INTRODUCTION

Pseudoachalasia is a disease entity usually associated with tumors causing obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction and producing abnormal esophageal motility mimicking an idiopathic achalasia[1]. Idiopathic achalasia is a motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by aperistalsis and failure of the lower esophageal relaxation, resulting in symptoms such as dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain and weight loss. The pathogenesis of idiopathic achalasia is due to the selective loss of inhibitory neuron of the myenteric plexus which produces vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), nitric oxide and inflammatory infiltration and is responsible for the unopposed excitation of lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[2-4], thereby causing dysfunction or failure of the LES relaxation in response to each swallow[4,5]. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia is different from idiopathic achalasia. In pseudoachalasia, the proposed pathogenesis is considered as a mechanical obstruction of the distal esophagus or an infiltration of the malignancy that affects the inhibitory neurons of the meyenteric plexus. Endoscopy and radiologic tests are often important in distinguishing between them, although the eventual diagnosis is made only by surgical explorations in the most cases. These both types of achalasia share the same manometric phenomenon of aperistalsis of the esophageal body and incomplete LES relaxation. However, one report suggested that patients with achalasia have autonomic nerve dysfunction in the vagal nerve outside the esophagus[6]. Trauma to the gastroesophageal junction may potentially damage the vagus nerve, thereby leading to secondary achalasia. Most case reports on pseudoachalasia were tumor related, but implicated vagal nerve injury following surgery as a cause of achalasia[8-10] still occurred. We report herein a reversible pseudoachalasia following the truncal vagotomy for pyloric obstruction, which was successfully treated by pneumatic dilations.

CASE REPORT

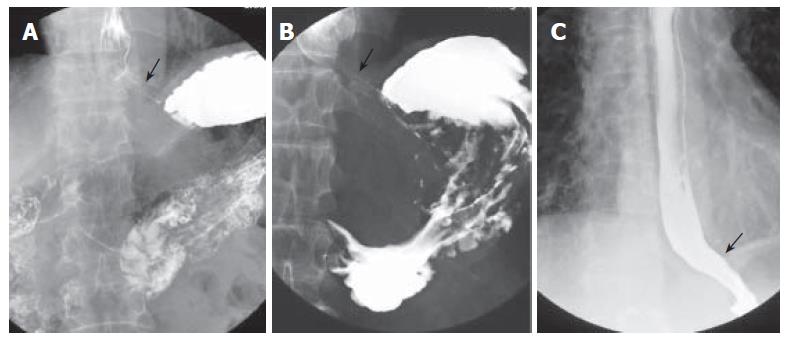

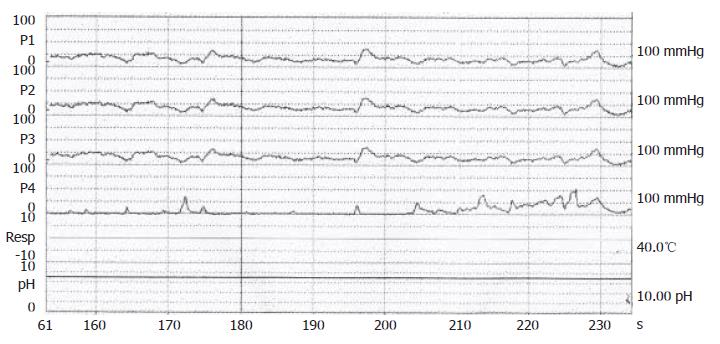

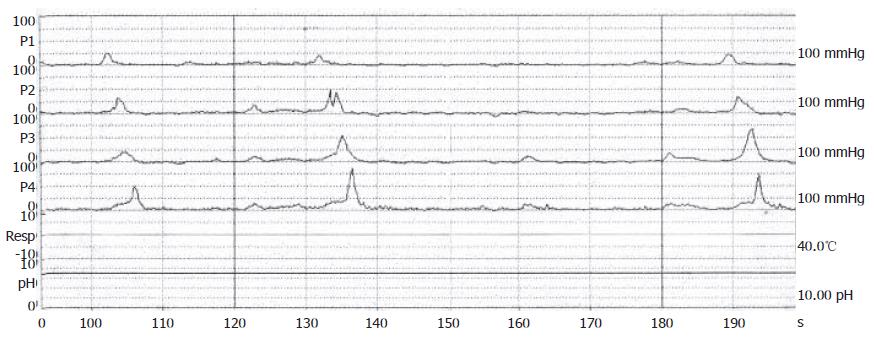

A 70-year-old male, suffered from repeated peptic ulcer bleeding for at least 10 years, developed progressive symptoms of post-prandial vomiting in October 1996. A barium esophagogram and upper gastrointestinal series demonstrated an intact gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1A) and good esophageal peristalsis, but deformed gastric antrum and a deep ulceration. Malignancy was excluded by endoscopy biopsy. Under the condition of pyloric obstruction, he received a truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty surgery. The month following surgery, the patient developed dysphagia, regurgitation of food. Endoscopy revealed food retention in the esophageal lumen and a tight gastroesophageal junction, thereby suggesting an achalasia. Barium esophagography showed a dilated distal esophageal lumen with food retention and narrowing of gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1B). Achalasia was confirmed using manometric findings of esophageal aperistalsis and incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during wet swallowing (Figure 2). Although the residual pressure was about 12 mmHg but the basal LES pressure was only about 25 mmHg. Achalasia caused by tumors was excluded by computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography. The patient received two episodes of pneumatic dilatation. The symptoms gradually resolved within 4 mo after dilatation and the manometric studies showed restoration of esophageal peristalsis and normal swallowing relaxation (Figure 3). Barium esophagography showed a non-dilated esophageal lumen with smooth passage of contrast medium through gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1C). After nine years, the patient still remains symptom-free with a normal esophageal motility studies.

Figure 1 A: Barium esophagography and upper gastrointestinal series showing an intact gastroesophageal junction; B: dilated distal esophageal lumen with food retention and narrowing of gastroesophageal junction after truncal vagotomy; C: barium esophagography showing a non-dilated esophageal lumen with smooth passage of contrast medium through gastroesophageal junction after pneumodilations.

Figure 2 Confirmation of achalasia by manometric findings of esophageal aperistalsis and incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during wet swallowing.

Figure 3 Manomteric studies showing restoration of esophageal motility with normal peristalsis as a healthy subject after dilations.

DISCUSSION

Pseudoachalasia or secondary achalasia is a motility disorder of the esophagus, and usually cannot be distinguished from primary achalasia[1]. Approximately 2-4% of achalasia patients who fulfill the manometric criteria may develop in a malignant disease[11]. The clinical spectrum of psudoachalasia is almost the same as idiopathic achalasia; both have progressive dysphagia, retrosternal pain, food regurgitation and weight loss. While the radiological findings show a dilated esophagus with ”beak-like” distal end, there is aperistalsis of the esophageal body with an incomplete or non-relaxing lower esophageal sphincter on manometry studies in both groups of patients. Therefore, it is difficult for the clinician to distinguish pseudoachalasia from idiopathic achalasia. Pseudoachalasia has many etiologies, including tumor. Most of the patients with pseudoachalasia reported in the literature suffered from a primary or metastatic malignancy around the esophagogastric junction. Some are from benign diseases, such as pancreatic pseudocysts, mesenchymal tumors of the esophagus and mediastinal fibrosis[11-15]. In rare instances, pseudoachalasia may be a complication of various surgeries, the majority being anti-reflux procedures, gastric banding and gastrectomy[9,16,17]. Our case resulted as a complication from truncal vagotomy for pyloric obstrction.

The mechanisms of esophageal motor dysfunction in pseudoachalasia have been proposed as follows[17]: (1) circumferential obstruction of the lower esophagus and/or LES; (2) infiltration of inhibitory neurons of the esophageal myenteric plexus by tumor cells; (3) neuronal degeneration distant from the primary tumor site with reduction in ganglion cells in the dorsal nucleus of the vagal nerve or in the vagal nerve itself; and (4) an interaction of tumor factors with the esophageal neuronal plexus without a direct infiltration of the esophagogastric junction (paraneoplastic).

Achalasia has been described following fundoplication and was attributed to vagal nerve damage during surgery[18]. In patients who are found to have an achalasia-type motor dysfunction following anti-reflux surgery, Poulin et al[7] suggested three additional explanations. In type 1, primary achalasia had been misdiagnosed, and dysphagia became obvious only after surgery. An alternative explanation for this type of achalasia may be the assumption of Spechler et al[19] that achalasia may occasionally develop from underlying gastroesophageal reflux disease. Type 2 may be due to extensive development of scar tissue and/or an overly tight fundic wrap. In most instances, the motor abnormality disappears following dilation therapy or reconstruction of the fundoplication, as in our patient. Finally, in type 3, achalasia follows anti-reflux surgery after a more prolonged interval. In contrast to type 2, there is no stenosis or fibrosis of the esophagus or the periesophageal tissue, and myotomy is always an effective therapeutic strategy.

Shah et al[20] reported that 25% of patients diagnosed with achalasia had a history of operative or non-operative trauma to the chest and/or upper gastrointestinal tract, compared with 9.5% of patients with dysphagia and normal manometry, thereby suggesting that, in some cases, operative and non-operative trauma may result in vagal disruption and lead to neuropathic dysfunction with the resultant development of achalasia[20]. The mechanism of damage may not be the same as vagal transaction. Vagal efferent fibers, with their cell bodies in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, have a crucial role in initiating and modulating esophageal peristalsis and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Pathological analyses of operative and postmortem specimens from patients with achalasia have demonstrated abnormalities of both extrinsic and intrinsic innervations of the esophagus and LES. The majority of studies revealed a loss of ganglion cells from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and demyelination of the vagal afferent fibers suggesting denervation[21,22].

Neural control of the LES includes cholinergic and noncholinergic (or nonadrenergic) inhibitory pathways involving the presentation of nitric oxide, acetylcholine, and VIP. Nitric oxide plays an important role in mediating LES relaxation. Nitrergic neurons are present in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, as the source of preganglionic motor neurons to the LES[23]. Experimental inhibition of nitric oxide may produce a picture mimicking achalasia on manometry. An alternative explanation for post-traumatic achalasia may involve nitrergic pathways. By some mechanisms, trauma may impair the generation of nitric oxide, resulting in decreased inhibition of the lower esophageal sphincter and an abnormality in sequential relaxation of the body of the esophagus[24].

Pneumatic dilation provides a safe, effective and relatively inexpensive option for achalasia treatment[25,26]. The major adverse event caused by pneumatic dilations is esophageal perforation, with a 2%-6% cumulative rate[25-27]. Less common complications are intramural hematoma, diverticula at gastric cardia, mucosal tears, reflux esophagitis, prolonged post-procedure chest pain, hematemesis without change in hematocrit, fever and angina[25,26,28]. Pneumatic dilation for a malignancy-induced pseudoachalasia stenosis not only provides an ineffective treatment, but also delays adequate therapy of the underlying disorder. Surgery is the best treatment modality but the use of metallic stents is another therapeutic option for the unresectable ones[29].However, pneumatic dilation may improve the pseudoachalasia caused by benign etiology and may provide a complete recovery from stenosis as in our patient.

In summary, implicated vagal nerve injury following surgery can cause pseudoachalasia. The motor normality usually resolved following a therapeutic procedure, such as pneumatic dilation on the gastroesophageal junction. Further studies on comparing esophageal manometry and vagal integrity before and after surgery are required.