Published online Jan 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.246

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 8, 2005

Published online: January 14, 2006

AIM: To evaluate the contrast-enhanced endosonography as a method of differentiating inflammation from pancreatic carcinoma based on perfusion characteristics of microvessels.

METHODS: In 86 patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis (age: 62 ± 12 years; sex: f/m 38/48), pancreatic lesions were examined by conventional endoscopic B-mode, power Doppler ultrasound and contrast-enhanced power mode (Hitachi EUB 525, SonoVue®, 2.4 mL, Bracco) using the following criteria for malignant lesions: no detectable vascularisation using conventional power Doppler scanning, irregular appearance of arterial vessels over a short distance using SonoVue® contrast-enhanced technique and no detectable venous vessels inside the lesion. A malignant lesion was assumed if all criteria were detectable [gold standard endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine needle aspiration cytology, operation]. The criteria of chronic pancreatitis without neoplasia were defined as no detectable vascularisation before injection of SonoVue®, regular appearance of vessels over a distance of at least 20 mm after injection of SonoVue® and detection of arterial and venous vessels.

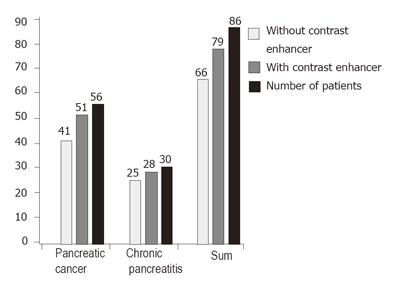

RESULTS: The sensitivity and specificity of conventional EUS were 73.2% and 83.3% respectively for pancreatic cancer. The sensitivity of contrast-enhanced EUS increased to 91.1% in 51 of 56 patients with malignant pancreatic lesion and the specificity increased to 93.3% in 28 of 30 patients with chronic inflammatory pancreatic disease.

CONCLUSION: Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound improves the differentiation between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma.

- Citation: Hocke M, Schulze E, Gottschalk P, Topalidis T, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in discrimination between focal pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(2): 246-250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i2/246.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.246

Endoscopic ultrasound is a diagnostic method with a high sensitivity for detection of small pancreatic lesions and can rule out carcinomas in almost all patients without chronic pancreatitis[1,2]. However, the differential diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, especially malignant neoplasia in patients with chronic pancreatitis is always difficult.

Differentiation between malignant and benign lesions in the liver is possible in many cases through analysis of its organ specific vascularity (portal vein/sinusoidal) using liver specific contrast media[3,4]. In contrast to the liver with its organ specific (portal vein/sinusoidal) blood supply, the pancreas does not contain pancreatic specific vasculature. Therefore, the differentiation of malignant from benign pancreatic lesions seems to remain an unsolved problem today though technology is improved. The same problem arises using computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[5-7]. In patients with chronic pancreatitis the specificity of differentiation between malignant and benign lesions in the pancreas is reported to be as low as 33%-75%[8,9].

However, the introduction of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration has made this easier[10-12]. The gold standard is still surgery in combination with pathological examination of histological specimens. Nevertheless an improved non-invasive method of detecting malignant tissue is preferable. In the present study, contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound was used to differentiate between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions.

A total of 120 patients (age: 61 ± 18 years; sex: f/m 56/64) who showed undifferentiated pancreatic lesions in ultrasound and computed tomography were included into the present study. Reference imaging examinations (e.g. computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography [PET]) were performed as part of the clinical work-up of the patients. Patients with mucinous cyst adenoma (n = 1), serous cyst adenoma (n = 5), serous cyst adenocarcinoma (n = 4) and neuroendocrine tumours (n = 6) were excluded from the study. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound was not performed in seven patients due to severe heart failure NYHA III/IV, a contraindication for SonoVue®. The image quality was inadequate in one patient due to severe pancreatic lipomatosis. Furthermore, the lesion could not reached in 10 patients by the biopsy needle. Finally, 86 patients (age: 62 ± 12 y e a r s; sex: f/m 38/48) were included in the study.

Informed consent according to the ethical guidelines from Helsinki was obtained from all patients after the patients were informed of the purpose of the study before ultrasound examination was started.

Endoscopic ultrasound was performed using an electronic linear ultrasound probe (Pentax FG 38 UX; Hitachi EUB 525). The pancreas was examined as previously described[13]. As contrast enhancing agent, Sonovue® (Bracco, Milano, Italy) was applied in all patients. During the procedure all patients were monitored as previously described[14,15].

The imaging criteria of chronic pancreatitis have been recently discussed[16,17]. All patients received transabdominal examination as previously described[18]. In this study the specificity and sensitivity of endoscopic ultrasound were tested before and after injection of the contrast- enhancing agent SonoVue® in differentiating focal chronic pancreatitis from pancreatic carcinoma. Tumour location, morphology, echogenicity and size were documented. If a lesion was detected, vascularity and possible vessel infiltration were evaluated using conventional endoscopic power Doppler ultrasonography in comparison to the surrounding pancreatic tissues and regarded as hyper-, iso- or hypovascular.

The pulse repetition frequency and wall filters were individually adjusted to enable the detection of parenchymal and intratumoral vessels and to avoid artefacts such as “blooming”. To detect vascular complications such as portal vein thrombosis, the portal vein was also investigated in variable scans. If any echogenic material was found in the lumen of the portal vein, power Doppler was used to detect flow inside the material. If flow was detected, pulsed wave Doppler analysis was performed to differentiate between pulsatile arterial and non-pulsatile (portal-) venous perfusion. In addition, the following criteria for malignant lesions were used: irregular lesion without clear structure, stenosis of pancreatic duct with prestenotic duct dilatation and infiltration of vessels or surrounding organs.

In a prestudy, Levovist and SonoVue® were compared in 10 consecutive patients, which demonstrated best results in imaging pancreatic perfusion using SonoVue (2.4 mL). Therefore, contrast-enhanced ultrasound was applied using SonoVue® 2.4 mL (BR1, Bracco, Italy) to evaluate if this contrast application could improve the characterisation of tumour vascularity. SonoVue® (2.4 mL) was injected following a flash of 10mL saline solution via a catheter (1.2 mm in diameter or larger) into a cubital vein. Hitachi EUB 525 was used. Continuous scanning was performed with its pulse repetition frequency set at 7 kHz to gain optimal signals as low as possible but to avoid artefacts with an adjusted wall filter. In contrast to the technique described by Becker et al [13], we combined the analysis of the detected vessels with pulse wave (pw) Doppler analysis. The sonograms were stored on videotapes and re-evaluated blind to the clinical settings using a semiquantitative scoring system to evaluate the vascularity during different phases of perfusion.

Criteria of chronic pancreatitis without neoplasia were defined as no detectable vascularisation or regular appearance of vessels over a distance of at least 20 mm before and after injection of SonoVue® and detection of arterial and venous vessels in the contrast-enhanced phase.

Criteria for malignancy were no detectable vascularisation before injection of SonoVue®, irregular appearance of arterial vessels over a short distance after injection of SonoVue® and no detection of venous vessels in the lesion. A malignant lesion was assumed if all criteria were detectable.

The whole procedures were stored on videotapes. The criteria of benign and malignant pancreatic tumour using contrast-enhanced power Doppler are summarized in (Table 1)

| Kind of lesion | Vessel architecture using conventional power mode | Arterial or venous in the lesion using continuous duplex scanning | Vessel architecture using contrastenhanced power mode |

| Pancreatic cancer | No visible vascularisation | Only arterial vessels | Irregular, chaotic vessels |

| Focal pancreatitis | Nearly no visible vascularisation | Both arterial and venous vessels in the lesion | Regular with no changing diameter |

EUS-guided fine needle aspiration was performed in all patients. The patients with benign diseases were followed up for at least 12 mo. After detection of the lesion by endoscopic ultrasound, the diagnostic criteria of endoscopic ultrasound were used to get a primary diagnosis. Then the lesion was investigated with the help of power Doppler mode before and after the application of 2.4 mL SonoVue® for over 3 min and the secondary diagnosis was established. At the end of the procedure all lesions were punctured with a 22 G fine needle aspiration system (Cook Deutschland GmbH, Mönchengladbach, Deutschland) to confirm the diagnosis using cytology. For optimization of the cytology results more then 6 needle passes of the lesion were used as previously described[10,19]. The material was spread out on to a normal microscopic glass platelet and dried by air. Then, a blood stain (May-Gruenwald/Giemsa) was made. In case of remaining tissue, the tissue biopsy was fixed in formalin for histological examination. A malignant process was assumed if the result of cytological examination was Papanicolaou IV or V or the histological examination was positive for malignant tissue. A benign process was assumed if the result of cytological examination was Papanicolaou I or II.

