Published online Aug 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5101

Revised: January 8, 2006

Accepted: January 14, 2006

Published online: August 28, 2006

Infection with H pylori is the most important known etiological factor associated with gastric cancer. While colonization of the gastric mucosa with H pylori results in active and chronic gastritis in virtually all individuals infected, the likelihood of developing gastric cancer depends on environmental, bacterial virulence and host specific factors. The majority of all gastric cancer cases are attributable to H pylori infection and therefore theoretically preventable. There is evidence from animal models that eradication of H pylori at an early time point can prevent gastric cancer development. However, randomized clinical trials exploring the prophylactic effect of H pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer in humans remain sparse and have yielded conflicting results. Better markers for the identification of patients at risk for H pylori induced gastric malignancy are needed to allow the development of a more efficient public eradication strategy. Meanwhile, screening and treatment of H pylori in first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients as well as certain high-risk populations might be beneficial.

- Citation: Trautmann K, Stolte M, Miehlke S. Eradication of H pylori for the prevention of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(32): 5101-5107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i32/5101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5101

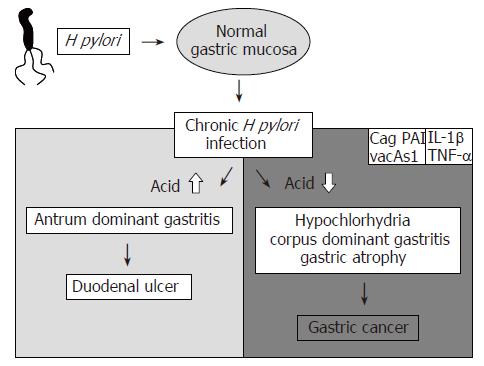

Despite decreasing incidence and mortality rates, gastric cancer remains the second most frequent malignancy worldwide, with the majority of cases diagnosed at an advanced stage[1]. A number of environmental factors, e.g. diets high in salt and N-nitrosamines and low in fruits and vegetables have been shown to contribute to gastric cancer development[2]. Furthermore, it is now well recognized that chronic infection with H pylori is tightly associated with the development of gastric cancer, primarily noncardiac gastric cancer. The clinical course of H pylori infection is highly variable and the likelihood of developing gastric cancer is determined by both microbial and host factors (Figure 1). Based on the large number of experimental and epidemiological studies, it seems reasonable to conclude that the eradication of H pylori should prevent gastric cancer. However, convincing results from clinical trials are not yet available. Hence, current clinical decision-making has to be based on indirect evidence: data from animal models and studies supporting the beneficial effect of eradication on the development of gastric cancer precursor lesions[3]. This article reviews the existing evidence that H pylori eradication prevents gastric cancer with a highlight on recent publications relevant for the clinician.

According to Correa’s model, gastric cancer development is a multistep process where the gastric mucosa is slowly transformed from normal epithelium to chronic gastritis, to multifocal atrophy, to intestinal metaplasia of various degrees, to dysplasia and finally to invasive cancer[4]. However, this sequence of events does not precede diffuse type gastric cancer and has even been debated for the intestinal type[5] since less than 10% of patients with these lesions ultimately develop gastric cancer[6]. Most H pylori infected individuals show antral predominant gastritis, which predisposes them to duodenal ulcers, but rarely causes gastric cancer. On the contrary, patients with corpus-predominant gastritis are likely to develop gastric ulcers, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and eventually gastric cancer. Our group, among others, has found that the pattern and the morphological distribution of gastritis correlate strongly with the gastric cancer risk[7,8]. We showed that the expression of H pylori associated gastritis in patients with gastric cancer is high in the corpus and is frequently associated with intestinal metaplasia and atrophy[9]. Based on these findings we developed a gastric carcinoma risk index, which evaluates grade and activity of corpus-dominant H pylori gastritis as well as the occurrence of intestinal metaplasia in the antrum or corpus to determine a patient’s risk for developing gastric carcinoma[10]. In a subsequent case control study, the gastric carcinoma risk index had a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 85% for diagnosing individuals with gastric carcinoma[11].

Infection with H pylori occurs worldwide, but the prevalence varies greatly among countries and among different populations within the same country[12]. The overall prevalence of H pylori infection is closely linked to current socioeconomic conditions[13]. Although the incidence of the infection in industrialized countries has decreased substantially over recent decades, it will remain endemic for at least another century, unless intervention occurs[14]. In the early 1990s a series of prospective case control studies[15-18] demonstrated a close link between H pylori infection and gastric cancer, which prompted the World Health Organization to announce the bacterium a class I (definite) carcinogen in 1994. Since then data from various studies have accumulated that further strengthen the association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer. One of the most compelling studies was conducted in Japan, where Uemura et al[19] prospectively followed 1526 patients over a period of 7.8 years. A total of 2.9 percent of H pylori infected individuals developed gastric cancer compared to none in the H pylori negative control group. Among individuals with H pylori infection, those with severe gastric atrophy (odds ratio: 4.9), corpus-predominant gastritis (odds ratio: 34.5) and intestinal metaplasia were at significantly higher risk for gastric cancer.

According to most retrospective, cohort and case control studies, the overall odds ratio for H pylori infection and gastric cancer is around two to six[19-23]. However, these numbers are likely to represent a gross underestimation of the real risk. Among the confounding factors that make risk appear lower in most studies are the long latency between the initiation of the carcinogenetic process and the clinical occurrence of cancer as well as the inclusion of individuals with antral predominant/duodenal ulcer phenotype[24]. If selection of patients and methodology is optimized, the odds ratio for H pylori infected individuals may increase to a factor of around 20[25-27].

H pylori displays a considerable amount of genetic variation. Even strains within an individual host commonly change over the course of the infection[28,29]. A number of bacterial virulence factors have been discovered that influence disease outcome in infected individuals. The majority of H pylori strains express and secrete VacA, a vacuolating cytotoxin, which is inserted into the gastric epithelial-cell and mitochondrial membranes, possibly providing the bacterium with nutrients and inducing apoptosis of the host cell[12,30]. VacA has also been found to modulate the host immune system via T-cell inhibition[31,32]. Studies indicate that expression of VacA increases bacterial fitness and in some western countries VacA s1 and VacA m1 genotypes are associated with more severe forms of gastritis, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and perhaps gastric cancer[33-36]. Another major focus of research is the analysis of the cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI), a genomic fragment comprising 31 genes that support the translocation of the 120-kD CagA protein into the gastric epithelial cell[37,38]. CagA has been shown to induce cytokine production along with a growth factor-like response in the host cell and to disrupt the junction-mediated gastric epithelial cell barrier function[39,40]. In western countries, patients carrying CagA+ H pylori strains are more likely to develop adenocarcinomas of the distal stomach than patients infected with CagA- strains[41]. In particular, one recent meta-analysis of case-control studies concluded that infection with CagA+ strains increases the risk over H pylori infection alone[42]. However, similar findings are not reported from Asia, where about 95% of all infected individuals carry CagA+ strains[3,43,44].

H pylori leads to inflammation of the gastric mucosa in virtually all infected individuals. However, most H pylori infected humans do not develop gastric cancer even if they are infected with so-called more virulent strains, indicating that host factors play a crucial role. The fact that first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients have a significantly increased risk for developing gastric cancer compared to patients without a family history further emphasizes the importance of genetic factors. For example, our group found some important gastric cancer related genes to be more prevalent in the gastric mucosa of first-degree relatives[45-49].

The infection with H pylori triggers an extensive systemic and local inflammatory response. Gastric epithelial cells respond by producing enhanced levels of interleukin-1β, interleukin-2, interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and tumor-necrosis-factor-α[50-52]. El-Omar and co-workers were the first to show that patients with certain Interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms, which lead to enhanced production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β are at increased risk for H pylori induced hypochlorhydria and gastric cancer[53]. Further studies found that proinflammatory polymorphisms of the IL-1 receptor antagonist, tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-10 are also associated with an increased risk for the development of noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma[54,55]. Interestingly, the combination of pro-inflammatory polymorphisms in the interleukin-1β gene and infection with more virulent

H pylori strains seems to increase the gastric cancer risk even more[56]. Most of the important studies exploring host genetics were performed in Caucasian populations and still need to be confirmed in other ethnic groups[3]. However, there is emerging evidence that similar associations can be found in Asian populations. For example, one study from Japan showed that proinflammatory IL-1β polymorphisms in H pylori infected Japanese individuals are significantly associated with hypochlorhydria and atrophic gastritis[57]. Recent data by Goto et al[58] also indicate that a common polymorphism in the coding gene for SHP-2 that interacts with the CagA protein can increase the risk for gastric atrophy in Japanese patients infected with CagA+ H pylori strains. The authors speculate that this might explain why only a proportion of CagA+ individuals develop gastric atrophy even though this strain is almost universal in Asian countries.

A number of animal models have been developed to study the mechanisms by which H pylori induces gastric carcinogenesis. Using the Mongolian gerbil model, several studies provided evidence that H pylori infection is in fact a potent carcinogen and able to induce gastric cancer by itself[59-62]. The studies by Watanabe et al[59] and Honda et al[60] found that 37% and 40% of infected animals developed well-differentiated intestinal adenocarcinomas 62 and 72 wk after inoculation of the bacterium. Both studies used cagA and vacA positive H pylori strains for infection of the animals. The risk of gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils increases significantly through combination of H pylori infection with other known carcinogens such as N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (NMU) and N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG)[63-65]. Studies using H pylori or H. felis infected mice found that the gastric cancer development is strongly determined by host specific factors, for example specific patterns of immune response. Some mouse strains develop a vigorous Th-1 response to the infection while others have a predominant Th-2 immune response and seem to be more resistant to mucosal damage. Those with the strong TH-1 response continue to develop atrophy, metaplasia and eventually invasive cancer in a gender specific manner[66].

There is evidence from animal models, that eradication of H pylori is able to prevent gastric carcinogenesis. The incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma in nitrosamine administered Mongolian gerbils with H pylori infection was significantly lower in animals receiving H pylori eradication[67,68]. Mouse models have also provided important evidence of beneficial effects from the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs, where atrophy and metaplasia have been reversed, in some cases completely[69].

Cure of H pylori infection results in several physiologic effects that are likely to reduce gastric cancer risk. These include reduction in cell turnover, elimination of DNA damage by a reduction of reactive oxygen species, increased gastric acid secretory capacity and restoration of ascorbic acid secretion into the gastric juice[1,70,71]. However, evidence from well-designed clinical studies supporting the cancer protective effect of H pylori eradication remains sparse (Table 1). Among the first clinical data to support the hypothesis that H pylori eradication is able to prevent gastric cancer development were case-control studies from Sweden on patients undergoing hip replacement procedures. Akre et al[72] showed that significantly reduced rates of gastric cancer occurred in such patients who frequently receive high doses of prophylactic antibiotics, incidentally eradicating H pylori infection. As discussed earlier in this review, the study by Uemura et al[19] provides some of the strongest evidence for the causative role of H pylori infection in gastric cancer development. Here, gastric cancer developed in 2.9% of all H pylori infected patients compared with 0% of those without infection. Notably, no case of cancer developed in a subgroup of 253 H pylori infected patients who received eradication therapy at an early time point after enrollment in the study. The same group of investigators found that eradication of H pylori was able to prevent relapse after endoscopic resection of early stage gastric cancer[73]. Another study by Saito et al[74] showed that H pylori eradication had a favorable impact on gastric cancer development in patients with gastric adenoma. More recently, Take et al[75] published the results from a large prospective Japanese intervention trial. The authors endoscopically followed 1342 patients with peptic ulcer disease for a mean period of 3.4 years. All patients initially received H pylori eradication therapy. The risk of developing gastric cancer was significantly higher in the group of patients who failed eradication therapy compared to those who were cured for the infection.

| Study | Design | Follow-up | Patients | Treatment | Outcome |

| Uemura et al 1997 | Nonrandomized intervention trial | 2 yr | 132 Japanese patients with endoscopically removed early stage gastric cancer and H pylori infection | H pylori eradication therapy or no treatment | Reduced rate of gastric cancer development after eradication of H pylori |

| Saito et al 2000 | Nonrandomized intervention trial | 2 yr | 64 Japanese patients with gastric adenoma and Hpylori infection | H pylori eradication therapy or no treatment | Reduced rate of metachronous gastric cancer development after eradication of H pylori |

| Correa et al 2000 | Prospective, randomized, placebo controlled trial | 6 yr | 852 individuals from a high risk region in Colombia with H pylori infection and precancerous lesions | H pylori eradication therapy and/or ascorbic acid/beta-carotene or placebo | Significant increase in the rate of regression of precursor conditions after cure of H pylori and/or treatment with dietary supplements |

| Wong et al 2004 | Prospective, randomized, placebo controlled trial | 8 yr | 1630 individuals from a high risk region in China with H pylori infection; with or without precancerous lesions | H pylori eradication therapy or placebo | Significant reduction in gastric cancer risk after cure of H pylori only for patients without precancerous conditions |

| Take et al 2005 | Nonrandomized intervention trial | 3.4 yr | 1342 Japanese patients with peptic ulcer disease | H pylori eradication therapy | Significant increase in gastric cancer risk for patients with persistent H pylori infection |

The first prospective randomized controlled study to examine the effect of H pylori eradication on gastric cancer development was published by Wong et al[76] in 2004. The authors randomized 1630 individuals from a high-risk region in China with confirmed H pylori infection to eradication therapy or placebo. After a follow-up period of 7.5 years, they found no difference in gastric cancer incidence between those receiving H pylori eradication therapy and those who were not given treatment (7 vs 11 cases, P = 0.33). However, further subgroup analysis of the data demonstrated a significant benefit (P = 0.02) from eradication therapy in patients without baseline intestinal metaplasia at the time of study enrollment.

Unfortunately, several international prospective randomized controlled trials, designed to evaluate the long-term effect of H pylori eradication on gastric cancer development had to be abandoned. For example, the PRISMA study[77], initiated in 1998 by our group to test the effect of H pylori eradication therapy in a high-risk population in Germany and Austria was discontinued due to insufficient recruiting. As might be expected, most eligible patients for those studies are not willing to enter the placebo arm after the nature of such a trial has been explained to them. Apart from ethical issues, the required follow-up time of 10 to 20 years for these trials remains an additional problem. A growing number of studies are therefore using surrogate markers for gastric cancer development, namely gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia as primary study endpoints.

There is consistent evidence that H pylori eradication cures gastritis and numerous studies have shown that atrophy and metaplasia do not progress in patients after H pylori eradication compared to control groups who remain H pylori positive[78-86]. However, many of the available studies addressing the reversibility of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia have yielded conflicting and inconsistent results, possibly because most of them are nonrandomized, not controlled, have short follow-up periods and only include small numbers of patients[1,3]. One of the few randomized controlled trials for the prevention of gastric dysplasia was conducted by Correa et al[87] in 2000. The authors found significant regression of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia after H pylori eradication alone and in combination with β-carotene and ascorbic acid. Sung et al[88] prospectively followed a total of 587 H pylori infected patients, randomized to receive either eradication therapy or placebo, endoscopically for one year. Decrease in acute and chronic gastritis was significantly more frequent after H pylori eradication, but after the relatively short follow-up period, changes in intestinal metaplasia were similar between the two groups. The majority of available studies suggest, however, that regression of atrophic gastritis and, to a lesser extent, intestinal metaplasia can occur at least in a subset of patients with sufficient follow-up[3,89].

In conclusion, there is little randomized controlled trial evidence to suggest that H pylori eradication decreases the risk of gastric cancer development. However, regression of gastric cancer precursor lesions may occur in some patients. At present, there are no markers that help to predict such a response in the individual patient. Therefore, eradication at the earliest possible time point in the disease process seems favorable. The optimal age for testing of H pylori infection still needs to be determined but available data suggest that eradication at a younger age might be a more favorable approach. Future research has to focus on identification of host and bacterial specific markers that will help to predict the development of gastric cancer in the H pylori infected individuals. Better identification of individuals at high risk for gastric cancer will allow for more effective prevention and eradication strategies. Meanwhile, screening and treatment of H pylori in first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients as well as certain high-risk populations might be beneficial.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Hunt RH. Will eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection influence the risk of gastric cancer. Am J Med. 2004;117 Suppl 5A:86S-91S. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ngoan LT, Mizoue T, Fujino Y, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Dietary factors and stomach cancer mortality. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Malfertheiner P, Sipponen P, Naumann M, Moayyedi P, Mégraud F, Xiao SD, Sugano K, Nyrén O. Helicobacter pylori eradication has the potential to prevent gastric cancer: a state-of-the-art critique. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2100-2115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Meining A, Morgner A, Miehlke S, Bayerdörffer E, Stolte M. Atrophy-metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence in the stomach: a reality or merely an hypothesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:983-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nardone G, Morgner A. Helicobacter pylori and gastric malignancies. Helicobacter. 2003;8 Suppl 1:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miehlke S, Hackelsberger A, Meining A, Hatz R, Lehn N, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Severe expression of corpus gastritis is characteristic in gastric cancer patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miehlke S, Hackelsberger A, Meining A, von Arnim U, Müller P, Ochsenkühn T, Lehn N, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Histological diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori gastritis is predictive of a high risk of gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:837-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Meining A, Stolte M, Hatz R, Lehn N, Miehlke S, Morgner A, Bayerdörffer E. Differing degree and distribution of gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases. Virchows Arch. 1997;431:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Meining A, Bayerdörffer E, Müller P, Miehlke S, Lehn N, Hölzel D, Hatz R, Stolte M. Gastric carcinoma risk index in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:311-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Meining A, Kompisch A, Stolte M. Comparative classification and grading of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in patients with gastric cancer and patients with functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:707-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 1905] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Malaty HM, Graham DY. Importance of childhood socioeconomic status on the current prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1994;35:742-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rupnow MF, Shachter RD, Owens DK, Parsonnet J. A dynamic transmission model for predicting trends in Helicobacter pylori and associated diseases in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:228-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Epidemiology of, and risk factors for, Helicobacter pylori infection among 3194 asymptomatic subjects in 17 populations. The EUROGAST Study Group. Gut. 1993;34:1672-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, Yarnell JW, Stacey AR, Wald N, Sitas F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991;302:1302-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2805] [Cited by in RCA: 2738] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1302] [Cited by in RCA: 1234] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3179] [Article Influence: 132.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet. 1993;341:1359-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 842] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2373-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in RCA: 749] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Genta RM. Screening for gastric cancer: does it make sense. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 2:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nardone G, Rocco A, Malfertheiner P. Review article: helicobacter pylori and molecular events in precancerous gastric lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ekström AM, Held M, Hansson LE, Engstrand L, Nyrén O. Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer established by CagA immunoblot as a marker of past infection. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:784-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brenner H, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Rothenbacher D. Is Helicobacter pylori infection a necessary condition for noncardia gastric cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:252-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Falush D, Kraft C, Taylor NS, Correa P, Fox JG, Achtman M, Suerbaum S. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15056-15061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Suerbaum S, Smith JM, Bapumia K, Morelli G, Smith NH, Kunstmann E, Dyrek I, Achtman M. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12619-12624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Szabò I, Brutsche S, Tombola F, Moschioni M, Satin B, Telford JL, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Papini E, Zoratti M. Formation of anion-selective channels in the cell plasma membrane by the toxin VacA of Helicobacter pylori is required for its biological activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:5517-5527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Boncristiano M, Paccani SR, Barone S, Ulivieri C, Patrussi L, Ilver D, Amedei A, D'Elios MM, Telford JL, Baldari CT. The Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin inhibits T cell activation by two independent mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1887-1897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Montecucco C, de Bernard M. Immunosuppressive and proinflammatory activities of the VacA toxin of Helicobacter pylori. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1767-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Crowe SE. Helicobacter infection, chronic inflammation, and the development of malignancy. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:32-38. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Agha-Amiri K, Günther T, Lehn N, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M, Ehninger G, Bayerdörffer E. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA is associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Miehlke S, Yu J, Schuppler M, Frings C, Kirsch C, Negraszus N, Morgner A, Stolte M, Ehninger G, Bayerdörffer E. Helicobacter pylori vacA, iceA, and cagA status and pattern of gastritis in patients with malignant and benign gastroduodenal disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1008-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Atherton JC, Peek RM Jr, Tham KT, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:92-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 954] [Cited by in RCA: 965] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648-14653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1375] [Cited by in RCA: 1392] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science. 2003;300:1430-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 755] [Cited by in RCA: 782] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Wu AH, Crabtree JE, Bernstein L, Hawtin P, Cockburn M, Tseng CC, Forman D. Role of Helicobacter pylori CagA+ strains and risk of adenocarcinoma of the stomach and esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:815-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Maeda S, Kanai F, Ogura K, Yoshida H, Ikenoue T, Takahashi M, Kawabe T, Shiratori Y, Omata M. High seropositivity of anti-CagA antibody in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients irrelevant to peptic ulcers and normal mucosa in Japan. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1841-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Pan ZJ, van der Hulst RW, Feller M, Xiao SD, Tytgat GN, Dankert J, van der Ende A. Equally high prevalences of infection with cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients with peptic ulcer disease and those with chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1344-1347. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Miehlke S, Yu J, Ebert M, Szokodi D, Vieth M, Kuhlisch E, Buchcik R, Schimmin W, Wehrmann U, Malfertheiner P. Expression of G1 phase cyclins in human gastric cancer and gastric mucosa of first-degree relatives. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1248-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ebert MP, Yu J, Miehlke S, Fei G, Lendeckel U, Ridwelski K, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Malfertheiner P. Expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 in gastric cancer and in the gastric mucosa of first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1795-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yu J, Ebert MP, Miehlke S, Rost H, Lendeckel U, Leodolter A, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Malfertheiner P. alpha-catenin expression is decreased in human gastric cancers and in the gastric mucosa of first degree relatives. Gut. 2000;46:639-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ebert MP, Günther T, Hoffmann J, Yu J, Miehlke S, Schulz HU, Roessner A, Korc M, Malfertheiner P. Expression of metallothionein II in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1995-2001. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Yu J, Miehlke S, Ebert MP, Hoffmann J, Breidert M, Alpen B, Starzynska T, Stolte Prof M, Malfertheiner P, Bayerdörffer E. Frequency of TPR-MET rearrangement in patients with gastric carcinoma and in first-degree relatives. Cancer. 2000;88:1801-1806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Kashima K, Imanishi J. Induction of various cytokines and development of severe mucosal inflammation by cagA gene positive Helicobacter pylori strains. Gut. 1997;41:442-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Imanishi J. Helicobacter pylori cagA gene and expression of cytokine messenger RNA in gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1744-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Crabtree JE, Wyatt JI, Trejdosiewicz LK, Peichl P, Nichols PH, Ramsay N, Primrose JN, Lindley IJ. Interleukin-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori infected, normal, and neoplastic gastroduodenal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:61-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1690] [Cited by in RCA: 1673] [Article Influence: 66.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | El-Omar EM, Rabkin CS, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Schoenberg JB, Stanford JL, Mayne ST, Goedert J, Blot WJ. Increased risk of noncardia gastric cancer associated with proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1193-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 676] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Machado JC, Pharoah P, Sousa S, Carvalho R, Oliveira C, Figueiredo C, Amorim A, Seruca R, Caldas C, Carneiro F. Interleukin 1B and interleukin 1RN polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of gastric carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Figueiredo C, Machado JC, Pharoah P, Seruca R, Sousa S, Carvalho R, Capelinha AF, Quint W, Caldas C, van Doorn LJ. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin 1 genotyping: an opportunity to identify high-risk individuals for gastric carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1680-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Furuta T, El-Omar EM, Xiao F, Shirai N, Takashima M, Sugimura H. Interleukin 1beta polymorphisms increase risk of hypochlorhydria and atrophic gastritis and reduce risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:92-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Goto Y, Ando T, Yamamoto K, Tamakoshi A, El-Omar E, Goto H, Hamajima N. Association between serum pepsinogens and polymorphismof PTPN11 encoding SHP-2 among Helicobacter pylori seropositive Japanese. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, Satoh R, Nishizono A, Nasu M. Development of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4255-4259. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Hirayama F, Takagi S, Iwao E, Yokoyama Y, Haga K, Hanada S. Development of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and carcinoid due to long-term Helicobacter pylori colonization in Mongolian gerbils. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:450-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Zheng Q, Chen XY, Shi Y, Xiao SD. Development of gastric adenocarcinoma in Mongolian gerbils after long-term infection with Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1192-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Sugiyama A, Maruta F, Ikeno T, Ishida K, Kawasaki S, Katsuyama T, Shimizu N, Tatematsu M. Helicobacter pylori infection enhances N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced stomach carcinogenesis in the Mongolian gerbil. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2067-2069. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Tokieda M, Honda S, Fujioka T, Nasu M. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on the N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced gastric carcinogenesis in mongolian gerbils. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1261-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Shimizu N, Inada K, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto T, Ikehara Y, Kaminishi M, Kuramoto S, Sugiyama A, Katsuyama T, Tatematsu M. Helicobacter pylori infection enhances glandular stomach carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils treated with chemical carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fox JG, Rogers AB, Ihrig M, Taylor NS, Whary MT, Dockray G, Varro A, Wang TC. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric cancer in INS-GAS mice is gender specific. Cancer Res. 2003;63:942-950. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inada K, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto T, Nozaki K, Kaminishi M, Kuramoto S, Sugiyama A, Katsuyama T. Eradication diminishes enhancing effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on glandular stomach carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1512-1514. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inoue M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K, Tanaka H, Kumagai T, Kaminishi M, Tatematsu M. Effect of early eradication on Helicobacter pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Hahm KB, Song YJ, Oh TY, Lee JS, Surh YJ, Kim YB, Yoo BM, Kim JH, Han SU, Nahm KT. Chemoprevention of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis in a mouse model: is it possible. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;36:82-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Forbes GM, Warren JR, Glaser ME, Cullen DJ, Marshall BJ, Collins BJ. Long-term follow-up of gastric histology after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:670-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Haruma K, Mihara M, Okamoto E, Kusunoki H, Hananoki M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases gastric acidity in patients with atrophic gastritis of the corpus-evaluation of 24-h pH monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Akre K, Signorello LB, Engstrand L, Bergström R, Larsson S, Eriksson BI, Nyrén O. Risk for gastric cancer after antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing hip replacement. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6376-6380. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639-642. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Saito K, Arai K, Mori M, Kobayashi R, Ohki I. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on malignant transformation of gastric adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Oguma K, Okada H, Shiratori Y. The effect of eradicating helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1037-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1044] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Dragosics B, Gschwantler M, Oberhuber G, Antos D, Dite P, Läuter J, Labenz J, Leodolter A. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: current status of the Austrain Czech German gastric cancer prevention trial (PRISMA Study). World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:243-247. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Moayyedi P, Wason C, Peacock R, Walan A, Bardhan K, Axon AT, Dixon MF. Changing patterns of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in long-standing acid suppression. Helicobacter. 2000;5:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Annibale B, Di Giulio E, Caruana P, Lahner E, Capurso G, Bordi C, Delle Fave G. The long-term effects of cure of Helicobacter pylori infection on patients with atrophic body gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1723-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Ito M, Haruma K, Kamada T, Mihara M, Kim S, Kitadai Y, Sumii M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy improves atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: a 5-year prospective study of patients with atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1449-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Kim N, Lim SH, Lee KH, Choi SE, Jung HC, Song IS, Kim CY. Long-term effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on intestinal metaplasia in patients with duodenal and benign gastric ulcers. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1754-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Kokkola A, Sipponen P, Rautelin H, Härkönen M, Kosunen TU, Haapiainen R, Puolakkainen P. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the natural course of atrophic gastritis with dysplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:515-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Kyzekova J, Mour J. The effect of eradication therapy on histological changes in the gastric mucosa in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori infection. Prospective randomized intervention study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2048-2056. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Stolte M, Meining A, Koop H, Seifert E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori heals atrophic corpus gastritis caused by long-term treatment with omeprazole. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:91-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Ohkusa T, Fujiki K, Takashimizu I, Kumagai J, Tanizawa T, Eishi Y, Yokoyama T, Watanabe M. Improvement in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in patients in whom Helicobacter pylori was eradicated. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Müller H, Rappel S, Wündisch T, Bayerdörffer E, Stolte M. Healing of active, non-atrophic autoimmune gastritis by H. pylori eradication. Digestion. 2001;64:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881-1888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Sung JJ, Lin SR, Ching JY, Zhou LY, To KF, Wang RT, Leung WK, Ng EK, Lau JY, Lee YT. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia one year after cure of H. pylori infection: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Walker MM. Is intestinal metaplasia of the stomach reversible. Gut. 2003;52:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |