Published online May 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2730

Revised: February 8, 2006

Accepted: February 18, 2006

Published online: May 7, 2006

The treatment of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is still far from optimal, particularly for those subpopulations that do not respond to the standard combination therapy with Interferon-α (IFNα) plus ribavirin. Although in some cases the use of higher doses or longer treatment periods may be effective, these approaches are generally associated with a higher incidence of adverse events, which may either lead to a reduction in patient compliance or require drug withdrawal. IFNβ could represent an interesting alternative for treating CHC patients. Controversial data about IFNβ efficacy in CHC exist, the main reason being that many results stem from pilot studies with small cohorts of patients. However, promising results have been obtained in some subgroups of patients that fail to respond to IFNα. Additionally, the good tolerability of IFNβ represents an important advantage of the drug. The rates of dropouts in controlled clinical trials, as well as the need for dose reductions or treatment discontinuation are very low. It might be worth assessing the value of IFNβ plus ribavirin in randomized studies with a larger cohort of patients, not eligible or not tolerating standard therapy, and for non-responders.

- Citation: Moreno-Otero R, Trapero-Marugán M, Gómez-Domínguez E, García-Buey L, Moreno-Monteagudo J. Is interferon-beta an alternative treatment for chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(17): 2730-2736

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i17/2730.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2730

In the absence of antiviral treatment, chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a liver disease characterized by the development of necroinflammatory changes and progressive liver fibrosis leading to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. CHC represents a significant public health problem[1,2]. The objective of treatment is to eradicate infection and prevent progression to cirrhosis and associated complications of end-stage liver disease. According to the latest NIH Consensus Development Statement for the management of CHC, all patients with CHC are potential candidates for antiviral therapy[2]. The therapeutic strategy to be followed is currently well defined, mainly due to the significant progress that has occurred since the initial availability of Interferon-α (IFNα). The approval of ribavirin in combination therapy regimens with IFNα has dramatically improved therapy. Another advance was the introduction of pegylated IFNα, which allows a once-weekly subcutaneous administration and shows more favourable pharmacokinetics and greater efficacy. The highest sustained virological response (SVR) rates are attained with pegylated IFNα in combination with ribavirin[3]. Large randomised trials have shown efficacy of this combination in approximately half of the patients[4,5]. In spite of these advances, a number of patients do not respond to treatment with IFNα, or discontinue treatment due to the occurrence of adverse events associated with therapy.

IFNβ represents a potential therapeutic alternative for treatment of chronic viral hepatitis. In fact, in some countries, mainly in Japan, IFNβ already plays a role in therapeutic protocols. IFNβ belongs to the same family of glycoproteins as IFNα. Although both cytokines present different physicochemical and biological properties in many respects, IFNβ shares with IFNα some of the pharmacological characteristics thus indicated for treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection[6,7].

Three different types of IFNβ are available[8]: (1) Natural human IFNβ (nIFNβ) is produced by human fibroblasts, and is currently used in Japan for treating CHC; (2) Recombinant human IFNβ-1a (rhIFNβ-1a) is produced by mammalian cells and is identical to the IFNβ that occurs naturally in humans; (3) Recombinant human IFNβ-1b (IFNβ-1b) is produced by E-coli and has its cysteine at position 17 substituted by serine. RhIFNβ-1a has been reported to be less immunogenic and more potent than the other forms of IFNβ[9]. IFNβ can be administered intravenously (iv), intramuscularly (im) or subcutaneously (sc). Pharmacokinectic and pharmacodynamic studies[10] have shown that the extent and duration of the clinical and biologic effects of IFNβ are independent of the route of administration.

In this article we review the data currently available on the efficacy and safety of IFNβ for the treatment of CHC. A number of clinical trials have been conducted worldwide. However, many of them are pilot studies with small cohorts of patients targeting different subpopulations, thus frequently leading to controversial results. As a result, one has to be cautious when extracting conclusions. Distinct factors have been reported to influence efficacy of IFNβ in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, including the dose, frequency of administration, the dynamics of HCV clearance in the initial phases of treatment, patient age, pre-treatment viral load, HCV genotype and route of administration.

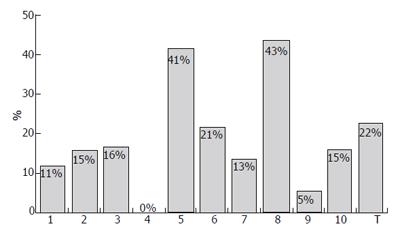

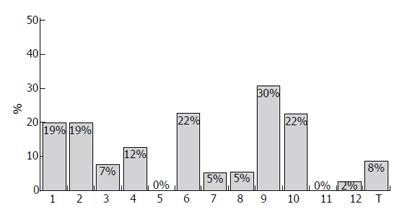

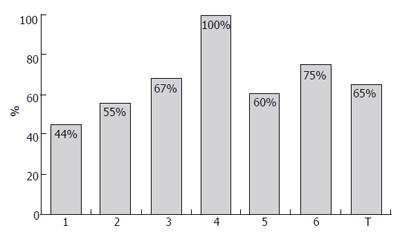

Several studies have been conducted to investigate the most appropriate doses and regimens of IFNβ for CHC showing, in general, that the highest doses did not have the greatest efficacy and result in poorer tolerability[11-14]. Generally, the intravenous administration achieved better SVR rates than subcutaneous route (Figures 1 and 2); furthermore, intravenous IFNβ obtains better results than recombinant IFNα monotherapy in CHC patients with genotype 1[12,15-36]. Similarly to other therapies with recombinant IFNα, patients infected with HCV genotype no-1 obtain higher SVR rates (Figures 1 and 3)[17,18,21-23,37]. In a randomized study with 92 CHC patients, a better biochemical response was observed in CHC patients treated with 6 million units (MIU) nIFNβ three times a week for 12 mo than in those administered 3 MIU (21% vs 4.5%, respectively)[12]. The frequency of administration also seems to play a role in the effects of IFNβ. Shiratori et al treated 22 CHC patients with high viral load and HCV subtype 1b with two different regimens of IFNβ: 6 MIU once a day, or 3 MIU twice a day[13]. The efficacy of the drug was higher with twice daily administration: negativity for HCV-RNA occurred in 18%, 73% and 89% of patients at 1, 2 and 3 wk, respectively, in the twice-a-day group, in contrast to 0%, 0% and 18% in the once-a-day group. However, the incidences of (a) reduced platelet counts and albumin levels; (b) increased serum ALT/AST; and (c) renal toxicity, were higher for the twice-a-day group. A similar outcome in terms of efficacy and safety was observed by Fujiwara et al in a randomized trial with 54 patients, treated either with 6 MIU every 24 or with 3 MIU every 12[14]: serum HCV-RNA disappeared in 95% of the patients on the twice-daily regimen, as compared with 74% in the once-daily injection group. Tolerability to IFNβ (in terms of proteinuria, thrombocytopenia and serum ALT levels elevation) was worse in patients receiving 3 MIU every 12 h. At the same time, in an other study, no differences between twice-daily and once-daily administrations were observed: Suzuki et al randomized 20 CHC patients with genotype 1b and high HCV-RNA level to receive either twice-daily 3 MIU IFNβ (group A) or once-daily 6 MIU IFNβ for 4 wk (group B)[24]. All patients then received a daily dose of 6 MIU IFNβ for 12 wk, followed by IFNα three times weekly for 16 wk; the treatment of group A was not superior to that of group B in terms of sustained responses, while adverse effects were more frequent and pronounced in group A.

The mechanisms underlying the possible enhanced antiviral efficiency of frequent dosing of IFNβ were investigated in another study: serum HCV dynamics and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) and MxA mRNA levels were monitored in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of 140 CHC patients randomized to receive twice daily 3 MIU IFNβ or once daily 6 MIU/d IFNβ[38]. The twice-a-day administration reduced the expression level of peak PKR and MxA gene expression in the first phase (4 h after single administration), although it was higher in the second phase. Furthermore, this regimen induced greater rates of HCV decline in the second phase. This enhanced clearance of HCV- infected cells probably represents the basis for the improved efficacy of frequent administration of IFNβ.

Fukutomi et al also studied the relation of HCV clearance during the initial phases of treatment with IFNβ with efficacy of treatment[39]. They showed that the decay slope calculated from HCV-RNA levels determined at 0 and 24 after the initiation of IFNβ treatment of CHC patients correlated with the proportion of sustained responders. Based on these findings, the authors proposed that the decay slope of viral clearance could be used as a predictor of the efficacy of therapy. However, further mechanistic data may be needed to confirm this possibility. Additional factors influencing sustained response to IFNβ have been identified[17]: in a study with 52 patients treated with 6 MIU/day IFNβ for 8 wk, the factors predicting efficacy of the treatment were primarily younger age and low pre-treatment viral load, and secondarily, HCV genotype 2a or 2b. The influence of low viral load in the outcome of therapy was further documented in a study in which 112 CHC patients received 6 MIU/d intravenous natural IFNβ for 12 wk[21]. In this trial, 88% of patients presenting a low pre-treatment viral load (< 6.3×105 copies/mL), experienced a virological sustained response, as compared with only 22% patients that had a high viral load (in spite of the latter having the chance to receive an additional administration of IFNβ three times weekly for subsequent 14 wk at the patients’ request).

Recently, Mochizuki et al have studied the effect of “in vitro” IFNβ on HCV in PBMC analysing whether this effect was associated with clinical response to IFNβ[22]. Twenty-seven patients with CHC were enrolled into this study. They were given intravenous administration of 6 MIU IFNβ daily for 6 wk followed by three times weekly for 20 wk. PBMC collected before IFNβ therapy were incubated with IFNβ and HCV-RNA in PMBC was semi-quantitatively determined. Eight patients (32%) had sustained loss of serum HCV-RNA with normal serum ALT levels after IFN therapy. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the decrease of HCV-RNA amount in PBMC by IFNβ was the only independent predictor for complete response (P < 0.05). The authors proposed that the effect of in vitro IFNβ on HCV in PBMC reflects clinical response and would be taken into account as a predictive marker of IFNβ therapy for CHC.

The route of IFNβ administration might also influence the outcome of treatment. Reports can be found in the literature describing intramuscular[12,29,30,32], subcutaneous[28,35,40] and intravenous injections[17,21,22,41-45]. Since there are no trials directly comparing the results of one route vs the other, no clear recommendations exist. The most appropriate route shoud be selected in each case to grant sufficient bioavailability, reduced toxicity, comfortable administration and adequate patient compliance.

A number of studies have evaluated the performance of IFNβvs IFNα in CHC patients[30,32,34,41,42,46,47]. Generally, IFNβ has led to poorer outcomes than IFNα, particularly when IFNβ was administered either through the intramuscular route[31,32] (probably due to low bioavailability or to insufficient dose levels), or with a once-daily regimen[46]. Only one small study reported a similar efficacy of IFNβ and IFNα when both were given subcutaneously, at a dose of 3 MIU, three times weekly for 6 mo[3]. However, the good tolerability of IFNβ in all studies suggests that further trials aimed at improving its clinical efficacy might produce interesting results. Asahina et al investigated the reason underlying the differences in clinical efficacy between both interferons by assessing HCV dynamics in serum and PBMC of patients treated with IFNα (alone or in combination with ribavirin) and IFNβ (twice-a-day or once-a-day administration)[31]. Although improved viral clearance dynamics were observed with combination or twice-daily dosing regimens (leading to increased rates of sustained eradication of HCV), no dramatic effects in the slopes of HCV decline or in HCV half-lives in the second phase were seen between IFNα and IFNβ.

An interesting opportunity for IFNβ is its use as an alternative in patients not responding to IFNα. A randomized study with 200 clinically nonresponding CHC patients analysed the efficacy of intravenous IFNβ, in comparison with combination of IFNα and ribavirin for 12 wk[42]. The short-term treatment outcome showed a biochemical and virological response in 42% of patients treated with IFNβvs 22% in patients treated with combination therapy. Sustained response (as documented after a further 48 wk) was seen in 21% and 13% of patients, respectively. These data indicate that, at least as a short-term therapy, IFNβ may offer a chance for sustained response in a subset of IFNα non-responders.

Cheng et al have evaluated the efficacy of IFNβ-1a in the treatment of CHC patients unresponsive to IFNα in a multicentre, randomized study[48]. A total of 267 patients were randomized to one of four groups: subcutaneous IFNβ-1a 12 MIU (44 μg) or 24 MIU (88 μg) administered 3 times weekly or daily. Patients were treated for 48 wk and then followed up for an additional 24 wk. There was a tendency towards a dose-response relationship regarding virological and biochemical response. Overall, 22 patients (8.3%) had a virological response at the end of treatment; 9 patients (3.4%) had a sustained virological response (SVR). Strikingly, 21.7% (5/23) of Chinese patients achieved SVR. Univariate analysis revealed that race was the only variable related to SVR (odds ratio 16.6; 35% CI 4.1 = 67.3; P < 0.0001). The authors concluded that IFNβ-1a provided considerable clinical benefit in Chinese patients with CHC unresponsive to IFNα.

A few more pilot studies (with cohorts of between 10 and 30 patients) have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of IFNβ in CHC non-responder patients[40,43,44,49]. Although these have confirmed that some patients may benefit from IFNβ therapy in terms of early biochemical and viral responses (between 20% and 40%, depending on the doses and regimens), sustained responses have been very seldom observed. None of the studies has shown a clear advantage for patients infected with any particular HCV genotype. Pellicano et al[40] treated 30 non-responders with 12 MIU subcutaneous IFNβ, three times weekly for 3 mo. Patients responding were given 12 MIU IFNβ for a further 3 mo, and those showing no biochemical and viral improvement had their dose increased to 18 MIU for the same 3 mo. While 20% of patients exhibited a response at the end of treatment, only one patient presented a sustained virological response at the end of post-treatment follow-up. In relapser patients after IFNβ monotherpay, few studies exist. Nomura et al treated 43 relapser patients genotype 1 CHC after IFNβ monotherapy, with 6 MIU of IFNβ, achieving a sustained virological response of 21%. Authors also found that better results were obtained when therpay with IFNβ was given near relpase[50]. In summary, trials with IFNβ monotherapy for CHC patients resistant to IFNα have shown conflicting results. Tolerability was good in most cases, but further investigation on strategies to improve efficacy of the drug are clearly needed.

There is limited information about the efficacy of IFNβ in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of CHC patients. In a pilot study, 27 patients were randomized to receive either 800-1000 mg/d ribavirin or IFNβ alone (3 MIU, three times weekly), or combination of the two for 24 wk[31]. No significant differences in terms of sustained viral response were observed between patients treated with IFNβ monotherapy or in combination with ribavirin (2 of 9 patients, respectively). Tolerability was good in all groups. The limited number of patients included in the study hampers reaching conclusions about the benefits of combination therapy. Pellicano et al[41] randomized 102 naïve CHC patients to receive 6 MIU of recombinant human IFNβ-1a subcutaneously every day for 24 wk alone or in combination with ribavirin (1000 mg/d in patients < 70 kg and 1200 mg/d in patients > 70 kg).The end-of-treatment virological response rate was 29.4% for monotherapy and 41.2% for combination therapy. After an additional 24 wk follow-up period, the sustained virological response rate in both groups was 21.56% and 27.45%, respectively. Tolerability was good, without major differences between groups (except for 2 patients in the combination therapy group who had to stop therapy due to drug-related adverse events). These results suggest an improvement of efficacy by combination therapy with respect to monotherapy. Other associations with IFNβ (amantadine, adelavin-9) do not obtain better results than those reached with ribavirin[36,51,52].

Acute hepatitis C. Several studies and case reports dealing with the efficacy and safety of IFNβ in patients with acute hepatitis C have been published[45,53,54]. Omata et al randomized 25 acute non-A, non-B hepatitis patients to receive or not an average of 52 MIU IFNβ for 30 d, and in those showing elevated serum aminotransferase concentrations after one year, a second course of IFNβ was administrated[53]. Ten out of 11 treated patients showed normalized serum aminotransferase and negative HCV RNA at 3-years follow-up, as compared with 3 out of 14 untreated patients. Tadano and cols. Treated 97 non-A, non-B hepatitis cases with different regimens of IFNβ, reporting a resolution rate of 32% among patients with positive HCV RNA[54]. The dose of 336 MIU produced the highest resolution rate (83%; 10/12 of patients treated with this schedule). Lower doses of IFNβ induced resolution rates of 0% to 38%. These data suggest that IFNβ may prevent the progression of acute non-A, non-B hepatitis to chronically by eradicating HCV.

Cirrhosis. According to the currently available data, IFNβ is not efficacious for the treatment of patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Sixty-one patients were randomized to receive or not 6 MIU IFNβ twice-a-week for 6 mo followed by 3 MIU/tiw for 6 mo, and followed-up for 5 years[33]. End-of-treatment biochemical and virological responses were observed in 13% and 11% of treated patients. At long-term follow-up, 16% of treated and 17% of untreated patients presented normalized serum alanine aminotransferase levels, whereas only 5% and 4% respectively, presented a virological response. Additionally, no significant reduction of cirrhosis-related clinical events (variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, progression to hepatocellular carcinoma), was associated with treatment.

IFNβ for other chronic liver diseases. IFNβ might also represent an appropriate therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients not responding to IFNα. In a pilot study, Muñoz et al treated 29 such patients with 6 MIU IFNβ, five times a week for 24 wk, and followed-up the patients for 48 wk[55]. End-of-treatment biochemical and virological response was obtained in 38% of patients and sustained virological response occurred in 21% of patients. The therapy was well tolerated and safe. The results were particularly positive for patients with HbeAg-negative/HBV DNA-positive chronic hepatitis B.

As already mentioned throughout this review, IFNβ generally presents a good tolerability, even in combination with ribavirin. This constitutes one of the main strengths of this drug as an alternative to other CHC therapies. The fact that IFNβ is the treatment of choice for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, a chronic disease requiring high doses and frequent administration for years, has resulted in the availability of abundant information on this drug's safety. Severe side effects are unfrequent and several clinical studies in CHC patients report no requirement for treatment discontinuation and/or dose modifications. The adverse effects most frequently encountered during IFNβ therapy are flu-like syndrome, fever, fatigue and injection-site reactions. The drug seems to be equally well tolerated by responders and non-responders. The frequency of adverse events is also similar among subpopulations such as patients with genotype-1b HCV hepatitis unresponsive to IFNα treatment or with HCV-related cirrhosis and patients with acute viral hepatitis. The interested reader is referred to a recently published review updating the available information about safety of IFNβ treatment for CHC[56].

HCV infection remains an important health problem. Although the therapeutic options have experienced dramatic improvements during recent years, treatment of the disease is still far from optimal, particularly for those subpopulations that do not respond to the standard combination therapy with IFNα and ribavirin. Although in some cases the use of higher doses or longer treatment periods may be effective, these approaches are generally associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects, which may either lead to a reduction in patient compliance or require drug withdrawal. IFNβ could represent an interesting alternative for treating CHC in these patients. A review of the literature shows controversial data about IFNβ efficacy in CHC, the main reason being that many results stem from pilot studies with small cohorts of patients. However, promising results have been obtained in some subgroups of patients that fail to respond to IFNα. Additionally, the good tolerability of IFNβ represents an important advantage of the drug. The rates of dropouts in controlled clinical trials, as well as the need for dose reductions or treatment discontinuation are very low. All these data suggest that it might be worth assessing the value of IFNβ in randomized studies with larger cohorts patients, with special emphasis on the combination with ribavirin. IFNβ may represent an efficacious and safe second-line therapy for those populations of patients not eligible or not tolerating standard therapy, as well as for non-responders.

S- Editor Guo SY E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | CDC. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-39. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Recommendations from the National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement: management of hepatitis C: 2002. Hepatology. 2002;36:1039. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Medina J, Garcia-Buey L, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, Trapero-Marugan M, Moreno-Otero R. Combined antiviral options for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL Jr, Haussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4747] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pestka S, Langer JA, Zoon KC, Samuel CE. Interferons and their actions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:727-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1333] [Cited by in RCA: 1392] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bocci V. Physicochemical and biologic properties of interferons and their potential uses in drug delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1992;9:91-133. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Alam JJ. Interferon-beta treatment of human disease. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:688-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bertolotto A, Deisenhammer F, Gallo P, Sölberg Sørensen P. Immunogenicity of interferon beta: differences among products. J Neurol. 2004;251 Suppl 2:II15-II24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Munafo A, Trinchard-Lugan I I, Nguyen TX, Buraglio M. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of recombinant human interferon beta-1a after intramuscular and subcutaneous administration. Eur J Neurol. 1998;5:187-193. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kiyosawa K, Sodeyama T, Nakano Y, Yoda H, Tanaka E, Hayata T, Tsuchiya K, Yousuf M, Furuta S. Treatment of chronic non-A non-B hepatitis with human interferon beta: a preliminary study. Antiviral Res. 1989;12:151-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fesce E, Airoldi A, Mondazzi L, Maggi G, Gubertini G, Bernasconi G, Del Poggio P, Bozzetti F, Idéo G. Intramuscular beta interferon for chronic hepatitis C: is it worth trying. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:185-188. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shiratori Y, Perelson AS, Weinberger L, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Nakata R, Ihori M, Hirota K, Ono N, Kuroda H. Different turnover rate of hepatitis C virus clearance by different treatment regimen using interferon-beta. J Hepatol. 2000;33:313-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoshioka K, Yano M, Hirofuji H, Arao M, Kusakabe A, Sameshima Y, Kuriki J, Kurokawa S, Murase K, Ishikawa T. Randomized controlled trial of twice-a-day administration of natural interferon beta for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2000;18:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lindsay KL. Therapy of hepatitis C: overview. Hepatology. 1997;26:71S-77S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kainuma M, Ogata N, Kogure T, Kohta K, Hattori N, Mitsuma T, Terasawa K. The efficacy of a herbal medicine (Mao-to) in combination with intravenous natural interferon-beta for patients with chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1b and high viral load: a pilot study. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fukutomi T, Fukutomi M, Iwao M, Watanabe H, Tanabe Y, Hiroshige K, Kinukawa N, Nakamuta M, Nawata H. Predictors of the efficacy of intravenous natural interferon-beta treatment in chronic hepatitis C. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:692-698. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kurosaki M, Enomoto N, Murakami T, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Yamamoto C, Ikeda T, Tozuka S, Izumi N, Marumo F. Analysis of genotypes and amino acid residues 2209 to 2248 of the NS5A region of hepatitis C virus in relation to the response to interferon-beta therapy. Hepatology. 1997;25:750-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alberti A, Chemello L, Bonetti P, Casarin C, Diodati G, Cavalletto L, Cavalletto D, Frezza M, Donada C, Belussi F. Treatment with interferon(s) of community-acquired chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis type C. The TVVH Study Group. J Hepatol. 1993;17 Suppl 3:S123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kaito M, Yasui-Kawamura N, Iwasa M, Kobayashi Y, Nakagawa N, Fujita N, Ikoma J, Gabazza EC, Watanabe S, Adachi Y. Twice-a-day versus once-a-day interferon-beta therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:775-778. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Shiratori Y, Nakata R, Shimizu N, Katada H, Hisamitsu S, Yasuda E, Matsumura M, Narita T, Kawada K, Omata M. High viral eradication with a daily 12-week natural interferon-beta treatment regimen in chronic hepatitis C patients with low viral load. IFN-beta Research Group. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2414-2421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mochizuki K, Kagawa T, Takashimizu S, Kawazoe K, Kojima S, Nagata N, Nakano A, Nishizaki Y, Shiraishi K, Itakura M. Effect of in vitro interferon-beta administration on hepatitis C virus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a predictive marker of clinical response to interferon treatment for chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:733-736. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kakizaki S, Takagi H, Yamada T, Ichikawa T, Abe T, Sohara N, Kosone T, Kaneko M, Takezawa J, Takayama H. Evaluation of twice-daily administration of interferon-beta for chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Suzuki F, Chayama K, Tsubota A, Akuta N, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K. Twice-daily administration of interferon-beta for chronic hepatitis C is not superior to a once-daily regimen. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:242-247. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Enomoto M, Nishiguchi S, Tanaka M, Fukuda K, Ueda T, Tamori A, Habu D, Takeda T, Shiomi S, Yano Y. Dynamics of hepatitis C virus monitored by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction during first 2 weeks of IFN-beta treatment are predictive of long-term therapeutic response. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:389-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Habersetzer F, Boyer N, Marcellin P, Bailly F, Ahmed SN, Alam J, Benhamou JP, Trepo C. A pilot study of recombinant interferon beta-1a for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Liver. 2000;20:437-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Andrade RJ, Garcia-Escano MD, Valdivielso P, Alcantara R, Sanchez-Chaparro MA, Gonzalez-Santos P. Effects of interferon-beta on plasma lipid and lipoprotein composition and post-heparin lipase activities in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:929-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Castro A, Carballo E, Dominguez A, Diago M, Suarez D, Quiroga JA, Carreno V. Tolerance and efficacy of subcutaneous interferon-beta administered for treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:65-67. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Castro A, Suarez D, Inglada L, Carballo E, Dominguez A, Diago M, Such J, Del Olmo JA, Perez-Mota A, Pedreira J. Multicenter randomized, controlled study of intramuscular administration of interferon-beta for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:27-30. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Villa E, Trande P, Grottola A, Buttafoco P, Rebecchi AM, Stroffolini T, Callea F, Merighi A, Camellini L, Zoboli P. Alpha but not beta interferon is useful in chronic active hepatitis due to hepatitis C virus. A prospective, double-blind, randomized study. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1241-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kakumu S, Yoshioka K, Wakita T, Ishikawa T, Takayanagi M, Higashi Y. A pilot study of ribavirin and interferon beta for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:507-512. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Perez R, Pravia R, Artimez ML, Giganto F, Rodriguez M, Lombrana JL, Rodrigo L. Clinical efficacy of intramuscular human interferon-beta vs interferon-alpha 2b for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 1995;2:103-106. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bernardinello E, Cavalletto L, Chemello L, Mezzocolli I, Donada C, Benvegnú L, Merkel C, Gatta A, Alberti A. Long-term clinical outcome after beta-interferon therapy in cirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C. TVVH Study Group. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:3216-3222. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Frosi A, Sgorbati C, Bestetti B, Lodeville D, Vezzoli S, Vezzoli F. Interferon-α and –β in chronic hepatitis C: efficacy and tolerability. Clin Drug Invest. 1995;9:226-231. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pellicano R, Craxi A, Almasio PL, Valenza M, Venezia G, Alberti A, Boccato S, Demelia L, Sorbello O, Picciotto A. Interferon beta-1a alone or in combination with ribavirin: a randomized trial to compare efficacy and safety in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4484-4489. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Nakamura H, Uyama H, Enomoto H, Kishima Y, Yamamoto M, Yoshida K, Okuda Y, Hirotani T, Kuroda T, Ito H. The combination therapy of interferon and amantadine hydrochloride for patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:222-226. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Nakamura H, Ogawa H, Kuroda T, Yamamoto M, Enomoto H, Kishima Y, Yoshida K, Ito H, Matsuda M, Noguchi S. Interferon treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C infected with high viral load of genotype 2 virus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1373-1376. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Asahina Y, Izumi N, Uchihara M, Noguchi O, Nishimura Y, Inoue K, Ueda K, Tsuchiya K, Hamano K, Itakura J. Interferon-stimulated gene expression and hepatitis C viral dynamics during different interferon regimens. J Hepatol. 2003;39:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fukutomi T, Nakamuta M, Fukutomi M, Iwao M, Watanabe H, Hiroshige K, Tanabe Y, Nawata H. Decline of hepatitis C virus load in serum during the first 24 h after administration of interferon-beta as a predictor of the efficacy of therapy. J Hepatol. 2001;34:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Pellicano R, Palmas F, Cariti G, Tappero G, Boero M, Tabone M, Suriani R, Pontisso P, Pitaro M, Rizzetto M. Re-treatment with interferon-beta of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1377-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Asahina Y, Izumi N, Uchihara M, Noguchi O, Tsuchiya K, Hamano K, Kanazawa N, Itakura J, Miyake S, Sakai T. A potent antiviral effect on hepatitis C viral dynamics in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells during combination therapy with high-dose daily interferon alfa plus ribavirin and intravenous twice-daily treatment with interferon beta. Hepatology. 2001;34:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Barbaro G, Di Lorenzo G, Soldini M, Giancaspro G, Pellicelli A, Grisorio B, Barbarini G. Intravenous recombinant interferon-beta versus interferon-alpha-2b and ribavirin in combination for short-term treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients not responding to interferon-alpha. Multicenter Interferon Beta Italian Group Investigators. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mazzoran L, Grassi G, Giacca M, Gerini U, Baracetti S, Fanni-Canelles M, Zorat F, Pozzato G. Pilot study on the safety and efficacy of intravenous natural beta-interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C unresponsive to alpha-interferon. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29:338-342. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Montalto G, Tripi S, Cartabellotta A, Fulco M, Soresi M, Di Gaetano G, Carroccio A, Levrero M. Intravenous natural beta-interferon in white patients with chronic hepatitis C who are nonresponders to alpha-interferon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:950-953. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Oketani M, Higashi T, Yamasaki N, Shinmyozu K, Osame M, Arima T. Complete response to twice-a-day interferon-beta with standard interferon-alpha therapy in acute hepatitis C after a needle-stick. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Furusyo N, Hayashi J, Ohmiya M, Sawayama Y, Kawakami Y, Ariyama I, Kinukawa N, Kashiwagi S. Differences between interferon-alpha and -beta treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:608-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cheng PN, Marcellin P, Bacon B, Farrell G, Parsons I, Wee T, Chang TT. Racial differences in responses to interferon-beta-1a in chronic hepatitis C unresponsive to interferon-alpha: a better response in Chinese patients. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:418-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Vezzoli M, Girola S, Fossati G, Mazzucchelli I, Gritti D, Mazzone A. [beta-Interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis HCV+, 1b genotype]. Recenti Prog Med. 1998;89:235-240. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Nomura H, Sou S, Nagahama T, Hayashi J, Kashiwagi S, Ishibashi H. Efficacy of early retreatment with interferon beta for relapse in patients with genotype Ib chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2004;28:36-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Uyama H, Enomoto H, Kishima Y, Yamamoto M, Yoshida K, Okuda Y, Hirotani T, Kuroda T, Ito H, Matsuda M. A pilot study of combination therapy with initial high-dose interferon and amantadine hydrochloride for patients with chronic hepatitis C with the genotype 1b virus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2112-2116. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Ebinuma H, Saito H, Tada S, Masuda T, Kamiya T, Nishida J, Yoshioka M, Ishii H. Additive therapeutic effects of the liver extract preparation mixture adelavin-9 on interferon-beta treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1109-1114. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Omata M, Yokosuka O, Takano S, Kato N, Hosoda K, Imazeki F, Tada M, Ito Y, Ohto M. Resolution of acute hepatitis C after therapy with natural beta interferon. Lancet. 1991;338:914-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Takano S, Satomura Y, Omata M. Effects of interferon beta on non-A, non-B acute hepatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled-dose study. Japan Acute Hepatitis Cooperative Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:805-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Munoz R, Castellano G, Fernandez I, Alvarez MV, Manzano ML, Marcos MS, Cuenca B, Solis-Herruzo JA. A pilot study of beta-interferon for treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B who failed to respond to alpha-interferon. J Hepatol. 2002;37:655-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Festi D, Sandri L, Mazzella G, Roda E, Sacco T, Staniscia T, Capodicasa S, Vestito A, Colecchia A. Safety of interferon beta treatment for chronic HCV hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:12-16. [PubMed] |