Published online Aug 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5028

Revised: March 18, 2006

Accepted: March 27, 2006

Published online: August 21, 2006

AIM: To describe the trend in duodenal biopsy performance during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in an adult Spanish population, and to analyze its value for the diagnosis of celiac disease in clinical practice.

METHODS: A 15 year-trend (1990 to 2004) in duo-denal biopsy performed when undertaking upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was studied. We analysed the prevalence of celiac disease in the overall group, and in the subgroups with anaemia and/or chronic diarrhoea.

RESULTS: Duodenal biopsy was performed in 1033 of 13 678 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies (7.6%); an increase in the use of such was observed over the study period (1.9% in 1990-1994, 5% in 1995-1999 and 12.8% in 2000-2004). Celiac disease was diagnosed in 22 patients (2.2%), this being more frequent in women than in men (3% and 1% respectively). Fourteen out of 514 (2.7%) patients with anaemia, 12 out of 141 (8.5%) with chronic diarrhoea and 8 out of 42 (19%) with anaemia plus chronic diarrhoea had celiac disease. A classical clinical presentation was observed in 55% of the cases, 23% of the patients had associated dermatitis herpetiformis and 64% presented anaemia; 9% were diagnosed by familial screening and 5% by cryptogenetic hypertransaminasaemia.

CONCLUSION: Duodenal biopsy undertaken during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in adults, has been gradually incorporated into clinical practice, and is a useful tool for the diagnosis of celiac disease in high risk groups such as those with anaemia and/or chronic diarrhoea.

- Citation: Riestra S, Domínguez F, Fernández-Ruiz E, García-Riesco E, Nieto R, Fernández E, Rodrigo L. Usefulness of duodenal biopsy during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for diagnosis of celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(31): 5028-5032

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i31/5028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5028

Celiac disease (CD) is a frequent immune-mediated enteropathy of worldwide distribution. It affects both children and adults and has a heterogeneous clinical presentation[1]. Even though we currently possess sensitive and specific serological methods, the duodenal biopsy continues to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of CD[2]. Knowledge of the diverse forms of presentation of CD, together with a high index of clinical suspicion and an improvement in the accessibility to endoscopy units have made it possible, in some geographical areas, that the number of diagnosed celiac patients approximates the number of patients estimated from population screening studies[3].

Endoscopic duodenal biopsy is a diagnostic tool in the management of patients with chronic diarrhoea and ferropenic anemia[4,5], these being frequent manifestations of CD[1]. Several studies have been designed in order to know the prevalence of CD among those with anemia or diarrhoea[6-13]. However, the usefulness of duodenal biopsy during upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy for diagnosis of CD is less well known in daily clinical practice[14].

In Spain, the prevalence of CD in the general population is similar to other European countries (1/118 to 1/389)[15-17], we do not however possess data on the performance of duodenal biopsy in adults in clinical practice. The aims of the present study were to obtain information on the evolution of the practice of duodenal biopsy in adults over a 15-year period in a Spanish Digestive Endoscopy Unit and also to study the efficacy of such for the diagnosis of CD in high risk groups of patients, such as those with anemia and/or chronic diarrhoea. The clinical characteristics of celiac patients diagnosed throughout the study are also described.

The Gastroenterology Unit of Hospital Valle del Nalón (Asturias, Northern Spain) is the reference for an adult population of 75 212 people (27% > 60 years). All upper GI endoscopies were performed by three gastroenterologists (RS, F-RE and NR) and duodenal biopsies (3-5 samples per patient) were evaluated by the same pathologist (DF). A special interest in CD began in 1997, when an epidemiological study was undertaken on the prevalence of the disease in the general population of this area[15]. In clinical practice, the access to Digestive Endoscopy Unit is not open to primary care and serological testing for CD has always been available (antigliadine, antiendomysium and/or antitransglutaminase, according to the period analysed). From 1998, the genetic study of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 has also been available.

Using the computerized register of all upper GI endoscopies performed between 1990 and 2004 (13 678), we created a database of all patients who had undergone a duodenal biopsy (1033). After excluding 12 explorations in which it was not possible to reach a histological diagnosis due to technical problems and another 12 which were performed in already known celiacs, the total sample analysed was 1009 explorations. The variables included for study are as follows: year when duodenal biopsy was undertaken, age and gender of patient, indication for upper GI endoscopy and the final histological diagnosis.

We studied the evolution over time of the performance of duodenal biopsy during the upper GI endoscopies; in some cases the endoscopic exploration was made exclusively in order to perform duodenal biopsies, since a high index of suspicion of CD previously existed (for example, positive serology or malabsorption syndrome). However, in the majority of the cases, it was the endoscopist who decided, at the time of exploration, whether or not to take duodenal biopsies, when faced with the finding of anomalies in the intestinal mucosa or the presence of certain symptoms or analytical changes (diarrhoea, anemia, iron deficiency, etc).

We analysed those cases diagnosed as celiacs; the enteropathy was described according to the Marsh´ classification (modified by Oberhuer)[18] and a response to a gluten-free diet, was used as the diagnostic criteria for CD. We studied the frequency of CD, according to the main indication for performing the duodenal biopsy. The subgroup of patients with anemia (n = 514) included those in which the indication for endoscopic study was the presence of ferropenic anemia, microcytic anemia or iron and/or folic acid deficiency; patients with anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency or those in whom the anemia was associated with signs or symptoms of upper GI bleeding, were excluded from the analysis. The subgroup of patients with diarrhoea (n = 141) included those with a picture of chronic diarrhoea (> 4 wk) in whom a possible origin was suspected in the small intestine.

The clinical, serological and genetic characteristics of patients diagnosed with CD over the study period are presented in this paper.

Data are expressed as percentages or absolute number for categorical variables and medians and ranges for continuous variables. The Chi-square test was used to test for differences between groups of patients with regard to their clinical and demographic features. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to describe the independent association of variables, and the output was converted into adjusted likelihood ratios. A stepwise (forward) selection procedure was employed in order to prevent exclusion of important variables from the model, as a result of mutual correlations. The covariables introduced in the model were age, gender, anemia, diarrhoea, and year of performance of duodenal biopsy (stratified into three periods). The relationship between CD and the above variables was quantified as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals are provided. All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc®, Ver. 7.4.4.1 (MedCalc Software). A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

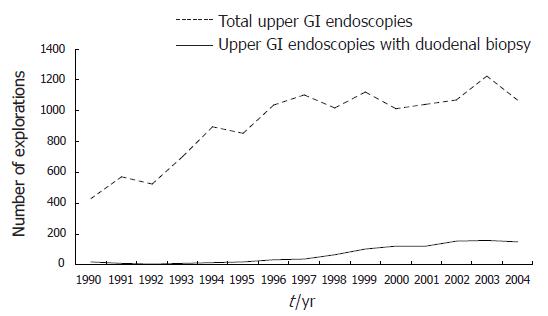

From 1990 to 2004, duodenal biopsy was performed in 1033 out of a total of 13 678 upper GI endoscopies (7.4%). Figure 1 represents the 15-year evolution of the performance of duodenal biopsy in the final sample evaluated (1009); when a division was made into three consecutive periods of five years: 1990-1994, 1995-1999 and 2000-2004, we found a significant increase in the percentage of endoscopic explorations in which duodenal biopsy was performed: 58 out of 3121 (1.9%) in the first period, 258 out of 5128 (5%) in the second period, and 693 out of 5405 (12.8%) in the third (1.9% vs 5%, P < 0.0001; 5% vs 12.8%, P < 0.001).

Up to 1997 a duodenal biopsy was not indicated by positive serology for CD and up to 1999, this was not made in first-degree relatives of celiac patients. Duodenal biopsy was performed in 7.7% of the patients with anemia as the main indication for upper GI endoscopy during the first period, in 21% during the second, and in 73% during the third period.

