Published online Jun 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3597

Revised: January 14, 2006

Accepted: January 24, 2006

Published online: June 14, 2006

AIM: To analyze the importance in predicting patients risk of mortality due to upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding under today's therapeutic regimen.

METHODS: From 1998 to 2001, 121 patients with the diagnosis of UGI bleeding were treated in our hospital. Based on the patients’ data, a retrospective multivariate data analysis with initially more than 270 single factors was performed. Subsequently, the following potential risk factors underwent a logistic regression analysis: age, gender, initial hemoglobin, coumarines, liver cirrhosis, prothrombin time (PT), gastric ulcer (small curvature), duodenal ulcer (bulbus back wall), Forrest classification, vascular stump, variceal bleeding, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, RBC substitution, recurrent bleeding, conservative and surgical therapy.

RESULTS: Seventy male (58%) and 51 female (42%) patients with a median age of 70 (range: 21-96) years were treated. Their in-hospital mortality was 14%. While 12% (11/91) of the patients died after conservative therapy, 20% (6/30) died after undergoing surgical therapy. UGI bleeding occurred due to duodenal ulcer (n = 36; 30%), gastric ulcer (n = 35; 29%), esophageal varicosis (n = 12; 10%), Mallory-Weiss syndrome (n = 8; 7%), erosive lesions of the mucosa (n = 20; 17%), cancer (n = 5; 4%), coagulopathy (n = 4; 3%), lymphoma (n = 2; 2%), benign tumor (n = 2; 2%) and unknown reason (n = 1; 1%). A logistic regression analysis of all aforementioned factors revealed that liver cirrhosis and duodenal ulcer (bulbus back wall) were associated risk factors for a fatal course after UGI bleeding. Prior to endoscopy, only liver cirrhosis was an assessable risk factor. Thereafter, liver cirrhosis, the location of a bleeding ulcer (bulbus back wall) and patients’ gender (male) were of prognostic importance for the clinical outcome (mortality) of patients with a bleeding ulcer.

CONCLUSION: Most prognostic parameters used in clinical routine today are not reliable enough in predicting a patient’s vital threat posed by an UGI bleeding. Liver cirrhosis, on the other hand, is significantly more frequently associated with an increased risk to die after bleeding of an ulcer located at the posterior duodenal wall.

- Citation: Schemmer P, Decker F, Dei-Anane G, Henschel V, Buhl K, Herfarth C, Riedl S. The vital threat of an upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Risk factor analysis of 121 consecutive patients. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(22): 3597-3601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i22/3597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3597

Acute bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Over the last decades, mortality after UGI bleeding has been reported to range between 8% and 14% of cases[1-8]. Selected groups, i.e. patients who underwent surgical therapy for UGI bleeding, die at a risk of about 21%[9].

Despite improved diagnostic measures, emergency endoscopy[10], improved conservative and surgical treatment[5,11], mortality after UGI bleeding remains high[1]. An increase in the number of high-risk patients with reduced ability to compensate for the consequences of bleeding may be one of the reasons for this phenomenon[11,12]. Further, UGI bleeding is the most common emergency in gastroenterology, with an incidence of about 50 to 150 bleeding episodes per 100 000 inhabitants per year[4,11,13,14].

Numerous prognostic factors have been described in literature to be associated with a lethal outcome; however, to date, it remains unclear whether a single or a combination of these parameters is valid in predicting the vital threat of a patient with an UGI bleeding[1,13,15,16]. Some factors were assessed for decision making on early surgical therapy in patients with bleeding ulcers[5,17]. However, they have not become clinical routine due to their poor reliability.

There are very few studies which report on risk factors for an increased threat after UGI bleeding based on multivariate analysis[1]. Thus, our retrospective study was designed to evaluate published risk factors for their value in predicting the threat to patients with UGI bleeding.

A database was established retrospectively using infor-mation on consecutive admitted patients, with evidence of UGI bleeding treated in the Department of General Surgery, Ruprecht-Karls-University, Heidelberg, Germany during 4 consecutive years from January 1st, 1998 to December 31st, 2001.

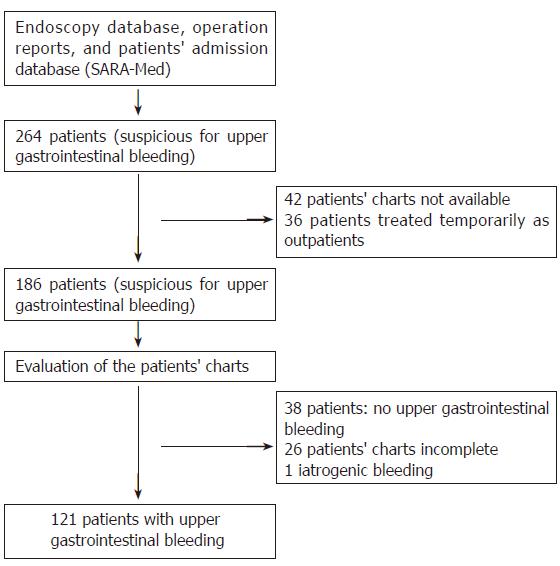

The patients were identified with endoscopy, patients’ admission (electronic patients chart SARA-Med), and an operation protocol database. Within the evaluated 4 years, a total of 264 patients with the suspicion of UGI bleeding were found (Figure 1). Thirty-six of these were treated temporarily in the outpatient clinic. In these cases no hospitalization was necessary. Further 38 patients were excluded from analysis since their charts could not show enough evidence of an UGI bleeding. Forty-two patients’ charts were not available for analysis. Thus, these patients were excluded from further analysis. Twenty-six cases have not been documented in the way needed for an appropriate analysis. Since a gap-free documentation is needed for statistics, a total of 65 patients were excluded from this study. Moreover, patients were excluded from this study if UGI bleeding was due to previous surgery or endoscopic intervention (n = 1).

MedLine was searched for gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, bleeding peptic ulcer, peptic ulcer hemorrhage, bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract, stigmata of hemorrhage, prediction of mortality, emergency endoscopy, predictive factors, and further hemorrhage. Fifty-five publications on prognostic factors and risk factors of UGI bleeding were found, including papers mentioned in their references. Subsequently, factors (i.e., renal failure, heart failure, diabetes mellitus and others; n = 79) were classified according to the frequency of their appearance. Factors which fulfill at least one of the following conditions have been included: Factors which have been mentioned at least twice in the context of risks and prognosis for mortality, recurrence of bleeding, failed endoscopic therapy or necessity of surgery and a significant correlation between the parameter and mortality after univariate or multivariate analysis.

During various stages of therapy, different information was available. Thus, analysis was performed at the time of admission, right after endoscopy and after completed therapy. The following information on the patients were given and analyzed:

At admission: Age, gender, medication [i.e. coumarines, acetyl salicylic acid (ASS), non-steroidal antirheumatics (NSA)], liver disease, laboratory findings (i.e. hemoglobin, PT) were recorded.

At endoscopy: In addition to information obtained at admission, the localization, the Forrest classification and the presence of a vascular stump were elucidated.

At the end of therapy: In addition to the aforemen-tioned information, the number of blood units transfused, frequency of re-bleeding and the number of operations were recorded.

The in-hospital survival was chosen as the endpoint. It was analyzed as to how the probability of survival depends on covariates by means of stepwise logistic regression[18] where the significance level for entry of a covariate was chosen as 0.2 and the significance level for staying was chosen as 0.15.

Only parameters which were documented for all of our 121 patients with a special focus on clinical relevant parameters published before were analyzed. The possible covariates which were considered are: gender, age (dichotomised at 70 years), medication (ASS, NSA, and coumarines), liver cirrhosis, gastric ulcer (small curvature), duodenal ulcer (bulbus back wall), varices, Forrest classification, vascular stump, prothrombin time (dichotomised at 50%), hemoglobin concentration (dichotomised at 60 g/L), transfused blood units (dichotomised at 6 units), recurrence of bleeding and operations.

Three models were applied. The first considered the knowledge of covariates before the first gastroduodenoscopy. The second model takes only the patients with bleeding in the ulcers where the Forrest classification is valid into account, whereas the third model considers the covariates which are known after the termination of bleeding[18].

The total of 121 patients with UGI bleeding included in our analysis comprised of 70 males (58%) and 51 females (42%), making a gender distribution of 1.4:1. The median age distribution of the patients was 70 years, the youngest being 21 and the oldest 96 years. The most frequent cause for UGI bleeding was duodenal ulcer (n = 36; 30%) of which n = 13 were located at the bulbus back wall. Other reasons for UGI bleeding in descending order of occurrence were gastric ulcer (n = 35; 29%) of which n = 12 were located at the lesser curvature, erosive lesions of the mucosa (n = 20; 17%), esophageal varicosis (n = 12; 10%), Mallory-Weiss syndrome (n = 8; 7%), cancer (n = 5; 4%), coagulopathy (n = 4; 3%), lymphoma (n = 2; 2%), benign tumor (n = 2; 2%) and an unknown reason (n = 1; 1%). Four patients had both duodenal and gastric ulcers with each ulcer showing endoscopic evidence of bleeding, and hence each ulcer was counted as one (Table 1).

Out of the 121 patients analyzed, 17 died, resulting in a total mortality of 14%.

At admission: Of all the prognostic parameters which were considered for logistic regression, only the prognostic parameter of cirrhotic liver disease could improve the predictability of dying as a result of an UGI bleeding. Liver cirrhosis at admission increased the risk of mortality due to UGI bleeding by 4.5 fold (P = 0.005, 95%-confidence interval: 1.4-13.8). The other prognostic parameters recorded at admission (Hb, PT, age, gender and medication) did not have a predictive value (Table 2).

| Covariable | P | Statistical inclusionin model | Odds ratio | 95% confidenceinterval |

| Cirrhotic liver disease | 0.005 | Yes | 4.5 | 1.4-13.8 |

| Hb | 0.256 | No | ||

| Medication | 0.419 | No | ||

| PT | 0.672 | No | ||

| Age | 0.822 | No | ||

| Gender | 0.879 | No |

At endoscopy: Sixty-seven patients with duodenal or gastric ulcers were analyzed; fourteen prognostic parameters which were recorded during endosopic examination were tested on how far they prove to be a threat to the patients’ survival. Three of the tested parameters were taken up into the model, as their existence could help in predicting the faith of an ulcer patient. Cirrhotic liver disease (P = 0.029; 95%-confidence interval: 1.1-34.4) increased the mortality risk 5.9-fold as a result of UGI bleeding. Furthermore, male patients had a 4.8-fold higher risk of not surviving an UGI bleeding (P = 0.065; 95%-confidence interval: 1.0-34.8). An ulcer located at the bulbus back wall increased a patient’s lethality 3.5-fold (P = 0.135; 95%-confidence interval: 0.6-20.7). Other parameters, such as the Forrest classification, played no substantial role in improving the predictive strength of the statistic model (Table 3).

| Covariable | P | Statistical inclusion inmodel | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

| Cirrhotic liver disease | 0.029 | Yes | 5.9 | 1.1-34.4 |

| Gender | 0.065 | Yes | 4.8 | 1.0-34.8 |

| Duodenal ulcer (bulbus back wall) | 0.135 | Yes | 3.5 | 0.6-20.7 |

| Forrest 1 b | 0.175 | No | ||

| Forrest 2 b | 0.272 | No | ||

| Hb | 0.285 | No | ||

| PT | 0.641 | No | ||

| Medication | 0.693 | No | ||

| Forrest 3 | 0.721 | No | ||

| Forrest 1 a | 0.748 | No | ||

| Forrest 2 a | 0.782 | No | ||

| Vascular stump | 0.852 | No | ||

| Age | 0.926 | No | ||

| Gastric ulcer (small curvature) | 0.964 | No |

At the end of therapy: Only 2 of the 12 different prognostic parameters tested at the end of therapy were of significance; a patient with cirrhotic liver disease had a 5.7-fold higher risk of dying of an UGI bleeding (P = 0.005; 95% confidence interval: 1.7-19.3) as compared with a patient with healthy liver. An ulcer located at the bulbus back wall increased the lethality 3.4-fold (P = 0.092; 95%-confidence interval: 0.7-14.7). All remaining parameters did not improve the predictability and were not taken up in model (Table 4).

| Covariable | P | Statisticalinclusionin model | Odds ratio | 95 % confidenceinterval |

| Cirrhotic liver disease | 0.005 | Yes | 5.7 | 1.8-19.3 |

| Duodenal ulcer (bulbus back wall) | 0.092 | Yes | 3.4 | 0.7-14.7 |

| Bleeding recurrance | 0.271 | No | ||

| Hb | 0.341 | No | ||

| Medication | 0.345 | No | ||

| Esophageal varicosis | 0.401 | No | ||

| Number of operations | 0.42 | No | ||

| Substitution of RBCs | 0.436 | No | ||

| PT | 0.625 | No | ||

| Gastric ulcer (small curvature) | 0.799 | No | ||

| Gender | 0.809 | No | ||

| Age | 0.863 | No |

The logistic regression analysis at the 3 different time points showed that the covariable cirrhotic liver disease significantly increased the predictive value at all time points. In 21 of our evaluated patients liver disease occurred, analysis of the correlation between these patients and 9 covariables showed following findings: an initial Hb < 6 mg/dL increased the risk of dying of an UGI bleeding 9.75-folds (P = 0.077; 95%-confidence interval: 0.8-121.8). When these patients experienced recurrence bleeding during their hospital stay, the risk was increased 4.5-folds (P = 0.135, 95% confidence interval: 0.6-32.3). Moreover, additional surgical treatment resulted in a 4.5-fold risk increase (P = 0.164; 95% confidence interval: 0.5-37.4). On the contrary, the necessity to transfuse more that 6 units red blood cells (RBCs) as well as the location of a gastric ulcer at the small curvature did not increase the risk factor (Table 5).

| Covariable | Odds ratio | 95% confidenceinterval | P |

| Hb | 9.75 | 0.8-121.8 | 0.077 |

| Bleeding recurrence | 4.5 | 0.6-32.3 | 0.135 |

| Number of operations | 4.5 | 0.5-37.4 | 0.164 |

| Substitution of RBCs | 1 | 0.1-7.5 | 1 |

| Gastric ulcer (small curvature) | 1 | 0.1-13.4 | 1 |

| PT | 0.72 | 0.1-5.2 | 0.744 |

| Gender | 0.68 | 0.1-5.5 | 0.718 |

| Age | 0.3 | 0.03-3.3 | 0.322 |

| Esophageal varicosis | 0.17 | 0.02-1.8 | 0.137 |

The lethality of our evaluated patient group of 14% confirms with records of selected patient groups in other surgical departments[9]. These findings compared to the standards of today’s medicine where a lethality of more than 10% is classified as high, depict that the lethality of UGI bleeding patients has been underestimated tremendously. Although many risk factors are listed in literature and many scores[5,17] as well as indices[13,16] have been suggested, there is still ongoing uncertainty as to which parameters are threatening or which patient group is to be classified as high-risk group. The many univariate analysed records found in today’s literature do not fully make up for the multi-factorial situation of an UGI bleeding, which requires multivariate analysis. The disadvantages of prospective study designs, when it comes to long-term studies, made us choose the limited but short-termed retrospective study design.

The results of our multivariate analysis which showed that of all the possible risk factors considered at admission of a patient with UGI bleeding, only the covariable liver cirrhosis proved to be a strong enough prognostic factor in predicting the lethality of such patients. The only multivariate study, which also evaluated patients at admission[19], reported further risk factors such as age above 75 years, diagnosed carcinoma, evidence of blood in gastric aspirate and a systolic blood pressure below 90 mmHg. These findings could not be confirmed in our study. The covariable blood in gastric aspirate was considered by us as a diagnostic criterion and hence not taken into consideration.

The analysis of data gained after endoscopy showed in our study that only the evidence of cirrhotic liver disease as covariable could significantly increase the ability to predict the lethality of a patient being treated because of UGI bleeding. Other variables, such as male gender and an ulcer located at the bulbus back wall, were found to be of weaker predictable strength. On the other hand, other studies reported an evidence of disease[20,21], recurrent bleeding[2,21,22], transfusion of more than 5 units of RBCs[20,22] and an ulcer size of more than 1 cm[20,22] as significant prognostic parameters. However, the parameters including patients age above 60 years[2,22], evidence of gastric bleeding[2], an initial Hb below 100 g/L and complications[21] as prognostic parameters applicable for a patient with ulcer bleeding could not be confirmed in our multivariate analysis.

Other multivariate analyses of prognostic parameters for patients after UGI bleeding therapy found in literature confirm our result that the covariable cirrhotic liver disease is significant in predicting the lethality of patients[13,23]. Other reports which noted factors such as elevated serum transaminases[19,23], high albumin levels[23] and existence of life-threatening disease[24] tend to confirm our findings as well, as these listed factors could be interpreted as descriptive of liver disease.

The existing correlation between liver disease and the covariables; Hb, the number of operations and recurrent bleedings during treatment of UGI bleeding suggests their probable influence on the lethality of this patient group. The relationship could be due to the fact that these parameters tend to outline the risk profile of liver disease patients. A study which reports that the lethality of patients with liver disease correlates with the number of bleeding occurrences and the extent of renal failure[25], confirms our results.

In summary, most prognostic parameters used in clinical routine today are not reliable enough in predicting the patient’s vital threat due to UGI bleeding. Liver cirrhosis is the only risk factor which shows a significantly more frequent association with a fatal course after UGI bleeding in our patients.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Gilbert DA. Epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S8-13. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Katschinski B, Logan R, Davies J, Faulkner G, Pearson J, Langman M. Prognostic factors in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Morgan AG, Clamp SE. OMGE international upper gastrointestinal bleeding survey, 1978-1986. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;144:51-58. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siewert JR, Bumm R, Hölscher AH, Dittler HJ. [Upper gastrointestinal bleeding from ulcer: reduction of mortality by early elective surgical therapy of patients at risk]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1989;114:447-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. I. Study design and baseline data. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:73-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:80-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sugawa C, Steffes CP, Nakamura R, Sferra JJ, Sferra CS, Sugimura Y, Fromm D. Upper GI bleeding in an urban hospital. Etiology, recurrence, and prognosis. Ann Surg. 1990;212:521-526; discussion 526-527;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Merkle NM, Hupfauf G, Herfarth C. [Criteria in the prognosis of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. A retrospective analysis]. Med Welt. 1981;32:1431-1433. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kohler B, Riemann JF. [Acute ulcer hemorrhage. Evaluation of endoscopic therapy methods]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1994;119:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sarkar MR, Kienzle HF, Bähr R. [Can endoscopic methods decrease the mortality and complication rate of bleeding stomach and duodenal ulcer A study of the literature]. Leber Magen Darm. 1992;22:10-12, 15-18. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Morris DL, Hawker PC, Brearley S, Simms M, Dykes PW, Keighley MR. Optimal timing of operation for bleeding peptic ulcer: prospective randomised trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1277-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Börsch G, Matuk ZE, Leverkus F. [Prognosis of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Univariate and multivariate analysis of 477 episodes of hemorrhage]. Med Klin (Munich). 1987;82:774-780. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kohler B, Riemann JF. [Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1989;114:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Sandri M, Kind R, Lombardo F, Rodella L, Catalano F, de Manzoni G, Cordiano C. Risk assessment and prediction of rebleeding in bleeding gastroduodenal ulcer. Endoscopy. 2002;34:778-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalula SZ, Swingler GH, Louw JA. Clinical predictors of outcome in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. S Afr Med J. 2003;93:286-290. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Troidl H, Vestweber KH, Kusche J, Bouillon B. [Hemorrhage in peptic gastroduodenal ulcer: data as a deciding aid in the concept of surgical therapy]. Chirurg. 1986;57:372-380. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc 1990; . |

| 19. | Zimmerman J, Siguencia J, Tsvang E, Beeri R, Arnon R. Predictors of mortality in patients admitted to hospital for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Branicki FJ, Boey J, Fok PJ, Pritchett CJ, Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, Wong WS, Lam SK, Hui WM. Bleeding duodenal ulcer. A prospective evaluation of risk factors for rebleeding and death. Ann Surg. 1990;211:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chow LW, Gertsch P, Poon RT, Branicki FJ. Risk factors for rebleeding and death from peptic ulcer in the very elderly. Br J Surg. 1998;85:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Branicki FJ, Coleman SY, Fok PJ, Pritchett CJ, Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, Cheung WL, Lau PW, Tuen HH. Bleeding peptic ulcer: a prospective evaluation of risk factors for rebleeding and mortality. World J Surg. 1990;14:262-269; discussion 269-270. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Zimmerman J, Meroz Y, Arnon R, Tsvang E, Siguencia J. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with secondary upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. J Intern Med. 1995;237:331-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chojkier M, Laine L, Conn HO, Lerner E. Predictors of outcome in massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | del Olmo JA, Peña A, Serra MA, Wassel AH, Benages A, Rodrigo JM. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |