INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy is an established procedure for investigating patients with diseases of the colon and terminal ileum, including patients with prior colonic adenomas or cancer, fecal occult blood loss, a family history of cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, evaluation of iron deficiency anemia and patients with hematochezia[1]. However, although it is expected that endoscopists should be able to intubate the cecum in 90% of attempts[2], in practice this is followed less often than not[3]. On several occasions even a complete colonoscopic examination may not be possible or may not show any abnormality in patients with hematochezia. Moreover, during active bleeding subtle changes in the colon may not be appreciated and sometimes even gross lesions may be missed. Due to this argument and the fact that most of the bleeding will stop by itself, some workers advise that colonoscopy should be performed only after cessation of active bleeding and after proper colonic preparation[4].On the contrary, others prefer to perform colonoscopy as an emergent procedure, so that more lesions are detected early enough for endoscopic therapy to be applied[5,6].

Terminal ileoscopy is an integral part of complete colonoscopy. Retrograde terminal ileoscopy has been noted to be useful in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, diarrhea, lymphoma, cytomegalovirus-induced ileitis, tuberculosis, portal hypertension and a host of other conditions involving the terminal ileum[7-21]. In a recent study, we have noted that obtaining blind biopsies from even a normal-appearing terminal ileum is useful in patients suspected to have ileocaecal tuberculosis[22]. However, despite being recommended by several authors[7-19,22], terminal ileoscopy is not routinely performed when colonoscopy is done in all patients undergoing colonoscopy [3]. A more recent study has noted that routine ileoscopy is very useful and easy to perform after proper training has been imparted. However, although stray reports have noted abnormalities in the terminal ileum in hematochezia patients with normal colonoscopy, we are not aware of any study that has dealt with this problem in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between January 1997 and March 2005, colonoscopy with retrograde ileoscopy was attempted in all patients with hematochezia in whom colonoscopy till the cecum was reported to be normal either during emergency colonoscopy or a routine colonoscopy performed immediately after cessation of bleeding. Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy was also performed in these patients but did not reveal any abnormality. Two of these patients had another episode of hematochezia in the past (8 mo and 13 mo before the present hospitalization) and received 4 and 6 units of whole blood transfusion respectively. UGI endoscopy and colonoscopy performed elsewhere did not reveal any abnormality.

Methods

Repeat colonoscopy was performed in our unit. Colonic preparation was performed with either one liter 10% (100 g/L) mannitol solution followed by a WHO oral rehydration solution or a polyethylene glycol-electrolyte-based solution (Peglec, Tablets India, Ltd., Chennai, India). On repeat colonoscopy, a careful search was made for any lesion in the colon. After reaching the cecum, attempt was made to localize the ileocaecal opening and intubate the terminal ileum. Once in the terminal ileum all attempts were made to go as far as possible in the ileum. Any abnormality in the mucosa of the terminal ileum was carefully recorded and biopsies were obtained from suspicious-looking lesions. Biopsies were not obtained from lesions that were likely to be of vascular origin such as ileal varices, spiders, angiomatous malformations and Dieulafoy’s lesions.

RESULTS

During the study period there were 39 patients admitted for hematochezia in whom colonoscopy till cecum did not reveal any abnormality. There were 36 males and 3 females. The mean (SD) age of these patients was 44.7 (10.6) years. Of these patients, 34 were admitted to our hospital for hematochezia and the other five were referred from other centers after no lesion could be detected on colonoscopy in these patients. Of the 34 patients admitted to our center, colonoscopy was performed as an emergency procedure in 23 and 11 patients after cessation of the bleeding and bowel preparation. All colonoscopies and ileoscopies were performed by the two senior authors of the paper.

Full-length colonoscopy till the cecum could be performed in all the patients. Colonoscopy did not reveal any abnormality in 38 patients. However, in one of the patients superficial ulcers were seen in the cecum. Despite all efforts, the terminal ileum could not be intubated in three patients. One of the patients had a history of hematochezia 8 months before the present hospitalization.

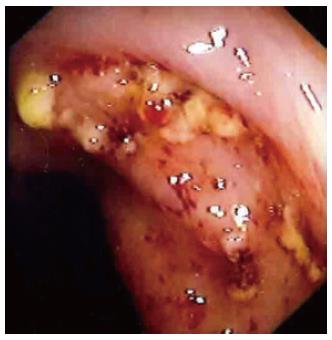

Of the 36 patients in whom the terminal ileum could be visualized, no abnormality was noted in 31 patients. The other five patients had endoscopic findings on terminal ileoscopy. Nodularity and ulceration of the ileal mucosa were noted in one patient (Figure 1). This patient had superficial ulcers in the cecum too. A Dieulafoy’s lesion was noted in one patient (Figure 2). This patient had massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding 13 months prior to the present hospitalization. An UGI endoscopy and colonoscopy at that time did not reveal any abnormality and the patient recovered after conservative management. Another patient had an angiomatous malformation (Figure 3). Ulcers were noted in the terminal ileum in two patients. One of these patients had typhoid fever (Figure 4). In the other patient ulcers were noted only on the ileal side of the ileocecal valve (Figure 5).

Figure 1 Retrograde ter-minal ileoscopy showing nodularity and ulceration in the ileal mucosa.

Figure 2 Dieulafoy’s lesion of the terminal ileum.

Figure 3 Angiomatous mal-formation seen at ileoscopy.

Figure 4 Ileal ulcers seen at retrograde ileoscopy.

Figure 5 Non-specific ulcers in the terminal ileum.

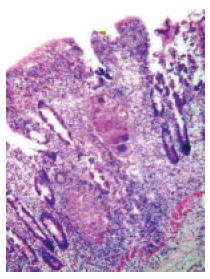

Biopsies obtained from the superficial ulcers in the cecum showed non-specific inflammatory changes. Histological examination of the biopsies obtained from the nodularity and ulcers in the ileum of this patient revealed non-caseating granulomas consisting of Langhans’ giant cells and epithelioid cells with a surrounding cuff of lymphocytes (Figure 6), suggestive of tuberculosis. The two other patients with ulcers showed evidence of non-specific inflammation. The patient with typhoid fever was diagnosed to have typhoid ulcer and the other patient to have non-specific ulcer.

Figure 6 Histological examination of the biopsies obtained from the area of nodularity and ulceration in the terminal ileum showing noncaseating granulomas consisting of Langhans’ giant cells and epithelioid cells.

Note that a cuff of lymphocytes surrounds the granuloma (HE ×80).

DISCUSSION

Colonoscopy remains the procedure of choice for most diseases of the large bowel, including patients with hematochezia[1]. However, the timing of colonoscopy in patients with hematochezia is debatable. While some workers feel that an emergency colonoscopy should be performed in such patients due to the fact that it can detect evanescent findings such as stigmata of recent bleeding or reversible ischemia and can lead to a rapid diagnosis of the cause culminating in its endoscopic management[5,6], the detractors of urgent colonoscopic examination feel that urgent colonoscopy decreases sensitivity in the presence of active bleeding and that in most cases there is spontaneous cessation of bleeding, even without rendering endoscopic therapy[4]. Others prefer to perform a bleeding scan and angiography in such patients. The advantages of this procedure include the ability to identify the bleeding site whether in the small or in the large bowel, the lack of preparation required for colonoscopy and the ability to perform therapeutic interventions[23]. No matter what the choice of the investigation, an UGI endoscopy must be performed in all such patients, since in about 10% of such patients an UGI source may be responsible for the hematochezia[24]. Although colonoscopy is performed routinely for suspected abnormalities in the colon[1], ileoscopy is not commonly employed in the work-up of patients with ileocolonic abnormalities[3]. This is despite the fact that a number of studies have demonstrated the utility of retrograde ileoscopy during colonoscopic examination of the large bowel[7-22]. A recent study speculated that perceived difficulty of ileal intubation, time constraints, and the expectation of a low diagnostic yield are the likely reasons for the resistance on the part of the endoscopists in attempting retrograde ileoscopy[3].

The results of this study show that a carefully performed colonoscopy that includes retrograde terminal ileoscopy is a very useful tool to diagnose the cause of hematochezia in patients in whom an earlier colonoscopic examination has not revealed any abnormality. Although the yield appeared to be low (13%), the lesions encountered were important in the sense that the diagnosis could be achieved, helping in the treatment of these lesions. In another study, the yield of ileoscopy, performed with an enteroscope in patients with unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, was noted to be even lower than that noted in the present study. However, in that study the ileal intubation could be achieved in only 39% of patients[25], which is far less than that achieved in most other studies[10,16,20-22]. The probable reason for the low ileal intubation rate is the fact that the authors used a more flexible enteroscope instead of a conventional colonoscope for ileoscopy. Moreover, only 10 patients with unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding were enrolled in that study as opposed to those with hematochezia in the present study. It is not clear whether or not these patients had lower gastrointestinal bleeding severe enough to cause hematochezia. The chances of finding a lesion in the terminal ileum was considerably more in our group of patients due to the fact that they had lower gastrointestinal bleeding severe enough to cause hematochezia.

Two of the patients in this series had what is called as obscure GI bleeding[26]. They had an episode of hematochezia in the past and UGI endoscopy as well as colonoscopy did not reveal any abnormality. Unfortunately in one of these patients, despite all attempts, the terminal ileum could not be intubated. However, in the other patient a Dieulafoy’s lesion was detected. If ileoscopy was performed with the lesion detected and treated during the previous colonoscopy, the patient would have been spared of a potentially life-threatening episode of hematochezia, suggesting that colonoscopy and ileoscopy should be performed in patients with obscure GI bleeding [26]. We would go a step further and suggest that ileoscopy should be performed while a colonoscopy is performed for all GI bleeding. Waiting for a second episode of bleeding (that might be massive) so as to be labeled as obscure GI bleeding is not warranted. In fact ileoscopy should be an integral part of colonoscopy and all attempts should be made to intubate the terminal ileum during colonoscopy performed for any indication.

Ileoscopy was noted to be useful in one of our patients in diagnosing the cause of the ulcer. In this patient an earlier colonoscopic examination missed superficial ulcers in the cecum. However, histological examination of biopsies obtained from the ulcers in the cecum showed non-specific changes. If ileoscopy was not performed and biopsies were not obtained from the ileal ulcers, the diagnosis of a curable disease would not have been possible. We have earlier observed such differences in the histological appearance of biopsies obtained from different areas of the colon in patients with colonic tuberculosis[27]. Patients with isolated tuberculous involvement of the terminal ileum have been reported[18].

Except for one patient in whom superficial cecal ulcers were missed on colonoscopy, all the other patients had their disease localized to the terminal ileum. This was because of the design of the study, since patients with lesions found at the first colonoscopy (emergency or elective) were not enrolled. However, in an earlier study, ileoscopy revealed the findings or the diagnosis in 8 of the 57 cases where it was possible and colonoscopic as well as radiological examinations were normal. This group included two patients with lower GI bleeding in whom colonoscopy was normal and ileoscopy revealed typhoid ulcers and NSAID-induced ulcers respectively[16].

The findings noted in this study may not be totally valid in the West, since endoscopists in the developed countries are unlikely to encounter a patient with hematochezia due to typhoid ulcers or tuberculosis. However, with tuberculosis raising its head once again in the developed countries[28-30], such a scenario cannot be totally discounted. The other lesions noted in the present series such as Dieulafoy’s lesion, non-specific ulcers and angiomatous malformations are universal diseases and may be seen more commonly.