After detection of the lesion by endoscopic ultrasound and the use of contrast-enhanced Doppler sonography, the final diagnosis was achieved by endoscopy-guided puncture. The material was immediately evaluated and re-puncture was performed if the material was not representative. Re-puncture was successful in 17 patients. Surgery was performed in 19 patients leading to concordant results. There was an inoperable tumour in the following diagnostic procedures (for example metastasis of lung, condition of the patient etc.) or no other sign of pancreatic cancer in all other patients. If the operation was refused, we re-examined the patients with assumed chronic pancreatitis 6 and 12 mo after the diagnosis. In case of no signs of malignant tumour 12 mo after the initial diagnosis, pancreatic cancer was ruled out.

Final diagnosis was obtained by endoscopy-guided puncture in all 86 patients. Furthermore the diagnosis was confirmed by surgery in 19 patients and by re-examination after 6 and 12 mo in all other patients with suspect chronic pancreatitis.

Adequate visualisation of the pancreas and the suspected lesion could be achieved in all patients. The diagnosis was confirmed by conventional B-mode and power Doppler endoscopic ultrasound in 41 of 56 patients using more then 2 of the previously described 3 B-mode ultrasound criteria for malignant lesions. The sensitivity was 73.2%. The diagnosis was confirmed in absence of the mentioned criteria in 25 of 30 patients with focal chronic pancreatitis. The specificity was 83.3%. However, these results were comparable to other reports[8]. The findings are shown in (Table 2).

| Pancreatic carcinoma | Chronicpancreatitis | ||

| Good quality of imaging | 56 | 30 | |

| Localization | Head | 35 | 25 |

| Corpus | 12 | 4 | |

| Tail | 9 | 1 | |

| Size (cm –SD) | 3.8 (1.09) | 3.02 (0.94) | |

| Echogeneicity | Hypoechoic | 41 | 3 |

| Mixed echoic | 15 | 27 | |

| Borders | Clear | 15 | 25 |

| Irregular | 41 | 5 | |

| Structure | Irregular | 41 | 5 |

| Regular | 15 | 25 | |

| Ducts | Dilated | 39 | 6 |

| Not dilated | 17 | 24 | |

| Lymphnodes | Visible | 15 | 4 |

| Not present | 41 | 26 | |

| Invasion | Visible | 23 | 0 |

| Not visible | 33 | 30 |

The main criteria for malignant lesions were the complete absence of venous vessels by using power Doppler in combination with pw-Doppler examination of the lesion within 3 min after contrast enhancer application. The quality of imaging was acceptable if the time was long enough to scan all visible vessels by pw-Doppler. In this study, application of the contrast enhancer SonoVue had to be repeated in 4 patients to achieve adequate image quality. In addition, using the criteria of Becker et al [13], hypervascularity was observed in the area of interest in 26 patients and hypovascularity in 4 patients with chronic pancreatitis (specificity 86.6%). Hypervascularity was observed in 10 patients and hypoperfusion in 46 patients pancreatic carcinoma (sensitivity 82.1%).

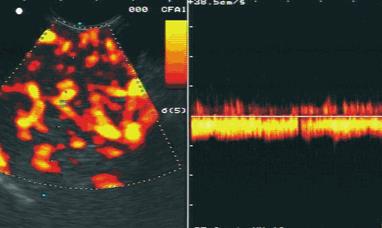

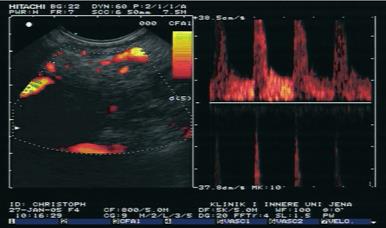

The diagnosis was confirmed in 51 of 56 patients with pancreatic carcinoma using the main criteria of malignant vascularisation with a sensitivity of 91.1%. The diagnosis was confirmed in 28 of 30 patients with focal chronic pancreatitis using the criteria of benign vascularisation with a specificity of 93.3%. The results are shown in Figure 1. Typical endoscopic ultrasound images after injection of contrast enhancer SonoVue® in power Doppler mode are demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3.

Contrast-enhanced techniques provide information on vascularity and blood flow in normal and pathological tissues. The use of 2nd generation contrast agents in combination with low mechanical index techniques can improve the transabdominal application of contrast-enhanced techniques allowing real-time imaging with or without three dimensional reconstruction. In contrast to the frequently applied transabdominal technique[20,21] there are only a few reports on contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound[13,22-24]. Endoscopic ultrasound has been widely used in the past 20 years while real time contrast using low mechanical index (MI) is still restricted to the transabdominal application. In the present study, we showed that contrast-enhanced power Doppler ultrasonography in combination with power Doppler analysis could improve the differentiation between malignancy and chronic panreatitis.

The pressure inside ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is higher due to surrounding fibrous tissues, which could explain the observed phenomenon that only arterial signals can be displayed in patients with malignancy with contrast-enhanced Doppler techniques, whereas both arterial and venous signals can be displayed in patients with chronic pancreatitis.

We rarely observed detectable vascularity and irregular vessel architecture in almost all patients with pancreatic carcinoma after application of the contrast-enhancing agent SonoVue®. However, both venous and arterial vessels were detectable in benign lesions. In contrast, only arterial vessels were observed in malignant lesions. The sensitivity in the discrimination between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions increased from 73.2% by endoscopic ultrasound to 91.1% using contrast-enhanced power Doppler ultrasound combination with power Doppler endoscopic ultrasound. In addition, the specificity increased from 83.3% to 93.3%. The analysis of contrast enhancing vessels in the pancreatic masses by power Doppler ultrasound in combination with power-Doppler endoscopic ultrasound is superior to the analysis of the intensity of vascularisation by power Doppler ultrasound only as demonstrated by Becker et al [13].

The different vessel structures in malignant tissue are in accordance with a recently published study analysing the architecture of vessels in pancreatic carcinoma in rats[25]. However, Weskott et al [26] reported that venous vessels are rarely found in malignant lymph nodes.

Bhutani et al[9] have observed an effect of Levovist® imaging on abdominal vessels in pigs. In 1998, Hirooka et al [22] demonstrated that lesions in gallbladder and pancreas can be visualized using the contrast enhancer Albunex® , focal pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma can be differentiated by analysing the contrast enhancement. They also reported that patients with focal chronic pancreatitis reveal enhancement whereas patients with pancreatic carcinoma have no enhancement[23].

Recently, Nomura et al [24] showed that improved staging of oesophageal and gastric cancer after application of an ultrasound contrast enhancer leads to better visualisation of the gut layers. Up to now there is only one study using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound with a 2nd generation contrast agent[13]. Rickes et al [27] have reported a similar finding.

In addition to their observations, we observed contrast enhancement of the 2nd generation contrast agent SonoVue® in both benign and malignant pancreatic lesions. To confirm our results we used endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration of the lesions. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration has become a highly valuable technique for acquisition of cytologic specimens in pancreatic diseases in the last 10 years. False-positive EUS-FNA cytologies do occur but seldom[28] in large series of EUS-FNA for pancreatic masses. EUS-FNA provides a cytologic diagnosis of 80%-94% malignancies[29-32].

In our study, the successful rate was 90% (successful fine needle aspiration of pancreatic masses in 86 of 96 patients), which is in accordance with the literature. The 22 G fine needle aspiration system allowed histological examination of the specimens in 8% of the cases. Up to now no patient with chronic pancreatitis developed pancreatic cancer during the 12-mo follow-up. The cytological results could be confirmed in all the 19 patients undergone surgery.

The method is limited by hindered passage through the pylorus and depth of penetration. As all the new methods are concerned, a certain training factor has to be taken into account since a steady and targeted transducer manipulation is the prerequisite for optimal image documentation. Sometimes, severe lipomatosis of pancreas reduces image quality. It must be mentioned that the best results can be achieved using the present method. For equal results in modern sonographic systems, changes in the pre-settings of colour Doppler are required.

To date, ultrasonography is the most commonly used imaging modality in many countries. The advantages of endoscopic ultrasound (e.g. lack of radiation exposure, relatively low cost) are countered by its operator-dependency. Endoscopic ultrasound using contrast- enhancing agents may improve our understanding of the morphologic imaging methods through additional analyses of the functional criteria like perfusion with better characterization of tumours, lymph node staging and organ infiltration. The improved image (video) documentation enhances confidence in the method.

In conclusion, contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound improves the differentiation between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma and seems to be a useful method in clinical practice.

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor cao L

| 1. | Levy MJ, Wiersema MJ. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2002;16:29-38, 43; discussion 44, 47-9, 53-6. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Ito K. Endoscopic approach to early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2004;28:279-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dietrich CF, Ignee A, Trojan J, Fellbaum C, Schuessler G. Improved characterisation of histologically proven liver tumours by contrast enhanced ultrasonography during the portal venous and specific late phase of SHU 508A. Gut. 2004;53:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | von Herbay A, Vogt C, Häussinger D. Pulse inversion sonography in the early phase of the sonographic contrast agent Levovist: differentiation between benign and malignant focal liver lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1191-1200. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Taylor B. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas versus chronic pancreatitis: diagnostic dilemma with significant consequences. World J Surg. 2003;27:1249-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boll DT, Merkle EM. Differentiating a chronic hyperplastic mass from pancreatic cancer: a challenge remaining in multidetector CT of the pancreas. Eur Radiol. 2003;13 Suppl 5:M42-M49. [PubMed] |

| 7. | De Backer AI, Mortelé KJ, Ros RR, Vanbeckevoort D, Vanschoubroeck I, De Keulenaer B. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnostic role of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:304-310. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wiersema MJ. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound in diagnosing and staging pancreatic carcinoma. Pancreatology. 2001;1:625-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bhutani MS, Gress FG, Giovannini M, Erickson RA, Catalano MF, Chak A, Deprez PH, Faigel DO, Nguyen CC. The No Endosonographic Detection of Tumor (NEST) Study: a case series of pancreatic cancers missed on endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Südhoff T, Hollerbach S, Wilhelms I, Willert J, Reiser M, Topalidis T, Schmiegel W, Graeven U. [Clinical utility of EUS-FNA in upper gastrointestinal and mediastinal disease]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:2227-2232. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Brand L, Knöfel WT, Bobrowski C, Topalidis T, Thonke F, de Werth A, Soehendra N. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for focal pancreatic lesions in patients with normal parenchyma and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2768-2775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gress F, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:459-464. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Becker D, Strobel D, Bernatik T, Hahn EG. Echo-enhanced color- and power-Doppler EUS for the discrimination between focal pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Seifert H, Schmitt TH, Gültekin T, Caspary WF, Wehrmann T. Sedation with propofol plus midazolam versus propofol alone for interventional endoscopic procedures: a prospective, randomized study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1207-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wehrmann T, Kokabpick S, Lembcke B, Caspary WF, Seifert H. Efficacy and safety of intravenous propofol sedation during routine ERCP: a prospective, controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:677-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jenssen C, Dietrich CF. [Endoscopic ultrasound in chronic pancreatitis]. Z Gastroenterol. 2005;43:737-749. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Raimondo M, Wallace MB. Diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis by endoscopic ultrasound. Are we there yet. JOP. 2004;5:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Dietrich CF, Chichakli M, Hirche TO, Bargon J, Leitzmann P, Wagner TO, Lembcke B. Sonographic findings of the hepatobiliary-pancreatic system in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:409-16; quiz 417. [PubMed] |

| 19. | LeBlanc JK, Ciaccia D, Al-Assi MT, McGrath K, Imperiale T, Tao LC, Vallery S, DeWitt J, Sherman S, Collins E. Optimal number of EUS-guided fine needle passes needed to obtain a correct diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harvey CJ, Blomley MJ, Eckersley RJ, Heckemann RA, Butler-Barnes J, Cosgrove DO. Pulse-inversion mode imaging of liver specific microbubbles: improved detection of subcentimetre metastases. Lancet. 2000;355:807-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dietrich CF, Schuessler G, Trojan J, Fellbaum C, Ignee A. Differentiation of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:704-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hirooka Y, Goto H, Ito A, Hayakawa S, Watanabe Y, Ishiguro Y, Kojima S, Hayakawa T, Naitoh Y. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in pancreatic diseases: a preliminary study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:632-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hirooka Y, Naitoh Y, Goto H, Ito A, Hayakawa S, Watanabe Y, Ishiguro Y, Kojima S, Hashimoto S, Hayakawa T. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in gallbladder diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nomura N, Goto H, Niwa Y, Arisawa T, Hirooka Y, Hayakawa T. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced EUS in the diagnosis of upper GI tract diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schmidt J, Ryschich E, Daniel V, Herzog L, Werner J, Herfarth C, Longnecker DS, Gebhard MM, Klar E. Vascular structure and microcirculation of experimental pancreatic carcinoma in rats. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:328-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Weskott HP; Möglichkeiten der Lymphknotendiagnostik, Tagungsband, 28. Dreiländertreffen DEGUM, SGUM, ÖGUM, 6.-9. October 2004, Hannover. . |

| 27. | Rickes S, Unkrodt K, Neye H, Ocran KW, Wermke W. Differentiation of pancreatic tumours by conventional ultrasound, unenhanced and echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1313-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schwartz DA, Unni KK, Levy MJ, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ. The rate of false-positive results with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:868-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Binmoeller KF, Rathod VD. Difficult pancreatic mass FNA: tips for success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S86-S91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chang KJ, Nguyen P, Erickson RA, Durbin TE, Katz KD. The clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1386-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Giovannini M, Seitz JF, Monges G, Perrier H, Rabbia I. Fine-needle aspiration cytology guided by endoscopic ultrasonography: results in 141 patients. Endoscopy. 1995;27:171-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |