Published online Aug 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4879

Revised: July 21, 2005

Accepted: August 11, 2005

Published online: August 14, 2006

AIM: To evaluate the prevalent topical therapeutic modalities available for the treatment of acute radiation proctitis compared to formalin.

METHODS: A total of 120 rats were used. Four groups (n = 30) were analyzed with one group for each of the following applied therapy modalities: control, mesalazine, formalin, betamethasone, and misoprostol. A single fraction of 17.5 Gy was delivered to each rat. The rats in control group rats were given saline, and the rats in the other three groups received appropriate enemas twice a day beginning on the first day after the irradiation until the day of euthanasia. On d 5, 10, and 15, ten rats from each group were euthanized and a pathologist who was unaware of treatment assignment examined the rectums using a scoring system.

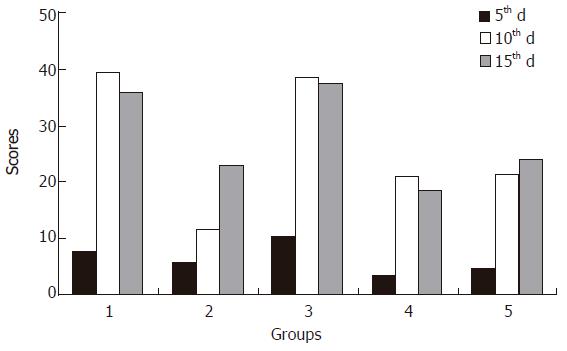

RESULTS: The histopathologic scores for surface epithelium, glands (crypts) and lamina propria stroma of the rectums reached their maximum level on d 10. The control and formalin groups had the highest and mesalazine had the lowest, respectively on d 10. On the 15th d, mesalazine, betamethasone, and misoprostol had the lowest scores of betamethasone.

CONCLUSION: Mesalazine, betamethasone, and misoprostol are the best topical agents for radiation proctitis and formalin has an inflammatory effect and should not be used.

- Citation: Korkut C, Asoglu O, Aksoy M, Kapran Y, Bilge H, Kiremit-Korkut N, Parlak M. Histopathological comparison of topical therapy modalities for acute radiation proctitis in an experimental rat model. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(30): 4879-4883

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i30/4879.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4879

Acute radiation proctitis is a major clinical complication of pelvic irradiation[1,2]. Rectum is exposed to high dose irradiation during radiotherapy of the rectal, cervical and prostate malignancies. The rate of complications, which decrease life quality, has been reported as high as 10%-15%[3,4].

The problem of radiation proctitis leads to prophylaxis studies. Sukralfat[5-9], anti-inflammatory agents[6,9], mesalazine[5] have been shown to be histopathological ineffective in clinical prophylaxis studies. In spite of the clinical comparative studies of these drugs there is no agreement on the therapy protocol[8,10-12].

There are several therapy modalities used for the protection and treatment of acute radiation proctitis and consequent chronic sequelae, including diet[13], sucralfate[14,15], antiinflamatuar agents like mesalazine[15,16], corticosteroids[5,10], formalin[17,18] and misoprostol[3,6]. However these medical approaches are not sufficiently effective and have only a limited benefit. The search for a more effective therapy should be continued.

The pathological features of irradiation begin in hours. Morphologic changes include loss of columnar shape, and nuclear polarity of enterocytes, epithelial degeneration, ulceration, nuclear pyknosis and karyorrhexis, crypt disintegration, mucosal edema, absent mitosis, crypt abscesses with prominent eosinophilic infiltrates[19].

The aim of this study was to compare the most prevalent topical therapeutic modalities used for acute radiation proctitis in a standard rat radiation proctitis model[20].

Female Sprague Dawley rats weighing 230-285 g at the age of 6 wk were obtained from the Institute for Experimental Medicine, Istanbul University. All animals were acclimatized for 7 d prior to experimentation in the laboratory of the mentioned institute, which was maintained at 22 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 55 ± 10% in a constant 12 h dark/light circle. The rats were housed in standard wire cages and fed with standard rodent chow and UV sterilized tap water. The approval of the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty was obtained and the experimental procedures in this study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki for the care and use of laboratory animals.

After irradiation each animal was weighed and examined every 2 d until the end of the experiment. Five groups (30 rats in each group) were used. Groups were defined as follows. Rats in control group were anesthetized, restrained and taped by the tail and legs on an acryl plate, irradiated and given saline enemas. Rats in mesalazine group were irradiated, and given mesalazine enemas (Salofalk, Ali Raif, Istanbul, Turkey)[21]. Rats in formalin group were irradiated, and given formalin enemas (4%)[22]. Rats in betamethasone group were irradiated, and given betamethasone enemas (Betnesol,Glaxo-Wellcome, Hamburg, Germany)[13]. Rats in isoprostol group were irradiated, and given misoprostol enemas (5 μg/kg)[23]. The enemas, which were prepared in 1 mL volume at body temperature, were given twice a day beginning on the first day after irradiation until the euthanasia day. The enemas were applied with a soft feeding tube and then the anus was temporarily closed with digital compress for five minutes.

Each rat was anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital intraperitoneally (40 mg/kg). Then 3 to 4 rats at a time were restrained and taped by the tail and legs on an acryl plate at a supine position. Lead shielding (5 half value layer) was used to cover the rat except for a 3 cm × 4 cm area of lower pelvis containing 2 cm length of rectum in the middle of the field. Irradiation was delivered with a cobalt -60 apparatus, the γ energy was 1.25 MeV, and a distance of 80 cm from the source to the surface was used. Dose rate of the irradiation was 121.49 Gy per min and 17.5 Gy in a single fraction was delivered to each rat. Ten rats from each group were selected randomly for gross and macroscopic examination and euthanized on d 5, 10, and 15. Two 5 mm segments of the rectum which was 1 cm proximal to anus were excised, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution and processed by routine techniques. Each specimen was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined under a light microscope by a pathologist who was unaware of treatment assignment.

The rectums were evaluated microscopically using a slightly modified scoring system reported by Hovdenak et al[7] by a pathologist who was blinded to the groups and the euthanasia days of specimens. A total of 13 characteristics of three mucosal structures (surface epithelium, glands, and lamina propria stroma) were used. The abnormalities of the 13 parameters were assessed as normal (score = 0) or abnormal, and ranked according to severity and arranged in quartiles: 1 = mildly abnormal; 2 = moderately abnormal; 3 = markedly abnormal: 4 = severely abnormal.

Results were presented as mean ± SD. Relationship between the groups was assessed using analysis of variance. Tukey or Tamhane’s test was chosen to test for equality of variances. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

There was no death during the study. For determination of the acute radiation injury and the response to the local therapy, 10 rats from each group were euthanized on d 5, 10 and 15 after the irradiation. The rats were apparently healthy until the day of sacrifice excluding three rats (2 in control group and 1 in formalin group), which “looked” ill and showed symptoms of diarrhea on the 10th d. The rectums of the rats were removed and examined grossly and histopathologically. Tissues from five specimens (including the three mentioned above) had severe damage and were inappropriate to be scored. They were thus excluded from the study.

The five samples excluded were two from control group on the 10th d due to the ischemic necrosis of the rectal mucosa, one from formalin group on the 10th d due to massive mucosal infarct, one from formalin group on the 15th d due to lymphocytic colitis, one from isoprostol group on the 15th d due to lymphoid hyperplasia and submucosal edema (Table 1).

| Structure | Characteristic |

| Surface epithelium | Loss of cellular height/flattening of cells |

| Cellular inflammatory infiltrate | |

| Glands (crypts) | Luminal migration of epithelial nuclei |

| Loss of goblet cells | |

| Mitotic activity | |

| Cryptitis (migration of segmental neutrophils | |

| through the crypt wall) | |

| Eosinophilic crypt abscesses | |

| Loss of glands | |

| Atrophy of glands | |

| Distortion of glands | |

| Lamina propria | Inflammation |

| Edema | |

| Congestion of blood vessels |

The mean histopathologic scores of the specimens are shown in Table 2.

On the 5th d the formalin group had the highest scores, followed by the control group. Mesalazine, betamethasone and misoprostol groups had the lowest scores. Table 2 gives the statistical comparison of the scores. There was no difference between control and formalin groups. The mesalazine, betamethasone and misoprostol groups had no difference between each other either. The control group had significantly higher scores than betamethasone group (P = 0.039). The formalin group had higher scores than the mesalazine, betamethasone and misoprostol groups (P = 0.028, 0.0001 and 0.003, respectively).

On the 10th d the control and formalin groups had the highest scores, followed by misoprostol, betamethasone and mesalazine groups (Table 2). The scores of the control and formalin groups were higher than those in the misoprostol, betamethasone and mesalazine groups (P = 0.0001). There was no difference between control and formalin groups. The mesalazine group had the significantly lowest scores (P = 0.0001). There was no statistically significant difference between misoprostol and betamethasone groups.

On the 15th d, the scores of formalin and control groups were the highest (Table 2). Misoprostol, mesalazine and betamethasone groups had lower scores. The formalin and control groups had significantly higher scores than the other groups (P = 0.0001). There was no difference between mesalazine and misoprostol groups. The betamethasone group had the lowest scores (P = 0.0001 for the control and formalin groups, and P = 0.044 for the misoprostol group).

The sum of the histopathologic scores on the euthanasia days are presented on Figure 1. The inflammatory processes of the control, formalin and betamethasone groups reached a maximum score on the 10th d and decreased on the 15th d. Since nflammation of the mesalazine and misoprostol groups increased on the 10th and 15th d, the scores of the last group were higher. The mean scores of all groups, except for the formalin group and the betamethasone group on the 10th and 15th d, were significantly different.

The aim of this study was to compare the histopathologic effects of formalin therapy with the most common agents used for radiation proctitis[4,12,18,24-26]. The consequential correlation between acute injury, which is common and usually self-limiting and chronic sequela has been demonstrated[27,28].

With a controlled radiation proctitis animal model, the four most widely used therapeutic approaches were studied in a blinded histopathologic comparison. This standard model has two handicaps: the impossibility to examine the same individual over the time and the relation of the pathologic scores to the clinical symptoms. To deal with these problems, we used groups of simultaneously sacrificed rats and a pathological scoring system obtained from a clinical study[7]. The chosen model was justified with comparison to the clinical series from the pathological point of view in regard to the duration after irradiation and the optimal dose for the human disease. The protective dose of various medications has been determined to be 17.5 Gy in single fraction[20,29].

The acute pathological findings on the rectal mucosa are reported to persist for two weeks[20,29]. An edema of the lamina propria was observed in a first couple of days, cryptitis and crypt abscesses were found on d 4 and 5, ulcers and regenerative processes could be determined on d 9 and 10, the mucosa was healed and then the chronic sequelae like fibrosis of the lamina propria arose on d 15[7].

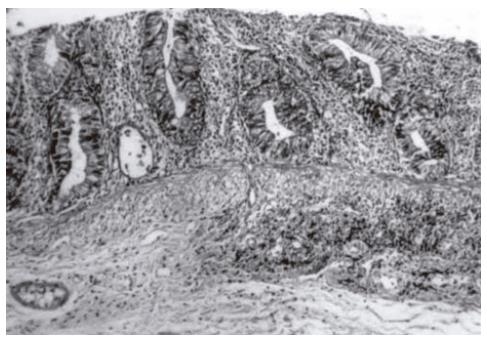

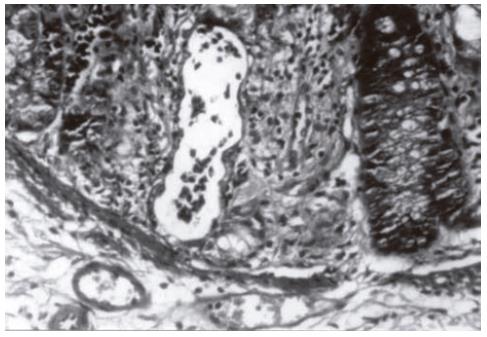

It was reported that the pathological differences in the 10th d groups are more obvious[7]. Cryptitis (Figure 2) and crypt abscesses (Figure 3) are the predominant characteristics of acute radiation toxicity. Two specimens of the control group showed mucosal iscemic necrosis. Two specimens of the formalin group showed mucosal infarct. One specimen of the misoprostol group showed crypt hyperplasia. The mean and sum mucosal and glandular pathologic scores of the formalin group were close to those of the control group. Betamethasone and misoprostol groups had statistically significant low scores.

The pathological process, determined with necrosis and edema of the mucosa and focal mucosal ulcers continued till the 15th d in euthanized animals of control and formalin groups. Betamethasone group showed the lowest pathologic scores on the 15th d.

The mucosal cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-8 have been reported to play a significant role in the etiology of radiation-induced proctoproctitis[30]. Mesalazine and betamethasone with cytokine suppressive effects have a curative outcome on this immunology-based disease, parallel to our results. The present study showed a solely descriptive basis of the histopathology, which determines the need and extent of the clinical therapy. The immunological contribution of the disease and the effect of therapeutic approaches need to be clarified.

It should be noted that two specimens were excluded from the study, one formalin roup specimen on the 15th d due to lymphocytic colitis, one misoprostol group specimen on the 15th d due to lymphoid hyperplasia and submucosal edema. Since lymphocytic colitis, lymphoid hyperplasia and submucosal edema were encountered over the whole rectal wall of the two specimens from the same animal, the scoring of them was thus impossible. Mistol has radiation protective and tissue regenerating effects, but its mechanism of action is not fully understood[8]. We showed that it could contribute to the healing process after irradiation.

Rectal formalin therapy has serious side effects like worsening of colitis, rectal pain, anal stenosis, rectal ulcers and anal incontinence[4]. These side effects have been reported even in series with good clinical results[5,14]. These effects are in accordance with our histopathologic findings.

In conclusion, formalin should not be used in order to avoid its toxic effects on mucosa. Mesalazine and betamethasone can be used for local therapy with no major superiority between each other. Controlled randomized prospective clinical trials are required to determine the best management of this disease.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Baughan CA, Canney PA, Buchanan RB, Pickering RM. A randomized trial to assess the efficacy of 5-aminosalicylic acid for the prevention of radiation enteritis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1993;5:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fajardo LF, Berthrong M. Radiation injury in surgical pathology. Part III. Salivary glands, pancreas and skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:279-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hellman S. Principles of Cancer Menagement: Radiation Therapy. Hellman SA. Rosenberg, (Eds): Cancer -Principles and Practice of Oncology. 5th ed. Com. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott-Raven Press 1997; 307-321. |

| 4. | Isenberg GA, Goldstein SD, Resnik AM. Formalin therapy for radiation proctitis. JAMA. 1994;272:1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Denton AS, Andreyev HJ, Forbes A, Maher EJ. Systematic review for non-surgical interventions for the management of late radiation proctitis. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:134-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Henriksson R, Franzén L, Littbrand B. Prevention and therapy of radiation-induced bowel discomfort. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1992;191:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hovdenak N, Fajardo LF, Hauer-Jensen M. Acute radiation proctitis: a sequential clinicopathologic study during pelvic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1111-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kneebone A, Mameghan H, Bolin T, Berry M, Turner S, Kearsley J, Graham P, Fisher R, Delaney G. The effect of oral sucralfate on the acute proctitis associated with prostate radiotherapy: a double-blind, randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:628-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zimmermann FB, Feldmann HJ. Radiation proctitis. Clinical and pathological manifestations, therapy and prophylaxis of acute and late injurious effects of radiation on the rectal mucosa. Strahlenther Onkol. 1998;174 Suppl 3:85-89. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Fischer L, Kimose HH, Spjeldnaes N, Wara P. Late progress of radiation-induced proctitis. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:801-805. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tjandra JJ, Sengupta S. Argon plasma coagulation is an effective treatment for refractory hemorrhagic radiation proctitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1759-1765; discussion 1771. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Luna-Pérez P, Rodríguez-Ramírez SE. Formalin instillation for refractory radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cavcić J, Turcić J, Martinac P, Jelincić Z, Zupancić B, Panijan-Pezerović R, Unusić J. Metronidazole in the treatment of chronic radiation proctitis: clinical trial. Croat Med J. 2000;41:314-318. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cunningham IG. The management of radiation proctitis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Das KM. Sulfasalazine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1989;18:1-20. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Freund U, Schölmerich J, Siems H, Kluge F, Schäfer HE, Wannenmacher M. Unwanted side-effects in using mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) during radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 1987;163:678-680. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gilinsky NH, Burns DG, Barbezat GO, Levin W, Myers HS, Marks IN. The natural history of radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis: an analysis of 88 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:40-53. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hanson WR, DeLaurentiis K. Comparison of in vivo murine intestinal radiation protection by E-prostaglandins. Prostaglandins. 1987;33 Suppl:93-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hong JJ, Park W, Ehrenpreis ED. Review article: current therapeutic options for radiation proctopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1253-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kan S, Chun M, Jin YM, Cho MS, Oh YT, Ahn BO, Oh TY. A rat model for radiation-induced proctitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:682-689. [PubMed] |

| 21. | van Bodegraven AA, Boer RO, Lourens J, Tuynman HA, Sindram JW. Distribution of mesalazine enemas in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gul YA, Prasannan S, Jabar FM, Shaker AR, Moissinac K. Pharmacotherapy for chronic hemorrhagic radiation proctitis. World J Surg. 2002;26:1499-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khan AM, Birk JW, Anderson JC, Georgsson M, Park TL, Smith CJ, Comer GM. A prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded pilot study of misoprostol rectal suppositories in the prevention of acute and chronic radiation proctitis symptoms in prostate cancer patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1961-1966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mathai V, Seow-Choen F. Endoluminal formalin therapy for haemorrhagic radiation proctitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ouwendijk R, Tetteroo GW, Bode W, de Graaf EJ. Local formalin instillation: an effective treatment for uncontrolled radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis. Dig Surg. 2002;19:52-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rubinstein E, Ibsen T, Rasmussen RB, Reimer E, Sørensen BL. Formalin treatment of radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:44-45. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Schultheiss TE, Lee WR, Hunt MA, Hanlon AL, Peter RS, Hanks GE. Late GI and GU complications in the treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang CJ, Leung SW, Chen HC, Sun LM, Fang FM, Huang EY, Hsiung CY, Changchien CC. The correlation of acute toxicity and late rectal injury in radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma: evidence suggestive of consequential late effect (CQLE). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Northway MG, Scobey MW, Geisinger KR. Radiation proctitis in the rat. Sequential changes and effects of anti-inflammatory agents. Cancer. 1988;62:1962-1969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Stein RB, Hanauer SB. Medical therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:297-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |