Published online Jul 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4536

Revised: March 12, 2006

Accepted: February 18, 2006

Published online: July 28, 2006

AIM: To assess the incidence of and risk factors for gallstone disease (GSD) among type 2 diabetics in Kinmen, Taiwan.

METHODS: A screening program for GSD was performed by two specialists who employed real-time abdominal ultrasound to examine the abdominal region after patients had fasted for at least eight hours. Screening, which was conducted in 2001, involved 848 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. After exclusion of 63 subjects with prevalent GSD, 377 participants without GSD were invited in 2002 for a second round of screening. A total of 281 (74.5%) subjects were re-examined.

RESULTS: Among the 281 type 2 diabetics who had no GSD at the first screening, 10 had developed GSD by 2002. The incidence was 3.56% per year (95% CI: 1.78% per year-6.24% per year). Using a Cox regression model, age (RR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.00-1.14), waist circumference (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.01-1.29), and ALT (RR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.01-1.26) appeared to be significantly correlated with development of GSD.

CONCLUSION: Older age is a known risk factor for the development of GSD. Our study shows that greater waist circumference and elevated ALT levels are also associated with the development of GSD among type 2 diabetics in Kinmen.

- Citation: Tung TH, Ho HM, Shih HC, Chou P, Liu JH, Chen VT, Chan DC, Liu CM. A population-based follow-up study on gallstone disease among type 2 diabetics in Kinmen, Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(28): 4536-4540

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i28/4536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4536

Gallstone disease (GSD), a digestive disorder with multifactorial origins, is very common worldwide. Within the past few years ultrasonographic studies have provided estimates of GSD prevalence and of predisposing factors in various populations[1-5]. Although some controversy exists regarding the association between diabetes and GSD, population-based epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that diabetic subjects have an increased morbidity of GSD[6-8]. Moreover, our previous report showed that the prevalence of overall GSD among type 2 diabetics is higher than in other general Chinese populations when using the same methods for GSD assessment[5].

Previous study had explored the prevalence of GSD and associated factor among type 2 diabetics[5], and cross-sectional studies provided useful information of disease prevalence, however, they did not present the incidence or new cases in the study population. One must re-examine the population after a period of time in order to determine incidence and causal relationships between risk factors and disease. From a preventive medicine viewpoint, primary prevention of GSD should focus on risk factors responsible for the occurrence of GSD. To explore the incidence of and risk factors for GSD is essential to prevent its development and the cholecystectomy caused by this complication, which is often insidious in nature. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a population-based study which estimates GSD incidence. This is in part due to the fact that more than half of subjects with GSD are unaware of their condition and diagnosed cases seem to represent a selected group based on clinical studies[8]. Recently, however, a few population-based prospective studies have described the incidence and temporal relationship between the development of GSD and various risk factors among type 2 diabetics in Taiwan. The present study was conducted to explore the incidence and risk factors of GSD among type 2 diabetics in Kinmen, Taiwan based on a one-year follow-up period using real time abdominal ultrasound.

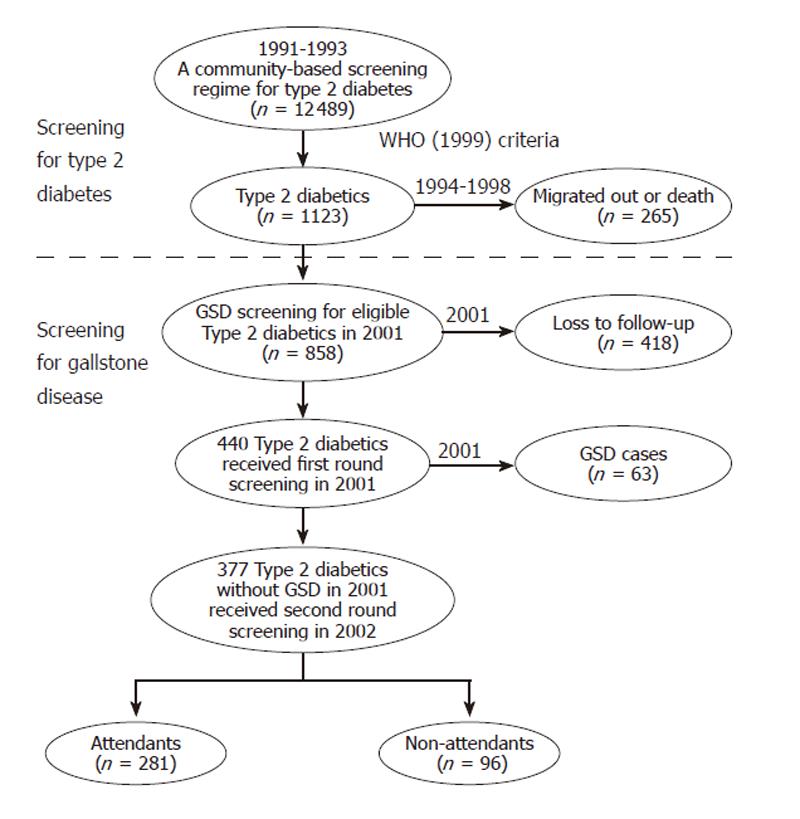

Figure 1 shows the procedures for GSD screening between 2001 and 2002. Data used in this study were derived from a population-based screening for type 2 diabetes targeted to subjects aged 30 years or more in Kinmen, Taiwan, between January 1991 and December 1993. The details of the study design and execution have been described in full elsewhere[9]. The identification of type 2 diabetes was based on the WHO definition in 1985[10], namely, subjects with a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 140 mg/dL or a 2 h postload glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL. Subjects with a history of type 2 diabetes and who had received medication were defined as known cases. However, in the GSD screening done in 2001, even patients who fulfilled the criteria of the revised WHO 1999 were enrolled. That is, additional patients with FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL and <140 mg/dL in 1991 to 1993 were also recruited[11]. A total of 1123 type 2 diabetics aged 30 and over were identified based on face-to-face interviews carried out by the Yang-Ming Crusade, a volunteer organization of well-trained medical students of National Yang-Ming University. After exclusion of those who migrated or died, the remaining 858 type 2 diabetics formed a cohort to receive first round abdominal ultrasound in 2001. A total of 440 (51.3%) subjects were examined in first screening for GSD. Sixty-three out of 440 type 2 diabetics were diagnosed with GSD. The overall prevalence of GSD was 14.4%, including single stone 8.0% (n = 35), multiple stones 3.2% (n = 14), and cholecystectomy 3.2% (n = 14) [5]. The 377 diabetics without GSD screened in 2001 were then invited by telephone calls or invitation letters in 2002 to receive a second round of abdominal examinations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the GSD screening[5].

In the present study, fasting blood samples were drawn by public health nurses. Overnight fasting serum and plasma samples (preserved with EDTA and NaF) were collected and kept frozen (-20°C) until analysis for measurements of biochemistry markers. FPG concentrations were determined using the hexokinase-glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method with a glucose (HK) reagent ldt (Gilford, Cberlin, OH). The BMI, waist circumference, uric acid, and HbA1c data were also collected during the GSD screening in 2001. The duration of type 2 diabetes in patients who were previously diagnosed with the disease was confirmed by the questionnaire. In addition, the screening protocol for GSD was performed in 2001 and 2002. GSD was diagnosed by two specialists using real-time abdominal ultrasound to examine the abdominal region after participants had fasted for at least 8 h. GSD was identified based on the presence of “movable hyperechoic material with acoustic shadow. Cases of GSD were classified as follows: single gallbladder stone, multiple gallbladder stones, and cholecystectomy, excluding gallbladder polyps. Cases were identified as any type of GSD among type 2 diabetics.

In order to set up a consistent diagnosis of GSD among two specialists, the Kappa statistic was used to assess inter-observer reliability among study specialists. A pilot study was performed with a randomly selected cohort (n = 50) of type 2 diabetics other than the study subjects. Our pilot study on inter-observer reliability showed a Kappa value for diagnosis of GSD of 0.77 (95%CI: 0.50-0.96).

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software. The incidence of GSD was determined per year based on the ratio of the observed number of cases to the total number of patient-years at risk. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for incidence were calculated using the Poisson distribution. In the univariate analysis, a t-test was applied for continuous variables. Multiple Cox regression was used to investigate the independence of factors associated with development of GSD. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results are presented as

mean ± SD.

Of 377 type 2 diabetics without GSD in 2001, 281 subjects attended the second round of abdominal ultrasound examinations in 2002. The overall attendance rate was thus about 74.5%. Subjects were considered as censored cases if the outcomes were not available. Table 1 shows that females had higher attendance rates than males (76.2% versus 72.5%), and old people (50-59 and over 70 year of age) had a slightly lower attendance rate than other age groups.

| Variable | Eligible population | Screened population | Attendance rate | |

| n | n | (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 167 | 121 | 72.5 | |

| Female | 210 | 160 | 76.2 | |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 40-49 | 43 | 33 | 76.7 | |

| 50-59 | 87 | 56 | 64.4 | |

| 60-69 | 134 | 111 | 82.8 | |

| 70+ | 113 | 81 | 71.7 | |

| Total | 377 | 281 | 74.5 | |

Table 2 presents gender-specific and age-specific one-year incidences of GSD. Overall incidence of GSD was 3.56% per year (95%CI: 1.78% per year-6.24% per year). This incidence shows a clear trend with age (P = 0.04) with values increasing monotonically: from 0% per year at age 40-49 years to 3.57% per year at age 50-59 years, 3.60% per year at age 60-69 years to 4.94% per year at older ages. There was no consistent pattern by age group. Females had a slightly higher incidence (5.00% per year versus 1.65% per year, P = 0.12) than males, although the gender difference was not statistically significant.

| Variable | Incidence of any gallstone disease | |||

| No. of no GSD at first screening | New cases | Incidence density (% per year) (95%CI) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 121 | 2 | 1.65 | |

| (0.03-5.10) | ||||

| Female | 160 | 8 | 5 | |

| (2.29-9.31) | ||||

| P-value | 0.12 | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 40-49 | 33 | 0 | 0 | |

| (-) | ||||

| 50-59 | 56 | 2 | 3.57 | |

| (0.06-11.03) | ||||

| 60-69 | 111 | 4 | 3.6 | |

| (1.12-8.37) | ||||

| 70+ | 81 | 4 | 4.94 | |

| (1.53-11.47) | ||||

| P-value | 0.04 | |||

| Total | 281 | 10 | 3.56 | |

| (1.78-6.24) | ||||

Table 3 shows the risk factors for the development of GSD in type 2 diabetics by univariate analysis. The risk factors that were significantly related to the development of GSD included age (t, T = 1.98, P = 0.04), BMI (T = 3.18, P = 0.01), waist circumference (T = 8.16, P = 0.0001), total cholesterol (T = 4.94, P = 0.0001), AST (T = 2.83, P = 0.01), and ALT (T = 2.69, P = 0.01).

| Variables | Development of gallstone disease | |||

| Yes | No | P value | Definitions of | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | for t test | disease condition | |

| Age (yr) | 69.90 ± 8.79 | 63.11 ± 10.72 | 0.04 | - |

| Duration of diabetes (yr) | 9.60 ± 0.84 | 9.44 ± 1.59 | 0.59 | - |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 148.50 ± 18.45 | 144.94 ± 39.35 | 0.58 | ≥ 126 mg/dL |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.19 ± 0.93 | 8.33 ± 2.05 | 0.69 | ≥ 7% |

| Systolic blood pressure(mmHg) | 152.49 ± 13.91 | 145.08 ± 16.35 | 0.16 | ≥ 140 mmHg |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 89.55 ± 9.40 | 86.74 ± 9.52 | 0.36 | ≥ 90 mmHg |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 26.57 ± 1.07 | 25.36 ± 2.87 | 0.01 | ≥ 27 kg/m2 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89.74 ± 7.95 | 85.23 ± 7.52 | 0.000 | ≥ 90 cm for males or ≥ 80 cm for females |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 220.09 ± 20.57 | 210.99 ± 26.82 | 0.000 | ≥ 200 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 178.50 ± 38.95 | 144.28 ± 66.72 | 0.11 | ≥ 200 mg/dL |

| AST (U/L) | 25.40 ± 6.95 | 22.40 ± 8.15 | 0.01 | ≥ 40 U/L |

| ALT (U/L) | 31.36 ± 9.34 | 22.39 ± 10.28 | 0.01 | ≥ 40 U/L |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.07 ± 1.20 | 5.94 ± 1.29 | 0.76 | ≥ 7 mg/dL for males or ≥ 6 mg/dL for females |

To assess the independence of the contributions of these factors to the development of GSD, the significant variables from univariate analysis for GSD were further examined using a Cox regression model including age, BMI, waist circumference, total cholesterol, AST, and ALT. As Table 4 shows, age (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 1.00-1.14), waist circumference (RR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.01-1.29), and ALT (RR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.01-1.26) appeared to be independently correlated with development of GSD.

| Variables | Development of gallstone disease (yes vs no) | |

| Relative risk | (95% CI) | |

| Sex (female vs male) | 2.60 | 0.52-13.11 |

| Age (yr) | 1.07 | 1.00-1.14 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 1.03 | 0.57-1.34 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 1.12 | 1.01-1.29 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.01 | 0.98-1.03 |

| AST (U/L) | 0.91 | 0.77-1.07 |

| ALT (U/L) | 1.13 | 1.01-1.26 |

Abdominal ultrasound for GSD screening is viewed as a robust method. Previous clinical studies have shown reliable positive (0.99-1.00) and negative (0.90-0.96) predictive values of ultrasonographic diagnosis[12]. In the present study, the annual incidence of overall GSD was higher than that in other general population-based studies[12-15], implying that type 2 diabetes might be a positive risk factor for GSD development. Possible pathogenic reasons are that type 2 diabetes combined with GSD might induce acute cholecystitis more often and have a higher probability of progression to septicemia than does gallbladder dysfunction in non-diabetic patients[16], and late-onset diabetic patients have a higher lithogenic bile index than non-diabetics after adjustment for sex and age[17]. In addition, hyperglycemia in diabetic subjects might exert effects on gallbladder motility[18].

An association between GSD and use of exogenous estrogens was confirmed[19]. The lithogenic effects of estrogen are mediated in part by an increase in bile cholesterol saturation[19]. However, previous studies showed that cholesterol GSD is common in Western populations whereas pigment GSD is major components in Taiwan[1]. Unlike result for cholesterol GSD, our results did not show a causal relationship between female sex and development of pigment GSD. The different findings for Orientals from those shown for Occidentals suggest that cholesterol GSD has not yet become a major GSD component in Taiwanese diabetic populations.

Using both univariate analysis and a multiple Cox regression model, our study also demonstrated that age is a significant risk factor for the development of GSD. This result is not concordant with results from other studies that had longer screening intervals[8,13,15]. Larger amounts of cholesterol secreted by the liver and decreases in the catabolism of cholesterol to bile acid were observed in the elderly[20]. Although the long-term exposure to many other risk factors in the elderly might account for their increased chance of developing GSD[5], age still remained a major factor leading to GSD development, irrespective of locality, standard of living, or after adjustment for other demographic and clinical characteristics in the multivariate analysis.

Several population-based studies demonstrated that liver cirrhosis represents a strong risk factor for GSD[21,22]. The annual incidence of GSD in patients with cirrhosis appears to be about eight times higher than in the general population[21]. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) has, for some time, been viewed as a sensitive indicator of liver-cell injury[23]. Currently, the determination of serum ALT levels constitutes the most-frequently applied test for the identification of patients suffering from liver disease. This parameter also acts as a surrogate marker for disease severity and/or as an index of hepatic activity[24]. Our results showing that elevated ALT levels constitute higher risk of GSD development suggest that appropriate integrated diagnosis and therapy in the early stage of liver dysfunction might eventually enable us to prevent incident GSD. Instead of being a sign of more serious liver disease like liver cirrhosis, further studies should be conducted to explore the possibility of whether elevated ALT levels is an indicator for GSD because it indicates a fatty liver (and thus a high BMI), and early stage of chronic liver disease.

Obesity could raise the saturation of bile by increasing biliary secretion of cholesterol, the latter probably depending on a higher synthesis of cholesterol in obese subjects[25]. Being overweight at baseline was strongly associated with the incidence of GSD which was also suggested in epidemiologic studies[13]. In this follow-up study, we found that a higher waist circumference rather than a higher BMI was significantly and positively associated with GSD development. Thus abdominal obesity might be more important than BMI for identifying diabetics at high risk of GSD. One possible reason is that due to a high correlation between BMI and waist circumference (r = 0.64), waist circumference might explain the effect of BMI on GSD development in type 2 diabetic subjects. Another possible reason is that a large waist circumference might be an unambiguous indicator of excess body fat, except in the presence of abdominal tumors or ascites, and might be a better estimate of overall body fat than is BMI. In addition, from the biological perspective, BMI becomes primarily a surrogate of lean body mass when BMI and height-adjusted waist circumference are included in the same model, because the variation in BMI attributable to adiposity is essentially controlled by the height-adjusted waist circumference variable[14]. Nevertheless, further epidemiological and etiologic investigations are needed to explore the pathophysiological mechanism underlying gender-related differences in waist circumference and GSD among diabetics.

Although using a follow-up study design can clarify the temporal relationship of potential risk factors and the development of GSD, there are some limitations in the present study. First, the characteristics pertinent to the risk of type 2 diabetes for study subjects were not significantly different from non-respondents (except for age), indicating that subjects who did not return for follow-up might have more severe GSD. Also, we assumed that all the new GSD cases occurred in 2002. Since additional GSD cases could occur in subsequent years, the incidence of GSD may be underestimated. Second, all the patients had diabetes in the study population, therefore, an evaluation of the extent of GSD incidence in subjects without diabetes was difficult. Third, we did not attempt to estimate the incidence of gallstone formation but rather the incidence of newly screened GSD. Our analysis only focused on clinically relevant GSD. Fourth, due to a shorter follow-up period, we did not have a large enough sample size to estimate the “true” effects between potential risk factors and the incidence of GSD. Further long-term studies should be conducted to explore the morbidity of GSD and plausible biological mechanisms underlying its development.

In conclusion, our reports show that the incidence of GSD is 3.56% per year. Significant risk factors for the development of GSD include not only older age, but also, higher waist circumference and elevated ALT levels among type 2 diabetics.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Chen CY, Lu CL, Huang YS, Tam TN, Chao Y, Chang FY, Lee SD. Age is one of the risk factors in developing gallstone disease in Taiwan. Age Ageing. 1998;27:437-441. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | De Santis A, Attili AF, Ginanni Corradini S, Scafato E, Cantagalli A, De Luca C, Pinto G, Lisi D, Capocaccia L. Gallstones and diabetes: a case-control study in a free-living population sample. Hepatology. 1997;25:787-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kono S, Shinchi K, Todoroki I, Honjo S, Sakurai Y, Wakabayashi K, Imanishi K, Nishikawa H, Ogawa S, Katsurada M. Gallstone disease among Japanese men in relation to obesity, glucose intolerance, exercise, alcohol use, and smoking. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sasazuki S, Kono S, Todoroki I, Honjo S, Sakurai Y, Wakabayashi K, Nishiwaki M, Hamada H, Nishikawa H, Koga H. Impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes mellitus, and gallstone disease: an extended study of male self-defense officials in Japan. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu CM, Tung TH, Liu JH, Lee WL, Chou P. A community-based epidemiologic study on gallstone disease among type 2 diabetics in Kinmen, Taiwan. Dig Dis. 2004;22:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shaw SJ, Hajnal F, Lebovitz Y, Ralls P, Bauer M, Valenzuela J, Zeidler A. Gallbladder dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:490-496. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haffner SM, Diehl AK, Valdez R, Mitchell BD, Hazuda HP, Morales P, Stern MP. Clinical gallbladder disease in NIDDM subjects. Relationship to duration of diabetes and severity of glycemia. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1276-1284. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jensen KH, Jørgensen T. Incidence of gallstones in a Danish population. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:790-794. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jensen KH, Jorgensen T. Incidence of gallstones in a Danish population. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:790-794. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | World Health Organization. Diabetes Mellitus: Report of a WHO Study Group. Geneva, World Health Organization,1985;(Tech. Rep. Ser., no.727). . |

| 12. | Mogensen NB, Madsen M, Stage P, Matzen P, Malchow-Moeller A, Lejerstofte J, Uhrenholdt A. Ultrasonography versus roentgenography in suspected instances of cholecystolithiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;159:353-356. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Misciagna G, Leoci C, Guerra V, Chiloiro M, Elba S, Petruzzi J, Mossa A, Noviello MR, Coviello A, Minutolo MC. Epidemiology of cholelithiasis in southern Italy. Part II: Risk factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:585-593. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Prospective study of abdominal adiposity and gallstone disease in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:38-44. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lowenfels AB, Velema JP. Estimating gallstone incidence from prevalence data. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:984-986. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shreiner DP, Sarva RP, Van Thiel D, Yingvorapant N. Gallbladder function in diabetic patients. J Nucl Med. 1986;27:357-360. [PubMed] |

| 17. | de Leon MP, Ferenderes R, Carulli N. Bile lipid composition and bile acid pool size in diabetes. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:710-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | de Boer SY, Masclee AA, Lamers CB. Effect of hyperglycemia on gastrointestinal and gallbladder motility. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1992;194:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bennion LJ, Grundy SM. Risk factors for the development of cholelithiasis in man (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1978;299:1221-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Méndez-Sánchez N, Cárdenas-Vázquez R, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Uribe M. Pathophysiology of cholesterol gallstone disease. Arch Med Res. 1996;27:433-441. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Fornari F, Imberti D, Squillante MM, Squassante L, Civardi G, Buscarini E, Cavanna L, Caturelli E, Buscarini L. Incidence of gallstones in a population of patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1994;20:797-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Del Olmo JA, Garcia F, Serra MA, Maldonado L, Rodrigo JM. Prevalence and incidence of gallstones in liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1061-1065. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kaplan MM. Alanine aminotransferase levels: what's normal. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1266-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 25. | Bouchier IAD. Gallstones: formation and epidemiology. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. Edinburgh: Churchill linvingstone 1998; 503-516. |