Published online Apr 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2469

Revised: January 2, 2006

Accepted: January 14, 2006

Published online: April 21, 2006

Diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy is rare and results in a high mortality rate, particularly if early surgical intervention is not undertaken. We report a case in which a woman presenting at 23 wk’s gestation was admitted with symptoms of respiratory failure and bowel obstruction due to incarceration of viscera through a left posterolateral defect of the diaphragm (Bochdalek’s hernia). Surgery (left thoracoabdominal incision) demonstrated compression atelectasis, mediastinal shift, strangulation and gangrene of the herniated viscera which led to segmental resection of the involved portion of large intestine with re-establishment of bowel continuity by end to end anastomosis. The greater omentum was partly necrotic necessitating resection. The diaphragmatic defect was closed with interrupted sutures. Postoperative period was uncomplicated. Pregnancy was allowed to continue until 39 wk’s gestation at which time elective cesarean delivery was performed. It is concluded that symptomatic maternal diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy is a surgical emergency and requires a high index of suspicion.

- Citation: Barbetakis N, Efstathiou A, Vassiliadis M, Xenikakis T, Fessatidis I. Bochdaleck’s hernia complicating pregnancy: Case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(15): 2469-2471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i15/2469.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2469

Diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy is rare and is associated with a poor or complicated outcome, particularly if early surgical intervention is not undertaken[1]. Such hernias usually involve the left diaphragm through a congenital defect or a previous traumatic rupture. The main life-threatening complications described, include respiratory distress, visceral obstruction, strangulation and gangrene of the herniated viscera, visceral perforation (spontaneous or thoracentesis-induced) and maternal death[2-5].

A case of a patient with left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy is described in this report.

A 31-year-old woman in her first pregnancy (23 wk’s gestation) was admitted to our hospital with a 10-day history of dyspnoea, nausea, persistent vomiting and intermittent sharp epigastric and substernal pain leading to a 3 kg weight loss. On physical examination the patient was afebrile, hypotensive with tachycardia (125 beats/min) and dyspnoea (32 breaths/min). There was distention of the neck veins fullness of the supraclavicular fossa. Chest auscultation demonstrated absence of breath sounds in the left hemithorax. Heart sounds were heard to the right of the sternum. Her abdomen was soft and moderately tender over epigastrium and left hypochondrium with audible bowel sounds. Laboratory findings were remarkable only for a white blood count of 13 800/mL (with 88% neutrophils). Electrocardiogram indicated sinus tachycardia and a T-wave flattening. A nasogastric tube was placed and returned 800 mL bilious fluid.

A chest X-ray suggested diaphragmatic hernia because of air bubbles, air-fluid level and non-homogeneous opa-city in the left hemithorax (Figure 1). A right mediastinal shift and loss of the sharp left hemidiaphragm line separating the abdomen from thorax, were also noted.

A chest ultrasound examination demonstrated bowel loops in the left pleural cavity and slight pericardial and pleural effusions and confirmed definitely the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. It is generally considered that the hernia could become manifest on a basis of anatomical weakness possibly evoked by a trauma or increasing abdominal pressure, however, the patient denied any previous trauma.

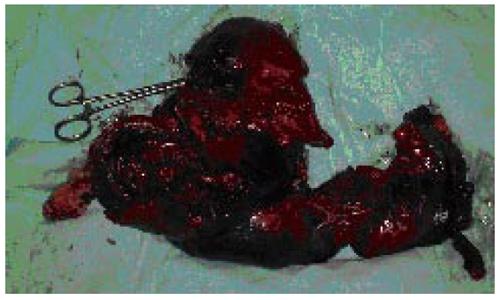

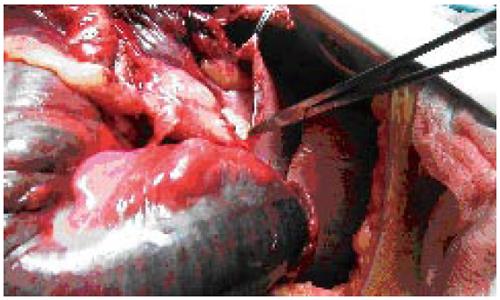

Due to her unstable condition and because of concerns for ischemia of the herniated viscera, the patient was rushed to surgery. On exploration through a left thoracoabdominal incision, a large segment of right and transverse colon, the greater omentum and the stomach were identified in the left hemithorax. Compression atelectasis, mediastinal shift, strangulation and gangrene of large part of the herniated colon were also noted (Figure 2). The viscera had protruded upward through a 4 cm × 7 cm posterolateral foramen of Bochdaleck diaphragmatic defect (Figure 3). The greater omentum seemed to be ischemic. A segmental resection of the involved portion of large intestine with re-establishment of bowel continuity by an end to end anastomosis was mandatory (Figure 4). Stomach was reduced in the abdominal cavity with no evidence of ischemic damage. The diaphragmatic defect was repaired with interrupted sutures. Manipulation of the uterus was avoided during surgery. Fetal well-being was confirmed throughout the procedure by continuous fetal heart rate monitoring.

After surgery, the patient recovered rapidly and her complaints ceased immediately. The postoperative course was uneventful and fetal and uterine activities were monitored daily. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 10 after she tolerated a regular diet.

Pregnancy was allowed to continue until 39 wk’s gestation at which time elective cesarean delivery was performed.

The diaphragm develops during the first 8 wk of gestation. In the eighth week this developing diaphragm leaves two channels located posterolaterally (Bochdaleck) and anteriorly (Morgagni) between the thorax and the abdomen. These two channels are closed by a two-layer membrane derived from pleura and peritoneum. When the posterolateral pleuroperitoneal channels fail to close, these are called foramina of Bochdaleck. Usually, it is rare for a defect like this to remain undetected in childhood through to adult life[6]. When the defect becomes manifest during pregnancy life-threatening events may affect both the mother and fetus. This is due to incarceration or strangulation of intraabdominal structures.

There are various symptoms in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Most of them are due to the effects of abdominal viscera within the pleural cavity and the commonest are chest pain and dyspnoea. Diminished breath sounds on the ipsilateral side are the most common physical finding. There may be signs of high or low mechanical ileus depending on which part of the gastrointestinal tract is herniated. In our patient, intraabdominal viscera herniated into the chest and caused dyspnea due to striking collapse of the left lung. Tachycardia, hypotension and distention of neck veins were the result of mediastinal shift and diminished venous return. Persistent vomitus was a sign of obstruction. However heartburn, nausea, vomiting and malaise are common symptoms during pregnancy. The failure of antacids, antispasmodics and dietary changes to relieve the symptoms especially in women with advanced pregnancy should lead the physician to suspect gastrointestinal pathology[7].

The diagnosis of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy requires a high index of suspicion. As in our case, the key to diagnosis is the chest radiograph. Thoracic ultrasonography, computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging are possible auxilliary diagnostic methods. Pleural effusion or pneumothorax may be mimicked, leading to inappropriate thoracentesis or tube thoracostomy and inadvertent perforation of the herniated viscera[8].

The management of a pregnant patient with symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia is challenging. Traditionally, immediate repair is undertaken if symptoms arise, because further delay might be fatal both to the mother and fetus[5,6] . For asymptomatic patients Kurzel and Naunheim recommended cesarean delivery after fetal lung maturity is documented, with simultaneous hernia repair[6]. They opposed vaginal delivery under any circumstance because of the increased risk of incarceration with subsequent strangulation when the patient is bearing down. They based their recommendation on 17 cases reported in the English literature. In that case series the maternal and fetal morbidity was as high as 55% and 27% respectively, when vaginal delivery was attempted before the diaphragmatic hernia was repaired[6]. Genc et al suggested that gastric decompression might improve the clinical condition of the pregnant patient with a diaphragmatic hernia who presents with symptoms and signs of obstruction[9]. Such an improvement can allow surgery to be delayed until the patient is transferred to a tertiary care center or until antenatal corticosteroids are administered. Given this fact, Genc et al suggested observation and proposed immediate surgery whenever there is any suspicion of visceral incarceration. In our case, symptoms of cardiorespiratory failure and bowel obstruction led us to urgent repair because further delay could be fatal for both mother and fetus. Pregnancy was allowed to continue until 39 wk’s gestation at which time elective cesarean delivery was performed.

The incidence of asymptomatic Bochdaleck's hernia in the adult population was reported to be at least 0.17%, with a female-to-male ratio of 17:5[10]. Despite such a high incidence, the number of pregnancies complicated by unrecognized congenital diaphragmatic hernia is extremely small - 35 cases, including this one, have been reported since 1928[5,9].

In conclusion, the diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy requires a high index of suspicion. Symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and dyspnoea should be investigated adequately. Signs of bowel obstruction and respiratory compromise are indications for a surgical emergency.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Stephenson BM, Stamatakis JD. Late recurrence of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:110-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hill R, Heller MB. Diaphragmatic rupture complicating labor. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:522-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Watkin DS, Hughes S, Thompson MH. Herniation of colon through the right diaphragm complicating the puerperium. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3:583-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fardy HJ. Vomiting in late pregnancy due to diaphragmatic hernia. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:390-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kaloo PD, Studd R, Child A. Postpartum diagnosis of a maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:461-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kurzel RB, Naunheim KS, Schwartz RA. Repair of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:869-871. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gimovsky ML, Schifrin BS. Incarcerated foramen of Bochdalek hernia during pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:156-158. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lacayo L, Taveras JM 3rd, Sosa N, Ratzan KR. Tension fecal pneumothorax in a postpartum patient. Chest. 1993;103:950-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Genc MR, Clancy TE, Ferzoco SJ, Norwitz E. Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1194-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek's hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |