INTRODUCTION

Villous adenomas are benign epithelial lesions with malignant potential, which are usually encountered in the colon, less commonly in the small bowel or the ampulla of Vater, and extremely uncommonly in the bile ducts[1]. Since Saxe et al first reported a case of villous adenoma of the common bile duct (CBD) in 1988, a total of 17 cases have been reported so far in the literature[1-17].

We present what is to our knowledge, the first case of a mucin-secreting CBD adenoma presenting as acute pancreatitis due to mucus hypersecretion and showing the endoscopic finding of “fish-mouth” in the papilla of Vater.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the department of Internal Medicine complaining for upper abdominal pain radiating to the back, nausea and vomiting during the last six hours.

Physical examination demonstrated a well nourished man who appeared jaundiced. The abdomen was soft but revealed tenderness in the epigastrium and a movable, firm, non-tender mass in the right upper quadrant, which was felt to be a distended gallbladder. Previous medical history included a 3-mo period of dyspepsia. The patient did not mention previous episodes of fever or weight loss. He had never been abroad, was not on any drug or alcohol abuse and had no history of serious illness.

Laboratory investigations showed a total serum bilirubin level of 51 μmol/L (normal range 0-3 μmol/L), direct bilirubin level of 39 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase level of 548 U/L (normal range < 120 U/L), alanine transaminase level of 143 U/L (normal range < 45 U/L) and serum amylase level of 1720 U/L (normal range < 30 U/L). The hemogram revealed hemoglobin and hematocrit of 142 g/L and 44.6%, respectively, while white blood cell count was 16 100 /mm3. On abdominal ultrasound and CT the pancreas was edematous, the gallbladder was distended without calculi and the CBD was found to be dilated (12.5 mm), with a nonshadowing tissue mass in its distal end. The patient was treated conservatively with resolution of symptoms.

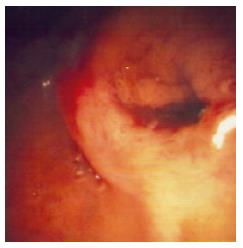

On seventh day, an endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopancreatography (ERCP) was performed and demonstrated a patulous papillary orifice of the major papilla (fish-mouth sign) with mucus exuding from it (Figure 1), a normal pancreatogram and a 2 cm × 1 cm intraluminal filling defect in the distal CBD (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Endoscopic view showing a dilated papillary orifice exiting mucus.

Figure 2 ERCP demonstrating an intraluminal filling defect in the distal common bile duct.

A 8.5Fr stent has been placed.

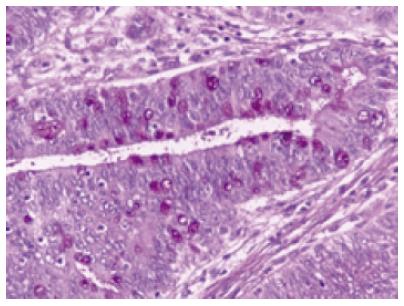

A sphincterotomy was performed and in order to rule out the presence of stone, a balloon was inserted, but nothing was retrieved. A subsequent lithotriptor-basket extraction took a fragment tissue out and a 8.5-French Cotton-Leung type plastic stent of 7 cm was placed. Because the histological examination of the retrieved tissue showed that the main mass was a villous adenoma, the mass was thought to be resectable with safety margins. The patient subsequently underwent a modified Whipple procedure. The histopathological examination of the specimen demonstrated that the tumor consisted of finger-like villous or papillary processes containing central thin cords of lamina propria lined by a neoplastic epithelium. The epithelial cells were tall columnar, pseudostratified with elongated or round atypical nuclei. Some of the cells contained large amounts of mucin within the apical cytoplasm. Focally goblet cells lied within the epithelium (Figure 3). No signs of hyperplasia or adenoma of the pancreas were observed in the specimen.

Figure 3 Surgical specimen showing that the tumor consists of tall, columnar, pseudostratified epithelial cells with elongated or round atypical nuclei.

Some of the cells contain large amounts of mucin within the apical cytoplasm (PAS X 400).

The patient recovered uneventfully and remains in good general condition, six months after discharge.

DISCUSSION

Adenomas of the bile ducts are divided into papillary adenomas, penduculated adenomas and sessile adenomas, according to the gross configuration of the tumors[18]. This classification replaced an earlier classification of papillomas and adenomas. Villous adenomas are thus classified as frond-like sessile adenomas[3]. Histologically, however, adenomas are classified into tubular, tubulovillous and villous adenomas.

The most common site for villous adenomas in the biliary tree is the CBD. These adenomas usually develop in the distal aspect of the CBD[18]; they are histologically similar to villous adenomas in the ampullary region, gallbladder and intestine and should probably be considered having similar biological behavior. The adenoma to carcinoma sequence is well accepted in the colon and most likely also applies in the ampullary region, gallbladder and bile ducts[19].

Of note, in reviewing the reported cases[1-17] of bile duct villous adenomas, the clinical picture includes painless jaundice, pruritus, upper abdominal pain, cholangitis and dyspepsia. The tumors rarely grow large enough to become palpable because of their site. The degree of jaundice has been described to fluctuate in some reports, which may be attributable to a ball valve effect of the tumor. Preoperative diagnosis or diagnosis without operation was possible in 6 out of 17 cases, mainly in recently reported cases, reflecting the current sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic techniques of the biliary tract and pancreas. Abdominal US and CT demonstrated dilation of the CBD and an intraductal tumor but were not capable of specifying any further the nature of the lesion. The absence of gallbladder calculi, as well as the absence of acoustic shadowing of the CBD mass in the patients, made the possibility of the lesion being calculus unlikely. In addition, in the absence of gallbladder sludge, sludge in the CBD is unusual. Moreover, differentiation of a villous adenoma from other nonshadowing solid lesions, such as blood clots, nonshadowing calculi, lipomas, fibromas, or carcinoid tumors on the basis of US and CT findings is difficult[5]. Echoendoscopy is a well proven technique with higher image resolution and greater diagnostic sensitivity than conventional imaging methods and would be useful to identify the nature of the lesion and exclude an invasive component.

It must be emphasized that two cases of coexisting biliary tract and intestinal polyps have been reported[20,21]. It has been proposed that bile duct adenomas are part of the spectrum of generalized gastrointestinal polyposis. Some authors[20-23] have suggested that upper gastrointestinal surveillance of patients with familiar adenomatous polyposis should routinely include imaging of the biliary tract.

Our case is both unique and challenging in that the CBD adenoma had close resemblance to intraductal papillary mucinous tumors (IPMT) of the pancreas. More specifically, it was composed of secreting cells, with hypersecretion of mucin. The hypersecreted viscous mucin led to obstruction of the papillary orifice, thus increasing the pancreatic intraductal pressure and activating the cascade of mechanism of pancreatitis. Moreover, the ”fish-mouth” sign in the major papilla is an endoscopic finding which has been discussed in mucin-secreting pancreatic tumors. As both lesions are encountered premalignant, complete resection of both of them is considered mandatory. Therefore, we suggest that the term IPMT of the bile ducts could be used to describe this rare condition.

In conclusion, our case reflects the need to consider a wide differential in patients presenting with acute pancreatitis and jaundice, especially in the absence of cholelithiasis and alcohol abuse.