The total group included 600 females and 409 males with a median age of 60 years (range 14-93 years), without significant differences in gender. Twenty two patients were diagnosed with CD, which accounted for 2.2% of the duodenal biopsies performed; in 6 subjects (27%) the duodenal biopsy was indicated after knowing the presence of positive serology for CD, while in the 16 remaining patients (73%), this was performed according to the clinical suspicion of CD (based on the presence of chronic diarrhoea, non-specific digestive symptoms, etc) or by the finding of persistent analytical changes (anemia and/or iron deficiency). The prevalence of CD in the overall group and also in the subgroups of anemia and/or chronic diarrhoea is shown in Table 1.

| Number | CD n (%) | 95% CI | |

| Study population | 1009 | 22 (2.2) | 1.4-3.3 |

| Period: | |||

| 1990-1994 | 58 | 2 (3.4) | 0.6-13.0 |

| 1995-1999 | 258 | 8 (3.1) | 1.5-6.3 |

| 2000-2004 | 693 | 12 (1.7) | 0.9-3.1 |

| Gender: | |||

| Female | 600 | 18 (3) | 1.8-4.8 |

| Male | 409 | 4 (1) | 0.3-2.7 |

| Age (yr): | |||

| 14-34 | 136 | 3 (2.2) | 0.6-6.8 |

| 35-54 | 309 | 11 (3.6)b | 1.9-6.5 |

| 55-74 | 365 | 7 (1.9) | 0.8-4.1 |

| ≥ 75 | 199 | 1 (0.5) | 0.03-3.2 |

| Patient subgroups: | |||

| Anemia | 514 | 14 (2.7) | 1.6-4.6 |

| Diarrhoea | 141 | 12 (8.5)d | 4.7-14.7 |

| Anemia plus diarrhoea | 42 | 8 (19)f | 9.1-34.6 |

In the logistic regression analysis, only the presence of anemia (OR 2.82; 95% CI 1.11-7.14) and diarrhoea (OR 10.38; 95% CI 4.22-25.50) were risk factors for CD. The clinical and immune-histological characteristics of the celiac patients diagnosed in the study are shown in Table 2. No differences were observed in the frequency of classical presentation between patients diagnosed before or after 1999 (50% versus 58%, respectively). A gluten-free diet was strictly followed-up in 20 of the 22 adult celiac patients diagnosed.

| Gender | |

| Female | 18 (81.8%) |

| Male | 4 (18.2%) |

| Age (yr) | 50 (19-77) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Malabsorption syndrome | 12 (54.5%) |

| Anemia | 14 (63.6%) |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | 5 (22.7%) |

| Abnormal liver function test | 7 (31.8%) |

| Celiac relatives | 2 (9.1%) |

| Histology (Marsh type): | |

| I | 3 (13.6%) |

| II | 1 (4.5%) |

| III | 18 (81.8%) |

| Serology1 | |

| AGA | 13 (86.7%) |

| EMA | 17 (89.5%) |

| TTG | 8 (88.9%) |

| HLA-DQ22 | 18 (100%) |

| Autoimmune associated diseases3 | 2 (9.1%) |

| Mortality4 | 2 (9.1%) |

This study shows the changes observed over a period of 15 years (1990-2004) in the performance of duodenal biopsy in an endoscopy unit for adults in Spain. At present, the practice of duodenal biopsy during upper GI endoscopies is common. During the period 1990-1994 duodenal biopsy was made in 1.9% of the endoscopic explorations, while during the period 2000-2004 this was 12.8%.

Advancement in the knowledge of CD has led to an increase in the indications for performing duodenal biopsy. It is currently known that mild digestive symptoms (dyspepsia, abdominal discomfort, etc), or analytical alterations (anemia, iron deficiency or hypertransaminasaemia), could be some forms of presentation of CD[1]. We observed that during the first 5-year period, duodenal biopsy was usually made in persons with a classical or malabsorption syndrome, while in the later periods this was mainly performed in subjects with anemia (data not shown). Certain risk groups have been well characterised[19,20], which has meant that during the upper GI endoscopies practised for whatever reason in persons belonging to these risk groups, duodenal biopsy is made even in the absence of symptoms of enteropathy or without previous serological studies.

CD was diagnosed more frequently in females than in males (3% vs 1%), although gender was not a significant risk factor for CD, as has been observed in other similar studies[14]. Only anemia and diarrhoea were found to be risk factors for CD. The prevalence of CD found in patients with anemia (2.7%) is included in the wide range communicated in previous studies (1.8% to 13.7%)[6-11]; the differences are due mainly to the diverse selection criteria of patients with anemia, since if ferropenic refractory patients are included[6,7] or subjects in which other causes of anemia have been ruled out[7], the frequency of CD has been higher; on the other hand, the diagnostic strategy used also influences the results, as some studies have performed serological screening prior to duodenal biopsy[6,8], while in others a duodenal biopsy has been performed in all cases[7,11] or only in those in which another cause to justify the anemia was not found during the endoscopic exploration[10].

We wish to emphasize that our study is based on clinical practice over a long period of time, for which reason various factors could have influenced the results. Thus, the percentage of patients with anemia in whom duodenal biopsy was performed has increased over the periods of time analysed as a consequence of a greater knowledge of the manifestations of the disease; although in the management guides of ferropenic anemia duodenal biopsy is recommended during the endoscopic procedure indicated in order to rule out causes of such in the upper GI tract[4], this was only undertaken at the end of the period analysed in a percentage of 73% of the cases; the degree of fulfilment of this recommendation in countries such as the USA or the UK is low (10% and 46%, respectively)[21,22], in spite of the fact that it has been shown that duodenal biopsy for CD in a patient with anemia is a cost-effective approach[23]. We also observed that there were differences in the degree of implication of the endoscopist in the diagnosis of the disease (data not shown); in this sense, differences in the performance of duodenal biopsy among digestive endoscopic services, in the same country, have been reported[21].

The generalization of serological testing in the later periods of the study, above all in the primary care level, allowed the selection for duodenal biopsy of celiac patients with anemia as the only manifestation of the disease; on the other hand, 13 out of 14 celiacs with anemia presented specific antibodies for CD (the only negative case had a mild intestinal lesion - Marsh type 1). These data support the strategies of serological screening in subjects with anemia at primary care level[24,25], in blood donors[26] or in biochemistry laboratories[27] as an effective method of increasing the number of patients diagnosed with silent CD.

We found that adults diagnosed with CD had a mainly classical clinical presentation (55% with diarrhoea) and ferropenic anemia (64%), for which reason we believe that there must still be a large part of the celiac iceberg (silent or atypical forms) remaining undiagnosed. The prevalence of CD in the adult general population in our area, has been estimated to be 1/389[15], which means that only one in nine celiacs could be diagnosed, this being similar to that reported for other geographical areas[1].

We conclude that duodenal biopsy performed during routine upper GI endoscopy, has been incorporated into the daily clinical practice in digestive endoscopic services. This has permitted a significant increase in the number of patients diagnosed with CD, although these are probably only a small percentage of the true number of celiacs in the general population. In our area, the existence of anemia and diarrhoea are the most common risk factors associated with the presence of CD. Clinicians should consider CD as a possible cause of unexplained anemia, and gastroenterologists should biopsy the duodenum when exploring patients with iron-deficiency anemia and/or chronic diarrhoea, even if biopsies are not specifically required.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:636-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 804] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, Hoffenberg EJ, Horvath K, Murray JA, Pivor M. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 752] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Collin P, Reunala T, Rasmussen M, Kyrönpalo S, Pehkonen E, Laippala P, Mäki M. High incidence and prevalence of adult coeliac disease. Augmented diagnostic approach. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1129-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goddard AF, McIntyre AS, Scott BB. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2000;46 Suppl 3-4:IV1-IV5. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Thomas PD, Forbes A, Green J, Howdle P, Long R, Playford R, Sheridan M, Stevens R, Valori R, Walters J. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, 2nd edition. Gut. 2003;52 Suppl 5:v1-v15. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Corazza GR, Valentini RA, Andreani ML, D'Anchino M, Leva MT, Ginaldi L, De Feudis L, Quaglino D, Gasbarrini G. Subclinical coeliac disease is a frequent cause of iron-deficiency anaemia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Annibale B, Severi C, Chistolini A, Antonelli G, Lahner E, Marcheggiano A, Iannoni C, Monarca B, Delle Fave G. Efficacy of gluten-free diet alone on recovery from iron deficiency anemia in adult celiac patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Ransford RA, Hayes M, Palmer M, Hall MJ. A controlled, prospective screening study of celiac disease presenting as iron deficiency anemia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Karnam US, Felder LR, Raskin JB. Prevalence of occult celiac disease in patients with iron-deficiency anemia: a prospective study. South Med J. 2004;97:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mandal AK, Mehdi I, Munshi SK, Lo TC. Value of routine duodenal biopsy in diagnosing coeliac disease in patients with iron deficiency anaemia. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:475-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Grisolano SW, Oxentenko AS, Murray JA, Burgart LJ, Dierkhising RA, Alexander JA. The usefulness of routine small bowel biopsies in evaluation of iron deficiency anemia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wahnschaffe U, Ullrich R, Riecken EO, Schulzke JD. Celiac disease-like abnormalities in a subgroup of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1329-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shahbazkhani B, Mohamadnejad M, Malekzadeh R, Akbari MR, Esfahani MM, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Sotoudeh M, Elahyfar A. Coeliac disease is the most common cause of chronic diarrhoea in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Collin P, Rasmussen M, Kyrönpalo S, Laippala P, Kaukinen K. The hunt for coeliac disease in primary care. QJM. 2002;95:75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Riestra S, Fernández E, Rodrigo L, Garcia S, Ocio G. Prevalence of Coeliac disease in the general population of northern Spain. Strategies of serologic screening. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cilleruelo Pascual ML, Román Riechmann E, Jiménez Jiménez J, Rivero Martín MJ, Barrio Torres J, Castaño Pascual A, Campelo Moreno O, Fernández Rincón A. [Silent celiac disease: exploring the iceberg in the school-aged population]. An Esp Pediatr. 2002;57:321-326. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Castaño L, Blarduni E, Ortiz L, Núñez J, Bilbao JR, Rica I, Martul P, Vitoria JC. Prospective population screening for celiac disease: high prevalence in the first 3 years of life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1142] [Cited by in RCA: 1205] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vitoria JC, Castaño L, Rica I, Bilbao JR, Arrieta A, García-Masdevall MD. Association of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and celiac disease: a study based on serologic markers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Farré C, Humbert P, Vilar P, Varea V, Aldeguer X, Carnicer J, Carballo M, Gassull MA. Serological markers and HLA-DQ2 haplotype among first-degree relatives of celiac patients. Catalonian Coeliac Disease Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2344-2349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Harewood GC, Holub JL, Lieberman DA. Variation in small bowel biopsy performance among diverse endoscopy settings: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1790-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Patterson RN, Johnston SD. Iron deficiency anaemia: are the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines being adhered to. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:226-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Harewood GC. Economic comparison of current endoscopic practices: Barrett's surveillance vs. ulcerative colitis surveillance vs. biopsy for sprue vs. biopsy for microscopic colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1808-1814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hin H, Bird G, Fisher P, Mahy N, Jewell D. Coeliac disease in primary care: case finding study. BMJ. 1999;318:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, Ward AM, McCloskey EV, Hadjivassiliou M, Lobo AJ. A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Unsworth DJ, Lock RJ, Harvey RF. Improving the diagnosis of coeliac disease in anaemic women. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:898-901. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Howard MR, Turnbull AJ, Morley P, Hollier P, Webb R, Clarke A. A prospective study of the prevalence of undiagnosed coeliac disease in laboratory defined iron and folate deficiency. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:754-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |