Published online Aug 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5017

Revised: October 20, 2005

Accepted: October 26, 2005

Published online: August 21, 2006

AIM: To evaluate the gastric permeability after both acute and chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and to assess the clinical usefulness of sucrose test in detecting and following NSAIDs- induced gastric damage mainly in asymptomatic patients and the efficacy of a single pantoprazole dose in chronic users.

METHODS: Seventy-one consecutive patients on chronic therapy with NSAIDs were enrolled in the study and divided into groups A and B (group A receiving 40 mg pantoprazole daily, group B only receiving NSAIDs). Sucrose test was performed at baseline and after 2, 4 and 12 wk, respectively. The symptoms in the upper gastrointestinal tract were recorded.

RESULTS: The patients treated with pantoprazole had sucrose excretion under the limit during the entire follow-up period. The patients without gastroprotection had sucrose excretion above the limit after 2 wk, with an increasing trend in the following weeks (P = 0.000). A number of patients in this group revealed a significantly altered gastric permeability although they were asymptomatic during the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Sucrose test can be proposed as a valid tool for the clinical evaluation of NSAIDs- induced gastric damage in both acute and chronic therapy. This tecnique helps to identify patients with clinically silent gastric damages. Pantoprazole (40 mg daily) is effective and well tolerated in chronic NSAID users.

- Citation: Maino M, Mantovani N, Merli R, Cavestro GM, Leandro G, Cavallaro LG, Corrente V, Iori V, Pilotto A, Franzè A, Mario FD. Effects of chronic therapy with non-steroideal antinflammatory drugs on gastric permeability of sucrose: A study on 71 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(31): 5017-5020

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i31/5017.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5017

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are largely consumed among the general populations worldwide, representing one of the most prescribed drugs[1-6]. The main factor limiting their use is a high rate of adverse events, especially gastrointestinal toxicity[7]. Although only a small number of patients develop serious gastrointestinal complications, they represent a large number of patients due to the widespread use of NSAIDs[7-9].

Gastrointestinal toxicity is often clinically silent even in high risk groups due to the intrinsic analgesic activity of NSAIDs[10]. Therefore aspecific symptoms such as dyspepsia, heartburn, nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain are frequently ignored by patients suffering, for example, from a chronic pain due to the underlying ostheoarticular diseases.

A recent meta-analysis indicates that the association between use of NSAIDs and dyspepsia is unclear because of the variability of the terminology used in literature to report GI symptoms[11]. Taking the “strict” definition of dyspepsia into account, based solely on epigastric pain-related symptoms, NSAIDs increase the risk of dyspepsia of 36%, which is useful for creating standard definitions. Endoscopy for diagnosis of NSAIDs- induced upper gastrointestinal damage is precise, sensitive and easy to perform, but it cannot be proposed as a screening test, especially in asymptomatic patients. Gastrointestinal permeability is usually tested to assess the small bowel function in many diseases such as coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease[12,13]. Sucrose test is a simple, economic and non-invasive test for the assessment of gastric permeability and correlates with alterations detected with histology as previously demonstrated[14]. Some authors have proposed sucrose test as an index for monitoring hypertensive gastropathy, confirming its clinical usefulness. Which is the best strategy in preventing NSAIDs-related adverse events in the gastrointestinal tract is still controversial[16].

Many clinical trials have analyzed the efficacy and safety of concurrent administration of NSAIDs and misoprostol, H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in reducing the occurrence of serious gastrointestinal events.

Available data show that PPIs are well tolerated and effective in preventing and treating non steroideal antinflammatory drug-related mucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract[17-20].

The aim of this study was to establish the clinical usefulness of sucrose test in early identification of both acute and chronic gastric mucosal damage irrespective of the presence of any symptoms and to define the efficacy of a single daily PPI administration in protecting gastric mucosa in patients requiring long term treatment with NSAIDs.

Seventy-one consecutive outpatients (38 females, 33 males, mean age 53 years, range 26-78 years) with chronic use of NSAIDs (ASA, diclofenac, celecoxib) for rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, ostheoarthritis) were enrolled in the study. None of them consumed gastroprotective agents (PPIs, H2 -blockers, misoprostol).

All patients were asymptomatic at baseline and had no previous history of peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal surgery or malignancies.

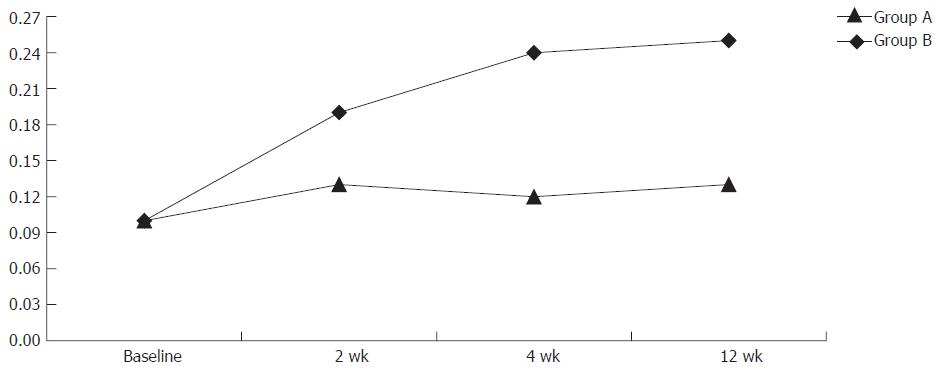

Sucrose permeability test (40 mg of sucrose in 100 mL of water) was performed at baseline. The patients were divided in group A (31 patients receiving 40 mg pantoprazole daily) and group B (40 patients not receiving PPI therapy). Sucrose test was repeated 2, 4, and 12 wk after follow-up (Figure 1).

The patients gave their informed consent according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Symptoms were recorded according to the presence of mild dyspepsia as previously defined (score 0 = absence; score 1 = mild dyspepsia)[11].

To evaluate gastric permeability, the subjects were requested to ingest 40 g sucrose in 100 mL of water after fasted for 8 h. Urine samples were collected in the following 6 h into a container with the addition of 2 mL of 20% chlorohexidine to prevent bacterial degradation. No food or liquid intake (except a glass of water) was allowed during urine collection. Urine samples were refrigerated and taken to the laboratory within 24 h. An aliquot was stored at -20°C for subsequent analysis.

Sucrose assay was based on its hydrolysation by β-fructosidase to glucose and fructose. Glucose was measured by the hexokinase method. The concentration of the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) was measured at 340 nm. Results were expressed as the percentage of excretion of the ingested dose of sucrose and the normal range was < 0.15% sucrose.

Data were reported as mean ± SD. Values of sucrose test at baseline and after 2 and 4 wk in group B were evaluated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Comparison between sucrose test values in groups A and B was made with Mann-Whitney test. Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois 60606) was used for calculations. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

At baseline all the patients showed a mean sucrose value of 0.10% ± 0.08%. Two weeks later, all the patients underwent an additional sucrose test which showed a mean value of 0.13% ± 0.08% in group A and 0.19% ± 0.06% in group B. At wk 4 sucrose test showed 0.12% ± 0.0 7% in the pantoprazole group and 0.24% ± 0.07% in the other group (P = 0.000). Sucrose test was then repeated after 12 wk, showing the mean values of 0.13% ± 0.10% in group A and 0.25% ± 0.07% in group B respectively (P = 0.000) (Figure 1). At wk 4 the mean value of sucrose test decreased in 7 patients of group A and in 15 patients of group B. At wk 12 the mean value of sucrose test decreased in 3 an additional 3 patients of group A and none of group B. Forty-six patients (21 in group A and 25 in group B) completed the follow-up (wk 12).

Regarding the consumption of NSAIDs, the patients on ASA therapy and without gastroprotection showed the mean sucrose values of 0.10% ± 0.05% at baseline and 0.17% ± 0.06%, 0.24% ± 0.07%, 0.28% ± 0.06% at 2, 4 and 12 wk respectively.

In the patients consuming diclofenac and without gastroprotection, the mean sucrose values were 0.08% ± 0.03% at baseline and 0.24% ± 0.05%, 0.31% ± 0.06% and 0.30 ± 0.04% at 2, 4 and 12 wk respectively.

In the patients consuming celecoxib, the mean sucrose values were 0.08% ± 0.04% at baseline and 0.04% ± 0.05%, 0.17% ± 0.04% and 0.15% ± 0.06% at 2, 4 and 12 wk respectively. The patients with no symptoms accounted for 47.4%, 31.6% and 32.6% after 2, 4 and 12 wk respectively.

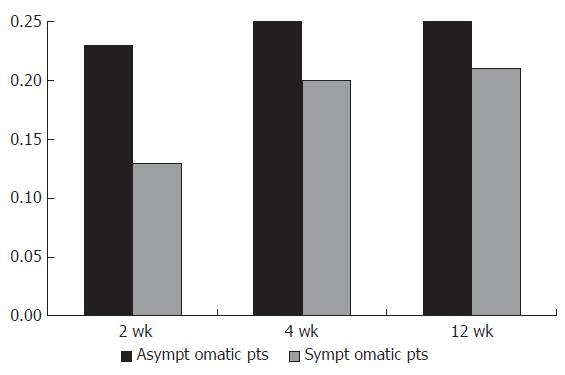

In group B, 37.5%, 32% and 28% of the patients remained asymptomatic after 2, 4 and 12 wk respectively. However, their mean sucrose values were 0.13% ± 0.08%, 0.20% ± 0.06% and 0.21% ± 0.05% during the follow-up period.

The mean sucrose values in patients complaining of mild dyspepsia in group B were 0.23% ± 0.04%, 0.25% ± 0.08% and 0.25% ± 0.07% after 2, 4 and 12 wk (Figure 2).

Sucrose test is considered as a useful tool for predicting the presence of clinically significant gastric disease after repetitive exposure to NSAIDs. Furthermore, sucrose test has been shown to be able to detect the differencies in both formulation and dose of NSAIDs[13].

NSAIDs reduce secretion of both bicarbonate and mucus, which are two of the most important gastric mucosal defensive mechanisms. In fact, bicarbonates stimulate cell renewal and repair, while mucus that coats over the mucosal lining provides a substrate for rapid restitution processes[21,22]. NSAIDs-induced damage allows permeation of macromolecules such as sucrose through the gastric mucosa.

We have previously proposed sucrose test together with serum pepsinogens as useful non-invasive methods to assess histological damages as they show a good relationship with histological findings[14].

In our study, the patients without PPI therapy showed increasing mean values of sucrose test during the acute period (0.19% after 2 wk and 0.24% after 4 wk) compared to the 0.10% at baseline with a statistically significant difference (P = 0.000), suggesting that sucrose test is able to detect gastric mucosal damages in acute ingestion of NSAIDs.

The subjects on chronic therapy showed a stable mean value of 0.25% after 12 wk, without any statistically significant difference (P = 0.39). This can be explained with the underlying mechanisms of NSAIDs-induced gastric damage involving both direct irritant action and systemic effect due to the inhibition of cyclooxigenase (COX) activity, which represents their main pharmacological effect. However, some authors suggest that COX-independent effects may be important in inducing mucosal cell apoptosis and microvascular perturbation with subsequent acute lesions[23].

Several studies have indicated that acute damage is much more widespread than damage observed after several days or weeks, indicating that the gastric mucosa has adaptive mechanisms that compensate for NSAIDs-induced injury[24]. Although the mechanisms involved in adaptation have not been defined yet, they reflect the capacity of a rapid epithelial repair, which in turn epends on restitution and cell replication[25].

In our study, the symptomatic patients showed a urinary sucrose excretion above the normal limit, suggesting a gastric damage. However, an alteration in gastric permeability was also undetectable by endoscopy, suggesting that sucrose test represents the only available method to detect “mild to moderate” gastric damages.

In our study, a proportion of patients without gastroprotection revealed higher mean sucrose excretion than normal although they remained completely asymptomatic. These patients had a normal sucrose test at baseline and after 4 wk, but the excretion increased significantly in the following weeks, suggesting that they had mucosal damage. These results indicate an important clinical role of sucrose test which can be used to identify gastric mucosal damages irrespective of the presence of a clinical picture, which is often absent in NSAIDs-induced damage.

Sucrose test could be performed sequentially in high risk patients such as chronic users and rheumatic patients, and could identify early gastric mucosal damages.

The best strategy in preventing NSAIDs-induced damage is still controversial[13-19]. First, gastrointestinal complications may be avoided by the use of NSAID analgesics when possible. Second, using NSAIDs at their lowest effective dose decreases the risk of complications. Third, medical cotherapy could be used in patients with increased risk of complications. Finally, less injurious NSAIDs such as COX-2-specific inhibitors should developed to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal events.

Many studies have demonstrated that PPIs give a good protection against both duodenal and gastric ulcers in patients taking NSAIDs[27,28]. In addition, these drugs are safe and better tolerated as co-therapies than H2-antagonists or prostaglandin.

Some studies have demonstrated a significant benefit of pantoprazole in preventing NSAIDs-induced peptic ulcers. There are also data regarding the efficacy of pantoprazole in preventing gastric lesions in rheumatic patients receiving long term treatment with NSAIDs. It has been reported that pantoprazole (40 mg daily) is well tolerated and more effective than placebo in preventing peptic ulcer in patients with rheumatic diseases on prolonged therapy with NSAIDs[28-30].

In our study, the patients on pantoprazole therapy showed lower mean values of sucrose test both in acute and chronic treatment compared with those without gastroprotection, confirming the efficacy of this drug in protecting gastric mucosa. The presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms was lower in patients receiving pantoprazole during the period of observation.

In conclusion, sucrose test can be used in the follow-up of patients on chronic therapy with NSAIDs. In fact, this method is non-invasive, well tolerated and inexpensive, and can be easily performed sequentially in chronic users of NSAIDs. This approach helps identify high risk patients that should undergo an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy if economic consideration is taken into account.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Retail & Provider Perspective, National Prescription Audit, 1999-2000. Plymouth, PA: IMS Health 2000; . |

| 2. | Editoriale: Il mercato farmaceutico mondiale nel 2001. Bollettino Informazione sui farmaci. 2001;6:275-277. |

| 3. | Koutsos MI, Shiff SJ, Rigas B. Can nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs be recommended to prevent colon cancer in high risk elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 1995;6:421-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, Budinger S, Paskett E, Keresztes R, Petrelli N, Pipas JM, Karp DD, Loprinzi CL. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:883-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 856] [Cited by in RCA: 816] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen D, Bresalier R, McKeown-Eyssen G, Summers RW, Rothstein R, Burke CA. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:891-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1021] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rogers J, Kirby LC, Hempelman SR, Berry DL, McGeer PL, Kaszniak AW, Zalinski J, Cofield M, Mansukhani L, Willson P. Clinical trial of indomethacin in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1609-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:521-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Laine L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:489-504. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888-1899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1316] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Pounder R. Silent peptic ulceration: deadly silence or golden silence. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:626-631. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Straus WL, Ofman JJ, MacLean C, Morton S, Berger ML, Roth EA, Shekelle P. Do NSAIDs cause dyspepsia A meta-analysis evaluating alternative dyspepsia definitions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1951-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meddings JB, Sutherland LR, Byles NI, Wallace JL. Sucrose: a novel permeability marker for gastroduodenal disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1619-1626. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Davies NM. Review article: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal permeability. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:303-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Altavilla N, Moussa AM, Seghini P. Sucrose test and serum pepsinogens as markers of inflammation and damage in Helicobacter pylori related gastritis. Gut. 2002;51:A1-A120. |

| 15. | Laine L, Bombardier C, Hawkey CJ, Davis B, Shapiro D, Brett C, Reicin A. Stratifying the risk of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal clinical events: results of a double-blind outcomes study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1006-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Laine L. Approaches to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the high-risk patient. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:594-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, Geis GS. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:241-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 752] [Cited by in RCA: 688] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, Makuch R, Eisen G, Agrawal NM, Stenson WF. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 2000;284:1247-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2166] [Cited by in RCA: 2065] [Article Influence: 82.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, Day R, Ferraz MB, Hawkey CJ, Hochberg MC. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520-1528, 2 p following 1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2752] [Cited by in RCA: 2534] [Article Influence: 101.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lichtenberger LM. The hydrophobic barrier properties of gastrointestinal mucus. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:565-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Slomiany BL, Sarosiek J, Slomiany A. Gastric mucus and the mucosal barrier. Dig Dis. 1987;5:125-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pilotto A, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Franceschi M, Bozzola L, Valerio G. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection on upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly: a case-control study. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:586-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Morelli A. Mechanism of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-gastropathy. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33 Suppl 2:S35-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Graham DY, Smith JL, Spjut HJ, Torres E. Gastric adaptation. Studies in humans during continuous aspirin administration. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:327-333. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Schmassmann A. Mechanisms of ulcer healing and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1998;104:43S-51S; discussion 79S-80S. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Micklewright R, Lane S, Linley W, McQuade C, Thompson F, Maskrey N. Review article: NSAIDs, gastroprotection and cyclo-oxygenase-II-selective inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:321-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepañski L, Walker DG, Barkun A, Swannell AJ, Yeomans ND. Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:727-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bianchi Porro G, Lazzaroni M, Imbesi V, Montrone F, Santagada T. Efficacy of pantoprazole in the prevention of peptic ulcers, induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |