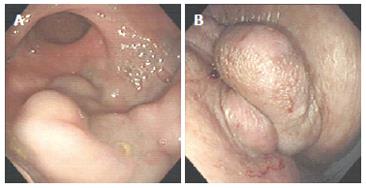

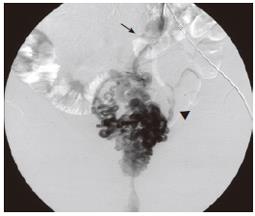

A 77-year old woman with liver cirrhosis had bleeding from esophageal varices, which was treated with EIS in 1992. She presented with profuse melena in March 1998 and was admitted to a nearby hospital due to shock. She received 2000 mL of packed red blood cells and was transferred to our hospital for further treatment. On admission, physical examination revealed moderate anemic conjunctiva without scleral icterus. Tense ascites was present without abdominal tenderness. The functional reserve of the liver was assessed as Child-Pugh grade B. Esophago- gastroduodenoscopy did not find recurrence of gastroesophageal varices. Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed huge tortuous rectal varices extending from outside the anus to the recto-sigmoid junction (Figure 1). Endoscopic Doppler ultrasonography (FG-32UA, Pentax Co., Ltd., EUB-555 US scanner, Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo Japan) revealed that the largest diameter of varices was 8.8 mm and the blood flow velocity was 5 cm/s. Percutaneous transhepatic inferior mesenteric venography and pelvic angiography revealed that the blood of the rectal varices was supplied by the inferior mesenteric vein and flowed into the bilateral internal iliac vein via the internal pudendal vein (Figure 2). Percutaneous transhepatic portography revealed narrowing of the portal vein trunk and thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein. For such extremely large rectal varices, treatment with EIS or EVL did not seem feasible. Instead, it was decided to treat her rectal varices with MPTO.

Figure 1 Flexible sigmoidoscopy reveals huge tortuous rectal varices extending from outside the anus to the recto-sigmoid junction (A: rectum, B: outside the anus).

Figure 2 Percutaneous transhepatic portography demonstrates that the rectal varices are supplied by the inferior mesenteric vein (arrow) and flowed into the bilateral internal iliac vein (arrowhead).

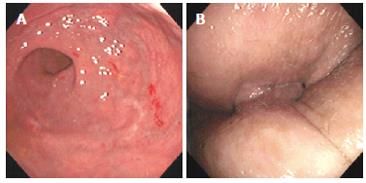

An occlusion balloon catheter (maximum external diameter of the balloon was 20 mm) and metallic coil were placed into the inferior mesenteric vein through the percutaneous transhepatic portogram route. When the rectal varices were fully visualized and contrast medium did not flow into the internal iliac vein, 5 mL of absolute ethanol was injected through the occluded inferior mesenteric vein followed by 7 mL of 5% ethanolamine oleate iopamidol (EOI) (Figure 3). The balloon was kept inflated for about 24 h. Twenty-four hours after the embolotherapy, PTP detected no blood flow in the rectal varices. There were no major complications during hospitalization. Four weeks after the embolotherapy, the sizes of the varices became markedly smaller (Figure 4). No rectal variceal bleeding occurred after treatment.

Figure 3 The sclerosant stagnates in the varices as a result of occlusion of the blood flow of the inferior mesenteric vein.

Figure 4 Sigmoidoscopy reveals disappearance of huge tortuous rectal varices extending from outside the anus to the recto-sigmoid junction (A: rectum; B: outside the anus).

DISCUSSION

Rectal varices result from dilated submucosal veins which extend from the dentate line into the rectum and represent the portosystemic collaterals between the superior rectal vein flowing into the inferior mesenteric vein, and the middle and inferior rectal veins draining into the internal iliac vein[11,12]. They are thought to be distinct from hemorrhoids, which do not occur in the rectum and have no direct communication with the portal circulation[12-14].

The first case of rectal varices was reported in 1954[15]. Izsak and Finlay[16] have reported 29 cases and Gudjonsson et al[17] have reviewed 69 cases of colonic varices since then. The incidence of colonic varices is low and has been reported to be 0.07%[18].

The most common underlying condition associated with rectal varices is portal hypertension, which is present in approximately three-fourths of all cases[17]. Other causes include localized portal hypertension resulting from blood flow disturbances through the mesenteric veins as a result of postoperative adhesion[19], splenic vein obstruction associated with pancreatitis[20], and carcinoid-induced mesenteric vein obstruction[21]. In addition, familial vascular anomalies[22], congenital vascular anomalies[23], and congestive heart failure[17] have been suggested as the possible causes of rectal varices. In our case, the patient received esophageal sclerotherapy six years ago. Keane et al[24] have reported a case of massive bleeding from rectal varices following repeated injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. An incidental risk of rectal varices after eradication of esophageal varices seems to be increased where portal hypertension is present.

Previously reported therapies for rectal varices include EIS[4,5], EVL[3], TIPS[6,7], surgery[8], and more conservative therapies such as drip infusion of vasopressin[25]. There is no standardized treatment for rectal varices, but rectal varices are accessible through standard endoscopy. Several studies have reported their successful treatment with sclerosant injection or band ligation. Endoscopic therapy with sclerosant is not so satisfactory, especially for large rectal varices, because sclerosant may be diluted in large varices beyond a concentration sufficient to obliterate the varices and there may be a risk of developing severe complications, such as pulmonary embolism, due to the flow of high doses of sclerosant into the systemic circulation. EVL can be used to treat active bleeding from rectal varices as an emergency treatment modality. Norton et al[26] reported that if the entire varix cannot be banded there is a risk of causing a wide defect in the varix after sloughing of the band, rendering the banding technique unsafe for large rectal varices.

Since surgery imposes a substantial burden and risk on patients, it may be advisable to reserve it for patients with Child-Pugh class A and extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis as the cause of portal hypertension. The efficacy of mobilization therapy or portosystemic shunt therapy using radiological techniques in the treatment of bleeding ectopic varices is rarely reported[27]. There are some reports on successful treatment of severe rectal varices with TIPS[6,7]. However, other reports showed that patients may die of rapidly progressive hepatic failure after TIPS procedure[28]. We have only used it in the treatment of patients on a waiting list for liver transplantation. Only one report on embolization therapy for rectal varices is available in 1900 and 2005. Kimura et al[10] reported that double balloon-occluded embolotherapy (DBOE) can lead to obliteration rectal varices. However, they have not stated whether contrast medium is stagnated in the varices as a result of occlusion of blood flow in the inferior mesenteric vein. In our case, since percutaneous transhepatic inferior mesenteric venography revealed that the blood of rectal varices was supplied by the inferior mesenteric vein only, we chose MPTO to treat the rectal varices, as it is an easier and less invasive procedure than DBOE. The total amount of sclerosant needed for MPTO or DBOE was 12 mL. If contrast medium stagnates in the rectal varices due to occlusion of the inferior mesenteric vein, as in our case, MPTO may be appropriate.

MPTO can also result in complications, such as renal failure causing hemoglobinuria because of hemolysis, and those associated with percutaneous transhepatic catheterization. Ohta et al[29] reported that intraperitoneal bleeding after retraction of the catheter is found in 10.6% patients with rectal varices. These complications can also be seen after DBOE. MPTO can close the in-flow and out-flow of rectal varices by occluding the blood flow of the inferior mesenteric vein.

In conclusion, MPTO with sclerosant may prove to be an extremely useful method in the treatment of rectal varices. Further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of this method.