Published online Jan 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.154

Revised: June 8, 2005

Accepted: June 9, 2005

Published online: January 7, 2006

Acute abdominal pain with signs and symptoms of peritonitis due to sudden extravasation of chyle into the peritoneal cavity is a rare condition that is often mistaken for other disease processes. The diagnosis is rarely suspected preoperatively. We report a case of spontaneous chylous peritonitis that presented with typical symptoms of acute appendicitis such as intermittent fever and epigastric pain radiating to the lower right abdominal quadrant before admission.

- Citation: Fang FC, Hsu SD, Chen CW, Chen TW. Spontaneous chylous peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(1): 154-156

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i1/154.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.154

Chylous ascites is the accumulation of a milky or creamy peritoneal fluid rich in triglycerides due to the presence of lymph. It is a rare clinical condition that results from the disruption of the abdominal lymphatic system. Multiple causes have been described including abdominal malignancy, cirrhosis, inflammation, congenital and postoperative or traumatic causes, and miscellaneous disorders. Management is based on identifying and treating the underlying cause. A sudden outpouring of chyle into the peritoneal cavity may produce acute chylous peritonitis. Patients with such defect usually present with the features of acute abdomen. Very few cases of acute chylous peritonitis have been described in the literature. We have discussed the clinical features and management of acute chylous peritonitis, and its rarity and presentation compared to common surgical emergencies, such as acute appendicitis.

A 22-year-old male presented with intermittent fever and abdominal pain for two days before admission. He first presented at a clinic, where acute appendicitis was suspected. He was referred by the clinic to our hospital for further management. The symptoms of abdominal distension and pain were continuous and aggravated by any movement. The patient did not have any history of previous trauma or similar pain, and there was nothing relevant in his past medical history. He did not smoke cigarettes or consume alcohol, and denied any recent long distance or overseas travel. On examination, his temperature was 38.2 ºC, pulse rate was 80/min, and blood pressure was 116/70 mmHg. The systemic examination was unremarkable. The abdomen was soft and ovoid in shape, and there was tenderness over the periumbilical and right lower quadrant regions. Bowel sounds were audible. Blood analysis gave the following values: total leukocyte count, 11.6×109/µL; Hb, 143 g/L; platelet count, 31.4×109/µL; neutrophils, 64.3%; lymphocytes, 22.7%; Na, 141 mmol/L; K, 3.9 mmol/L; urea, 3.9mmol/L; creatinine, 70.7µmol/L; glucose, 5.3mmol/L; AST, 367nkat/L; and ALT, 133nkat/L.

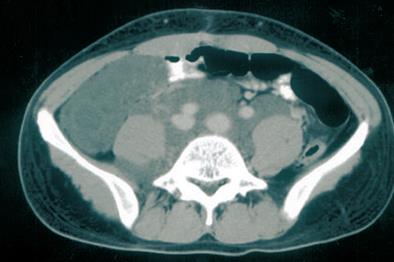

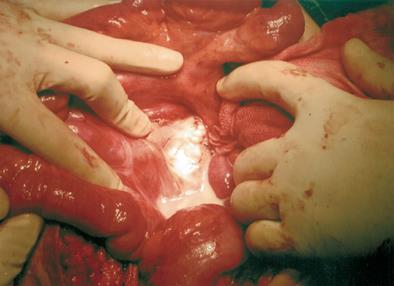

The chest X-ray was normal, but the abdominal X-ray showed nonspecific gas-filled loops of the large intestine. Computed tomography of the abdomen with contrast showed lobulated fluid accumulation over the retroperitoneal space extending from the level of the renal hilum into the right side pelvis and right inguinal area (Figure 1). Suspecting a ruptured appendix, we performed an exploratory laparotomy. When entering the peritoneum, we noted a large amount of milky fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Chylous ascites was first considered because of the obvious lymphatic leakage from the thoracic duct after we opened the retroperitoneum (Figure 2). We performed suture ligation of the lymphatic leakage and drainage of the retroperitoneal lymphocele. Postoperative drainage was < 100 mL in the first week. The patient commenced a low-fat diet, and was recovering well after a 6-month follow-up.

Ascites is the presence of excess fluid in the peritoneal cavity and is a common clinical finding with a wide range of causes, which can require varied treatment. Acute chylous peritonitis is defined as an acute abdomen with all the signs of acute peritoneal irritation resulting from free chyle in the peritoneal cavity, without any underlying disease. Acute chylous peritonitis can also involve extravasation of milky or creamy peritoneal fluid that is rich in triglycerides with small amounts of cholesterol and phospholipids, caused by the presence of thoracic or intestinal lymph in the abdominal cavity. Chylous ascites occurs in one in 20 000 patients admitted to the hospital[1].

The lymphatic system is an accessory route through which fluids and protein flow from the interstitial spaces to the vascular system. Almost all tissues of the body have lymphatic channels composed of one-way valves that drain the excess fluid from the interstitial spaces of tissue. These channels play a pivotal role in clearing the interstitium of debris and bacteria, which are carried to lymph nodes where they are opsonized and phagocytized. Gastrointestinal tract lymphatics also transport absorbed water and lipids to the circulatory system[2]. In the gut, long chain triglycerides are converted into monoglycerides, free fatty acids, and absorbable chylomicrons, which explain the high content of triglycerides and the milky, cloudy appearance of lymph. In our case, the triglyceride concentration in the ascites fluid was 5.48 mmol/L, much higher than the blood triglyceride concentration of 102 mg/dL. The basal flow rate of lymphatic fluid through the thoracic duct averages about 1.0 mL/kg per an hour, with a total volume of 1 500 - 1 700 mL/d. These volumes increase markedly with the ingestion of fats, and fluid rates as high as 200 mL/h have been reported[3].

Chylous ascites may result from many pathological conditions, including congenital defects of the lymphatic system; nonspecific bacterial, parasitic, and tuberculous peritoneal infections; liver cirrhosis; malignant neoplasm; and blunt abdominal trauma. These etiologies may be categorized into distinct mechanism-based groups[4]. The most common etiological factors are abdominal malignancy and congenital lymphatic abnormalities in adults and children, respectively[5]. We have presented an unusual case of spontaneous chylous ascites-related peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis in a young adult. Abdominal surgery is another common cause that is most frequently associated with the resection of an abdominal aortic aneurysm or retroperitoneal lymph node dissection[6]. Various vascular surgical procedures such as aorta-to-femoral artery bypass may cause chylous complications[7]. It has been suggested that overloading of the lymphatic channels with chyle after a heavy fatty meal may cause extravasation of chyle intraperitoneally and retroperitoneally[8].

Abdominal distension is the most common symptom in patients with chylous ascites. Other clinical features include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, edema, weakness, nausea, dyspnea, weight gain, lymphadenopathy, early satiety, fever, and night sweats. The clinical presentation of acute abdomen is less common. Free chyle is relatively nonirritating to the serosal surface, but pain may result from the stretching of the retroperitoneum and the mesenteric serosa[8]. The pain is severe and a physical examination may lead to the misdiagnosis of appendicitis, cholecystitis, mesenteric arterial embolism, or a perforated viscus. The unusual case we present here is spontaneous chylous ascites-related peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis in a young adult. Just like a similar case reported by Lamblim et al [9] the diagnosis was established by the celiotomy.

The diagnosis of chylous ascites is confirmed by analyzing the ascites fluid, which is only possible if such a diagnosis is suspected preoperatively. The chief characteristics of chylous effusions include a milky appearance, separation into a creamy layer on standing, lacking an odor, alkaline chemical properties, specific gravity greater than 1.012, bacteriostatic properties, 3% total protein, staining of fat globules with Sudan red stain, fat content of 0.4% - 4%, and total solids > 4%[10]. The triglyceride level is an important diagnostic tool, and concentration in the chylous ascites is typically two to eight times that of plasma[11]. True chylous ascites must be distinguished from “chyliform” and “pseudochylous” effusions, in which the turbid appearance is due to cellular degeneration from bacterial peritonitis or neoplasm. However, the triglyceride concentration is low in these effusions. Other diagnostic tests such as computed tomography, lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, and laparotomy have the highest yield of diagnostic information[4].

The optimal management of true chylous peritonitis depends upon the underlying etiology. In patients with symptoms of an acute abdominal process, immediate exploration should be performed. Laparotomy usually allows a definitive diagnosis and provides an opportunity to address the underlying cause. The source of chylous extravasation can be corrected by ligation of the leaking lymphatics or removal of the offending lesion, the cause of many congenital and all traumatic cases. The goals of nonsurgical therapy for chylous ascites include maintaining or improving nutrition, and decreasing the rate of chyle formation. Dietary intervention involves a diet that is rich in protein, and low in fat and medium-chain triglycerides to decrease lymph flow in the major lymphatic tracts and to facilitate the closure of chylous fistulas[12]. Total parenteral nutrition can be used to achieve complete bowel rest and might allow resolution of the chylous ascites. Somatostatin improves chylous ascites by inhibiting lymph fluid excretion through specific receptors found in the normal intestinal wall of lymphatic vessels[13]. In patients with a large amount of ascites, a total paracentesis to relieve discomfort and dyspnea can be performed and repeated as needed. However, one should note the risk of infection and fat emboli. If the patients are poor surgical candidates and refractory to nonsurgical treatment, peritoneovenous shunting may be an option, although these shunts carry a high rate of complications[14].

In conclusion, we have described a rare case of acute chylous peritonitis that mimicked acute appendicitis, but could not identify the cause. This case suggests that diagnostic laparoscopy may play an important role in the initial management of this condition[15].

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wu M

| 1. | Press OW, Press NO, Kaufman SD. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:358-364. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Aalami OO, Allen DB, Organ CH. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000;128:761-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Madding GF, McLaughlin RF, McLaughlin RF. Acute chylous peritonitis. Ann Surg. 1958;147:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896-1900. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Browse NL, Wilson NM, Russo F, al-Hassan H, Allen DR. Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Combe J, Buniet JM, Douge C, Bernard Y, Camelot G. [Chylothorax and chylous ascites following surgery of an inflammatory aortic aneurysm. Case report with review of the literature]. J Mal Vasc. 1992;17:151-156. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pabst TS, McIntyre KE, Schilling JD, Hunter GC, Bernhard VM. Management of chyloperitoneum after abdominal aortic surgery. Am J Surg. 1993;166:194-18; discussion 194-18;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Weichert RF, Jamieson CW. Acute chylous peritonitis. A case report. Br J Surg. 1970;57:230-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lamblin A, Mulliez E, Lemaitre L, Pattou F, Proye C. [Acute peritonitis: a rare presentation of chylous ascites]. Ann Chir. 2003;128:49-52. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hibbeln JF, Wehmueller MD, Wilbur AC. Chylous ascites: CT and ultrasound appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:138-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ward PC. Interpretation of ascitic fluid data. Postgrad Med. 1982;71:171-13, 171-13. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hashim SA, Roholt HB, Babayan VK, Vanitallie TB. Treatment of chyluria and chylothorax with medium chain triglyceride. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:756-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shapiro AM, Bain VG, Sigalet DL, Kneteman NM. Rapid resolution of chylous ascites after liver transplantation using somatostatin analog and total parenteral nutrition. Transplantation. 1996;61:1410-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Voros D, Hadziyannis S. Successful management of postoperative chylous ascites with a peritoneojugular shunt. J Hepatol. 1995;22:380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sanna A, Adani GL, Anania G, Donini A. The role of laparoscopy in patients with suspected peritonitis: experience of a single institution. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13:17-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |