Published online Apr 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2423

Revised: December 22, 2005

Accepted: January 14, 2006

Published online: April 21, 2006

AIM: To describe a simple one-step method involving percutaneous transhepatic insertion of an expandable metal stent (EMS) used in the treatment of obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable malignancies.

METHODS: Fourteen patients diagnosed with obstructive jaundice due to unresectable malignancies were included in the study. The malignancies in these patients were a result of very advanced carcinoma or old age. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography was performed under ultrasonographic guidance. After a catheter with an inner metallic guide was advanced into the duodenum, an EMS was placed in the common bile duct, between a point 1 cm beyond the papilla of Vater and the entrance to the hepatic hilum. In cases where it was difficult to span the distance using just a single EMS, an additional stent was positioned. A drainage catheter was left in place to act as a hemostat. The catheter was removed after resolution of cholestasis and stent patency was confirmed 2 or 3 d post-procedure.

RESULTS: One-step insertion of the EMS was achieved in all patients with a procedure mean time of 24.4 min. Out of the patients who required 2 EMS, 4 needed a procedure time exceeding 30 min. The mean time for removal of the catheter post-procedure was 2.3 d. All patients died of malignancy with a mean follow-up time of 7.8 mo. No stent-related complication or stent obstruction was encountered.

CONCLUSIONS: One-step percutaneous transhepatic insertion of EMS is a simple procedure for resolving biliary obstruction and can effectively improve the patient’s quality of life.

- Citation: Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Shimizu T, Yokomuro S, Aimoto T, Nakamura Y, Uchida E, Arima Y, Watanabe M, Uchida E, Tajiri T. One-step palliative treatment method for obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable malignancies by percutaneous transhepatic insertion of an expandable metallic stent. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(15): 2423-2426

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i15/2423.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2423

The incidence of biliary obstruction resulting from malignancies is increasing. As operative techniques and diagnostic imaging have advanced, more and more patients undergo resection. However, in cases where operation is not possible, prognosis remains poor often because of the presence of obstructive jaundice.

Palliative treatment with a biliary stent is carried out in patients with inoperable malignancies in order to relieve symptoms related to obstructive jaundice, prevent cholangitis and prolong survival. In addition, the biliary insertion procedure only requires a short time of hospitalization, which is especially important for patients with unresectable malignancies because of their poor prognosis.

When first introduced, stent insertion is performed using polyethylene endoprosthese. However, the expandable metallic stent (EMS) has also been available for a number of years [1,2]. EMSs have advantages over plastic stents in that they can be introduced through a smaller delivery catheter, have a larger inner diameter and remain fixed in position after release [3-6].

It was previously reported that one-step method of percutaneous transhepatic insertion of EMSs can be used for obstructive jaundice due to unresectable common bile duct carcinoma[7], further supporting the one-step method of percutaneous transhepatic insertion of EMS to treat obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable malignancies.

This study comprised 14 patients with obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable malignancies, who were admitted into Nippon Medical School or Uchida Hospital from 2002 to 2004. Of the 14 patients (6 men and 8 women), 1 suffered from gastric carcinoma, 3 from recurrence of gastric carcinoma, 4 from pancreas carcinoma, 3 from bile duct carcinoma, 1 from gall bladder carcinoma, and 2 from recurrence of gall bladder carcinoma. The age distribution of the patients ranged between 65-90 years, with a mean age of 77.1 years.

The diagnosis was confirmed by ultrasonography and computed tomography. All patients were diagnosed before cholangiography as having obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable malignancies as a result of very advanced carcinoma or old age.

This study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their families.

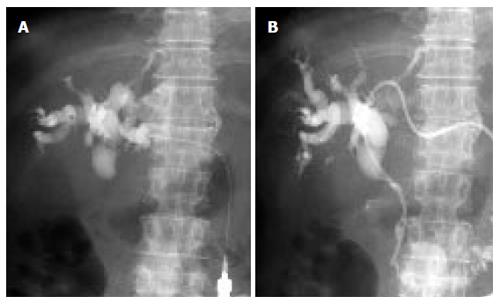

The procedure was performed single-handedly (Hiroshi Yoshida). The portion of the procedure was consistent for all the patients. Following pre-medication with an intravenous injection of pentazocine (15 mg) and hydroxyzine (25 mg), the patient was given a local anesthetic consisting of 1% xylocaine. The appropriate intrahepatic bile duct of the lateral segment or right lobe of the liver was punctured with a sheath needle (19 gauge × 150 mm; Hakko, Tokyo, Japan) under ultrasonographic guidance. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography was then performed (Figure 1A).

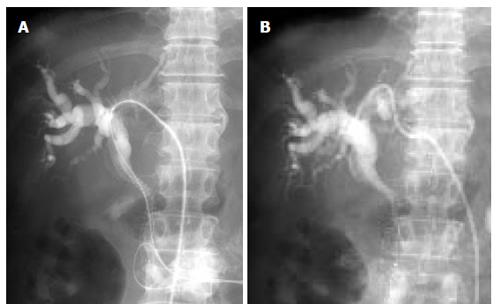

The bile duct obstruction was cleared using a guide wire (RADIFOCUS GUIDE WIRE M, 0.035 inch × 150 cm; TERUMO, Tokyo, Japan). After a catheter with an inner metallic guide (EV drainage catheter, 17 gauge× 270 mm; Hakko, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced into the duodenum, a contrast material was injected to determine the overall length of stenosis (Figure 1B). The guide wire was reinserted and the EV drainage catheter was substituted with an EMS (SMART stent, 10 mm in diameter × 80 mm long; Cordis Endovascular, Warren, NJ) system. In cases where it was difficult to advance the EMS system into the duodenum, a dilatation catheter (PTCS catheter, 9 Fr × 60 cm; Sumitomo Bakelite, Akita, Japan) was inserted prior to insertion of the EMS system. The EMS was then placed in the common bile duct between a point 1 cm beyond the papilla of Vater and the entrance to the hepatic hilum, irrespective of the size of stenotic lesion present (Figure 2A). Where it was difficult to span the distance between the above points with a single EMS, an additional EMS SMART stent (10 mm in diameter × 60 mm long) was inserted connecting lengthways to the first stent. The EV drainage catheter or PTCS catheter was left in place to act as a hemostat at the site of insertion to the liver (Figure 2B). The patient received antibiotics following the stent insertion procedure. As an additional measure, saline was injected daily into the catheter to flush out the bile duct. The catheter was removed after resolution of cholestasis and stent patency was confirmed 2 or 3 d post-procedure.

One-step insertion of the EMS was achieved in all patients. The procedure time ranged between 15-42 min with a mean time of 24.4 min. A single EMS was required in 7 patients, while two EMSs were needed in the other 7. In 2 patients, a PTCS catheter was used because of prior difficulty in inserting the EMS system. Out of the patients who required 2 EMSs, 4 of these needed a procedure time exceeding 30 min.

After successful insertion of the stent, cholestasis rapidly resolved itself in all the patients. The catheter was removed after a mean post-procedure time of 2.3 d. All patients died of malignancy with a mean follow-up time of 7.8 mo. No stent-related complication or stent obstruction was encountered (Table 1).

| Patient No. | Age | Sex | Disease | Procedure time (min) | No.of EMS | Days2 | Outcome |

| 1 | 90 | F | Bile duct ca. | 32 | 21 | 3 | death after 8 mo |

| 2 | 72 | F | Bile duct ca. | 35 | 21 | 2 | death after 5 mo |

| 3 | 87 | F | Bile duct ca. | 20 | 2 | 3 | death after 7 mo |

| 4 | 72 | M | Gastric ca. | 31 | 2 | 2 | death after 5 mo |

| 5 | 67 | M | Recurrence of gastric ca. | 16 | 1 | 2 | death after 4 mo |

| 6 | 66 | F | Recurrence of gastric ca. | 15 | 1 | 2 | death after 12 mo |

| 7 | 90 | F | Recurrence of gastric ca. | 21 | 2 | 3 | death after 10 mo |

| 8 | 72 | M | GB ca. | 42 | 2 | 2 | death after 3 mo |

| 9 | 84 | F | Recurrence of GB ca. | 20 | 1 | 3 | death after 17 mo |

| 10 | 65 | F | Recurrence of GB ca. | 28 | 1 | 2 | death after 11 mo |

| 11 | 82 | M | Pancreas ca. | 20 | 1 | 2 | death after 8 mo |

| 12 | 76 | M | Pancreas ca. | 18 | 1 | 2 | death after 5 mo |

| 13 | 72 | M | Pancreas ca. | 22 | 1 | 2 | death after 6 mo |

| 14 | 84 | F | Pancreas ca. | 22 | 2 | 2 | death after 6 mo |

| Mean | 77.1 | 24.4 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 7.8 |

Long-term survival is poor in patients with malignant bile duct obstruction and in those who are not candidates for surgical resection. The objective of palliation with a biliary stent is to relieve symptoms related to obstructive jaundice, prevent cholangitis and prolong survival. Stenting has also been shown to improve patient quality of life[8].

Since the development of suitable metallic stents, a debate has arisen regarding when to use a metallic stent in preference to a plastic one. Randomized studies comparing metallic and plastic endoprostheses demonstrated that the metallic stent is associated with a lower incidence of complications, remains patent longer and is more cost-effective, although it is initially more expensive[5,6,9-11].

Complications arising from metal stent placement for malignant bile duct obstruction, including tumor ingrowth or overgrowth[4,12], viscus perforation [13,14], fracture[15], and stent migration[16] have been reported. The early occlusion rate ranges between 7%-42% and the late occlusion rate ranges between 12%-38%, with a mean time to stent failure of 6-9 mo[5,6,10,11,17] . In this study, no EMS-related complication or obstruction was encountered. A possible reason is that all the patients suffered from very advanced carcinoma and could not undergo surgery before cholangiography. Therefore, the prognosis of the patients was poor and patients died due to malignancy after just 7.8 mo. A further possible reason is that the EMS was placed in the common bile duct between a point 1 cm beyond the papilla of Vater and the hepatic hilum, irrespective of the size of stenotic lesion, therefore the stenosis was not completely covered to avoid overgrowth. In addition, saline was injected into the catheter on a daily basis to flush out the bile duct and stent.

In this study, percutaneous transhepatic insertion of the EMS was conducted. A different approach is to insert the EMS endoscopically. Recently, it was reported that the EMS can be inserted from the papilla of Vater under endoscope[18-20]. The success rate is below 100% and the time of procedure is relatively long[18-21]. This is because dilation of the stenotic lesion and control of a long EMS system are difficult in this approach. For high-risk patients with very advanced carcinoma or old age, it is imperative to keep operative procedures as straightforward and short as possible. In the endoscopic approach, the lengthy time of procedure is too invasive to be carried out on high-risk patients. With the percutaneous transhepatic insertion in this study, the distribution of the procedure time ranged between 15 - 42 min, with a mean time of 24.4 min. The EMS insertion could be performed single-handedly, easily, and quickly.

A disadvantage of the percutaneous transhepatic approach is that the catheter must be left in place to act as a hemostat at the insertion site of the liver. However, this is also a benefit as the catheter could then be used to confirm the stent patency and to flush the EMS free from coagula or debris for 2 or 3 d post-procedure.

In conclusion, the one-step percutaneous transhepatic insertion of EMS is a simple procedure for resolving biliary obstruction and can effectively improve the patient’s

quality of life.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Neuhaus H, Hagenmüller F, Griebel M, Classen M. Percutaneous cholangioscopic or transpapillary insertion of self-expanding biliary metal stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huibregtse K, Cheng J, Coene PP, Fockens P, Tytgat GN. Endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for biliary strictures--a preliminary report on experience with 33 patients. Endoscopy. 1989;21:280-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rossi P, Bezzi M, Rossi M, Adam A, Chetty N, Roddie ME, Iacari V, Cwikiel W, Zollikofer CL, Antonucci F. Metallic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: results of a multicenter European study of 240 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1994;5:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stoker J, Laméris JS. Complications of percutaneously inserted biliary Wallstents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4:767-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Knyrim K, Wagner HJ, Pausch J, Vakil N. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of metal stents for malignant obstruction of the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1993;25:207-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee MJ, Dawson SL, Mueller PR, Krebs TL, Saini S, Hahn PF. Palliation of malignant bile duct obstruction with metallic biliary endoprostheses: technique, results, and complications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1992;3:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshida H, Tajiri T, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Kawano Y, Mizuguchi Y, Yokomuro S, Uchida E, Arima Y, Akimaru K. One-step insertion of an expandable metallic stent for unresectable common bile duct carcinoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2003;70:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Luman W, Cull A, Palmer KR. Quality of life in patients stented for malignant biliary obstructions. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:481-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wagner HJ, Knyrim K, Vakil N, Klose KJ. Plastic endoprostheses versus metal stents in the palliative treatment of malignant hilar biliary obstruction. A prospective and randomized trial. Endoscopy. 1993;25:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340:1488-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 753] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | O'Brien S, Hatfield AR, Craig PI, Williams SP. A three year follow up of self expanding metal stents in the endoscopic palliation of longterm survivors with malignant biliary obstruction. Gut. 1995;36:618-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Becker CD, Glättli A, Maibach R, Baer HU. Percutaneous palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice with the Wallstent endoprosthesis: follow-up and reintervention in patients with hilar and non-hilar obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schaafsma RJ, Spoelstra P, Pakan J, Huibregtse K. Sigmoid perforation: a rare complication of a migrated biliary endoprosthesis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Marsman JW, Hoedemaker HP. Necrotizing fasciitis: fatal complication of migrated biliary stent. Australas Radiol. 1996;40:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yoshida H, Tajiri T, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Kawano Y, Mizuguchi Y, Arima Y, Uchida E, Misawa H. Fracture of a biliary expandable metallic stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:655-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pescatore P, Meier-Willersen HJ, Manegold BC. A severe complication of the new self-expanding spiral nitinol biliary stent. Endoscopy. 1997;29:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stoker J, Laméris JS, van Blankenstein M. Percutaneous metallic self-expandable endoprostheses in malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wayman J, Mansfield JC, Matthewson K, Richardson DL, Griffin SM. Combined percutaneous and endoscopic procedures for bile duct obstruction: simultaneous and delayed techniques compared. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:915-918. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Besser P. Percutaneous treatment of malignant bile duct strictures in patients treated unsuccessfully with ERCP. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7 Suppl 1:120-122. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tibble JA, Cairns SR. Role of endoscopic endoprostheses in proximal malignant biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Swaroop VS, Dhir V, Mohandas KM, Wagle SD, Vazifdar KF, Gopalakrishnan G, Sharma OP, Jagannath P, Desouza LJ. Endoscopic palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice using resterilized accessories: an audit of success, complications, mortality and cost. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1997;16:91-93. [PubMed] |