Published online Jul 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4561

Revised: July 22, 2005

Accepted: August 3, 2005

Published online: July 28, 2006

AIM: To demonstrate the necessity of intraoperative endoscopy in the diagnosis of secondary primary tumors of the upper digestive tract in patients with obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinoma.

METHODS: Thirty-one patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma had been operated, with radical intent, at our Institution in the period between 1978 and 2004. Due to obstructive tumor mass, in 7 (22.6%) patients, preoperative endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus and stomach could not be performed. In those patients, intraoperative endoscopy, made through an incision in the cervical esophagus, was standard diagnostic method for examination of the esophagus and stomach.

RESULTS: We found synchronous foregut carcinomas in 3 patients (9.7%). In two patients, synchronous carcinomas had been detected during preoperative endoscopic evaluation, and in one (with obstructive carcinoma) using intraoperative endoscopy. In this case, preoperative barium swallow and CT scan did not reveal the existence of second primary tumor within esophagus, despite the fact that small, but T2 carcinoma, was present.

CONCLUSION: It is reasonable to use intraoperative endoscopy as a selective screening test in patients with obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinoma.

- Citation: Pesko P, Bjelovic M, Sabljak P, Stojakov D, Keramatollah E, Velickovic D, Spica B, Nenadic B, Djuric-Stefanovic A, Saranovic D, Todorovic V. Intraoperative endoscopy in obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(28): 4561-4564

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i28/4561.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4561

The rate of synchronous primary cancers in the upper aerodigestive tract in the reported literature varies widely depending on the population surveyed and the thoroughness of the methods used to evaluate these patients[1]. In 25 studies published over 25 years, the average rate of synchronous primary upper aerodigestive cancers was 4%, ranging from 1.5% to 18%[2]. The relative risk of developing esophageal cancer in patients with head and neck cancer has been reported as being 3-20 times greater than that of control subjects from the general population[3-5]. The phenomenon of neoplastic multicentricity could affect the therapeutic approach, and cause local treatment failure.

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the necessity of intraoperative endoscopy in the diagnosis of secondary primary tumors in upper digestive tract in the patients with obstructive carcinoma of the hypopharynx.

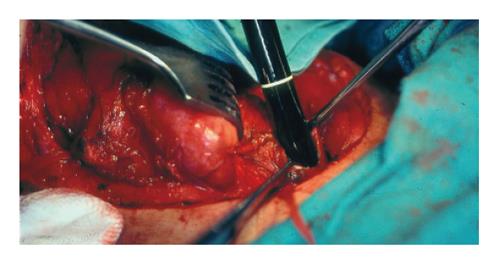

In the period between January 1st, 1978 and January 1st, 2004, 31 patients with hypopharyngeal squamocellular carcinoma had been operated at the Department of Esophagogastric Surgery, First University Surgical Hospital, Clinical Center of Serbia. In most patients a complete preoperative work-up was performed. Tumor resectability was assessed by means of chest X-ray, barium swallow, esophagoscopy (flexible and rigid), tracheobronchoscopy, ENT evaluation, thoracic and neck CT scan and ultrasonography. In patients with obstructive lesions, where preoperative esophagogastroscopic evalua-tion was not feasible, intraoperative endoscopy (with lugol staining method) through cervical esophagotomy was performed (Figure 1). Intraoperative endoscopy was performed in standard manner with diagnostic fiberoptic endoscope. Instrument was introduced in the esophagus through incision in the esophageal wall, made below lower border of the tumor. When tumor involved cervical esophagus and extended to the thoracic inlet, procedure was not feasible.

For the diagnosis of multiple separate (synchronous) primary carcinomas we followed standard criteria[6]: (1) neoplasms must be clearly malignant as determined by histological evaluation; (2) each neoplasm must be geographically separate and distinct. The lesions should be separated by normal-appearing mucosa. If a second neoplasm is continuous to the initial primary tumor, or is separated by mucosa with intraepithelial neoplastic change, two lesions should be considered as confluent growth rather than multicentric carcinomas; (3) the possibility that the secondary neoplasm represents a metastasis should be excluded. The observation that the invasive carcinoma arises from an overlying epithelium, which demonstrates a transition from carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma is helpful, and when the separate foci have significant difference in histology, the diagnosis of separate primary cancer is appropriate.

Mean age of the patients in our study was 53.5 years (range 36-72 years). The male to female ratio was 1:2.1. The most common complaint was dysphagia (83.9%), indicating an advanced disease. We had no experience with stage I and II carcinoma. Stage III and IV accounted for 23 (74.2 %) and 8 (25.8%) respectively. Due to obstructive tumor mass, in 7 (22.6%) patients, preoperative contrast radiography was not conclusive, and preoperative endoscopic evaluation could not be performed. Obstructive tumors were predominantly localized in postcricoid region, and mostly infiltrating esophageal ostium. In those patients intraoperative endoscopy, made through incision on the cervical esophagus (below hypopharyngeal tumor), was standard diagnostic method for examination of the esophagus and stomach.

In our series, we found synchronous foregut carci-nomas in 3 patients (9.7%), two of them with synchronous carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus, and one with stomach carcinoma. In two patients, synchronous carcinomas had been detected during preoperative endoscopic evaluation, and in one patient (with obstructive carcinoma) using intraoperative endoscopy. In this patient, preoperative barium swallow and CT scan did not detect existence of second primary tumor within esophagus despite the fact that small, but T2 carcinoma, was present.

With regards to risk factors for head and neck, or esophageal carcinomas, genetic factors and enviromental factors, such as smoking and alcohol, have been reported to be important[7,8]. These data suggest the concept of "field carcinogenesis"[6]. According to Martins[9] and Kumagai[10] more than 70% of patients with synchronous hypopharyngeal carcinoma have second malignancy in the esophagus, but second gastric malignancy could not be detected. Kodama et al[11] also reported high prevalence of synchronous carcinomas of the pharynx and esophagus. Gluckman et al[12] recommended the use of panendoscopy in the evaluation of all head and neck cancers. Likewise, McGuirt[13], Leipzig[14], and Shapshay[15] also recommended panendoscopy due to frequent association of head and neck, esophageal and lung carcinomas.

One of the most difficult problems we confront clinically, in the preoperative examination, is the subgroup of patients where esophageal and gastric fiberscopy (GIF) could not be performed due to obstructive hypopharyn-geal mass. Without knowning the existence of multiple lesions, we cannot decide the proper therapeutic (surgical) plan. Martins et al[9] reported that esophagoscopy and esophagography was attempted in 97% of patients in their series, but these examinations failed to evaluate the entire esophagus in 46% patients because of severe obstruction. In addition, very few patients (5 out of 36) underwent lugol staining during esophagoscopy. Although all patients were appropriately studied preoperatively, in only two cases multiple tumors were diagnosed before surgery. The remaining multiple synchronous carcinomas were obviously missed. Second primary tumor was, as a rule, located distal to the main obstructing carcinoma, preventing adequate total esophageal examination. Akyiama[16] cited intraoperative esophagoscopy as an important step in such patients. However, this procedure is not possible when tumors widely infiltrate cervical esophagus. Intraoperative endoscopy made through incision below the tumor, could be performed in most patients with obstructive carcinoma of postcricoid region, even when tumors infiltrate the esophageal ostium.

To justify the selective use of intraoperative endoscopy as a diagnostic tool for patients with obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinoma, a number of issues need to be considered. The procedure should significantly improve the diagnosis of synchronous primary tumors when compared with non-invasive radiologic investigations, including barium swallow (BaSw) and chest computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Symptom directed studies are not feasible because patiens already have severe dysphagia due to obstructive proximal carcinoma. In addition, second primary tumor could be of early stage and does not cause subjective symptoms even in absence of proximal obstruction. Kohmura

et al[6] support the view that in patients with obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinomas MRI should be performed. According to this data, esophageal mass lesions or hypertrophic mucosa detected by MRI require esophageal blunt dissection, due to possibility of multiple primary malignancies. In addition, Kohmura et al[6] proposed that there is little chance of multiple malignancies in the esophagus if there are no abnormalities by MRI. They also pointed out that endoscopic evaluation is favorable whenever is feasible. However, many authors agree that the role of MRI in the examination of gastrointestinal tract, apart from the liver, is limited[17,18]. CT has shown similar limitations in the diagnosis and staging of esophagogastric tumors with accuracy rate of only 60% or less[19,20]. Many others[21-23] agree that endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has clearly showed superior accuracy for T and N staging of esophageal and gastric carcinoma as compared with CT, but has the same limitations as endoscopic examination in the patients with obstructive tumors. Miniprobe sonography showed favourable results in the diagnosis and staging of esophageal tumors[18], but unfortunately, in most institutions is not available in routine clinical practice.

