Published online Jul 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4093

Revised: August 16, 2005

Accepted: August 26, 2005

Published online: July 7, 2006

Situs inversus abdominus with rotational anomaly of the intestines is an extremely rare condition. Although intestinal malrotation has been recognized as a cause of obstruction in infants and children and may be complicated by intestinal ischaemia, it is very rare in adults. When it occurs in the adult patient, it may present acutely as bowel obstruction or intestinal ischaemia or chronically as vague intermittent abdominal pain. Herein, we present an acute presentation of a case of situs inversus abdominus and intestinal malrotation with Ladd’s band leading to infarction of the intestine in a 32 year old woman.

- Citation: Mallick IH, Iqbal R, Davies JB. Situs inversus abdominus and malrotation in an adult with Ladd’s band formation leading to intestinal ischaemia. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(25): 4093-4095

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i25/4093.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4093

Situs inversus abdominus is an extremely rare condition when it occurs in adults. It may present with vague abdominal pain or with intestinal obstruction or with intestinal ischaemia. We describe a patient with situs inversus abdominus who presented to us acutely with intestinal ischaemia.

A 32-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with severe cramping and generalized abdominal pain of 2 d duration. This cramping pain occurred every 2 to 3 h and was 30 to 40 min in duration. She vomited several times which was bilious in nature. Her last bowel movement was 2 d prior, and it was described as normal. Her past medical history included mitral valvuloplasty for rheumatic heart disease. She had also developed cardiac cirrhosis secondary to rheumatic heart disease. There was no history of previous abdominal surgery and denied alcohol or tobacco use.

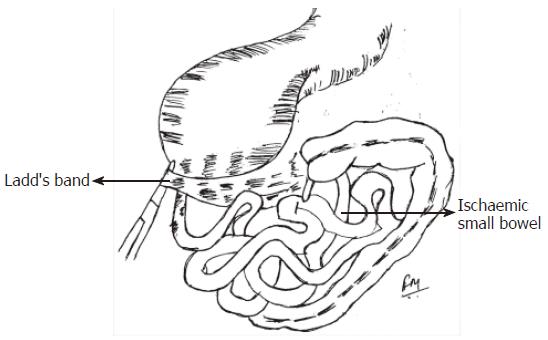

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were pulse 90, blood pressure 126/67, temperature 37°C, and respiratory rate was 16. The abdomen was not distended. She exhibited no peritoneal signs; however, mild diffuse tenderness to deep palpation was appreciated. Normal bowel sounds were present on auscultation. Her rectal examination was normal. Haemoglobin, white blood cell count, basic biochemistry panel and arterial blood gases were all within normal values. Abdominal X-rays did not reveal any features of obstruction. Chest radiography did not reveal any signs of perforation of a hollow viscus. A prompt computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed which demonstrated situs inversus abdominus and free air intraperitoneally suggesting perforation of a hollow viscus (Figure 1). She was taken to theatre urgently for a laparotomy, which revealed malrotation of the intestines with complete situs inversus. The entire small bowel was found to be of doubtful viability and there was a presence of Ladd’s band running from the ileocaecal valve to the duodenojejunal flexure around which the small bowel had rotated (Figure 2). The Ladd’s band was divided which improved the perfusion of the bowel to a reasonable extent and a decision was made to pack the wound and have a second look laparotomy in the next 12 h. Postoperatively she was nursed in the intensive care unit where she developed endotoxic shock and multiple organ failure. At the second laparotomy, the entire small and the large bowel were infarcted which was deemed incompatible with life. A decision was made to close the abdomen and the patient died in the next few hours in the intensive care unit.

Situs inversus abdominus (SIA) is an uncommon anomaly with an incidence varying from 1in 4000 to 1 in 20 000 live births[1]. Acute surgical emergencies complicating SIA are extremely rare in the adult and very few cases are reported in the English literature[2,3] . Situs inversus was first described by Aristotle in animals and by Fabricius in humans[4]. Congenital anomalies of intestinal rotation are often seen in infants and children; however, they are uncommon in adults. Approximately 85% of malrotation cases present in the first 2 wk of life[5].

A brief knowledge of intestinal embryology is necessary in order to understand the rotation of the intestine and its anomalies. The embryo’s gut is in the form of a straight tube at the fourth week of intra-uterine life. Approximately during the fifth week, a vascular pedicle develops and the gut can be divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The superior mesenteric artery supplies blood to the midgut. The midgut is defined by a rapidly enlarging loop with the superior mesenteric artery running out to its apex. The cephalad portion of the loop gives rise to the first six metres of small intestine, and the remainder of the loop forms the distal small bowel and colon up to the splenic flexure. Intestinal rotation primarily involves the midgut. The rotation of intestinal development has been divided into 3 stages. Stage I occurs in wk 5 to 10. It includes extrusion of the midgut into the extra-embryonic cavity, a 90° anti-clockwise rotation, and return of the midgut into the fetal abdomen. Stage II occurs in week 11 and involves further anti-clockwise rotation within the abdominal cavity completing a 270° rotation. This rotation brings the duodenal “C” loop behind the superior mesenteric artery with the ascending colon to the right, the transverse colon above, and descending colon to the left. Stage III involves fusion and anchoring of the mesentery. The caecum descends, and the ascending and descending colon attach to the posterior abdominal wall.

Intestinal anomalies can be classified by the stage of their occurrence[6]. Stage I anomalies include omphaloceles caused by failure of the gut to return to the abdomen. Stage II anomalies include nonrotation, malrotation, and reversed rotation. Stage III anomalies include an unattached duodenum, mobile caecum, and an unattached small bowel mesentery.

Many remain asymptomatic through life and the anomaly is discovered only at autopsy. Some may present with chronic and unexplained abdominal discomfort, and even fewer may report acute episodes of agonizing abdominal pain. Symptoms can arise from acute or chronic intestinal obstruction that may be caused by the presence of abnormal peritoneal bands (Ladd’s bands) or a volvulus.

Malrotation of the colon is estimated to occur in 0.2% to 0.5% of the adults and is significant clinically in only a small portion of them. There are no typical set of symptoms that are diagnostic of this clinical problem. The location of the pain may vary from epigastric to left upper quadrant. Often occurs postprandially and may last several minutes up to 1 h. Patients are frequently followed for a long period before undergoing surgery. The difficulty of diagnosis lies in both the absence of specific physical findings and the low adult frequency. Symptoms in the adult patient are often mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, biliary and pancreatic disease, and psychiatric disorders[7].

The diagnosis of rotational anomaly can be made by radiographic studies[8] . In the absence of volvulus, a plain x-ray of the abdomen is of little diagnostic value. The absence of caecal gas shadow or the localization of small intestinal loops predominately in the right side should arouse the suspicion of malrotation[9]. Malrotation can be diagnosed on CT by the anatomic location of a right-sided small bowel, a left-sided colon and an abnormal relationship of the superior mesenteric vessels. Nichols and Li described the abnormal position of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) wherein the SMV was situated to the left of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) instead of to the right on CT scan in patients with malrotation[10].

The classic treatment for incomplete intestinal rotation is the Ladd procedure, which entails mobilization of the right colon, division of Ladd’s bands and mobilization of the duodenum, division of adhesions around the SMA to broaden the mesenteric base, and an appendectomy. This procedure was originally described by Ladd [11].

In conclusion, adult presentation of situs inversus abdominus with intestinal malrotation is a difficult diagnosis because of the rare incidence of the disorder. These patients often present with chronic abdominal pain or with ischaemia as exemplified by our case. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

The authors would like to thank Mrs Femina Mallick for her assistance in the illustration.

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Alpini G E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Budhiraja S, Singh G, Miglani HP, Mitra SK. Neonatal intestinal obstruction with isolated levocardia. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1115-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Janchar T, Milzman D, Clement M. Situs inversus: emergency evaluations of atypical presentations. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:349-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Contini S, Dalla Valle R, Zinicola R. Suspected appendicitis in situs inversus totalis: an indication for a laparoscopic approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:393-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Blegen HM. Surgery in Situs Inversus. Ann Surg. 1949;129:244-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | WANG CA, WELCH CE. ANOMALIES OF INTESTINAL ROTATION IN ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS. Surgery. 1963;54:839-855. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Stinger DA. Pediatric Gastrointestinal Imaging. Philadelphia: BC Decker 1989; 235–239. |

| 7. | Fukuya T, Brown BP, Lu CC. Midgut volvulus as a complication of intestinal malrotation in adults. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:438-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torres AM, Ziegler MM. Malrotation of the intestine. World J Surg. 1993;17:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Garg P, Singh M, Marya SK. Intestinal malrotation in adults. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1991;10:103-104. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Nichols DM, Li DK. Superior mesenteric vein rotation: a CT sign of midgut malrotation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:707-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ladd WE. Congenital obstruction of the duodenum in children. N Engl J Med. 1932;206:277-283. [DOI] [Full Text] |