The second issue to be addressed is whether the diagnosis of a second primary tumor would change the primary treatment approach for the individual patient. Panosetti et al[24] in large series of patients, demonstrated that the discovery of a synchronous second primary tumor altered the treatment approach in 50% of patients. Many reports favour free jejunal interposition as a reconstructive method rather than gastric transposition[25-27]. These approaches may leave behind a premalignant or malignant lesion in the esophagus. One of the strongest arguments for total pharyngolaryngoesophagectomy and gastric transposition is the presence, or possibility of synchronous or metachronous primary in the esophagus. But then, stomach should be completely evaluated by endoscopy and x-ray before surgery, due to possibility of presence of the malignant tumor within stomach. Since the stomach is commonly used for reconstruction of the digestive tract after esophagectomy, another substitute must be considered for patients with synchronous gastric cancer.

The third issue to consider is the prognosis of patients with synchronous primary tumors, and impact of detection on overall survival. Advances in therapeutic methods have significantly improved local control rates. Still, many patients are developing distant metastases. Panosetti et al[24] reviewed the impact of survival of patients with synchronous versus metachronous second primary tumors. In a large series, these authors demonstrated that patients who were initially seen with synchronous primary tumors had 5-year survival rates of 18% vs 55% for those with metachronous tumors. These suggest that the overall survival for patients with detectable synchronous primary is quite poor. Martins et al[9] showed that more than 80% of second synchronous primaries were invasive carcinomas. In contrary, Kumagai[10] and Kohmura[6] found that most of the esophageal carcinomas accompaning advanced hypopharyngeal carcinomas were of early stage and that surgical excision could positively influence the prognosis. Thus, with the possibility of multiple intraesophageal cancer, endoscopic screening of the esophagus with lugol dye method in patients with head and neck cancer is necessary before treatment[13,28,29]. In our series, single synchronous primary was relatively small, but invasive (pT2) tumor of the thoracic esophagus, was visible without lugol staining (Figure 2).

Considering low incidence of obstructive hypo-pharyngeal carcinomas and high sensitivity of intra-operative endoscopy in detection of second primary, there is no need to consider whether this diagnostic procedure is cost-effective or not. More important is that there are no complications related to the procedure. One of the things that might be of concern is potential contamination of the operating field during the procedure. In our experience there were no local infective complications associated with the procedure. Therefore, benefit of the procedure exceeds potential risk of local contamination.

In summary, it is reasonable to use intraoperative endoscopy as selective screening test in patients with obstructive hypopharyngeal carcinoma.

Co-first-author: Milos Bjelovic

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Shaha A, Hoover E, Marti J, Krespi Y. Is routine triple endo-scopy cost-effective in head and neck cancer. Am J Surg. 1988;155:750-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davidson J, Gilbert R, Irish J, Witterick I, Brown D, Birt D, Freeman J, Gullane P. The role of panendoscopy in the management of mucosal head and neck malignancy-a prospective evaluation. Head Neck. 2000;22:449-454; discussion 454-455. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Berg JW, Schottenfeld D, Ritter F. Incidence of multiple primary cancers. III. Cancers of the respiratory and upper digestive system as multiple primary cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;44:263-274. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wagenfeld DJ, Harwood AR, Bryce DP, van Nostrand AW, de Boer G. Second primary respiratory tract malignant neoplasms in supraglottic carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wagenfeld DJ, Harwood AR, Bryce DP, van Nostrand AW, DeBoer G. Second primary respiratory tract malignancies in glottic carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1883-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kohmura T, Hasegawa Y, Matsuura H, Terada A, Takahashi M, Nakashima T. Clinical analysis of multiple primary malignancies of the hypopharynx and esophagus. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morita M, Araki K, Saeki H, Sakaguchi Y, Baba H, Sugimachi K, Yano K, Sugio K, Yasumoto K. Risk factors for multicentric occurrence of carcinoma in the upper aerodigestive tract-analysis with a serial histologic evaluation of the whole resected-esophagus including carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:216-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miyazaki M, Ohno S, Futatsugi M, Saeki H, Ohga T, Watanabe M. The relation of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking to the multiple occurrence of esophageal dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2002;131:S7-S13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martins AS. Multicentricity in pharyngoesophageal tumors: argument for total pharyngolaryngoesophagectomy and gastric transposition. Head Neck. 2000;22:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumagai Y, Kawano T, Nakajima Y, Nagai K, Inoue H, Nara S, Iwai T. Multiple primary cancers associated with esophageal carcinoma. Surg Today. 2001;31:872-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kodama M, Kakegawa T. Treatment of superficial cancer of the esophagus: a summary of responses to a questionnaire on superficial cancer of the esophagus in Japan. Surgery. 1998;123:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gluckman JL, Crissman JD, Donegan JO. Multicentric squamous-cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Head Neck Surg. 1980;3:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McGuirt WF, Matthews B, Koufman JA. Multiple simul-taneous tumors in patients with head and neck cancer: a prospective, sequential panendoscopic study. Cancer. 1982;50:1195-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leipzig B, Zellmer JE, Klug D. The role of endoscopy in evaluating patients with head and neck cancer. A multi-institutional prospective study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:589-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shapshay SM, Hong WK, Fried MP, Sismanis A, Vaughan CW, Strong MS. Simultaneous carcinomas of the esophagus and upper aerodigestive tract. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88:373-377. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Akyiama H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus. Surgery for cancer of the esophagus. Baltimore: William&Wilkins 1990; 151-152. |

| 17. | Halpert RD, Feczko PJ. Role of radiology in the diagnosis and staging of gastric malignancy. Endoscopy. 1993;25:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wu LF, Wang BZ, Feng JL, Cheng WR, Liu GR, Xu XH, Zheng ZC. Preoperative TN staging of esophageal cancer: comparison of miniprobe ultrasonography, spiral CT and MRI. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:219-224. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Greenberg J, Durkin M, Van Drunen M, Aranha GV. Computed tomography or endoscopic ultrasonography in preoperative staging of gastric and esophageal tumors. Surgery. 1994;116:696-701; discussion 701-702. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Weaver SR, Blackshaw GR, Lewis WG, Edwards P, Roberts SA, Thomas GV, Allison MC. Comparison of special interest computed tomography, endosonography and histopathological stage of oesophageal cancer. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kienle P, Buhl K, Kuntz C, Dux M, Hartmann C, Axel B, Herfarth C, Lehnert T. Prospective comparison of endoscopy, endosonography and computed tomography for staging of tumours of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. Digestion. 2002;66:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Korst RJ, Altorki NK. Imaging for esophageal tumors. Thorac Surg Clin. 2004;14:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Moretó M. Diagnosis of esophagogastric tumors. Endoscopy. 2005;37:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Panosetti E, Luboinski B, Mamelle G, Richard JM. Multiple synchronous and metachronous cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract: a nine-year study. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1267-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ferguson JL, DeSanto LW. Total pharyngolaryngectomy and cervical esophagectomy with jejunal autotransplant reconstruction: complications and results. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:911-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Julieron M, Germain MA, Schwaab G, Marandas P, Bourgain JL, Wibault P, Luboinski B. Reconstruction with free jejunal autograft after circumferential pharyngolaryngectomy: eighty-three cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:581-587. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Flynn MB, Banis J, Acland R. Reconstruction with free bowel autografts after pharyngoesophageal or laryngopharyngoesophageal resection. Am J Surg. 1989;158:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shiozaki H, Tahara H, Kobayashi K, Yano H, Tamura S, Imamoto H, Yano T, Oku K, Miyata M, Nishiyama K. Endoscopic screening of early esophageal cancer with the Lugol dye method in patients with head and neck cancers. Cancer. 1990;66:2068-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yokoyama A, Ohmori T, Makuuchi H, Maruyama K, Okuyama K, Takahashi H, Yokoyama T, Yoshino K, Hayashida M, Ishii H. Successful screening for early esophageal cancer in alcoholics using endoscopy and mucosa iodine staining. Cancer. 1995;76:928-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |